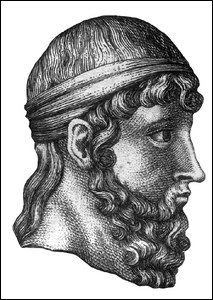

Plato: Phaedo

The Phaedo is one of the most widely read dialogues written by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It claims to recount the events and conversations that occurred on the day that Plato’s teacher, Socrates (469-399 B.C.E.), was put to death by the state of Athens. It is the final episode in the series of dialogues recounting Socrates’ trial and death. The earlier Euthyphro dialogue portrayed Socrates in discussion outside the court where he was to be prosecuted on charges of impiety and corrupting the youth; the Apology described his defense before the Athenian jury; and the Crito described a conversation during his subsequent imprisonment. The Phaedo now brings things to a close by describing the moments in the prison cell leading up to Socrates’ death from poisoning by use of hemlock.

The Phaedo is one of the most widely read dialogues written by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It claims to recount the events and conversations that occurred on the day that Plato’s teacher, Socrates (469-399 B.C.E.), was put to death by the state of Athens. It is the final episode in the series of dialogues recounting Socrates’ trial and death. The earlier Euthyphro dialogue portrayed Socrates in discussion outside the court where he was to be prosecuted on charges of impiety and corrupting the youth; the Apology described his defense before the Athenian jury; and the Crito described a conversation during his subsequent imprisonment. The Phaedo now brings things to a close by describing the moments in the prison cell leading up to Socrates’ death from poisoning by use of hemlock.

Among these “trial and death” dialogues, the Phaedo is unique in that it presents Plato’s own metaphysical, psychological, and epistemological views; thus it belongs to Plato’s middle period rather than with his earlier works detailing Socrates’ conversations regarding ethics. Known to ancient commentators by the title On the Soul, the dialogue presents no less than four arguments for the soul’s immortality. It also contains discussions of Plato’s doctrine of knowledge as recollection, his account of the soul’s relationship to the body, and his views about causality and scientific explanation. Most importantly of all, Plato sets forth his most distinctive philosophical theory—the theory of Forms—for what is arguably the first time. So, the Phaedo merges Plato’s own philosophical worldview with an enduring portrait of Socrates in the hours leading up to his death.

Table of Contents

- The Place of the Phaedo within Plato’s works

- Drama and Doctrine

- Outline of the Dialogue

- References and Further Reading

1. The Place of the Phaedo within Plato’s works

Plato wrote approximately thirty dialogues. The Phaedo is usually placed at the beginning of his “middle” period, which contains his own distinctive views about the nature of knowledge, reality, and the soul, as well as the implications of these views for human ethical and political life. Its middle-period classification puts it after “early” dialogues such as the Apology, Euthyphro, Crito, Protagoras, and others which present Socrates’ search—usually inconclusive—for ethical definitions, and before “late” dialogues like the Parmenides, Theaetetus, Sophist, and Statesman. Within the middle dialogues, it is uncontroversial that the Phaedo was written before the Republic, and most scholars think it belongs before the Symposium as well. Thus, in addition to being an account of what Socrates said and did on the day he died, the Phaedo contains what is probably Plato’s first overall statement of his own philosophy. His most famous theory, the theory of Forms, is presented in four different places in the dialogue.

2. Drama and Doctrine

In addition to its central role in conveying Plato’s philosophy, the Phaedo is widely agreed to be a masterpiece of ancient Greek literature. Besides philosophical argumentation, it contains a narrative framing device that resembles the chorus in Greek tragedy, references to the Greek myth of Theseus and the fables of Aesop, Plato’s own original myth about the afterlife, and in its opening and closing pages, a moving portrait of Socrates in the hours leading up to his death. Plato draws attention (at 59b) to the fact that he himself was not present during the events retold, suggesting that he wants the dialogue to be seen as work of fiction.

Contemporary commentators have struggled to put together the dialogue’s dramatic components with its lengthy sections of philosophical argumentation—most importantly, with the four arguments for the soul’s immortality, which tend to strike even Plato’s charitable interpreters as being in need of further defense. (Socrates himself challenges his listeners to provide such defense at 84c-d.) How seriously does Plato take these arguments, and what does the surrounding context contribute to our understanding of them? While this article will concentrate on the philosophical aspects of the Phaedo, readers are advised to pay close attention to the interwoven dramatic features as well.

3. Outline of the Dialogue

The dialogue revolves around the topic of death and immortality: how the philosopher is supposed to relate to death, and what we can expect to happen to our souls after we die. The text can be divided, rather unevenly, into five sections:

(1) an initial discussion of the philosopher and death (59c-69e)

(2) three arguments for the soul’s immortality (69e-84b)

(3) some objections to these arguments from Socrates’ interlocutors and his response, which includes a fourth argument (84c-107b)

(4) a myth about the afterlife (107c-115a)

(5) a description of the final moments of Socrates’ life (115a-118a)

The dialogue commences with a conversation (57a-59c) between two characters, Echecrates and Phaedo, occurring sometime after Socrates’ death in the Greek city of Phlius. The former asks the latter, who was present on that day, to recount what took place. Phaedo begins by explaining why some time had elapsed between Socrates’ trial and his execution: the Athenians had sent their annual religious mission to Delos the day before the trial, and executions are forbidden until the mission returns. He also lists the friends who were present and describes their mood as “an unaccustomed mixture of pleasure and pain,” since Socrates appeared happy and without fear but his friends knew that he was going to die. He agrees to tell the whole story from the beginning; within this story the main interlocutors are Socrates, Simmias, and Cebes. Some commentators on the dialogue have taken the latter two characters to be followers of the philosopher Pythagoras (570-490 B.C).

a. The Philosopher and Death (59c-69e)

Socrates’ friends learn that he will die on the present day, since the mission from Delos has returned. They go in to the prison to find Socrates with his wife Xanthippe and their baby, who are then sent away. Socrates, rubbing the place on his leg where his just removed bonds had been, remarks on how strange it is that a man cannot have both pleasure and pain at the same time, yet when he pursues and catches one, he is sure to meet with the other as well. Cebes asks Socrates about the poetry he is said to have begun writing, since Evenus (a Sophist teacher, not present) was wondering about this. Socrates relates how certain dreams have caused him to do so, and says that he is presently putting Aesop’s fables into verse. He then asks Cebes to convey to Evenus his farewell, and to tell him that—even though it would be wrong to take his own life—he, like any philosopher, should be prepared to follow Socrates to his death.

Here the conversation turns toward an examination of the philosopher’s attitude toward death. The discussion starts with the question of suicide. If philosophers are so willing to die, asks Cebes, why is it wrong for them to kill themselves? Socrates’ initial answer is that the gods are our guardians, and that they will be angry if one of their possessions kills itself without permission. As Cebes and Simmias immediately point out, however, this appears to contradict his earlier claim that the philosopher should be willing to die: for what truly wise man would want to leave the service of the best of all masters, the gods?

In reply to their objection, Socrates offers to “make a defense” of his view, as if he were in court, and submits that he hopes this defense will be more convincing to them than it was to the jury. (He is referring here, of course, to his defense at his trial, which is recounted in Plato’s Apology.) The thesis to be supported is a generalized version of his earlier advice to Evenus: that “the one aim of those who practice philosophy in the proper manner is to practice for dying and death” (64a3-4).

Socrates begins his defense of this thesis, which takes up the remainder of the present section, by defining death as the separation of body and soul. This definition goes unchallenged by his interlocutors, as does its dualistic assumption that body and soul are two distinct entities. (The Greek word psuchē is only roughly approximate to our word “soul”; the Greeks thought of psuchē as what makes something alive, and Aristotle talks about non-human animals and even plants as having souls in this sense.) Granted that death is a soul/body separation, Socrates sets forth a number of reasons why philosophers are prepared for such an event. First, the true philosopher despises bodily pleasures such as food, drink, and sex, so he more than anyone else wants to free himself from his body (64d-65a). Additionally, since the bodily senses are inaccurate and deceptive, the philosopher’s search for knowledge is most successful when the soul is “most by itself.”

The latter point holds especially for the objects of philosophical knowledge that Plato later on in the dialogue (103e) refers to as “Forms.” Here Forms are mentioned for what is perhaps the first time in Plato’s dialogues: the Just itself, the Beautiful, and the Good; Bigness, Health, and Strength; and “in a word, the reality of all other things, that which each of them essentially is” (65d). They are best approached not by sense perception but by pure thought alone. These entities are granted again without argument by Simmias and Cebes, and are discussed in more detail later. .

All told, then, the body is a constant impediment to philosophers in their search for truth: “It fills us with wants, desires, fears, all sorts of illusions and much nonsense, so that, as it is said, in truth and in fact no thought of any kind ever comes to us from the body” (66c). To have pure knowledge, therefore, philosophers must escape from the influence of the body as much as is possible in this life. Philosophy itself is, in fact, a kind of “training for dying” (67e), a purification of the philosopher’s soul from its bodily attachment.

Thus, Socrates concludes, it would be unreasonable for a philosopher to fear death, since upon dying he is most likely to obtain the wisdom which he has been seeking his whole life. Both the philosopher’s courage in the face of death and his moderation with respect to bodily pleasures which result from the pursuit of wisdom stand in stark contrast to the courage and moderation practiced by ordinary people. (Wisdom, courage, and moderation are key virtues in Plato’s writings, and are included in his definition of justice in the Republic.) Ordinary people are only brave in regard to some things because they fear even worse things happening, and only moderate in relation to some pleasures because they want to be immoderate with respect to others. But this is only “an illusory appearance of virtue”—for as it happens, “moderation and courage and justice are a purging away of all such things, and wisdom itself is a kind of cleansing or purification” (69b-c). Since Socrates counts himself among these philosophers, why wouldn’t he be prepared to meet death? Thus ends his defense.

b. Three Arguments for the Soul’s Immortality (69e-84b)

But what about those, says Cebes, who believe that the soul is destroyed when a person dies? To persuade them that it continues to exist on its own will require some compelling argument. Readers should note several important features of Cebes’ brief objection (70a-b). First, he presents the belief in the immortality of the soul as an uncommon belief (“men find it hard to believe . . .”). Secondly, he identifies two things which need to be demonstrated in order to convince those who are skeptical: (a) that the soul continues to exist after a person’s death, and (b) that it still possesses intelligence. The first argument that Socrates deploys appears to be intended to respond to (a), and the second to (b).

i. The Cyclical Argument (70c-72e)

Socrates mentions an ancient theory holding that just as the souls of the dead in the underworld come from those living in this world, the living souls come back from those of the dead (70c-d). He uses this theory as the inspiration for his first argument, which may be reconstructed as follows:

1. All things come to be from their opposite states: for example, something that comes to be “larger” must necessarily have been “smaller” before (70e-71a).

2. Between every pair of opposite states there are two opposite processes: for example, between the pair “smaller” and “larger” there are the processes “increase” and “decrease” (71b).

3. If the two opposite processes did not balance each other out, everything would eventually be in the same state: for example, if increase did not balance out decrease, everything would keep becoming smaller and smaller (72b).

4. Since “being alive” and “being dead” are opposite states, and “dying” and “coming-to-life” are the two opposite processes between these states, coming-to-life must balance out dying (71c-e).

5. Therefore, everything that dies must come back to life again (72a).

A main question that arises in regard to this argument is what Socrates means by “opposites.” We can see at least two different ways in which this term is used in reference to the opposed states he mentions. In a first sense, it is used for “comparatives” such as larger and smaller (and also the pairs weaker/stronger and swifter/slower at 71a), opposites which admit of various degrees and which even may be present in the same object at once (on this latter point, see 102b-c). However, Socrates also refers to “being alive” and “being dead” as opposites—but this pair is rather different from comparative states such as larger and smaller, since something can’t be deader, but only dead. Being alive and being dead are what logicians call “contraries” (as opposed to “contradictories,” such as “alive” and “not-alive,” which exclude any third possibility). With this terminology in mind, some contemporary commentators have maintained that the argument relies on covertly shifting between these different kinds of opposites.

Clever readers may notice other apparent difficulties as well. Does the principle about balance in (3), for instance, necessarily apply to living things? Couldn’t all life simply cease to exist at some point, without returning? Moreover, how does Plato account for adding new living souls to the human population? While these questions are perhaps not unanswerable from the point of view of the present argument, we should keep in mind that Socrates has several arguments remaining, and he later suggests that this first one should be seen as complementing the second (77c-d).

ii. The Argument from Recollection (72e-78b)

Cebes mentions that the soul’s immortality also is supported by Socrates’ theory that learning is “recollection” (a theory which is, by most accounts, distinctively Platonic, and one that plays a role in his dialogues Meno and Phaedrus as well). As evidence of this theory he mentions instances in which people can “recollect” answers to questions they did not previously appear to possess when this knowledge is elicited from them using the proper methods. This is likely a reference to the Meno (82b ff.), where Socrates elicits knowledge about basic geometry from a slave-boy by asking the latter a series of questions to guide him in the right direction. Asked by Simmias to elaborate further upon this doctrine, Socrates explains that recollection occurs “when a man sees or hears or in some other way perceives one thing and not only knows that thing but also thinks of another thing of which the knowledge is not the same but different . . .” (73c). For example, when a lover sees his beloved’s lyre, the image of his beloved comes into his mind as well, even though the lyre and the beloved are two distinct things.

Based on this theory, Socrates now commences a second proof for the soul’s immortality—one which is referred to with approval in later passages in the dialogue (77a-b, 87a, 91e-92a, and 92d-e). The argument may be reconstructed as follows:

1. Things in the world which appear to be equal in measurement are in fact deficient in the equality they possess (74b, d-e).

2. Therefore, they are not the same as true equality, that is, “the Equal itself” (74c).

3. When we see the deficiency of the examples of equality, it helps us to think of, or “recollect,” the Equal itself (74c-d).

4. In order to do this, we must have had some prior knowledge of the Equal itself (74d-e).

5. Since this knowledge does not come from sense-perception, we must have acquired it before we acquired sense-perception, that is, before we were born (75b ff.).

6. Therefore, our souls must have existed before we were born. (76d-e)

With regard to premise (1), in what respect are this-worldly instances of equality deficient? Socrates mentions that two apparently equal sticks, for example, “fall short” of true equality and are thus “inferior” to it (74e). Why? His reasoning at 74b8-9—that the sticks “sometimes, while remaining the same, appear to one to be equal and another to be unequal”—is notoriously ambiguous, and has been the subject of much scrutiny. He could mean that the sticks may appear as equal or unequal to different observers, or perhaps they appear as equal when measured against one thing but not another. In any case, the notion that the sensible world is imperfect is a standard view of the middle dialogues (see Republic 479b-c for a similar example), and is emphasized further in his next argument.

By “true equality” and “the Equal itself” in premises (2)-(4), Socrates is referring to the Form of Equality. It is this entity with respect to which the sensible instances of equality fall short—and indeed, Socrates says that the Form is “something else beyond all these.” His brief argument at 74a-c that true equality is something altogether distinct from any visible instances of equality is of considerable interest, since it is one of few places in the middle dialogues where he makes an explicit argument for why there must be Forms. The conclusion of the second argument for the soul’s immortality extends what has been said about equality to other Forms as well: “If those realities we are always talking about exist, the Beautiful and the Good and all that kind of reality, and we refer all the things we perceive to that reality, discovering that it existed before and is ours, and we compare these things with it, then, just as they exist, so our soul must exist before we are born” (76d-e). The process of recollection is initiated not just when we see imperfectly equal things, then, but when we see things that appear to be beautiful or good as well; experience of all such things inspires us to recollect the relevant Forms. Moreover, if these Forms are never available to us in our sensory experience, we must have learned them even before we were capable of having such experience.

Simmias agrees with the argument so far, but says that this still does not prove that our souls exist after death, but only before birth. This difficulty, Socrates suggests, can be resolved by combining the present argument with the one from opposites: the soul comes to life from out of death, so it cannot avoid existing after death as well. He does not elaborate on this suggestion, however, and instead proceeds to offer a third argument.

iii. The Affinity Argument (78b-84b)

The third argument for the soul’s immortality is referred to by commentators as the “affinity argument,” since it turns on the idea that the soul has a likeness to a higher level of reality:

1. There are two kinds of existences: (a) the visible world that we perceive with our senses, which is human, mortal, composite, unintelligible, and always changing, and (b) the invisible world of Forms that we can access solely with our minds, which is divine, deathless, intelligible, non-composite, and always the same (78c-79a, 80b).

2. The soul is more like world (b), whereas the body is more like world (a) (79b-e).

3. Therefore, supposing it has been freed of bodily influence through philosophical training, the soul is most likely to make its way to world (b) when the body dies (80d-81a). (If, however, the soul is polluted by bodily influence, it likely will stay bound to world (a) upon death (81b-82b).)

Note that this argument is intended to establish only the probability of the soul’s continued existence after the death of the body—“what kind of thing,” Socrates asks at the outset, “is likely to be scattered [after the death of the body]?” (78b; my italics) Further, premise (2) appears to rest on an analogy between the soul and body and the two kinds of realities mentioned in (1), a style of argument that Simmias will criticize later (85e ff.). Indeed, since Plato himself appends several pages of objections by Socrates’ interlocutors to this argument, one might wonder how authoritative he takes it to be.

Yet Socrates’ reasoning about the soul at 78c-79a states an important feature of Plato’s middle period metaphysics, sometimes referred to as his “two-world theory.” In this picture of reality, the world perceived by the senses is set against the world of Forms, with each world being populated by fundamentally different kinds of entities:

| The World of the Senses | The World of Forms |

| Composites (that is, things with parts) | Non-composites |

| Things that never remain the same from one moment to the next | Things that always remain the same and don’t tolerate any change |

| Any particular thing that is equal, beautiful, and so forth | The Equal, the Beautiful, and what each thing is in itself |

| That which is visible | That which is grasped by the mind and invisible |

Since the body is like one world and the soul like the other, it would be strange to think that even though the body lasts for some time after a person’s death, the soul immediately dissolves and exists no further. Given the respective affinities of the body and soul, Socrates spends the rest of the argument (roughly 80d-84b) expanding on the earlier point (from his “defense”) that philosophers should focus on the latter. This section has some similarities to the myth about the afterlife, which he narrates near the dialogue’s end; note that some of the details of the account here of what happens after death are characterized as merely “likely.” A soul which is purified of bodily things, Socrates says, will make its way to the divine when the body dies, whereas an impure soul retains its share in the visible after death, becoming a wandering phantom. Of the impure souls, those who have been immoderate will later become donkeys or similar animals, the unjust will become wolves or hawks, those with only ordinary non-philosophical virtue will become social creatures such as bees or ants.

The philosopher, on the other hand, will join the company of the gods. For philosophy brings deliverance from bodily imprisonment, persuading the soul “to trust only itself and whatever reality, existing by itself, the soul by itself understands, and not to consider as true whatever it examines by other means, for this is different in different circumstances and is sensible and visible, whereas what the soul itself sees is intelligible and indivisible” (83a6-b4). The philosopher thus avoids the “greatest and most extreme evil” that comes from the senses: that of violent pleasures and pains which deceive one into thinking that what causes them is genuine. Hence, after death, his soul will join with that to which it is akin, namely, the divine.

c. Objections from Simmias and Cebes, and Socrates’ Response (84c-107b)

After a long silence, Socrates tells Simmias and Cebes not to worry about objecting to any of what he has just said. For he, like the swan that sings beautifully before it dies, is dedicated to the service of Apollo, and thus filled with a gift of prophecy that makes him hopeful for what death will bring.

i. The Objections (85c-88c)

Simmias prefaces his objection by making a remark about methodology. While certainty, he says, is either impossible or difficult, it would show a weak spirit not to make a complete investigation. If at the end of this investigation one fails to find the truth, one should adopt the best theory and cling to it like a raft, either until one dies or comes upon something sturdier.

This being said, he proceeds to challenge Socrates’ third argument. For one might put forth a similar argument which claims that the soul is like a harmony and the body is like a lyre and its strings. In fact, Simmias claims that “we really do suppose the soul to be something of this kind,” that is, a harmony or proper mixture of bodily elements like the hot and cold or dry and moist (86b-c). (Some commentators think the “we” here refers to followers of Pythagoras.) But even though a musical harmony is invisible and akin to the divine, it will cease to exist when the lyre is destroyed. Following the soul-as-harmony thesis, the same would be true of the soul when the body dies.

Next Socrates asks if Cebes has any objections. The latter says that he is convinced by Socrates’ argument that the soul exists before birth, but still doubts whether it continues to exist after death. In support of his doubt, he invokes a metaphor of his own. Suppose someone were to say that since a man lasts longer than his cloak, it follows that if the cloak is still there the man must be there too. We would certainly think this statement was nonsense. (He appears to be refering to Socrates’ argument at 80c-e here.) Just as a man might wear out many cloaks before he dies, the soul might use up many bodies before it dies. So even supposing everything else is granted, if “one does not further agree that the soul is not damaged by its many births and is not, in the end, altogether destroyed in one of those deaths, he might say that no one knows which death and dissolution of the body brings about the destruction of the soul, since not one of us can be aware of this” (88a-b). In light of this uncertainty, one should always face death with fear.

ii. Interlude on Misology (89b-91c)

After a short exchange in the meta-dialogue in which Phaedo and Echecrates praise Socrates’ pleasant attitude throughout this discussion, Socrates begins his response with a warning that they not become misologues. Misology, he says, arises in much the same way that misanthropy does: when someone with little experience puts his trust in another person, but later finds him to be unreliable, his first reaction is to blame this on the depraved nature of people in general. If he had more knowledge and experience, however, he would not be so quick to make this leap, for he would realize that most people fall somewhere in between the extremes of good and bad, and he merely happened to encounter someone at one end of the spectrum. A similar caution applies to arguments. If someone thinks a particular argument is sound, but later finds out that it is not, his first inclination will be to think that all arguments are unsound; yet instead of blaming arguments in general and coming to hate reasonable discussion, we should blame our own lack of skill and experience.

iii. Response to Simmias (91e-95a)

Socrates then puts forth three counter-arguments to Simmias’ objection. To begin, he gets both Simmias and Cebes to agree that the theory of recollection is true. But if this is so, then Simmias is not able to “harmonize” his view that the soul is a harmony dependent on the body with the recollection view that the soul exists before birth. Simmias admits this inconsistency, and says that he in fact prefers the theory of recollection to the other view. Nonetheless, Socrates proceeds to make two additional points. First, if the soul is a harmony, he contends, it can have no share in the disharmony of wickedness. But this implies that all souls are equally good. Second, if the soul is never out of tune with its component parts (as shown at 93a), then it seems like it could never oppose these parts. But in fact it does the opposite, “ruling over all the elements of which one says it is composed, opposing nearly all of them throughout life, directing all their ways, inflicting harsh and painful punishment on them, . . . holding converse with desires and passions and fears, as if it were one thing talking to a different one . . .” (94c9-d5). A passage in Homer, wherein Odysseus beats his breast and orders his heart to endure, strengthens this picture of the opposition between soul and bodily emotions. Given these counter-arguments, Simmias agrees that the soul-as-harmony thesis cannot be correct.

iv. Response to Cebes (95a-107b)

1. Socrates’ Intellectual History (96a-102a)

After summarizing Cebes’ objection that the soul may outlast the body yet not be immortal, Socrates says that this problem requires “a thorough investigation of the cause of generation and destruction” (96a; the Greek word aitia, translated as “cause,” has the more general meaning of “explanation”). He now proceeds to relate his own examinations into this subject, recalling in turn his youthful puzzlement about the topic, his initial attraction to a solution given by the philosopher Anaxagoras (500-428 B.C.), and finally his development of his own method of explanation involving Forms. It is debated whether this account is meant to describe Socrates’ intellectual autobiography or Plato’s own, since the theory of Forms generally is described as the latter’s distinctive contribution. (Some commentators have suggested that it may be neither, but instead just good storytelling on Plato’s part.)

When Socrates was young, he says, he was excited by natural science, and wanted to know the explanation of everything from how living things are nourished to how things occur in the heavens and on earth. But then he realized that he had no ability for such investigations, since they caused him to unlearn many of the things he thought he had previously known. He used to think, for instance, that people grew larger by various kinds of external nourishment combining with the appropriate parts of our bodies, for example, by food adding flesh to flesh. But what is it which makes one person larger than another? Or for that matter, which makes one and one add up to two? It seems like it can’t be simply the two things coming near one another. Because of puzzles like these, Socrates is now forced to admit his ignorance: “I do not any longer persuade myself that I know why a unit or anything else comes to be, or perishes or exists by the old method of investigation, and I do not accept it, but I have a confused method of my own” (97b).

This method came about as follows. One day after his initial setbacks Socrates happened to hear of Anaxagoras’ view that Mind directs and causes all things. He took this to mean that everything was arranged for the best. Therefore, if one wanted to know the explanation of something, one only had to know what was best for that thing. Suppose, for instance, that Socrates wanted to know why the heavenly bodies move the way they do. Anaxagoras would show him how this was the best possible way for each of them to be. And once he had taught Socrates what the best was for each thing individually, he then would explain the overall good that they all share in common. Yet upon studying Anaxagoras further, Socrates found these expectations disappointed. It turned out that Anaxagoras did not talk about Mind as cause at all, but rather about air and ether and other mechanistic explanations. For Socrates, however, this sort of explanation was simply unacceptable:

To call those things causes is too absurd. If someone said that without bones and sinews and all such things, I should not be able to do what I decided, he would be right, but surely to say that they are the cause of what I do, and not that I have chosen the best course, even though I act with my mind, is to speak very lazily and carelessly. Imagine not being able to distinguish the real cause from that without which the cause would not be able to act as a cause. (99a-b)

Frustrated at finding a teacher who would provide a teleological explanation of these phenomena, Socrates settled for what he refers to as his “second voyage” (99d). This new method consists in taking what seems to him to be the most convincing theory—the theory of Forms—as his basic hypothesis, and judging everything else in accordance with it. In other words, he assumes the existence of the Beautiful, the Good, and so on, and employs them as explanations for all the other things. If something is beautiful, for instance, the “safe answer” he now offers for what makes it such is “the presence of,” or “sharing in,” the Beautiful (100d). Socrates does not go into any detail here about the relationship between the Form and object that shares in it, but only claims that “all beautiful things are beautiful by the Beautiful” (100d). In regard to the phenomena that puzzled him as a young man, he offers the same answer. What makes a big thing big, or a bigger thing bigger, is the Form Bigness. Similarly, if one and one are said to be two, it is because they share in Twoness, whereas previously each shared in Oneness.

2. The Final Argument (102b-107b)

When Socrates has finished describing this method, both Simmias and Cebes agree that what he has said is true. Their accord with his view is echoed in another brief interlude by Echecrates and Phaedo, in which the former says that Socrates has “made these things wonderfully clear to anyone of even the smallest intelligence,” and Phaedo adds that all those present agreed with Socrates as well. Returning again to the prison scene, Socrates now uses this as the basis of a fourth argument that the soul is immortal. One may reconstruct this argument as follows:

1. Nothing can become its opposite while still being itself: it either flees away or is destroyed at the approach of its opposite. (For example, “tallness” cannot become “shortness” while still being “tall.”) (102d-103a)

2. This is true not only of opposites, but in a similar way of things that contain opposites. (For example, “fire” and “snow” are not themselves opposites, but “fire” always brings “hot” with it, and “snow” always brings “cold” with it. So “fire” will not become “cold” without ceasing to be “fire,” nor will “snow” become “hot” without ceasing to be “snow.”) (103c-105b)

3. The “soul” always brings “life” with it. (105c-d)

4. Therefore “soul” will never admit the opposite of “life,” that is, “death,” without ceasing to be “soul.” (105d-e)

5. But what does not admit death is also indestructible. (105e-106d)

6. Therefore, the soul is indestructible. (106e-107a)

When someone objects that premise (1) contradicts his earlier statement (at 70d-71a) about opposites arising from one another, Socrates responds that then he was speaking of things with opposite properties, whereas here is talking about the opposites themselves. Careful readers will distinguish three different ontological items at issue in this passage:

(a) the thing (for example, Simmias) that participates in a Form (for example, that of Tallness), but can come to participate in the opposite Form (of Shortness) without thereby changing that which it is (namely, Simmias)

(b) the Form (for example, of Tallness), which cannot admit its opposite (Shortness)

(c) the Form-in-the-thing (for example, the tallness in Simmias), which cannot admit its opposite (shortness) without fleeing away of being destroyed

Premise (2) introduces another item:

(d) a kind of entity (for example, fire) that, even though it does not share the same name as a Form, always participates in that Form (for example, Hotness), and therefore always excludes the opposite Form (Coldness) wherever it (fire) exists

This new kind of entity puts Socrates beyond the “safe answer” given before (at 100d) about how a thing participates in a Form. His new, “more sophisticated answer” is to say that what makes a body hot is not heat—the safe answer—but rather an entity such as fire. In like manner, what makes a body sick is not sickness but fever, and what makes a number odd is not oddness but oneness (105b-c). Premise (3) then states that the soul is this sort of entity with respect to the Form of Life. And just as fire always brings the Form of Hotness and excludes that of Coldness, the soul will always bring the Form of Life with it and exclude its opposite.

However, one might wonder about premise (5). Even though fire, to return to Socrates’ example, does not admit Coldness, it still may be destroyed in the presence of something cold—indeed, this was one of the alternatives mentioned in premise (1). Similarly, might not the soul, while not admitting death, nonetheless be destroyed by its presence? Socrates tries to block this possibility by appealing to what he takes to be a widely shared assumption, namely, that what is deathless is also indestructible: “All would agree . . . that the god, and the Form of Life itself, and anything that is deathless, are never destroyed” (107d). For readers who do not agree that such items are deathless in the first place, however, this sort of appeal is unlikely to be acceptable.

Simmias, for his part, says he agrees with Socrates’ line of reasoning, although he admits that he may have misgivings about it later on. Socrates says that this is only because their hypotheses need clearer examination—but upon examination they will be found convincing.

d. The Myth about the Afterlife (107c-115a)

The issue of the immortality of the soul, Socrates says, has considerable implications for morality. If the soul is immortal, then we must worry about our souls not just in this life but for all time; if it is not, then there are no lasting consequences for those who are wicked. But in fact, the soul is immortal, as the previous arguments have shown, and Socrates now begins to describe what happens when it journeys to the underworld after the death of the body. The ensuing tale tells us of

(1) the judgment of the dead souls and their subsequent journey to the underworld (107d-108c)

(2) the shape of the earth and its regions (108c-113c)

(3) the punishment of the wicked and the reward of the pious philosophers (113d-114c)

Commentators commonly refer to this story as a “myth,” and Socrates himself describes it this way (using the Greek word muthos at 110b, which earlier on in the dialogue (61b) he has contrasted with logos, or “argument.”). Readers should be aware that for the Greeks myth did not have the negative connotations it often carries today, as when we say, for instance, that something is “just a myth” or when we distinguish myth from fact. While Plato’s relation to traditional Greek mythology is a complex one—see his critique of Homer and Hesiod in Republic Book II, for instance—he himself uses myths to bolster his doctrines not only in the Phaedo, but in dialogues such as the Gorgias, Republic, and Phaedrus as well.

At the end of his tale, Socrates says that what is important about his story is not its literal details, but rather that we “risk the belief” that “this, or something like this, is true about our souls and their dwelling places,” and repeat such a tale to ourselves as though it were an “incantation” (114d). Doing so will keep us in good spirits as we work to improve our souls in this life. The myth thus reinforces the dialogue’s recommendation of the practice of philosophy as care for one’s soul.

e. Socrates’ Death (115a-118a)

The depiction of Socrates’ death that closes the Phaedo is rich in dramatic detail. It also is complicated by a couple of difficult interpretative questions.

After Socrates has finished his tale about the afterlife, he says that it is time for him to prepare to take the hemlock poison required by his death sentence. When Crito asks him what his final instructions are for his burial, Socrates reminds him that what will remain with them after death is not Socrates himself, but rather just his body, and tells him that they can bury it however they want. Next he takes a bath—so that his corpse will not have to be cleaned post-mortem—and says farewell to his wife and three sons. Even the officer sent to carry out Socrates’ punishment is moved to tears at this point, and describes Socrates as “the noblest, the gentlest and the best man” who has ever been at the prison.

Crito tells Socrates that some condemned men put off taking the poison for as long as possible, in order to enjoy their last moments in feasting or sex. Socrates, however, asks for the poison to be brought immediately. He drinks it calmly and in good cheer, and chastises his friends for their weeping. When his legs begin to feel heavy, he lies down; the numbness in his body travels upward until eventually it reaches his heart.

Some contemporary scholars have challenged Plato’s description of hemlock-poisoning, arguing that in fact the symptoms would have been much more violent than the relatively gentle death he depicts. If these scholars are right, why does Plato depict the death scene the way he does? There is also a dispute about Socrates’ last words, which invoke a sacrificial offering made by the sick to the god of medicine: “Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius; make this offering to him and do not forget.” Did Socrates view life as a kind of sickness?

4. References and Further Reading

a. General Commentaries

- Bostock, D. Plato’s Phaedo. Oxford, 1986.

- In-depth yet accessible discussion of the dialogue’s arguments (does not include text of the Phaedo). Includes a helpful chapter on the theory of Forms.

- Dorter, K. Plato’s Phaedo: An Interpretation. University of Toronto Press, 1982.

- Reading of the dialogue that combines both dramatic and doctrinal approaches (does not include text of the Phaedo).

- Gallop, D. Plato: Phaedo. Oxford, 1975.

- English translation with separate commentary that focuses on the dialogue’s argumentation.

- Hackforth, R. Plato’s Phaedo: Translated with an Introduction and Commentary. Cambridge, 1955.

- English translation with running commentary.

- Rowe, C.J. Plato: Phaedo. Cambridge, 1993.

- Original Greek text (no English) with introduction and detailed textual commentary.

b. The Philosopher and Death (59c-69e)

- Pakaluk, M. “Degrees of Separation in the ‘Phaedo.’” Phronesis 48 (2003) 89-115.

- Discusses Plato’s notion of the soul-body distinction at 63a-69e.

- Warren, J. “Socratic Suicide.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 121 (2001) 91-106.

- On the Platonic philosopher’s attitude toward suicide in the 61e-69e passage.

- Weiss, R. “The Right Exchange: Phaedo 69a6-c3″. Ancient Philosophy 7 (1987) 57-66.

- Examines the notion that wisdom is the highest goal of the philosopher.

c. Three Arguments for the Soul’s Immortality (69e-84b)

- Ackrill, J.L. “Anamnēsis in the Phaedo,” in E.N. Lee and A.P.D. Mourelatos (eds.) Exegesis and Argument: Studies in Greek Philosophy Presented to Gregory Vlastos. Assen, 1973. 177-95.

- On the theory of recollection (73c-75).

- Apolloni, D. “Plato’s Affinity Argument for the Immortality of the Soul.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 34 (1996) 5-32.

- A study of the argument at 78b-80d.

- Gallop, D. “Plato’s ‘Cyclical Argument’ Recycled.” Phronesis 27 (1982) 207-222.

- On the first argument for the soul’s immortality (69e-72e) and its relation to the other arguments.

- Matthen, M. “Forms and Participants in Plato’s Phaedo.” Noûs 18:2 (1984) 281-297.

- Discusses Plato’s argument concerning equals at 74b7-c6.

- Nehamas, A. “Plato on the Imperfection of the Sensible World,” in G. Fine, ed., Plato 1: Metaphysics and Epistemology. Oxford, 1999. 171-191.

- On Plato’s view of sensible particulars, especially at 72e-78b.

d. Objections from Simmias and Cebes, and Socrates’ Response (84c-107b)

- Frede, D. “The Final Proof of the Immortality of the Soul in Plato’s Phaedo 102a-107a.” Phronesis 23 (1978) 27-41.

- A defense of Plato’s argument and examination of its underlying assumptions regarding the soul.

- Gottschalk, H.D. “Soul as Harmonia.” Phronesis 16 (1971) 179-198.

- Discusses Simmias’ account of the soul beginning at 85e.

- Vlastos, G. “Reasons and Causes in the Phaedo,” in Plato: A Collection of Critical Essays, Vol. I: Metaphysics and Epistemology. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1971.

- Are Forms causes? An examination of 95e-105c.

- Wiggins, D. “Teleology and the Good in Plato’s Phaedo.” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 4 (1986) 1-18.

- On Socrates’ “second voyage” beginning at 99c2-d1.

e. The Myth about the Afterlife (107c-115a)

- Annas, J. “Plato’s Myths of Judgment.” Phronesis 27 (1982) 119-43.

- A study of Plato’s myths in the Gorgias, Phaedo, and Republic.

- Morgan, K.A. Myth and Philosophy from the pre-Socratics to Plato. Cambridge, 2000.

- Includes extensive background on myth in Plato, as well as discussion of the Phaedo myth in particular.

- Sedley, D. “Teleology and Myth in the Phaedo.” Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy 5 (1990) 359–83.

f. Socrates’ Death (115a-118a)

- Crook, J. “Socrates’ Last Words: Another Look at an Ancient Riddle.” Classical Quarterly 48 (1998) 117-125.

- The papers by Crook and Most (cited below) consider some puzzles regarding Socrates’ final words at the dialogue’s end.

- Gill, C. “The Death of Socrates.” Classical Quarterly 23 (1973) 25-25.

- On the finer details of hemlock-poisoning.

- Most, G.W. “A Cock for Asclepius.” Classical Quarterly 43 (1993) 96-111.

- Stewart, D. “Socrates’ Last Bath.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 10 (1972) 253-9.

- Looks at the deeper meaning of Socrates’ bath at 116a.

- Wilson, E. The Death of Socrates. Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Includes discussion of the death scene in the Phaedo, as well as its subsequent reception in Western philosophy, art, and culture.

Author Information

Tim Connolly

Email: tconnolly@po-box.esu.edu

East Stroudsburg University

U. S. A.

Josiah Royce was one of the most influential philosophers of the period of classical

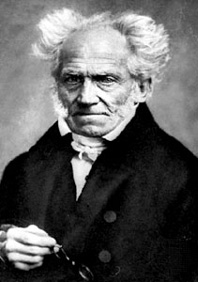

Josiah Royce was one of the most influential philosophers of the period of classical  Arthur Schopenhauer has been dubbed the artist’s philosopher on account of the inspiration his aesthetics has provided to artists of all stripes. He is also known as the philosopher of pessimism, as he articulated a worldview that challenges the value of existence. His elegant and muscular prose earns him a reputation as one of the greatest German stylists. Although he never achieved the fame of such post-Kantian philosophers as

Arthur Schopenhauer has been dubbed the artist’s philosopher on account of the inspiration his aesthetics has provided to artists of all stripes. He is also known as the philosopher of pessimism, as he articulated a worldview that challenges the value of existence. His elegant and muscular prose earns him a reputation as one of the greatest German stylists. Although he never achieved the fame of such post-Kantian philosophers as