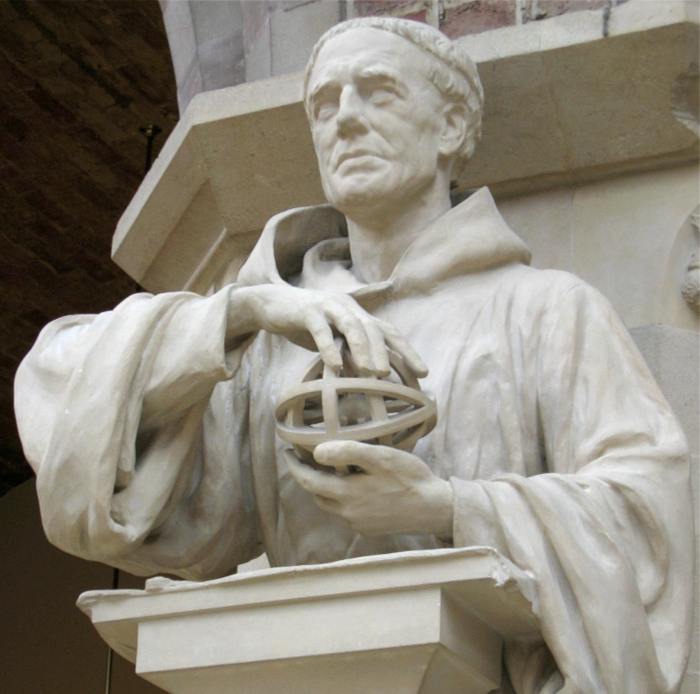

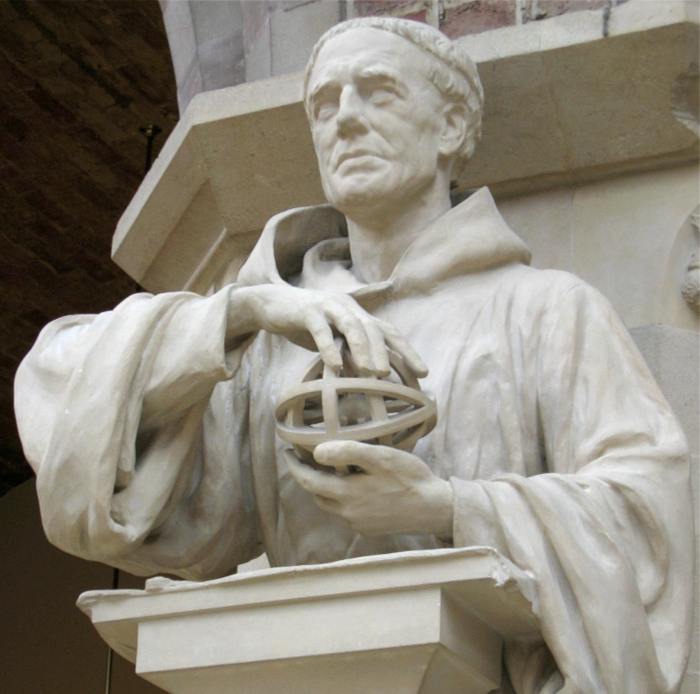

Roger Bacon (1214–1292)

Roger Bacon’s most noteworthy philosophical accomplishments were in the fields of mathematics, natural sciences, and language studies. A conspicuous feature of his philosophical outlook was his emphasis on the utility and practicality of all scientific efforts. Bacon was convinced that mathematics and astronomy are not morally neutral activities, pursued for their own sake, but have a deep connection to the practical business of everyday life. Bacon was committed to the view that wisdom should contribute to the improvement of life. For example, his extensive works on the reform and reorganization of the university curriculum were, on the surface, aimed at reforming the study of theology; yet, ultimately, they contained a political program whose goal was to civilize humankind as well as to secure peace and prosperity for the whole of the Christian world, both in the hereafter and in this world.

Roger Bacon’s most noteworthy philosophical accomplishments were in the fields of mathematics, natural sciences, and language studies. A conspicuous feature of his philosophical outlook was his emphasis on the utility and practicality of all scientific efforts. Bacon was convinced that mathematics and astronomy are not morally neutral activities, pursued for their own sake, but have a deep connection to the practical business of everyday life. Bacon was committed to the view that wisdom should contribute to the improvement of life. For example, his extensive works on the reform and reorganization of the university curriculum were, on the surface, aimed at reforming the study of theology; yet, ultimately, they contained a political program whose goal was to civilize humankind as well as to secure peace and prosperity for the whole of the Christian world, both in the hereafter and in this world.

During his long and productive life, he was a Master of Arts and Franciscan friar who was committed to a philosophical outlook that was deeply imbued with Christian principles as well as scientific curiosity and ambition. In many cases, his ideas betray him as a child of his time, and yet his thinking was well in advance of his contemporaries.

Bacon is noteworthy for being one of the West’s first commentators and lecturers on Aristotle‘s philosophy and science. He has been called Doctor Mirabilis (wonderful teacher) and described variously as a rebel, traditionalist, reactionary, martyr to scientific progress, and the first modern scientist. Unfortunately, these romantic epithets tend to blur the actual nature of his philosophical achievements.

Table of Contents

- Life and Works

- Life

- Works

- Early Works: 1240s–1250s

- Works for Pope Clement IV: 1266–1268

- Later Works: Late 1260s–1292

- The General Trajectory of Roger Bacon’s Philosophy

- Utility and Wisdom

- The Critique of University Learning

- Reform of Education

- Human Happiness and the Sciences

- Bacon on Language

- Mathematics and Natural Sciences

- General Remarks

- Bacon’s Modification of the Quadrivium

- Bacon’s Scientific Views and the Condemnation of 1277

- The Nature and Value of Mathematics

- The Object and Division of Mathematics

- The Methodological Relevance of Mathematics

- The Physical Relevance of Mathematics

- Bacon’s Theory of Physical Causation and Perspective

- Experimental Science

- Experience and Experiment

- The Three Prerogatives of Experimental Science

- Bacon as Experimenter

- Alchemy and Medicine

- Moral Philosophy

- General Scope and Nature of Bacon’s Moral Philosophy

- Morality and Happiness

- The Place of Moral Philosophy within the Hierarchy of Sciences

- Practical Sciences and Human Practice

- The Functional Division of Moral Philosophy

- Moral Philosophy in the Service of Human Moral Agency

- The Conversion of Non-Christians

- Moral Works and Eloquence

- Rhetoric and Poetics as Branches of Moral Philosophy

- Conclusion

- References and Further Reading

- Bibliographies

- Primary Sources

- 1240s–1250s

- 1250s–1268

- 1268–1292

- Secondary Sources

1. Life and Works

a. Life

Any attempt to reconstruct Bacon’s life must rely on very few sources, among which the most important is one of Bacon’s own works, Opus Tertium (c. 1267). Since Bacon’s personal report is ambiguous, his biographical data as well as the chronology of his education and career are still a matter of dispute among scholars. Scholars argue as to whether he was born in 1210, 1214, 1215, or even as late as 1220. Despite these disagreements, it is at least agreed that, in view of the funds available to him to pursue his private research, he was likely born into a well-to-do family.

Bacon described his intellectual biography as being divided into two distinct periods: a first “secular” period lasting until around 1257, during which he worked as an academic, and a second period, which he spent as a Franciscan friar “in the pursuit of wisdom.” As a secular scholar, Bacon pursued his academic career at two of the earliest European universities. First he attended the University of Oxford and then the University of Paris. He probably earned his Master of Arts around 1240 and continued his career as a lecturer in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Paris throughout the 1240s. He probably resigned from his post as Regent Master of Arts in Paris in 1247 and returned to Oxford. After this time, Bacon does not seem to have ever held academic office again. The next ten years of Bacon’s life have proven difficult for scholars to reconstruct. It is known that during this time Bacon continued to pursue his scientific and linguistic studies. During this time he probably also received some training in theology by Adam Marsh (d. 1258), the first Regent Master of the Franciscans in Oxford. This training, however, never culminated in a degree in theology. In or around 1257, he joined the Franciscan Order, probably in Oxford. The exact reasons for why he chose this order are unknown, but there are reasons to think that he hoped the Franciscans would support his scholarly interests. After all, the Oxford Franciscans had attracted prominent scholars such as Robert Grosseteste (d. 1253) and Adam Marsh.

The beginning of the 1260s found Bacon again in Paris. It has been speculated that he was transferred there by the superiors of his order because of growing suspicion about his scientific studies. While in Paris, he finished several of his major works, including Opus Maius (OM), Opus Minus (OMi), and Opus Tertium (OT). The exact details of Bacon’s whereabouts and doings in the decades before his death remain uncertain. It seems clear, however, that he returned to Oxford sometime after 1278. Between 1277 and 1279, he was supposedly condemned to house arrest by the Franciscans’ Master General Jerome of Ascoli. The charge against him was that some of his doctrines contained “certain suspected novelties.” What these novelties were—whether relating to his teachings on alchemy, astronomy, experimental science, or his radical spiritual leanings—cannot be determined with precision (Easton, 1952, 192-202). Bacon’s punishment can likely be explained in the context of the Parisian Condemnations of 1270 and 1277. In the last years of his life, Bacon continued to work on what was, in all likelihood, his last treatise, Compendium Studii Theologie. He died in 1292, or soon thereafter, in Oxford.

b. Works

i. Early Works: 1240s–1250s

During his time at the Faculty of Arts at the University of Paris, Bacon lectured on many Aristotelian texts, the so-called libri naturales, including On the Soul, On Sense and the Sensible, Physics, Metaphysics, and probably On Generation and Corruption. Not all of these lectures have survived. We possess copies of two lectures on Physics, three lectures on different books of Metaphysics as well as lectures on the pseudo-Aristotelian works, Book of Causes and On Plants. The form of these lectures is that of quaestiones, or ‘questions’, which involve the presentation of expository and critical questions combined with explanatory comments. These lectures represent Bacon’s earliest teachings on topics such as causality, motion, being, soul, substance, and truth. Bacon’s quaestiones were not written by Bacon himself, but consist in notes that his students took during his lectures. These notes might have been checked later by Bacon for accuracy. With the exception of a set of quaestiones on Physics II–IV, these writings survive in one single manuscript. These lectures—together with the lectures of Richard Rufus of Cornwall (d. 1260) —mark some of the earliest known examinations of Aristotle’s Metaphysics and the libri naturales from the Faculty of Arts at Paris.

During the 1240s and 1250s, Bacon composed a series of works on logical and grammatical matters dealing with syntactic as well as semantic issues. These include the Summa Grammatica (‘Summary of Grammar’; c. 1245), Summa de Sophismatibus et Distinctionibus (‘Summary of Sophisms and Distinctions’; c. 1240–1245) and Summulae Dialectices (‘Summary of Dialectics’; probably completed after Bacon’s return to Oxford in the 1250s). These works show that Bacon was one of the earliest proponents of the so-called terminist logic. Terminist logic was referred to by medieval scholars as Logica Modernorum or Moderna (‘contemporary logic’), and was originated by scholars such as William of Sherwood (d. 1266/72) and Petrus Hispanus (d. 1277). Contemporary logic was so-called by the medieval masters themselves in order to describe and distinguish their new, contextual approach toward logic, which consisted in an emphasis on the analysis of the signifying properties of terms in a propositional as well as a pragmatic context.

Sometime in the late 1250s or early 1260s Bacon composed another treatise entitled De Multiplicatione Specierum (‘On the Multiplication of Species’). In this work Bacon developed a doctrine that he considered to be central to his natural philosophy. Specifically, he aimed in this work to explain natural causation through the concept of species; more will be said about this matter this below.

ii. Works for Pope Clement IV: 1266–1268

The works for which Bacon is most widely known are a group of writings commissioned by Pope Clement IV, comprising the Opus Maius, Opus Minus, and Opus Tertium. All of these works are rhetorical in the sense that Bacon attempted to persuade the Pope to support his research and to help him to implement his projected reform of studies. The reform program suggested by Bacon was very extensive and encompassed the study of languages, mathematics, the natural sciences, moral philosophy, and theology.

The circumstances under which Bacon composed these works are well documented in his own statements. Sometime in the early 1260s, Bacon sought the patronage of Cardinal Guy de Foulques, papal legate to England during the Civil War. From the ensuing correspondence it became clear that the cardinal would not provide the funds Bacon needed to complete his writings but that he was nevertheless interested in Bacon’s reform ideas. He asked Bacon to send him his writings. Bacon had nothing to send to the cardinal, however, because completing his works required money for books, scientific equipment, and copyists—money Bacon did not have. In 1265, however, the situation changed dramatically when Cardinal Guy de Foulques was elected Pope Clement IV. Bacon soon sent the new Pope a letter asking for aid, to which the Pope replied in June 1266, asking Bacon to send the writings containing “the remedies for the critical problems” Bacon had mentioned to him a few years before and to do so “as quickly and secretly as possible.” Yet, in 1266 Bacon’s financial needs were no different from a few years before. In addition to Bacon’s financial predicament, there was another complicating factor at work: the Franciscan Order was in a time of crisis over dogmatic issues, and in response to these issues, the General chapter at Narbonne (1260) imposed strict censorship on the Order and forbade direct communication with the papal curia. Under these conditions—insufficient funds, time pressure, forbidden communication with the Pope, and growing suspicion within the order against Bacon’s own scientific and spiritual leanings—Bacon was forced to compose a much shorter, more rhetorical work (or persuasio), rather than the longer work (scriptum principale) he originally envisioned. In a short period of time, Bacon completed several writings, rhetorically structured in a way so as to best persuade the Pope of his ideas. Late in 1267 or early in 1268 he sent out the Opus Maius, partly patched together from previous writings, and the Opus Minus. It was common practice for Bacon to borrow from his other works; the fourth part of the Opus Maius contained an abbreviation of the earlier De Multiplicatione Specierum. The Opus Tertium was probably never sent. The works arrived safely. However, since the Pope died in 1268, it remains unknown whether he had a chance to study Bacon’s works, and, if he did, how he received them.

iii. Later Works: Late 1260s–1292

Although historical evidence for Bacon’s whereabouts during the final stage of his career is scarce, it is certain that he remained active. In the late 1260s and early 1270s, while still in Paris, he may have worked on the Communia Mathematica and Communia Naturalium; the polemic Compendium Studii Philosophiae (CSP) was probably written around 1272. He put together basic grammars for both Greek and Hebrew, and he also wrote two medical treatises, De Erroribus Medicorum and Antidotarius. Sometime in the two decades before his death, he completed his elaborate edition of the pseudo-Aristotelian Secretum Secretorum for which he prepared a redaction of the text, annotated it, and wrote an accompanying introductory treatise (Williams, 1994). His last work, written when he was around seventy years old, was a treatise on semiotics, the Compendium Studii Theologie, which is incomplete.

2. The General Trajectory of Roger Bacon’s Philosophy

a. Utility and Wisdom

The length of Bacon’s career and the diversity of his philosophical interests and accomplishments make it impossible to capture his philosophy in a simple summary. In regard to Bacon’s work on Aristotle and the Arab commentators during his first stay in Paris, one could speak of Bacon as a pioneer in Aristotelian studies. Yet these early works give little hint of his later and much more specialized interests in science, semantics, moral philosophy, and Christian theology. Bacon’s later work as a Franciscan scholar differed significantly from his earlier work in both content and purpose.

A possible reason for the change in Bacon’s scholarly interests may have been his encounter with the pseudo-Aristotelian work Secretum Secretorum while at Paris during the 1240s. The Secretum Secretorum was composed in the form of a pseudo-epigraphical letter from Aristotle to Alexander the Great, belonging to the literary genre mirrors for princes. With the purpose of providing insight into the art of government, the anonymous author treats of secret doctrines useful to a political ruler, among which are ethics, alchemy, and medicine. It might be the case that Bacon, after reading the Secretum, was inspired to develop the vision that henceforth guided his philosophical efforts and consisted of a conception of Christian learning applicable to the needs of humankind, both worldly and otherworldly. For a critical evaluation of the supposed influence of the Secretum Secretorum on Bacon’s views see Williams, 1997, 368-372. The principles around which his thoughts subsequently developed had a strong connection to concrete socio-political affairs, and his outlook on the sciences became focused on applicability, practicality, and usefulness. This practical outlook on the sciences, as being in the service of humankind, manifested itself in positive and negative remarks made in writings like the Opus Maius or Compendium Studii Philosophiae. His negative remarks consisted of incessant critiques of what he perceived to be the desolate, that is, practically useless, state of learning during his time. His positive remarks focused on proposals about the benefits and possibilities of the practical application of the different branches of knowledge.

The medieval use of the term science should not be confused with the modern use, which is distinct from philosophical and theological inquiry. Rather, 13th century thinkers understood the term science in accordance with the Aristotelian framework of epistemic or apodeictic knowledge. According to Aristotle in Posterior Analytics, science denotes intellectual comprehension of a true, necessary, and universal proposition, known or presented in the form of a demonstrative proof and providing an understanding of why the proposition is true. In other words, Aristotelian science involves knowledge of a reasoned fact—an understanding of science that is far broader than the modern understanding of empirical science. Despite the fact that almost all scholastics endorsed the Aristotelian paradigm of science, there was wide variation in the medieval scholars’ accounts of the foundation and scope of Aristotelian science, depending on their ontological, epistemological, and logical commitments. Bacon, like other thinkers, oftentimes used the terms science and philosophy interchangeably, thereby referring to a group of disciplines that conform to the aforementioned Aristotelian paradigm. According to Bacon, the sciences or philosophy comprise disparate disciplines such as moral philosophy and metaphysics.

The pivotal concepts around which all of Bacon’s philosophical efforts revolved were utilitas (‘utility’) and sapientia (‘wisdom’). Bacon used the concept of utility in the context of his reflections on the relation, scope, and goal of the sciences. More specifically, he used the term in two senses: (1) to describe the hierarchy between the sciences and (2) to refer to the function of the sciences, namely, the improvement of the physical and spiritual well-being of humankind in this world and the next. With respect to the hierarchy of the sciences, he regarded the theoretical sciences to be subordinate to the practical sciences. For him, the former is instrumental in achieving the goals of the latter. Here it is important to keep in mind that Bacon’s conception of philosophy did not entail the patristic idea that philosophy is merely a handmaiden of theology (philosophia ancilla theologiae). Philosophy, although useful for theology, is not reduced to theology. On the contrary, Bacon believed that theology, in order to fulfill its purpose, was heavily reliant on philosophy (OM II, vol. 3, 36). And yet, the utility of both philosophy and theology ultimately refer to the God-ordained purpose of the created world, which Bacon recognized in the return of all creatures to their divine origin.

Concerning wisdom, Bacon uses the term to refer to the complete body of knowledge given by God to humankind for the purpose of humankind’s happiness and salvation. In a sense, all knowledge for Bacon was contained in the Scriptures and should be unfolded by philosophy and canon law. The manner, however, in which philosophy unfolds the basic truths in the Scriptures is different from the manner of theology. According to Bacon, these “exegetic” disciplines, philosophy and canon law, were first revealed to the early prophets and patriarchs and then handed down through generations of true “lovers of wisdom, ” like prophets, patriarchs, and pagan philosophers, in the form of divine and secular texts. Bacon presented the process of the transmission of knowledge by way of an elaborate genealogy (OM I, vol. 3, 53f). He deemed it necessary to provide a comprehensive defense of wisdom together with the means by which it could be restored because he perceived his contemporaries to be limiting wisdom in scope and content, in fact to be corrupting it. The transmission of knowledge was unfolded imperfectly due to the sins of some philosophers.. The targets of Bacon’s critique very well may have been the Parisian “Artists,” some of whom understood the search for wisdom to be a purely theoretical and specialized endeavor, or Bacon’s own Minister General Bonaventure who condemned suspicious disciplines like experimental science and alchemy. Thus the scientific vision Bacon began to promote in the 1260s consisted of very detailed and specific normative reflections on the status of learning, for which he sought the support of Pope Clement IV.

b. The Critique of University Learning

The critique of university learning that Bacon developed in several of his writings encompassed philosophy as well as theology. According to Bacon, neither the philosophy nor theology of his time adequately embody the wisdom God revealed to humankind. On the contrary, in both philosophy and theology Bacon perceived numerous errors, lacunae, and forms of corruption. Thus he neither held back from denouncing them nor balked at accusing individual scholars of contributing to the demise of learning. In regard to the content of the curricula, for example, Bacon criticized the erroneous emphasis on logic and a particular kind of grammar and instead called for emphasis on rhetoric and the study of foreign languages. In several of his writings, most prominently in Opus Maius, Compendium Studii Philosophiae, and Compendium Studii Theologiae, he presented examples of ignorance, corruption, and error.

The scope of his critique of learning extended beyond the academy as well. Bacon drew connections between the state of affairs in the academy and the state of affairs in society because he did not regard these two spheres as separate but rather intimately connected. Bacon often stated that “by the light of wisdom the Church of God is governed, the republic of the faithful regulated, the conversion of infidels accomplished, and those who are obstinate in their malice, are more efficiently swayed toward the goals of the Church by the power of wisdom than by the shedding of Christian blood” (OM I, vol. 3, 1). Following from this, Bacon believed that the ultimate purpose of eradicating academic errors extended to the improvement of society. Bacon held that vain and useless academic practice was the cause of the ecclesiastic corruptions of pride, greed, and lust. In addition, Bacon did not spare worldly rulers from criticism (CSP, ch. 1, 398-400).

In his Opus Maius, Bacon pointed out four causes of error: (1) the example of unreliable and unsuited authorities, (2) the long duration of habit, (3) the opinion of the ignorant masses, and (4) the propensity of humans for disguising ignorance by the display of pseudo-wisdom. Bacon judged that all human evil is a result of these errors, and thus the reform that Bacon intended had to begin with reform in the educational institutions and the sciences. For example, Bacon identified one group of obstacles to wisdom in the practices of university teachers. The teachers wasted time and money on useless things and subjects because, instead of intellectual humility, they indulged in conformity and vanity (OM I, vol. 3, 2f). Thus scientific errors cast a long shadow, and the reform of learning was the only way by which to remedy society’s academic, social, and political troubles as they existed within the Christian community or even beyond it, in regard to the interactions with non-Christians such as Saracens or Jews.

c. Reform of Education

The reform program that Bacon proposed to Pope Clement IV was comprehensive in that it involved theology as well as most philosophical disciplines. Bacon revealed his depreciatory judgment of certain theological practices when in his Opus Minus he listed “the seven sins of the principal study which is theology” (OMi, 322). He included the “modern” practice of theologians introducing questions into theology that properly belong to the province of philosophy, such as questions about celestial bodies, matter and being, how the soul perceived through images or similitudes, and how souls and angels moved locally. In addition to questions of content, Bacon also found fault with the methods employed by modern theologians. For example, Bacon complained that questions about the sacraments or the Trinity were addressed using philosophical methods involving philosophical terminology, arguments and conceptual distinctions rather than using proper traditional Scriptural exegesis. Exegesis, on the other hand, suffered because of (1) the overemphasis placed on Peter Lombard’s (d. c.1160) Four Books of Sentences, (2) the deficient state of the Paris Vulgate, and (3) the neglect and ignorance of those sciences most useful for an accurate literal understanding of the text, which would advance exegesis according to the spiritual senses (OMi, 322-359).

Bacon proposed extensive reform measures to remedy these problems. He advised providing new translations of philosophical works and the Scriptures prepared by translators who were experts not only with regard to mastery of the respective languages but also the philosophical and theological material. Bacon called for an extensive modification of the curricula. He wanted to implement disciplines that were of real value to the progress of learning and that were not being studied properly at the time, like perspective (optics), experimental science, and alchemy. He also wanted to reform disciplines that, although being taught and studied, were studied with a wrong focus; here Bacon pointed to logic. For the use of the term progress in relation to Bacon see Molland, 1978, 567-571. For Bacon, studying logic was neither an end in itself nor the basis for the other sciences. On the contrary, Bacon held that logic is instrumentally valuable to theology and philosophy only insofar as it promotes understanding through semiotic and semantic analyses. It becomes superfluous when practiced as an inquiry into rules of argumentation. This was judged to be so because, according to Bacon, the knowledge of such rules is innate, which explains why logic does not provide scientists with special methodological principles or rules (OT, ch. xxviii, 102f). To counteract his contemporaries’ emphasis on logic, Bacon proposed to focus instead on mathematics. He believed neither philosophical nor theological matters could be properly understood without employing mathematics (OM IV, vol. 3, 175). Bacon’s reform program included the introduction of five main sciences that he thought were neglected or misunderstood by his contemporaries. Apart from mathematics, these were the science of languages, perspective, moral philosophy, experimental science, and alchemy. According to Bacon, these sciences were more conducive to the advancement of the mind, the body, and society than some of the sciences preferred by his contemporaries, such as logic, the less significant parts of natural philosophy, and a part of metaphysics. (OMi, 323f).

d. Human Happiness and the Sciences

Bacon’s later research in logic and languages, moral philosophy, and the natural sciences were fueled by his conviction that the spheres of scientific work and of everyday life were intimately connected. Bacon believed that the status of learning affects the quality of individuals’ lives in a variety of ways. After all, erroneous ideas or theories can yield harmful social consequences. Knowledge and learning are not private affairs but have a socio-political dimension. Thus he was persuaded that the sciences, both secular and divine, should serve human society as a whole in reaching happiness and salvation. He subsequently determined the respective rank of each science by the degree of its usefulness, that is, how much each of them contributed to human happiness. The theoretical sciences were thus subordinated to the practical goal of human happiness, as mentioned above. Since, according to Bacon, human happiness consists in salvation as understood by Christians, the highest science is Sacred doctrine or theology. Yet despite its formal supremacy, theology is still dependent on philosophy in that theology is incapable of accomplishing its goal without philosophy, that is, grammar, mathematics, experimental science, and moral philosophy (OM II, vol. 3, 36). In relation to theology, Bacon held moral philosophy to be the second highest discipline because it aims at salvation within the secular context of natural reason rather than revelation (MP I, §4, 4). In turn, Bacon held that the theoretical sciences, such as mathematics, are subordinate to moral philosophy. The goal of mathematics consists of explaining and describing the structure of the natural world, providing a kind of knowledge that contributes to practical ends only indirectly. Whereas, by contrast, the knowledge provided by moral philosophy is of immediate practical value.

According to Bacon, then, scientific research has an overall moral orientation, with both an emphasis on the afterlife and also an eye on practical worldly affairs. (CSP, ch. i, 395). The unifying purpose of all scientific study for Bacon is practical, which is why the practical sciences have priority over the theoretical. The practical value of a science is determined by the degree to which each science contributes to the improvement of human life. Improvements can be secondary, by technical innovation, or primary, by guiding the moral and spiritual life of humans, exhorting people to a virtuous and law-abiding practice that will ultimately be rewarded with eternal happiness: salvation in union with God.

3. Bacon on Language

Like many of his contemporaries, Roger Bacon attached great value to issues pertaining to the so-called Trivium. The Trivium, or the ‘three ways’ or ‘three roads’ of learning, was comprised of grammar, logic, and rhetoric. The Trivium constituted the trivial, that is, fundamental, part of the learning system, which consisted of the seven liberal arts, that was in place during late antiquity and much of medieval times. The remaining four arts, called the Quadrivium, were the mathematical disciplines: arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music.

Bacon’s study of language was broad, extending from semantics and semiotics to philology as well as to the socio-cultural question of the place of language studies within institutions of higher learning and society as a whole. Bacon’s study of speech and languages was not merely theoretical. His interest in understanding language, and his personal study of foreign languages like Hebrew and Greek,was motivated by his belief in the eminent practical importance of the study of speech and language. Bacon considered language mastery necessary for four purposes: (1) ecclesiastical functions, (2) the reform of knowledge, (3) the conversion of infidels, and (4) the battle against the Antichrist. Generally speaking, the goal of Bacon’s concern for languages was, in both his linguistic as well as his philological efforts, situated within the wider context of his intended reform of learning, aimed at the “Church and the Republic of the Faithful.” In addition, Bacon considered the knowledge of language, including an understanding of how words signify, an important prerequisite for any kind of philosophical or theological pursuit.

In Bacon’s work on linguistic and philological matters one can distinguish between two different stages. In the first stage, represented by the Summa grammatica, Summa de Sophismatibus et Distinctionibus, and Summulae Dialectices, we find Bacon’s contributions to the problem of universal quantification and to semantic problems revolving around the properties of terms. In particular, Bacon worked here on the problem of univocal appellation and predication in regards to what are called empty classes. Bacon’s solutions, especially to the semantic problems, provide the theoretical background against which he continued to develop his doctrines during the second stage of his work on logic and linguistic matters. In the second stage, represented by the De Signis and Compendium Studii Theologiae, Bacon worked on a theory of analogy, developed a theory of the imposition of signs, and, related to this, developed a view of the definition and classification of signs. The Compendium Studii Theologiae represents a later adjustment of the material brought forth in the De Signis. His work on philology stems largely from this later phase and is contained mainly in the Opus Tertium and Compendium Studii Philosophiae. He also wrote a Greek grammar, Oxford Greek Grammar, the first of its kind in the west and a work which he considered to be no more than an “introduction to the Greek language.” In these writings Bacon studied grammar insofar as it (1) pertained and contributed to the reading and speaking of languages and (2) contributed to an improvement of the methods and instruments of textual criticism.

Bacon’s views on logic and language included some unique claims and arguments. Bacon’s work on semantic problems—such as connotation and equivocation—was especially noteworthy. In his early work Summa de sophismatibus et distinctionibus, written in Paris, Bacon contributed to the debate on semantic information contained in ambiguous sentences. The theory of so-called natural sense, popular among some 13th century logicians, proposed that semantic information is grounded in the order in which terms are organized in a sentence. Bacon believed, however, that other aspects of communication must be considered. Sentence structure alone is not sufficient to decode the semantic information contained in a sentence. He challenged the theory of natural sense in his doctrine of the “generation of speech” by emphasizing the relation between the intention of the speaker, linguistic form, and interpretation of the hearer in the context of understanding meaning. In short, understanding semantic information is, for him, a matter of interpretation. Another important claim of Bacon’s, which connects the early Summulae dialectices with the later De signis, relates to the question of whether terms can univocally signify existent and nonexistent, or universal and particular entities. For Bacon, terms like Caesar or Christ signify presently existing entities only and signify equivocally when predicated of a dead person. This semantic position, which would classify Bacon today as a semantic externalist, put Bacon in opposition to a number of his contemporaries, most famously Richard of Cornwall.

In addition to semantics, Bacon also did important work in semiotics and signification and developed views which in some cases were radically different from 13th century mainstream opinion. He challenged a number of common tenets on the nature of signs. Bacon worked within the Augustinian framework, according to which signs are in the category of relation, and emphasized that signification is a three-term relation. A sign, take a word for example, is a sign of something to some interpreter. More specifically, Bacon’s theory of signs stressed the “pragmatic” relation of the sign to the interpreter and thus underscored the context in which a sign is situated instead of the sign’s relation to the significate, as was the commonly held opinion. Another important element in his work in semantics is his analysis of imposition, that is, the act of name-giving. He distinguishes between two modes of imposition: (1) the very first imposition by the first name-giver and (2) subsequently applying a name to something different than what the name signifies according to its first imposition. Bacon thought of the very first imposition as an act similar to baptism. He understood it in terms of a situation in which a word is chosen as a label for a present thing. After which, the thing is called by that name. In other words, the first imposition is the act by which a human name-giver decides to use a sound to refer to a thing and thereby endows that sound with meaning, and a word is created. However, according to Bacon, speakers have the power to change the meaning of words in situations in which they need to express something they currently lack a word for or in which the particular thing which the word originally named ceases to exist. Bacon argued that the use of a word is not restricted to the meaning endowed to it during the first act of imposition. On the contrary, a speaker may apply a word to any other object, thereby imposing a new meaning and making the term equivocal. The term’s interpretation then depends on the speaker’s intention. Bacon believed that these kinds of modifications of meanings of words occur tacitly and constantly and sometimes even without people being conscious of it. Bacon considers metaphors as a prevalent example of second imposition. In addition, Bacon also developed a comprehensive classification of signs or modes of signification, into which he integrated substantial semantic analyses. According to Bacon’s notion of signification, as part of his theory of imposition, signs immediately signify the things themselves rather than mental concepts or representations of things in the mind of the speaker.

4. Mathematics and Natural Sciences

a. General Remarks

Among Roger Bacon’s most widely known contributions to philosophy are his reflections and arguments pertaining to the fields of mathematics and the natural sciences. Within the latter, Bacon is especially known for his emphasis on experience and on experimental science (scientia experimentalis), including optics, also called perspective (perspectiva or scientia de aspectibus). Many of his reflections on the physical world were presented in the context of his extensive critique of university learning dating from the 1260s, which oftentimes lent a rhetorical and pedagogical tenor. However, Bacon’s contributions to this field were not restricted to polemics. Apart from the papal opera (Opus Maius, Opus Minus, and Opus Tertium), his most important works on mathematical and physical topics were the De Multiplicatione Specierum (‘On the Multiplication of Species’; dated prior to the papal opera), the Communia Naturalium, and the Communia Mathematica, both dated after 1267.

Bacon’s accomplishments in these fields do not consist of reports of concrete scientific practice or specific methodological guidance in experimentation. On the whole, his work in mathematics and the natural sciences was more theoretical. He defended noteworthy pedagogical and methodological insights pertaining to the mathematization of natural philosophy for example. He also made the somewhat successful effort to reconcile the disparate Platonic and Aristotelian scientific approaches and thereby present a practicable and convincing synthesis (Fisher and Unguru, 1971, 375; Lindberg, 1979, 268).

i. Bacon’s Modification of the Quadrivium

In the Latin medieval tradition, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy were subsumed into the Quadrivium. Together with the so-called Trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric), they formed the two parts of the seven liberal arts (septem artes liberales). At the time the seven liberal arts were considered to be branches of philosophy. All of the quadrivial or mathematical arts dealt with quantity, the principle according to which things were said to be equal or unequal. Arithmetic and music dealt with discrete quantities, or numbers, whereas geometry and astronomy dealt with continuous quantities, such as lines. Traditionally, the mathematical or quadrivial disciplines constituted the medieval “scientific syllabus” in that they studied the natural world. Under the metaphysical assumption that every physical entity was formed through the essence of number and that physical phenomena could thus be “broken down” into arithmetical or geometrical terms, the natural world could be described using the quadrivial disciplines. Astronomy, for example, studied the motion of celestial bodies by employing numerical calculation and geometry.

Bacon’s concern for the quadrivial disciplines was ultimately ethical. By procuring the Pope’s support for a reform of liberal arts studies, he hoped to improve student learning and to boost scientific progress, which would ultimately serve the development of moral persons. (For the use of the term progress in regard to Bacon see Molland 1978.) For this purpose, Bacon modified the inherited division by adding new sciences to the traditional four. He identified a list of seven “special sciences,” among which he included perspective (optics), judicial astronomy (astrology), the science of weights, medicine, experimental science, alchemy, and agriculture. Bacon held that three of these sciences are especially important: judicial astronomy, alchemy, and experimental science (CN, I, 5). Yet, beyond just listing sciences worthy of study, Bacon made the case for new ways in which to approach some of the more established sciences, thereby introducing hitherto less known or neglected sources. In the case of perspective, for example, he advocated the use of Alhazen’s (al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham) De Aspectibus, or Perspectiva.

Bacon considered his contemporaries’ neglect of these “special sciences” to have detrimental consequences not only for the progress of learning but for the state of society as a whole. He reproached teachers and scholars of medicine for approaching their field in the wrong way because they neglected mathematics and experimentation. He scolded theologians for ignoring the “greater sciences” in their study of the Scriptures. Bacon thought a reform of liberal arts studies in general, and the Quadrivium in particular, was imperative because of the eminent utility of the mathematical and natural sciences. An improved understanding of the natural world would benefit Scriptural hermeneutics in that an understanding of the Scriptures’ literal sense would lead to an improved understanding of their spiritual sense. Bacon believed his reforms would also foster a practical operative knowledge capable of alleviating all sorts of human ailments or of ensuring Christians’ supremacy in warfare. Although dissatisfaction with the status quo of teaching and research constituted much of Bacon’s apology of the sciences, he also presented original material on scientific method, in Scientia Experimentalis for example, as well as original scientific content, like in his doctrine of physical causation.

ii. Bacon’s Scientific Views and the Condemnation of 1277

In advocating the “special sciences,” Bacon was concerned with the intellectual climate in which he found himself. The climate in Paris prior to Bishop Étienne Tempier’s issuance of a condemnation in 1277 was that of suspicion against Bacon’s most favored sciences: judicial astronomy, alchemy, and experimental science. With regard to the atmosphere in the Franciscan order, it is possible that Bonaventure, Bacon’s superior, partly had Bacon in mind when in his Collationes (1273) he accused “Aristotelian” philosophy of being at odds with Christian dogma. Thus much of Bacon’s presentation of, for example, judicial astrology and celestial influence was informed by wariness. He did not want to be charged with necessitarianism, the view that celestial events determine worldly events;among the doctrines impugned by Bishop Tempier was astrological determinism. In the context of alchemy and experimental science Bacon heeded the danger of being denounced for magic (OM IV, vol. 1, 137-139). However, Bacon was an outspoken supporter of natural magic, and he accused his opponents of “infinite stupidity” and deserving of being ridiculed as asses (asini) for ignoring the utility and benefits of judicial astronomy (OT, ch. lxv, 270). To forestall possible objections and charges, Bacon went to great lengths to distinguish magic proper, doctrines and practices accomplished with the help of demons, from “natural magic,” wondrous and awe-inspiring physical phenomena. He defended the respective sciences by naturalizing them. He provided arguments showing that seemingly magical effects imitate nature in their operations and do not use the aid of demons. One very important element in Bacon’s naturalistic explanation of supposedly magical phenomena, like astrological influence, was his theory of physical causation, best known as the multiplication of species (multiplicatio specierum, discussed further below). For Bacon’s view on magic see Molland 1974.

It is commonly agreed, however, that in certain respects Bacon’s views bordered on magical traditions. This is evident from his text De Secretis Operibus Artis et Naturae (‘On the Secret Works of Art and Nature,’ c. 1267) as well as from the third prerogative of experimental science in which Bacon’s imagination ran wild, projecting marvels like ever-burning lamps. These writings were kindled by the desire to benefit State and Church (OM VI, vol. 2, 217).

b. The Nature and Value of Mathematics

Secondary literature is not entirely favorable towards Bacon’s achievements in mathematics. It is commonly agreed that Bacon was not a creative mathematician. Yet it is also widely recognized that Bacon was well read and had a solid comprehension of the standard sources of 13th century mathematics. Bacon’s originality was more “in his thoughts about mathematics” rather than in his theoretical innovations (Fisher and Unguru, 1971, 355).

i. The Object and Division of Mathematics

Bacon adopted an Aristotelian abstractionist view of the objects of mathematical inquiry. Mathematics is the science dealing with objects whose principle was quantity. The form of quantity, though, had to be abstracted from motion and corporeal matter before it could be investigated by arithmetic or geometry. Although quantity exists in matter, in mathematics quantity is considered as abstracted from matter and motion. Bacon insisted, however, that in this abstracting procedure the imagination does not run the risk of positing quantity to exist by itself, in the manner of a Platonic form. That would defeat the purpose of mathematical inquiry, which is performed for utilitarian reasons, specifically for the sake of “corporeal quantity,” not for the sake of quantity itself (CM, 59).

One element that stands out in Bacon’s reflections about mathematics has to do with the division of the mathematical sciences, mainly presented in the third distinction of his Communia Mathematica. For pedagogical purposes, Bacon thought it important to distinguish between two principal branches of mathematical study. One branch deals with the universal themes of mathematics in terms of its “elements and roots;” this first branch can be termed common mathematics. The second branch deals with the specialized domains of geometry, arithmetic, music, and astronomy.

The second principal branch of mathematics is divided into two main parts: a speculative and a practical part. Following from this, each of the proper mathematical sciences can be seen, according to Bacon, to have a speculative as well as a practical side. For example, while the speculative part of geometry considers contiguous quantity removed from any practical concerns, the practical part of geometry applies geometrical insights to operational, concrete interests (CM, 38f) In either case, speculation must precede practice, which meant that Bacon considered mathematical theory to be subjugated to technological practice.

The postulation of “common mathematics” is considered to be the most original element of Bacon’s division of mathematics. In this context, Bacon leveled a critique of Euclid’s Elements, despite the fact that he believed Euclid was an important authority in the history of mathematics. Again, for Bacon, mathematics is the science dealing with quantity. The different specialized parts of mathematics deal with different kinds of quantity. Arithmetic and music deal with discrete quantities such as numbers. Geometry and astronomy deal with continuous quantities such as lines. The concept of quantity in general, however, could not be fully understood without a comprehension of the meaning of related concepts such as finite, infinite, position, and contiguous. Bacon criticized Euclid for being oblivious to a thorough treatment of these concepts. Such a treatment could be made by separating out a realm of common mathematics, which deals with quantity in general, and could be expressed by basic principles common to all mathematics (Molland, 1997, 165-168).

ii. The Methodological Relevance of Mathematics

Bacon’s favorite maxim in scientific matters consisted in emphasizing the utility of each science. As we have seen, this lead him to subjugate scientific research to the spiritual and concrete practical needs and interests of human beings. Since, for Bacon, the utility of a science is linked to its end, the end informs choices of content and form for each science. In other words, it did not only matter what was studied, but also how the results of those studies were presented to those needing instruction. In this respect, mathematics is no exception. A considerable part of Bacon’s reflections on mathematics were characterized by this “utilitarian” approach. It is not surprising, then, that Bacon considered mathematics to have no intrinsic value. According to Bacon, the mathematical disciplines (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy) are of solely instrumental value. Doing mathematics should by no means be a purely theoretical inquiry. Yet, while emphasizing Bacon’s conviction that mathematics has no intrinsic value, it should not be overlooked that Bacon regarded mathematical study as instrumentally good for all the other sciences, including theology. Indeed, almost the whole of the fourth part of the Opus Maius is devoted to the presentation of the utility of mathematics in matters secular and divine.

According to Bacon, mathematics is “the gate and key” to the other sciences. Bacon regarded the comprehension of mathematical truth as being among the first steps in the order of cognition because “it is, so to speak, innate in us.” Mathematical objects by their very nature “are more knowable by us,” therefore, it is with these objects that our learning should commence (OM IV, vol. 1, 103-105). Indeed, Bacon went on to claim that a scientist who is ignorant of mathematics cannot have certain knowledge of either the other sciences or worldly matters. Mathematics, Bacon stressed, trained the mind for future study and raised the degree of knowledge acquired by the mind to the level of certainty (OM IV, vol. 1, 97). In other words, in order to practice the other sciences with a proper level of sophistication, or at all, mathematics is required. If the scientist’s goal is to truly understand the physical world, then she had to employ mathematics. This means that although mathematics is epistemologically vital to the progress of other sciences, it is not their queen in terms of dictating ends. In the order of learning, mathematics is ranked on the lower end (Molland, 1997, 164).

When Bacon stated that scientific study seeks to attain truths about the world, the term truth connotes a kind of knowledge in virtue. The human mind becomes peaceful in its scientific quest (ut quiescat animus in intuitu veritatis). To reach this state requires sense-based experience that brings the truth of scientific conclusions face-to-face with the scientist. In Bacon’s view, mathematics as well is subject to the general rule that the empirical dimension is essential to proper knowledge. For example, for a student to fully grasp the proof of the Euclidian equilateral triangle, she needs to see it actually being constructed (OM VI, vol. 2, 168). However, it is not simply the case that mathematics requires a verification of its conclusions through the aid of experiencing, as if this kind of experience were external to mathematical procedure. The reason why mathematical procedures are a guarantor for scientific certainty, according to Bacon, lies exactly in the fact that sense experience is an integral part of it. In mathematics there are necessary demonstrations that, because proceeding by way of necessary cause, achieve full and certain truth without error. In addition mathematics contains certifying experience as an intrinsic component of its basic operations, insofar as it has examples and tests that can be perceived by the senses, such as drawing figures or counting (OM IV, vol. 1, 105f). Thus, for Bacon, in order for the human mind tograsp the truth, it requires freedom from error and doubt, both of which mathematics is able to provide because of its connection to experience. The certifying potential of experience was further developed by Bacon in the sixth part of the Opus Maius, under the name of the first dignity of experimental science (prima prerogativa) (Fisher and Unguru, 1971).

iii. The Physical Relevance of Mathematics

Bacon can be regarded as having been among the first scholars to emphasize the physical relevance of mathematics. Bacon’s rationale for emphasizing the physical relevance of mathematics has epistemic elements, as discussed above, but it also has metaphysical elements, which have to do with the way in which Bacon conceived the structure of the physical world.

Everything that exists in nature, Bacon stated, was brought into existence by two causes, the efficient and the material cause. Every efficient cause, however,

acts through its own force which it produces in the matter subject to it, like the light of the sun produces its force in the air which is the light which is spread out throughout the world from the light of the sun. And this force is called likeness, image, species, and many other names, and this [force] produces substance as well as accident, both spiritual and corporeal […] Thus, agents’ forces like these bring about every operation in this world […] (OM IV, vol. 1, 111).

To understand physical agency brought about by efficient causes, however, requires mathematics because physical operations occur by means of forces, or species, like light, which operates through rays. Not only physical agency but psychic and astrological agency require mathematics as well to understand. For Bacon, light is an instance of physical agency through forces or species following the geometrical rules of reflection and refraction. It is a privileged case of such agency because of its visibility. Herein also lay the reason why the science of light and vision (perspective) is embedded in the theory of the multiplication of species. If a natural philosopher wants to explain natural processes, she must focus on lines of physical action and employ mathematical methods. Natural philosophy must follow the principle of motion and rest, which involves instances of change and species following geometrical principles (OM IV, vol. 1, 110).

c. Bacon’s Theory of Physical Causation and Perspective

Bacon’s treatises De Multiplicatione Specierum and Perspectiva, comprising the fifth part of the Opus Maius, represent his scientific work at its best. Although Bacon was well-read on all of the new sciences presented in the course of the Latin medieval translation movement, he was most accomplished in the fields of light, vision, and the universal emanation of force. However, the actual extent of his accomplishments in this field has been the subject of a good deal of debate. Both the De Multiplicatione Specierum and the Perspectiva are available in modern critical editions and accompanied by English translations, prepared by David C. Lindberg.

In developing an account of physical causation in his doctrine of the multiplication of species, Bacon stood in a long tradition of philosophical and biblical writers who used light metaphors in different epistemological, metaphysical, and physical contexts. Although unknown during the Middle Ages, Plotinus’ doctrine of emanation—with its physical consequence that all beings radiate likenesses of themselves—had an indirect influence on Bacon’s physical doctrine of the multiplication of species, a physical doctrine of emanation, so to speak (Lindberg 1983, xxxix-xlii). The channels through which Plotinian and Neoplatonic ideas reached Bacon included Augustine, Arabic sources such as al-Kindī’s (d. c. 873) De Radiis and De Aspectibus, Avicebron’s (d. c. 1058) Fons Vitae and the Book of Causes (Liber de Causis) transmitting ideas from Proclus’ Elements of Theology. Next to the newly translated Aristotelian works, other important sources for Bacon’s doctrine of physical causation were treatises on more technical subjects such as Euclid’s Optica, Ptolemy’s Optica, and Alhazen’s De Aspectibus.

Among the first scholars to embrace this body of knowledge was Robert Grosseteste, whose influence on Bacon has been much debated. For Grosseteste’s influence on Bacon see Hackett, 1995 and 1997a. In any case, crucial for both Grosseteste and Bacon in their physical and metaphysical considerations was al-Kindī’s notion that “every creature in the universe is a source of radiation and the universe itself a vast network of forces” (Lindberg, 1983, xlv). In al-Kindī, both Grosseteste and Bacon found a mathematical and physical analysis of the radiation of force, or physical agency, following the rules of geometrical optics. According to this analysis rays of light spread out by rectilinear propagation, reflection, and refraction. In a similar manner, the radiation of other kinds of species could also be understood along optico-geometrical lines. In comparison to al-Kindī and Grosseteste, Bacon’s achievement consisted in the naturalization of Grosseteste’s physics of light, “itself an outgrowth of al-Kindī’s universal radiation of force.” Bacon took Grosseteste’s doctrine out of its metaphysical and cosmogonical context and modified it to become a doctrine of physical causation (Lindberg, 1983, liv). In other words, in the De Multiplicatione Specierum Bacon brought forth a doctrine with which he was able to explain all kinds of physical causation—optical, astrological, and psychic—and to answer the question of how one physical object was able to affect another physical object even if they are not contiguous.

In Bacon’s view, the technical term species was not to be confused with Porphyry’s universal species . The former denotes the likeness or similitude of any naturally-acting thing, or its “first effect, ” as he called it (DMS, 2). What this implies is that a substance or quality is able to affect its surroundings by sending forth a likeness of itself in all directions unless obstructed—an activity which makes recipients of their likeness like themselves. By this process, natural agents impact others by means of forces bearing the specific nature of the original agent. Yet, this process of causation takes place without the original agent emitting something since this would result in its corruption, a possibility which Bacon excludes. Bacon emphasizes that instead of comprehending the process of the production of species in terms of emission or material emanation, as the ancient atomists did, it should be understood in terms of a transmission “through a natural alteration and bringing out of the potentiality of the matter of the recipient” (DMS, 45). For the physical nature of the species, this meant that they were generated in the recipient matter by a “bringing forth” (eductio), an elicitation “out of the recipient’s matter active potentiality” that already exists there (DMS, 47). In cases in which the agent and the recipient are contiguous, “the active substance of the agent, touching the substance of the recipient without intermediary, can alter, by its active virtue and power, the first part of the recipient it touches. And this action flows into the interior of that part, since the part is not a surface, but a body” (DMS, 52f). In cases in which this “bringing forth” could not be continuous because the agent and the effect are not contiguous, it occurs in a stepwise manner through a medium. In those cases, natural causation takes place in the form of successive generation or multiplication of species along straight or direct, reflected, refracted, twisting, or accidental lines. The species are multiplied step by step, beginning in a small section of a medium contiguous with the original agent, from whence it draws out its likeness in the next adjacent part, and so forth, until finally the last part of the medium ultimately superimposes the nature of the agent on the recipient. In the Perspectiva, the fifth part of the Opus maius, Bacon applied his doctrine of the multiplication of species to the subjects of the propagation of light and vision. Although much of Bacon’s account of vision was borrowed from Alhazen and other predecessors, Bacon synthesized that account into a form that became historically important. Indeed, it remained the standard account of visual theory until the work of Johannes Kepler (d. 1630) (Lindberg, 1997, 265).

In developing his doctrine of natural agency, Bacon drew principally on the optical tradition because he regarded light, acting by means of rays, as a paradigmatic case of physical causation. In fact, he thought of light as a privileged case because of its visibility—the radiation of force being like the sun (OM IV, vol. 1, 111). Inspired by Aristotle, Bacon stated that we know everything through vision, and perspective is the science of vision by means of which one can understand the structure and laws of the universe (OT, chapt. xi, 36f.). Perspective became Bacon’s model science for physical causation and was, compared to all the other sciences, especially significant for human understanding of the world. According to Bacon, because the radiation of light follows the geometrical principles of rectilinear propagation, reflection, and refraction, it employs mathematical methods and involves the possibility of geometrical demonstration, what Bacon considered an “experiment”; moreover, it is a subdivision of mathematics. As far as Bacon’s accomplishments in this field are concerned, it is commonly agreed that he was one of the leading Western proponents of the doctrine of the multiplication of species. It was Bacon, “more than any other author in the Latin world, who taught Europeans how to think about light, vision, and the emanation of force ” (Lindberg, 1997, 244).

d. Experimental Science

Following Aristotle, Bacon held that “all humans by nature desire to know” and are naturally drawn towards the beauty of wisdom and carried away by their love for it. Bacon emphasized that to ensure success in learning, it is necessary to first inquire into the method best suited for it, as there are better and worse ways to proceed in the sciences. In his Compendium Studii Philosophiae (CSP), Bacon distinguished between three ways of acquiring knowledge—knowledge through authority, reason, and experience—and he made it clear that not all three ways are of equal value. Neither authority nor reason are sufficient for knowledge because reliance on authority alone yielded belief but not understanding, while reason alone could not distinguish between true sentences and sentences having only the appearance of knowledge (CSP, ch. i, 396f). According to Bacon, achieving knowledge requires three things: (1) to heed the structure of the scientific material and to begin with what is first, easier, and more general then proceed to what is later, more difficult, and more particular, (2) to proceed using the clearest possible words without causing confusion, and (3) to reach a level of certainty that leaves behind all doubt. For this, Bacon considered it crucial to employ experience, and, in regard to the order of learning, to precede experience with mathematics. Thus, the only way for the human mind to arrive at the full truth, and to rest in the contemplation of truth, is through experience, a subjective comprehension based on sense perception. Bacon believed that experimental science (scientia experimentalis) was virtually unknown to the “rank and file of students;” thus he thought it necessary to present to the Pope its “powers and properties.” Bacon thus laid out his theory of experiential knowledge in the sixth part of Opus Maius, presenting scientia experimentalis as the penultimate science, second only to moral philosophy (OM VI, vol. 2, 172).

Many of Bacon’s writings bear witness to his concern not only for the content of knowledge (that is, the available material), but also the quality of the knowledge acquired (ideally, conclusions should be held in a manner that penetrates and reassures the soul and leaves it in a state of certainty and free of doubt). Thus, when Bacon said that “[…] nothing can be sufficiently known without experience,” he meant to emphasize the role that individual sense perception (and especially vision) plays in the process of learning. (OM VI, vol. 2, 167) For Bacon, learning denotes not only the process of the acquisition of knowledge, but also the process of the restoration of wisdom that was given by God at the beginning of time and subsequently lost through sin (see Section 2a). Therefore, experiential knowledge is of fundamental importance in Bacon’s project of the reform of studies. Its importance and utility extended far beyond the theoretical sphere, encompassing progress in applied science and technology, and ideally leading to broad improvements in both Church and State.

i. Experience and Experiment

The meaning of the Latin term experimentum is ‘test’ or ‘trial.’ Bacon used this term to cover a variety of testing practices, such as first-hand and second-hand sensory experience and the inner, spiritual experience of divine illumination. Experimentum also was used to refer to various kinds of practical knowledge that are more or less connected to empirical practice. The notion of experience or experiments as a basis for induction, that is, for inferences based on observation, was familiar to Bacon, but in the context of advancing scientific understanding he did not seem to attach much importance to it. In his attempts to discover the cause of the rainbow, however, there are some inductive elements (Fisher and Unguru, 1971, 376).

In his concept of scientia experimentalis, Bacon did not only consider experience through external senses, through vision, for example. His understanding was firmly grounded within the Augustinian tradition in affirming another kind of experience next to those provided by the external senses. Experience that consists in “internal illumination” (OM VI, vol. 2, 169). For Bacon, experience through the external senses does not completely suffice to provide certainty in regard to physical bodies, “because of its difficulty,” and it does not achieve anything in the realm of spiritual things. The ancient patriarchs and prophets received their scientific knowledge by way of this divinely granted internal illumination. Thus, experience-based knowledge according to Bacon was twofold: philosophical and divine. The philosophical was rooted in external senses and the divine was rooted in divine inspiration occurring internally (OM VI, vol. 2, 169-172).

ii. The Three Prerogatives of Experimental Science

The goal of the major section of the sixth part of the Opus Maius was to outline the different dimensions of the value and utility of scientia experimentalis. In his theory, Bacon explicitly and carefully distinguished three different “prerogatives” or functions of scientia experimentalis, each producing its own peculiar result. Bacon’s usage of the name scientia experimentalis referred not to one but to three different things, each being useful for the restoration of learning, yet in different ways. Scientia experimentalis was both an instrument used within other sciences like mathematics or alchemy and a science in its own right. Scientia experimentalis experientially confirms or refutes the theoretical conclusions of other sciences, first dignity; it provides observations and instruments needed for empirical practice, second dignity, and it actively investigates the secrets of nature, third dignity. Modernly speaking one can say that by dividing scientia experimentalis into three dignities, Bacon acknowledged the difference that exists between science and technology.

The first prerogative or dignity of scientia experimentalis, according to Bacon, was aimed at the conclusions of the other sciences (OM VI, vol. 2, 172-201). With this dignity, Bacon’s goal was not to render conclusions logically consistent with one another, but rather experientially test or challenge theoretical claims to knowledge and thereby aid in the process of attaining doubt-free, certain knowledge. . Thus, in its first dignity, scientia experimentalis puts universal theoretical claims to the test by confronting them with the actual experiential objects. It thereby completes science’s search for truth and certitude. Certitude, in turn, is a function of the way by which knowledge is acquired and describes the state in which the human mind has a direct intuition of an experiential object. According to Bacon, this dignity of scientia experimentalis also includes mathematical conclusions, which cannot be fully known based on demonstrations alone since they lack reference to concrete experiential particulars. In his discussion of the rainbow and the halo in the sixth part of Opus Maius, Bacon gave a detailed illustration of this function of scientia experimentalis. In particular, by referring to observation and the application of the laws of perspective, Bacon attempted to provide a causal account of the appearance of the rainbow (Lindberg, 1966; Hackett, 1997b, 285-306).

The second prerogative also situates scientia experimentalis as an instrument within the other sciences. Yet it is not related to experience as a source of knowledge or certitude as described in the first dignity. In its second function, experimental knowledge serves the purpose of developing the other speculative sciences to their fullest potential by venturing into the unknown and the occult through experimental practice involving instruments. Scientia experimentalis, for Bacon, becomes a tool utilized in the other sciences through its ability to discover truths hidden in these sciences—truths whose unearthing went beyond the competence of those sciences. For example, although human life and health belong to the science of medicine, scientia experimentalis goes beyond the field of medicine by seeking out means by which to prolong life (OM VI, vol. 2, 202).

In the third prerogative Bacon gave scientia experimentalis the status of a science within its own right, independent of the other sciences. Experimental science investigates the secrets of nature by its own power. Its function includes the acquisition of knowledge of the future, past, and present in which it even exceeds astrology, and the accomplishment of marvelous works such as the manufacturing of antidotes against animal poisons or technologies that could be used in warfare. (OM VI, vol. 2, 215-219)

iii. Bacon as Experimenter

In many respects, Bacon’s experimental practice was not as sophisticated and strategic as his theory of scientia experimentalis. It is the general verdict arrived at by scholars that Bacon did not live up to his promise of the application of experimental methods. Bacon’s accomplishment as experimenter has been criticized for many reasons including his silence on the concrete question of how to conduct the experiments in practice outlined by him in theory. In regard to perspective, it has been pointed out that while Bacon’s theories were not primarily the result of his own experimental practice, he still engaged in some experimental practice that went beyond simple, everyday observation, like in the case of the rainbow where he performed more complex observations. These observations have been described as “geometrical tests” (Lindberg, 1997, 268-271). Bacon’s experimental practice also encompassed observations that were supposed to supply empirical data requiring explanations in the context of existing theories, for example when employing the rules of refraction to explain the rod that appears bent upon partially being submerged in water. The most usual function of experiment and experience, though, consisted in the verification of theoretical claims made by the other speculative sciences.

e. Alchemy and Medicine

Apart from experimental science, the other science in which Bacon’s practical, secular concerns became manifest was alchemy—the science of the “generation of things” from the four elements. Unsurprisingly, alchemy occupies a very high position in Bacon’s reform of studies. He presented his “alchemical manifesto” (Newman, 1997, 319) as part of the Opus Tertium and at the end of the Opus Minus (OT, ch. xii, 39-43; OMi, 359-389). Apart from the papal opera, there were in addition a few other works dealing with alchemical-medical questions, such as the De Erroribus Medicorum and the Liber Sex Scientiarum in 3° Gradu Sapientie. In Bacon’s judgment, alchemy needed an advocate because natural philosophers and the common run of students were ignorant of the true potential of alchemy. Due to the interconnectedness of the sciences, ignorance of alchemy was to the detriment of speculative and practical medicine, which in turn affected the very general state of human affairs. For Bacon’s views on alchemy see Newman 1997.

Because alchemy was on the blacklist of ecclesiastical authorities, it was necessary for Bacon to carefully qualify his understanding of alchemy and to thoroughly differentiate it from magic. Bacon attempted to do this in his Epistola de Secretis Operibus Artis et Naturae, et de Nullitate Magiae. Against magical practices that relied on the help of evil demons, Bacon argued that alchemy relied on the powers of science, which operated in accordance with nature by artificially employing and directing the potential latent in nature. Bacon argued that the powers of the sciences even surpassed those of nature when in their practice they used natural powers as their instruments. In effect Bacon claimed that alchemical theory would provide the necessary naturalization of seemingly magical natural processes (Epistola de Secretis Operibus, 523).

As was common for his approach in organizing the sciences, Bacon divided alchemy into two branches, one speculative and the other practical. Speculative alchemy teaches the generation of things from the four elements (fire, air, water, and earth). What arises from the elements, Bacon argued, are things like metals, salts, or precious stones, and two types of humors: the “simple” humors (blood, phlegm, and black and yellow bile) and the “compound” humors of the same names. Practical alchemy, on the other hand, applies those theoretical insights for the purposes of, say, manufacturing various items of chemical technology like precious metals or pigments (OT, ch. xii, 40).

The notion that the interplay of the humors directs human vital processes and that the alchemist has the ability to analyze and transmute material substances, based on the belief in the transmutability of the proportions of humors, lead Bacon to call for practical action. He wanted the so-called philosophers’ stone and the universal remedy, Panacea, to be produced with alchemy. In general, he thought alchemy should be applied to medicine, which, during his time, was a “significant novelty” (Newman, 1997, 335). In the course of his alchemical work, Bacon assigned two roles to alchemy in medicine. The first role consisted in purifying ordinary pharmaceuticals, and the second role concerned prolonging human life to its utmost. Bacon believed that the shortness of people’s lives during his time was due not to divine plan, but to bad health regimens. Over time, these regimes had corrupted human complexion. Because this corruption arose from natural causes it was susceptible to natural remedies that would help to reestablish “equal complexion,” that is, a state of incorruptibility where the elemental qualities of a substance existed in perfect harmony according to their virtue and active power. In Bacon’s mind, nature, with the help of alchemy, could produce the same result by applying appropriate means.

The secular trajectory of Bacon’s reductio artium and his “utilitarian” scientific outlook emerged in the most pronounced form in Bacon’s work in medical alchemy. Even though Bacon’s attempt to combine alchemy and medicine under the aegis of experimental science did not have a major impact on his contemporaries, “it did at least foreshadow the development of a medical alchemy in the following century” (Newman, 1997, 335).

5. Moral Philosophy

a. General Scope and Nature of Bacon’s Moral Philosophy

Roger Bacon presented his main thoughts and arguments on morality and human moral agency in a piece entitled Moralis Philosophia (MP), which formed the seventh and last part of the Opus Maius (1266–1268). As such, the Moralis Philosophia marked the culmination of Bacon’s proposals on the reform of the studies of language and the sciences commissioned by Pope Clement IV. The Moralis Philosophia is available in a modern critical edition prepared by Eugenio Massa (1953). A short résumé of the main elements of Bacon’s moral philosophy is contained in the Opus Tertium, chapters xiv, xv, and lxxv.

i. Morality and Happiness

Generally speaking, Bacon’s moral reflections were built on the assumption that the end or goal of human life (finis hominis) is happiness and that human moral practice in the form of virtuous agency is a decisive factor in humans’ attainment of happiness. For a human being, the proper way to live is in a human manner and, as Bacon said, “virtue is the life of a human being” (MP III, §§1-4, 50f). Bacon understood happiness to be synonymous with salvation and believed philosophy and faith are both indispensable for its attainment. On the nature of happiness, true philosophy and the principles of Christian faith are in complete agreement. Thus the topic around which Bacon’s main practical and normative concerns in moral philosophy revolved was human moral agency. This took three specific forms: (1) human moral practice in relation to God, (2) human moral practice in relation to one’s neighbor in the form of social relations, and (3) human moral practice in relation to persons themselves in the form of virtue or vice. Bacon’s moral philosophy was normative in the sense that it concretely prescribed the details of these relations, and practical in the sense that it exhorted agents to live according to these moral principles and laws (MP I, §4, 4).