Simplicity in the Philosophy of Science

The view that simplicity is a virtue in scientific theories and that, other things being equal, simpler theories should be preferred to more complex ones has been widely advocated in the history of science and philosophy, and it remains widely held by modern scientists and philosophers of science. It often goes by the name of “Ockham’s Razor.” The claim is that simplicity ought to be one of the key criteria for evaluating and choosing between rival theories, alongside criteria such as consistency with the data and coherence with accepted background theories. Simplicity, in this sense, is often understood ontologically, in terms of how simple a theory represents nature as being—for example, a theory might be said to be simpler than another if it posits the existence of fewer entities, causes, or processes in nature in order to account for the empirical data. However, simplicity can also been understood in terms of various features of how theories go about explaining nature—for example, a theory might be said to be simpler than another if it contains fewer adjustable parameters, if it invokes fewer extraneous assumptions, or if it provides a more unified explanation of the data.

Preferences for simpler theories are widely thought to have played a central role in many important episodes in the history of science. Simplicity considerations are also regarded as integral to many of the standard methods that scientists use for inferring hypotheses from empirical data, the most of common illustration of this being the practice of curve-fitting. Indeed, some philosophers have argued that a systematic bias towards simpler theories and hypotheses is a fundamental component of inductive reasoning quite generally.

However, though the legitimacy of choosing between rival scientific theories on grounds of simplicity is frequently taken for granted, or viewed as self-evident, this practice raises a number of very difficult philosophical problems. A common concern is that notions of simplicity appear vague, and judgments about the relative simplicity of particular theories appear irredeemably subjective. Thus, one problem is to explain more precisely what it is for theories to be simpler than others and how, if at all, the relative simplicity of theories can be objectively measured. In addition, even if we can get clearer about what simplicity is and how it is to be measured, there remains the problem of explaining what justification, if any, can be provided for choosing between rival scientific theories on grounds of simplicity. For instance, do we have any reason for thinking that simpler theories are more likely to be true?

This article provides an overview of the debate over simplicity in the philosophy of science. Section 1 illustrates the putative role of simplicity considerations in scientific methodology, outlining some common views of scientists on this issue, different formulations of Ockham’s Razor, and some commonly cited examples of simplicity at work in the history and current practice of science. Section 2 highlights the wider significance of the philosophical issues surrounding simplicity for central controversies in the philosophy of science and epistemology. Section 3 outlines the challenges facing the project of trying to precisely define and measure theoretical simplicity, and it surveys the leading measures of simplicity and complexity currently on the market. Finally, Section 4 surveys the wide variety of attempts that have been made to justify the practice of choosing between rival theories on grounds of simplicity.

Table of Contents

- The Role of Simplicity in Science

- Ockham’s Razor

- Examples of Simplicity Preferences at Work in the History of Science

- Newton’s Argument for Universal Gravitation

- Other Examples

- Simplicity and Inductive Inference

- Simplicity in Statistics and Data Analysis

- Wider Philosophical Significance of Issues Surrounding Simplicity

- Defining and Measuring Simplicity

- Syntactic Measures

- Goodman’s Measure

- Simplicity as Testability

- Sober’s Measure

- Thagard’s Measure

- Information-Theoretic Measures

- Is Simplicity a Unified Concept?

- Justifying Preferences for Simpler Theories

- Simplicity as an Indicator of Truth

- Nature is Simple

- Meta-Inductive Proposals

- Bayesian Proposals

- Simplicity as a Fundamental A Priori Principle

- Alternative Justifications

- Falsifiability

- Simplicity as an Explanatory Virtue

- Predictive Accuracy

- Truth-Finding Efficiency

- Deflationary Approaches

- Conclusion

- References and Further Reading

1. The Role of Simplicity in Science

There are many ways in which simplicity might be regarded as a desirable feature of scientific theories. Simpler theories are frequently said to be more “beautiful” or more “elegant” than their rivals; they might also be easier to understand and to work with. However, according to many scientists and philosophers, simplicity is not something that is merely to be hoped for in theories; nor is it something that we should only strive for after we have already selected a theory that we believe to be on the right track (for example, by trying to find a simpler formulation of an accepted theory). Rather, the claim is that simplicity should actually be one of the key criteria that we use to evaluate which of a set of rival theories is, in fact, the best theory, given the available evidence: other things being equal, the simplest theory consistent with the data is the best one.

This view has a long and illustrious history. Though it is now most commonly associated with the 14th century philosopher, William of Ockham (also spelt “Occam”), whose name is attached to the famous methodological maxim known as “Ockham’s razor”, which is often interpreted as enjoining us to prefer the simplest theory consistent with the available evidence, it can be traced at least as far back as Aristotle. In his Posterior Analytics, Aristotle argued that nothing in nature was done in vain and nothing was superfluous, so our theories of nature should be as simple as possible. Several centuries later, at the beginning of the modern scientific revolution, Galileo espoused a similar view, holding that, “[n]ature does not multiply things unnecessarily; that she makes use of the easiest and simplest means for producing her effects” (Galilei, 1962, p396). Similarly, at beginning of the third book of the Principia, Isaac Newton included the following principle among his “rules for the study of natural philosophy”:

- No more causes of natural things should be admitted than are both true and sufficient to explain their phenomena.

As the philosophers say: Nature does nothing in vain, and more causes are in vain when fewer will suffice. For Nature is simple and does not indulge in the luxury of superfluous causes. (Newton, 1999, p794 [emphasis in original]).

In the 20th century, Albert Einstein asserted that “our experience hitherto justifies us in believing that nature is the realisation of the simplest conceivable mathematical ideas” (Einstein, 1954, p274). More recently, the eminent physicist Steven Weinberg has claimed that he and his fellow physicists “demand simplicity and rigidity in our principles before we are willing to take them seriously” (Weinberg, 1993, p148-9), while the Nobel prize winning economist John Harsanyi has stated that “[o]ther things being equal, a simpler theory will be preferable to a less simple theory” (quoted in McAlleer, 2001, p296).

It should be noted, however, that not all scientists agree that simplicity should be regarded as a legitimate criterion for theory choice. The eminent biologist Francis Crick once complained, “[w]hile Occam’s razor is a useful tool in physics, it can be a very dangerous implement in biology. It is thus very rash to use simplicity and elegance as a guide in biological research” (Crick, 1988, p138). Similarly, here are a group of earth scientists writing in Science:

- Many scientists accept and apply [Ockham’s Razor] in their work, even though it is an entirely metaphysical assumption. There is scant empirical evidence that the world is actually simple or that simple accounts are more likely than complex ones to be true. Our commitment to simplicity is largely an inheritance of 17th-century theology. (Oreskes et al, 1994, endnote 25)

Hence, while very many scientists assert that rival theories should be evaluated on grounds of simplicity, others are much more skeptical about this idea. Much of this skepticism stems from the suspicion that the cogency of a simplicity criterion depends on assuming that nature is simple (hardly surprising given the way that many scientists have defended such a criterion) and that we have no good reason to make such an assumption. Crick, for instance, seemed to think that such an assumption could make no sense in biology, given the patent complexity of the biological world. In contrast, some advocates of simplicity have argued that a preference for simple theories need not necessarily assume a simple world—for instance, even if nature is demonstrably complex in an ontological sense, we should still prefer comparatively simple explanations for nature’s complexity. Oreskes and others also emphasize that the simplicity principles of scientists such as Galileo and Newton were explicitly rooted in a particular kind of natural theology, which held that a simple and elegant universe was a necessary consequence of God’s benevolence. Today, there is much less enthusiasm for grounding scientific methods in theology (the putative connection between God’s benevolence and the simplicity of creation is theologically controversial in any case). Another common source of skepticism is the apparent vagueness of the notion of simplicity and the suspicion that scientists’ judgments about the relative simplicity of theories lack a principled and objective basis.

Even so, there is no doubting the popularity of the idea that simplicity should be used as a criterion for theory choice and evaluation. It seems to be explicitly ingrained into many scientific methods—for instance, standard statistical methods of data analysis (Section 1d). It has also spread far beyond philosophy and the natural sciences. A recent issue of the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, for instance, contained the advice that “[u]nfortunately, many people perceive criminal acts as more complex than they really are… the least complicated explanation of an event is usually the correct one” (Rothwell, 2006, p24).

a. Ockham’s Razor

Many scientists and philosophers endorse a methodological principle known as “Ockham’s Razor”. This principle has been formulated in a variety of different ways. In the early 21st century, it is typically just equated with the general maxim that simpler theories are “better” than more complex ones, other things being equal. Historically, however, it has been more common to formulate Ockham’s Razor as a more specific type of simplicity principle, often referred to as “the principle of parsimony”. Whether William of Ockham himself would have endorsed any of the wide variety of methodological maxims that have been attributed to him is a matter of some controversy (see Thorburn, 1918; entry on William of Ockham), since Ockham never explicitly referred to a methodological principle that he called his “razor”. However, a standard of formulation of the principle of parsimony—one that seems to be reasonably close to the sort of principle that Ockham himself probably would have endorsed—is as the maxim “entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity”. So stated, the principle is ontological, since it is concerned with parsimony with respect to the entities that theories posit the existence of in attempting to account for the empirical data. “Entity”, in this context, is typically understood broadly, referring not just to objects (for example, atoms and particles), but also to other kinds of natural phenomena that a theory may include in its ontology, such as causes, processes, properties, and so forth. Other, more general formulations of Ockham’s Razor are not exclusively ontological, and may also make reference to various structural features of how theories go about explaining nature, such as the unity of their explanations. The remainder of this section will focus on the more traditional ontological interpretation.

It is important to recognize that the principle, “entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity” can be read in at least two different ways. One way of reading it is as what we can call an anti-superfluity principle (Barnes, 2000). This principle calls for the elimination of ontological posits from theories that are explanatorily redundant. Suppose, for instance, that there are two theories, T1 and T2, which both seek to explain the same set of empirical data, D. Suppose also that T1 and T2 are identical in terms of the entities that are posited, except for the fact that T2 entails an additional posit, b, that is not part of T1. So let us say that T1 posits a, while T2 posits a + b. Intuitively, T2 is a more complex theory than T1 because it posits more things. Now let us assume that both theories provide an equally complete explanation of D, in the sense that there are no features of D that the two theories cannot account for. In this situation, the anti-superfluity principle would instruct us to prefer the simpler theory, T1, to the more complex theory, T2. The reason for this is because T2 contains an explanatorily redundant posit, b, which does no explanatory work in the theory with respect to D. We know this because T1, which posits a alone provides an equally adequate account of D as T2. Hence, we can infer that positing a alone is sufficient to acquire all the explanatory ability offered by T2, with respect to D; adding b does nothing to improve the ability of T2 to account for the data.

This sort of anti-superfluity principle underlies one important interpretation of “entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity”: as a principle that invites us to get rid of superfluous components of theories. Here, an ontological posit is superfluous with respect to a given theory, T, in so far as it does nothing to improve T’s ability to account for the phenomena to be explained. This is how John Stuart Mill understood Ockham’s razor (Mill, 1867, p526). Mill also pointed to a plausible justification for the anti-superfluity principle: explanatorily redundant posits—those that have no effect on the ability of the theory to explain the data—are also posits that do not obtain evidential support from the data. This is because it is plausible that theoretical entities are evidentially supported by empirical data only to the extent that they can help us to account for why the data take the form that they do. If a theoretical entity fails to contribute to this end, then the data fails to confirm the existence of this entity. If we have no other independent reason to postulate the existence of this entity, then we have no justification for including this entity in our theoretical ontology.

Another justification that has been offered for the anti-superfluity principle is a probabilistic one. Note that T2 is a logically stronger theory than T1: T2 says that a and b exist, while T1 says that only a exists. It is a consequence of the axioms of probability that a logically stronger theory is always less probable than a logically weaker theory, thus, so long as the probability of a existing and the probability of b existing are independent of each other, the probability of a existing is greater than zero, and the probability of b existing is less than 1, we can assert that Pr (a exists) > Pr (a exists & b exists), where Pr (a exists & b exists) = Pr (a exists) * Pr (b exists). According to this reasoning, we should therefore regard the claims of T1 as more a priori probable than the claims of T2, and this is a reason to prefer it. However, one objection to this probabilistic justification for the anti-superfluity principle is that it doesn’t fully explain why we dislike theories that posit explanatorily redundant entities: it can’t really because they are logically stronger theories; rather it is because they postulate entities that are unsupported by evidence.

When the principle of parsimony is read as an anti-superfluity principle, it seems relatively uncontroversial. However, it is important to recognize that the vast majority of instances where the principle of parsimony is applied (or has been seen as applying) in science cannot be given an interpretation merely in terms of the anti-superfluity principle. This is because the phrase “entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity” is normally read as what we can call an anti-quantity principle: theories that posit fewer things are (other things being equal) to be preferred to theories that posit more things, whether or not the relevant posits play any genuine explanatory role in the theories concerned (Barnes, 2000). This is a much stronger claim than the claim that we should razor off explanatorily redundant entities. The evidential justification for the anti-superfluity principle just described cannot be used to motivate the anti-quantity principle, since the reasoning behind this justification allows that we can posit as many things as we like, so long as all of the individual posits do some explanatory work within the theory. It merely tells us to get rid of theoretical ontology that, from the perspective of a given theory, is explanatorily redundant. It does not tell us that theories that posit fewer things when accounting for the data are better than theories that posit more things—that is, that sparser ontologies are better than richer ones.

Another important point about the anti-superfluity principle is that it does not give us a reason to assert the non-existence of the superfluous posit. Absence of evidence, is not (by itself) evidence for absence. Hence, this version of Ockham’s razor is sometimes also referred to as an “agnostic” razor rather than an “atheistic” razor, since it only motivates us to be agnostic about the razored-off ontology (Sober, 1981). It seems that in most cases where Ockham’s razor is appealed to in science it is intended to support atheistic conclusions—the entities concerned are not merely cut out of our theoretical ontology, their existence is also denied. Hence, if we are to explain why such a preference is justified we need will to look for a different justification. With respect to the probabilistic justification for the anti-superfluity principle described above, it is important to note that it is not an axiom of probability that Pr (a exists & b doesn’t exist) > Pr (a exists & b exists).

b. Examples of Simplicity Preferences at Work in the History of Science

It is widely believed that there have been numerous episodes in the history of science where particular scientific theories were defended by particular scientists and/or came to be preferred by the wider scientific community less for directly empirical reasons (for example, some telling experimental finding) than as a result of their relative simplicity compared to rival theories. Hence, the history of science is taken to demonstrate the importance of simplicity considerations in how scientists defend, evaluate, and choose between theories. One striking example is Isaac Newton’s argument for universal gravitation.

i. Newton’s Argument for Universal Gravitation

At beginning of the third book of the Principia, subtitled “The system of the world”, Isaac Newton described four “rules for the study of natural philosophy”:

- Rule 1 No more causes of natural things should be admitted than are both true and sufficient to explain their phenomena.

- As the philosophers say: Nature does nothing in vain, and more causes are in vain when fewer will suffice. For Nature is simple and does not indulge in the luxury of superfluous causes.

- Rule 2 Therefore, the causes assigned to natural effects of the same kind must be, so far as possible, the same.

- Rule 3 Those qualities of bodies that cannot be intended and remitted [i.e., qualities that cannot be increased and diminished] and that belong to all bodies on which experiments can be made should be taken as qualities of all bodies universally.

- For the qualities of bodies can be known only through experiments; and therefore qualities that square with experiments universally are to be regarded as universal qualities… Certainly ideal fancies ought not to be fabricated recklessly against the evidence of experiments, nor should we depart from the analogy of nature, since nature is always simple and ever consonant with itself…

- Rule 4 In experimental philosophy, propositions gathered from phenomena by induction should be considered either exactly or very nearly true notwithstanding any contrary hypotheses, until yet other phenomena make such propositions either more exact or liable to exceptions.

- This rule should be followed so that arguments based on induction may not be nullified by hypotheses. (Newton, 1999, p794-796).

Here we see Newton explicitly placing simplicity at the heart of his conception of the scientific method. Rule 1, a version of Ockham’s Razor, which, despite the use of the word “superfluous”, has typically been read as an anti-quantity principle rather than an anti-superfluity principle (see Section 1a), is taken to follow directly from the assumption that nature is simple, which is in turn taken to give rise to rules 2 and 3, both principles of inductive generalization (infer similar causes for similar effects, and assume to be universal in all bodies those properties found in all observed bodies). These rules play a crucial role in what follows, the centrepiece being the argument for universal gravitation.

After laying out these rules of method, Newton described several “phenomena”—what are in fact empirical generalizations, derived from astronomical observations, about the motions of the planets and their satellites, including the moon. From these phenomena and the rules of method, he then “deduced” several general theoretical propositions. Propositions 1, 2, and 3 state that the satellites of Jupiter, the primary planets, and the moon are attracted towards the centers of Jupiter, the sun, and the earth respectively by forces that keep them in their orbits (stopping them from following a linear path in the direction of their motion at any one time). These forces are also claimed to vary inversely with the square of the distance of the orbiting body (for example, Mars) from the center of the body about which it orbits (for example, the sun). These propositions are taken to follow from the phenomena, including the fact that the respective orbits can be shown to (approximately) obey Kepler’s law of areas and the harmonic law, and the laws of motion developed in book 1 of the Principia. Newton then asserted proposition 4: “The moon gravitates toward the earth and by the force of gravity is always drawn back from rectilinear motion and kept in its orbit” (p802). In other words, it is the force of gravity that keeps the moon in its orbit around the earth. Newton explicitly invoked rules 1 and 2 in the argument for this proposition (what has become known as the “moon-test”). First, astronomical observations told us how fast the moon accelerates towards the earth. Newton was then able to calculate what the acceleration of the moon would be at the earth’s surface, if it were to fall down to the earth. This turned out to be equal to the acceleration of bodies observed to fall in experiments conducted on earth. Since it is the force of gravity that causes bodies on earth to fall (Newton assumed his readers’ familiarity with “gravity” in this sense), and since both gravity and the force acting on the moon “are directed towards the center of the earth and are similar to each other and equal”, Newton asserted that “they will (by rules 1 and 2) have the same cause” (p805). Therefore, the forces that act on falling bodies on earth, and which keeps the moon in its orbit are one and the same: gravity. Given this, the force of gravity acting on terrestrial bodies could now be claimed to obey an inverse-square law. Through similar deployment of rules 1, 2, and 4, Newton was led to the claim that it is also gravity that keeps the planets in their orbits around the sun and the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn in their orbits, since these forces are also directed toward the centers of the sun, Jupiter, and Saturn, and display similar properties to the force of gravity on earth, such as the fact that they obey an inverse-square law. Therefore, the force of gravity was held to act on all planets universally. Through several more steps, Newton was eventually able to get to the principle of universal gravitation: that gravity is a mutually attractive force that acts on any two bodies whatsoever and is described by an inverse-square law, which says that the each body attracts the other with a force of equal magnitude that is proportional to the product of the masses of the two bodies and inversely proportional to the squared distance between them. From there, Newton was able to determine the masses and densities of the sun, Jupiter, Saturn, and the earth, and offer a new explanation for the tides of the seas, thus showing the remarkable explanatory power of this new physics.

Newton’s argument has been the subject of much debate amongst historians and philosophers of science (for further discussion of the various controversies surrounding its structure and the accuracy of its premises, see Glymour, 1980; Cohen, 1999; Harper, 2002). However, one thing that seems to be clear is that his conclusions are by no means forced on us through simple deductions from the phenomena, even when combined with the mathematical theorems and general theory of motion outlined in book 1 of the Principia. No experiment or mathematical derivation from the phenomena demonstrated that it must be gravity that is the common cause of the falling of bodies on earth, the orbits of the moon, the planets and their satellites, much less that gravity is a mutually attractive force acting on all bodies whatsoever. Rather, Newton’s argument appears to boil down to the claim that if gravity did have the properties accorded to it by the principle of universal gravitation, it could provide a common causal explanation for all the phenomena, and his rules of method tell us to infer common causes wherever we can. Hence, the rules, which are in turn grounded in a preference for simplicity, play a crucial role in taking us from the phenomena to universal gravitation (for further discussion of the apparent link between simplicity and common cause reasoning, see Sober, 1988). Newton’s argument for universal gravitation can thus be seen as argument to the putatively simplest explanation for the empirical observations.

ii. Other Examples

Numerous other putative examples of simplicity considerations at work in the history of science have been cited in the literature:

- One of the most commonly cited concerns Copernicus’ arguments for the heliocentric theory of planetary motion. Copernicus placed particular emphasis on the comparative “simplicity” and “harmony” of the account that his theory gave of the motions of the planets compared with the rival geocentric theory derived from the work of Ptolemy. This argument appears to have carried significant weight for Copernicus’ successors, including Rheticus, Galileo, and Kepler, who all emphasized simplicity as a major motivation for heliocentrism. Philosophers have suggested various reconstructions of the Copernican argument (see for example, Glymour, 1980; Rosencrantz, 1983; Forster and Sober, 1994; Myrvold, 2003; Martens, 2009). However, historians of science have questioned the extent to which simplicity could have played a genuine rather than purely rhetorical role in this episode. For example, it has been argued that there is no clear sense in which the Copernican system was in fact simpler than Ptolemy’s, and that geocentric systems such as the Tychronic system could be constructed that were at least as simple as the Copernican one (for discussion, see Kuhn, 1957; Palter, 1970; Cohen, 1985; Gingerich, 1993; Martens, 2009).

- It has been widely claimed that simplicity played a key role in the development of Einstein’s theories of theories of special and general relativity, and in the early acceptance of Einstein’s theories by the scientific community (see for example, Hesse, 1974; Holton, 1974; Schaffner, 1974; Sober, 1981; Pais, 1982; Norton, 2000).

- Thagard (1988) argues that simplicity considerations played an important role in Lavoisier’s case against the existence of phlogiston and in favour of the oxygen theory of combustion.

- Carlson (1966) describes several episodes in the history of genetics in which simplicity considerations seemed to have held sway.

- Nolan (1997) argues that a preference for ontological parsimony played an important role in the discovery of the neutrino and in the proposal of Avogadro’s hypothesis.

- Baker (2007) argues that ontological parsimony was a key issue in discussions over rival dispersalist and extensionist bio-geographical theories in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Though it is commonplace for scientists and philosophers to claim that simplicity considerations have played a significant role in the history of science, it is important to note that some skeptics have argued that the actual historical importance of simplicity considerations has been over-sold (for example, Bunge, 1961; Lakatos and Zahar, 1978). Such skeptics dispute the claim that we can only explain the basis for these and other episodes of theory change by according a role to simplicity, claiming other considerations actually carried more weight. In addition, it has been argued that, in many cases, what appear on the surface to have been appeals to the relative simplicity of theories were in fact covert appeals to some other theoretical virtue (for example, Boyd, 1990; Sober, 1994; Norton, 2003; Fitzpatrick, 2009). Hence, for any putative example of simplicity at work in the history of science, it is important to consider whether the relevant arguments are not best reconstructed in other terms (such a “deflationary” view of simplicity will be discussed further in Section 4c).

c. Simplicity and Inductive Inference

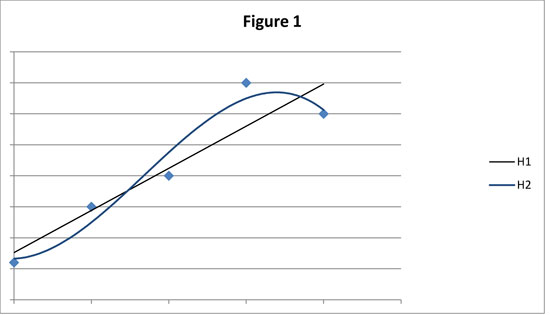

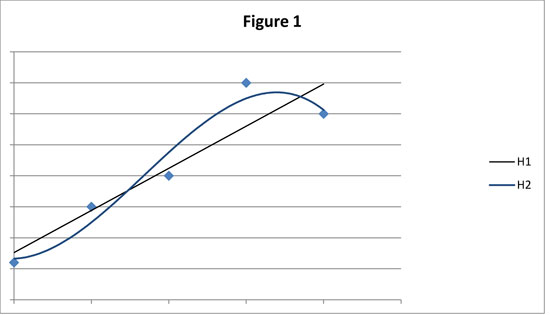

Many philosophers have come to see simplicity considerations figuring not only in how scientists go about evaluating and choosing between developed scientific theories, but also in the mechanics of making much more basic inductive inferences from empirical data. The standard illustration of this in the modern literature is the practice of curve-fitting. Suppose that we have a series of observations of the values of a variable, y, given values of another variable, x. This gives us a series of data points, as represented in Figure 1.

Given this data, what underlying relationship should we posit between x and y so that we can predict future pairs of x–y values? Standard practice is not to select a bumpy curve that neatly passes through all the data points, but rather to select a smooth curve—preferably a straight line, such as H1—that passes close to the data. But why do we do this? Part of an answer comes from the fact that if the data is to some degree contaminated with measurement error (for example, through mistakes in data collection) or “noise” produced by the effects of uncontrolled factors, then any curve that fits the data perfectly will most likely be false. However, this does not explain our preference for a curve like H1 over an infinite number of other curves—H2, for instance—that also pass close to the data. It is here that simplicity has been seen as playing a vital, though often implicit role in how we go about inferring hypotheses from empirical data: H1 posits a “simpler” relationship between x and y than H2—hence, it is for reasons of simplicity that we tend to infer hypotheses like H1.

The practice of curve-fitting has been taken to show that—whether we aware of it or not—human beings have a fundamental cognitive bias towards simple hypotheses. Whether we are deciding between rival scientific theories, or performing more basic generalizations from our experience, we ubiquitously tend to infer the simplest hypothesis consistent with our observations. Moreover, this bias is held to be necessary in order for us to be able select a unique hypotheses from the potentially limitless number of hypotheses consistent with any finite amount of experience.

The view that simplicity may often play an implicit role in empirical reasoning can arguably be traced back to David Hume’s description of enumerative induction in the context of his formulation of the famous problem of induction. Hume suggested that a tacit assumption of the uniformity of nature is ingrained into our psychology. Thus, we are naturally drawn to the conclusion that all ravens have black feathers from the fact that all previously observed ravens have black feathers because we tacitly assume that the world is broadly uniform in its properties. This has been seen as a kind of simplicity assumption: it is simpler to assume more of the same.

A fundamental link between simplicity and inductive reasoning has been retained in many more recent descriptive accounts of inductive inference. For instance, Hans Reichenbach (1949) described induction as an application of what he called the “Straight Rule”, modelling all inductive inference on curve-fitting. In addition, proponents of the model of “Inference to Best Explanation”, who hold that many inductive inferences are best understood as inferences to the hypothesis that would, if true, provide the best explanation for our observations, normally claim that simplicity is one of the criteria that we use to determine which hypothesis constitutes the “best” explanation.

In recent years, the putative role of simplicity in our inferential psychology has been attracting increasing attention from cognitive scientists. For instance, Lombrozo (2007) describes experiments that she claims show that participants use the relative simplicity of rival explanations (for instance, whether a particular medical diagnosis for a set of symptoms involves assuming the presence of one or multiple independent conditions) as a guide to assessing their probability, such that a disproportionate amount of contrary probabilistic evidence is required for participants to choose a more complex explanation over a simpler one. Simplicity considerations have also been seen as central to learning processes in many different cognitive domains, including language acquisition and category learning (for example, Chater, 1999; Lu and others, 2006).

d. Simplicity in Statistics and Data Analysis

Philosophers have long used the example of curve-fitting to illustrate the (often implicit) role played by considerations of simplicity in inductive reasoning from empirical data. However, partly due to the advent of low-cost computing power and that the fact scientists in many disciplines find themselves having to deal with ever larger and more intricate bodies of data, recent decades have seen a remarkable revolution in the methods available to scientists for analyzing and interpreting empirical data (Gauch, 2006). Importantly, there are now numerous formalized procedures for data analysis that can be implemented in computer software—and which are widely used in disciplines from engineering to crop science to sociology—that contain an explicit role for some notion of simplicity. The literature on such methods abounds with talk of “Ockham’s Razor”, “Occam factors”, “Ockham’s hill” (MacKay, 1992; Gauch, 2006), “Occam’s window” (Raftery and others, 1997), and so forth. This literature not only provides important illustrations of the role that simplicity plays in scientific practice, but may also offer insights for philosophers seeking to understand the basis for this role.

As an illustration, consider standard procedures for model selection, such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Minimum Message Length (MML) and Minimum Description Length (MDL) procedures, and numerous others (for discussion see, Forster and Sober, 1994; Forster, 2001; Gauch, 2003; Dowe and others, 2007). Model selection is a matter of selecting the kind of relationship that is to be posited between a set of variables, given a sample of data, in an effort to generate hypotheses about the true underlying relationship holding in the population of inference and/or to make predictions about future data. This question arises in the simple curve-fitting example discussed above—for instance, whether the true underlying relationship between x and y is linear, parabolic, quadratic, and so on. It also arises in lots of other contexts, such as the problem of inferring the causal relationship that exists between an empirical effect and a set of variables. “Models” in this sense are families of functions, such as the family of linear functions, LIN: y = a + bx, or the family of parabolic functions, PAR: y = a + bx + cx2. The simplicity of a model is normally explicated in terms of the number of adjustable parameters it contains (MML and MDL measure the simplicity of models in terms of the extent to which they provide compact descriptions of the data, but produce similar results to the counting of adjustable parameters). On this measure, the model LIN is simpler than PAR, since LIN contains two adjustable parameters, whereas PAR has three. A consequence of this is that a more complex model will always be able to fit a given sample of data better than a simpler model (“fitting” a model to the data involves using the data to determine what the values of the parameters in the model should be, given that data—that is, identifying the best-fitting member of the family). For instance, returning to the curve-fitting scenario represented in Figure 1, the best-fitting curve in PAR is guaranteed to fit this data set at least as well as the best-fitting member of the simpler model, LIN, and this is true no matter what the data are, since linear functions are special cases of parabolas, where c = 0, so any curve that is a member of LIN is also a member of PAR.

Model selection procedures produce a ranking of all the models under consideration in light of the data, thus allowing scientists to choose between them. Though they do it in different ways, AIC, BIC, MML, and MDL all implement procedures for model selection that impose a penalty on the complexity of a model, so that a more complex model will have to fit the data sample at hand significantly better than a simpler one for it to be rated higher than the simpler model. Often, this penalty is greater the smaller is the sample of data. Interestingly—and contrary to the assumptions of some philosophers—this seems to suggest that simplicity considerations do not only come into play as a tiebreaker between theories that fit the data equally well: according to the model selection literature, simplicity sometimes trumps better fit to the data. Hence, simplicity need not only come into play when all other things are equal.

Both statisticians and philosophers of statistics have vigorously debated the underlying justification for these sorts of model selection procedures (see, for example, the papers in Zellner and others, 2001). However, one motivation for taking into account the simplicity of models derives from a piece of practical wisdom: when there is error or “noise” in the data sample, a relatively simple model that fits the sample less well will often be more accurate when it comes to predicting extra-sample (for example, future) data than a more complex model that fits the sample more closely. The logic here is that since more complex models are more flexible in their ability to fit the data (since they have more adjustable parameters), they also have a greater propensity to be misled by errors and noise, in which case they may recover less of the true underlying “signal” in the sample. Thus, constraining model complexity may facilitate greater predictive accuracy. This idea is captured in what Gauch (2003, 2006) (following MacKay, 1992) calls “Ockham’s hill”. To the left of the peak of the hill, increasing the complexity of a model improves its accuracy with respect to extra-sample data because this recovers more of the signal in the sample. However, after the peak, increasing complexity actually diminishes predictive accuracy because this leads to over-fitting to spurious noise in the sample. There is therefore an optimal trade-off (at the peak of Ockham’s hill) between simplicity and fit to the sample data when it comes to facilitating accurate prediction of extra-sample data. Indeed, this trade-off is essentially the core idea behind AIC, the development of which initiated the now enormous literature on model selection, and the philosophers Malcolm Forster and Elliott Sober have sought to use such reasoning to make sense of the role of simplicity in many areas of science (see Section 4biii).

One important implication of this apparent link between model simplicity and predictive accuracy is that interpreting sample data using relatively simple models may improve the efficiency of experiments by allowing scientists to do more with less data—for example, scientists may be able to run a costly experiment fewer times before they can be in a position to make relatively accurate predictions about the future. Gauch (2003, 2006) describes several real world cases from crop science and elsewhere where this gain in accuracy and efficiency from the use of relatively simple models has been documented.

2. Wider Philosophical Significance of Issues Surrounding Simplicity

The putative role of simplicity, both in the evaluation of rival scientific theories and in the mechanics of how we go about inferring hypotheses from empirical data, clearly raises a number of difficult philosophical issues. These include, but are by no means limited to: (1) the question of what precisely it means to say the one theory or hypothesis is simpler than another and how the relative simplicity of theories is to be measured; (2) the question of what rational justification (if any) can be provided for choosing between rival theories on grounds of simplicity; and (3) the closely related question of what weight simplicity considerations ought to carry in theory choice relative to other theoretical virtues, particularly if these sometimes have to be traded-off against each other. (For general surveys of the philosophical literature on these issues, see Hesse, 1967; Sober, 2001a, 2001b). Before we delve more deeply into how philosophers have sought to answer these questions, it is worth noting the close connections between philosophical issues surrounding simplicity and many of the most important controversies in the philosophy of science and epistemology.

First, the problem of simplicity has close connections with long-standing issues surrounding the nature and justification of inductive inference. Some philosophers have actually offered up the idea that simpler theories are preferable to less simple ones as a purported solution to the problem of induction: it is the relative simplicity of the hypotheses that we tend to infer from empirical observations that supposedly provides the justification for these inferences—thus, it is simplicity that provides the warrant for our inductive practices. This approach is not as popular as it once was, since it is taken to merely substitute the problem of induction for the equally substantive problem of justifying preferences for simpler theories. A more common view in the recent literature is that the problem of induction and the problem of justifying preferences for simpler theories are closely connected, or may even amount to the same problem. Hence, a solution to the latter problem will provide substantial help towards solving the former.

More generally, the ability to make sense of the putative role of simplicity in scientific reasoning has been seen by many to be a central desideratum for any adequate philosophical theory of the scientific method. For example, Thomas Kuhn’s (1962) influential discussion of the importance of scientists’ aesthetic preferences—including but not limited to judgments of simplicity—in scientific revolutions was a central part of his case for adopting a richer conception of the scientific method and of theory change in science than he found in the dominant logical empiricist views of the time. More recently, critics of the Bayesian approach to scientific reasoning and theory confirmation, which holds that sound inductive reasoning is reasoning according to the formal principles of probability, have claimed that simplicity is an important feature of scientific reasoning that escapes a Bayesian analysis. For instance, Forster and Sober (1994) argue that Bayesian approaches to curve-fitting and model selection (such as the Bayesian Information Criterion) cannot themselves be given Bayesian rationale, nor can any other approach that builds in a bias towards simpler models. The ability of the Bayesian approach to make sense of simplicity in model selection and other aspects of scientific practice has thus been seen as central to evaluating its promise (see for example, Glymour, 1980; Forster and Sober, 1994; Forster, 1995; Kelly and Glymour, 2004; Howson and Urbach, 2006; Dowe and others, 2007).

Discussions over the legitimacy of simplicity as a criterion for theory choice have also been closely bound up with debates over scientific realism. Scientific realists assert that scientific theories aim to offer a literally true description of the world and that we have good reason to believe that the claims of our current best scientific theories are at least approximately true, including those claims that purport to be about “unobservable” natural phenomena that are beyond our direct perceptual access. Some anti-realists object that it is possible to formulate incompatible alternatives to our current best theories that are just as consistent with any current data that we have, perhaps even any future data that we could ever collect. They claim that we can therefore never be justified in asserting that the claims of our current best theories, especially those concerning unobservables, are true, or approximately true. A standard realist response is to emphasize the role of the so-called “theoretical virtues” in theory choice, among which simplicity is normally listed. The claim is thus that we rule out these alternative theories because they are unnecessarily complex. Importantly, for this defense to work, realists have to defend the idea that not only are we justified in choosing between rival theories on grounds of simplicity, but also that simplicity can be used as a guide to the truth. Naturally, anti-realists, particularly those of an empiricist persuasion (for example, van Fraassen, 1989), have expressed deep skepticism about the alleged truth-conduciveness of a simplicity criterion.

3. Defining and Measuring Simplicity

The first major philosophical problem that seems to arise from the notion that simplicity plays a role in theory choice and evaluation concerns specifying in more detail what it means to say that one theory is simpler than another and how the relative simplicity of theories is to be precisely and objectively measured. Numerous attempts have been made to formulate definitions and measures of theoretical simplicity, all of which face very significant challenges. Philosophers have not been the only ones to contribute to this endeavour. For instance, over the last few decades, a number of formal measures of simplicity and complexity have been developed in mathematical information theory. This section provides an overview of some of the main simplicity measures that have been proposed and the problems that they face. The proposals described here have also normally been tied to particular proposals about what justifies preferences for simpler theories. However, discussion of these justifications will be left until Section 4.

To begin with, it is worth considering why providing a precise definition and measure of theoretical simplicity ought to be regarded as a substantial philosophical problem. After all, it often seems that when one is confronted with a set of rival theories designed to explain a particular empirical phenomenon, it is just obvious which is the simplest. One does not always need a precise definition or measure of a particular property to be able to tell whether or not something exhibits it to a greater degree than something else. Hence, it could be suggested that if there is a philosophical problem here, it is only of very minor interest and certainly of little relevance to scientific practice. There are, however, some reasons to regard this as a substantial philosophical problem, which also has some practical relevance.

First, it is not always easy to tell whether one theory really ought to be regarded as simpler than another, and it is not uncommon for practicing scientists to disagree about the relative simplicity of rival theories. A well-known historical example is the disagreement between Galileo and Kepler concerning the relative simplicity of Copernicus’ theory of planetary motion, according to which the planets move only in perfect circular orbits with epicycles, and Kepler’s theory, according to which the planets move in elliptical orbits (see Holton, 1974; McAllister, 1996). Galileo held to the idea that perfect circular motion is simpler than elliptical motion. In contrast, Kepler emphasized that an elliptical model of planetary motion required many fewer orbits than a circular model and enabled a reduction of all the planetary motions to three fundamental laws of planetary motion. The problem here is that scientists seem to evaluate the simplicity of theories along a number of different dimensions that may conflict with each other. Hence, we have to deal with the fact that a theory may be regarded as simpler than a rival in one respect and more complex in another. To illustrate this further, consider the following list of commonly cited ways in which theories may be held to be simpler than others:

- Quantitative ontological parsimony (or economy): postulating a smaller number of independent entities, processes, causes, or events.

- Qualitative ontological parsimony (or economy): postulating a smaller number of independent kinds or classes of entities, processes, causes, or events.

- Common cause explanation: accounting for phenomena in terms of common rather than separate causal processes.

- Symmetry: postulating that equalities hold between interacting systems and that the laws describing the phenomena look the same from different perspectives.

- Uniformity (or homogeneity): postulating a smaller number of changes in a given phenomenon and holding that the relations between phenomena are invariant.

- Unification: explaining a wider and more diverse range of phenomena that might otherwise be thought to require separate explanations in a single theory (theoretical reduction is generally held to be a species of unification).

- Lower level processes: when the kinds of processes that can be posited to explain a phenomena come in a hierarchy, positing processes that come lower rather than higher in this hierarchy.

- Familiarity (or conservativeness): explaining new phenomena with minimal new theoretical machinery, reusing existing patterns of explanation.

- Paucity of auxiliary assumptions: invoking fewer extraneous assumptions about the world.

- Paucity of adjustable parameters: containing fewer independent parameters that the theory leaves to be determined by the data.

As can be seen from this list, there is considerable diversity here. We can see that theoretical simplicity is frequently thought of in ontological terms (for example, quantitative and qualitative parsimony), but also sometimes as a structural feature of theories (for example, unification, paucity of adjustable parameters), and while some of these intuitive types of simplicity may often cluster together in theories—for instance, qualitative parsimony would seem to often go together with invoking common cause explanations, which would in turn often seem to go together with explanatory unification—there is also considerable scope for them pointing in different directions in particular cases. For example, a theory that is qualitatively parsimonious as a result of positing fewer different kinds of entities might be quantitatively unparsimonious as result of positing more of a particular kind of entity; while the demand to explain in terms of lower-level processes rather than higher-level processes may conflict with the demand to explain in terms of common causes behind similar phenomena, and so on. There are also different possible ways of evaluating the simplicity of a theory with regard to any one of these intuitive types of simplicity. A theory may, for instance, come out as more quantitatively parsimonious than another if one focuses on the number of independent entities that it posits, but less parsimonious if one focuses on the number of independent causes it invokes. Consequently, it seems that if a simplicity criterion is actually to be applicable in practice, we need some way of resolving the disagreements that may arise between scientists about the relative simplicity of rival theories, and this requires a more precise measure of simplicity.

Second, as has already been mentioned, a considerable amount of the skepticism expressed both by philosophers and by scientists about the practice of choosing one theory over another on grounds of relative simplicity has stemmed from the suspicion that our simplicity judgments lack a principled basis (for example, Ackerman, 1961; Bunge, 1961; Priest, 1976). Disagreements between scientists, along with the multiplicity and scope for conflict between intuitive types of simplicity have been important contributors to this suspicion, leading to the view that for any two theories, T1 and T2, there is some way of evaluating their simplicity such that T1 comes out as simpler than T2, and vice versa. It seems, then, that an adequate defense of the legitimacy a simplicity criterion needs to show that there are in fact principled ways of determining when one theory is indeed simpler than another. Moreover, in so far as there is also a justificatory issue to be dealt with, we also need to be clear about exactly what it is that we need to justify a preference for.

a. Syntactic Measures

One proposal is that the simplicity of theories can be precisely and objectively measured in terms of how briefly they can be expressed. For example, a natural way of measuring the simplicity of an equation is just to count the number of terms, or parameters that it contains. Similarly, we could measure the simplicity of a theory in terms of the size of the vocabulary—for example, the number of extra-logical terms—required to write down its claims. Such measures of simplicity are often referred to as syntactic measures, since they involve counting the linguistic elements required to state, or to describe the theory.

A major problem facing any such syntactic measure of simplicity is the problem of language variance. A measure of simplicity is language variant if it delivers different results depending on the language that is used to represent the theories being compared. Suppose, for example, that we measure the simplicity of an equation by counting the number of non-logical terms that it contains. This will produce the result that r = a will come out as simpler than x2 + y2 = a2. However, this second equation is simply a transformation of the first into Cartesian co-ordinates, where r2 = x2 + y2, and is hence logically equivalent. The intuitive proposal for measuring simplicity in curve-fitting contexts, according to which hypotheses are said to be simpler if they contain fewer parameters, is also language variant in this sense. How many parameters a hypothesis contains depends on the co-ordinate scales that one uses. For any two non-identical functions, F and G, there is some way of transforming the co-ordinate scales such that we can turn F into a linear curve and G into a non-linear curve, and vice versa.

Nelson Goodman’s (1983) famous “new riddle of induction” allows us to formulate another example of the problem of language variance. Suppose all previously observed emeralds have been green. Now consider the following hypotheses about the color properties of the entire population of emeralds:

- H1: all emeralds are green

- H2: all emeralds first observed prior to time t are green and all emeralds first observed after time t are blue (where t is some future time)

Intuitively, H1 seems to be a simpler hypothesis than H2. To begin with, it can be stated with a smaller vocabulary. H1 also seems to postulate uniformity in the properties of emeralds, while H2 posits non-uniformity. For instance, H2 seems to assume that there is some link between the time at which an emerald is first observed and its properties. Thus it can be viewed as including an additional time parameter. But now consider Goodman’s invented predicates, “grue” and “bleen”. These have been defined in variety of different ways, but let us define them here as follows: an object is grue if it is first observed before time t and the object is green, or first observed after t and the object is blue; an object is bleen if it is first observed before time t and the object is blue, or first observed after the time t and the object is green. With these predicates, we can define a further property, “grolor”. Grue and bleen are grolors just as green and blue are colors. Now, because of the way that grolors are defined, color predicates like “green” and “blue” can also be defined in terms of grolor predicates: an object is green if first observed before time t and the object is grue, or first observed after time t and the object is bleen; an object is blue if first observed before time t and the object is bleen, or first observed after t and the object is grue. This means that statements that are expressed in terms of green and blue can also be expressed in terms of grue and bleen. So, we can rewrite H1 and H2 as follows:

- H1: all emeralds first observed prior to time t are grue and all emeralds first observed after time t are bleen (where t is some future time)

- H2: all emeralds are grue

Re-call that earlier we judged H1 to be simpler than H2. However, if we are retain that simplicity judgment, we cannot say that H1 is simpler than H2 because it can be stated with a smaller vocabulary; nor can we say that it H1 posits greater uniformity, and is hence simpler, because it does not contain a time parameter. This is because simplicity judgments based on such syntactic features can be reversed merely by switching the language used to represent the hypotheses from a color language to a grolor language.

Examples such as these have been taken to show two things. First, no syntactic measure of simplicity can suffice to produce a principled simplicity ordering, since all such measures will produce different results depending of the language of representation that is used. It is not enough just to stipulate that we should evaluate simplicity in one language rather than another, since that would not explain why simplicity should be measured in that way. In particular, we want to know that our chosen language is accurately tracking the objective language-independent simplicity of the theories being compared. Hence, if a syntactic measure of simplicity is to be used, say for practical purposes, it must be underwritten by a more fundamental theory of simplicity. Second, a plausible measure of simplicity cannot be entirely neutral with respect to all of the different claims about the world that the theory makes or can be interpreted as making. Because of the respective definitions of colors and grolors, any hypothesis that posits uniformity in color properties must posit non-uniformity in grolor properties. As Goodman emphasized, one can find uniformity anywhere if no restriction is placed on what kinds of properties should be taken into account. Similarly, it will not do to say that theories are simpler because they posit the existence of fewer entities, causes and processes, since, using Goodman-like manipulations, it is trivial to show that a theory can be regarded as positing any number of different entities, causes and processes. Hence, some principled restriction needs to be placed on which aspects of the content of a theory are to be taken into account and which are to be disregarded when measuring their relative simplicity.

b. Goodman’s Measure

According to Nelson Goodman, an important component of the problem of measuring the simplicity of scientific theories is the problem of measuring the degree of systematization that a theory imposes on the world, since, for Goodman, to seek simplicity is to seek a system. In a series of papers in the 1940s and 50s, Goodman (1943, 1955, 1958, 1959) attempted to explicate a precise measure of theoretical systematization in terms of the logical properties of the set of concepts, or extra-logical terms, that make up the statements of the theory.

According to Goodman, scientific theories can be regarded as sets of statements. These statements contain various extra-logical terms, including property terms, relation terms, and so on. These terms can all be assigned predicate symbols. Hence, all the statements of a theory can be expressed in a first order language, using standard symbolic notion. For instance, “… is acid” may become “A(x)”, “… is smaller than ____” may become “S(x, y)”, and so on. Goodman then claims that we can measure the simplicity of the system of predicates employed by the theory in terms of their logical properties, such as their arity, reflexivity, transitivity, symmetry, and so on. The details arehighly technical but, very roughly, Goodman’s proposal is that a system of predicates that can be used to express more is more complex than a system of predicates that can be used to express less. For instance, one of the axioms of Goodman’s proposal is that if every set of predicates of a relevant kind, K, is always replaceable by a set of predicates of another kind, L, then K is not more complex than L.

Part of Goodman’s project was to avoid the problem of language variance. Goodman’s measure is a linguistic measure, since it concerns measuring the simplicity of a theory’s predicate basis in a first order language. However, it is not a purely syntactic measure, since it does not involve merely counting linguistic elements, such as the number of extra-logical predicates. Rather, it can be regarded as an attempt to measure the richness of a conceptual scheme: conceptual schemes that can be used to say more are more complex than conceptual schemes that can be used to say less. Hence, a theory can be regarded as simpler if it requires a less expressive system of concepts.

Goodman developed his axiomatic measure of simplicity in considerable detail. However, Goodman himself only ever regarded it as a measure of one particular type of simplicity, since it only concerns the logical properties of the predicates employed by the theory. It does not, for example, take account of the number of entities that a theory postulates. Moreover, Goodman never showed how the measure could be applied to real scientific theories. It has been objected that even if Goodman’s measure could be applied, it would not discriminate between many theories that intuitively differ in simplicity—indeed, in the kind of simplicity as systematization that Goodman wants to measure. For instance, it is plausible that the system of concepts used to express the Copernican theory of planetary motion is just as expressively rich as the system of concepts used to express the Ptolemaic theory, yet the former is widely regarded as considerably simpler than the latter, partly in virtue of it providing an intuitively more systematic account of the data (for discussion of the details of Goodman’s proposal and the objections it faces, see Kemeny, 1955; Suppes, 1956; Kyburg, 1961; Hesse, 1967).

c. Simplicity as Testability

It has often been argued that simpler theories say more about the world and hence are easier to test than more complex ones. C. S. Peirce (1931), for example, claimed that the simplest theories are those whose empirical consequences are most readily deduced and compared with observation, so that they can be eliminated more easily if they are wrong. Complex theories, on the other hand, tend to be less precise and allow for more wriggle room in accommodating the data. This apparent connection between simplicity and testability has led some philosophers to attempt to formulate measures of simplicity in terms of the relative testability of theories.

Karl Popper (1959) famously proposed one such testability measure of simplicity. Popper associated simplicity with empirical content: simpler theories say more about the world than more complex theories and, in so doing, place more restriction on the ways that the world can be. According to Popper, the empirical content of theories, and hence their simplicity, can be measured in terms of their falsifiability. The falsifiability of a theory concerns the ease with which the theory can be proven false, if the theory is indeed false. Popper argued that this could be measured in terms of the amount of data that one would need to falsify the theory. For example, on Popper’s measure, the hypothesis that x and y are linearly related, according to an equation of the form, y = a + bx, comes out as having greater empirical content and hence greater simplicity than the hypotheses that they are related according a parabola of the form, y = a + bx + cx2. This is because one only needs three data points to falsify the linear hypothesis, but one needs at least four data points to falsify the parabolic hypothesis. Thus Popper argued that empirical content, falsifiability, and hence simplicity, could be seen as equivalent to the paucity of adjustable parameters. John Kemeny (1955) proposed a similar testability measure, according to which theories are more complex if they can come out as true in more ways in an n-member universe, where n is the number of individuals that the universe contains.

Popper’s equation of simplicity with falsifiability suffers from some serious objections. First, it cannot be applied to comparisons between theories that make equally precise claims, such as a comparison between a specific parabolic hypothesis and a specific linear hypothesis, both of which specify precise values for their parameters and can be falsified by only one data point. It also cannot be applied when we compare theories that make probabilistic claims about the world, since probabilistic statements are not strictly falsifiable. This is particularly troublesome when it comes to accounting for the role of simplicity in the practice of curve-fitting, since one normally has to deal with the possibility of error in the data. As a result, an error distribution is normally added to the hypotheses under consideration, so that they are understood as conferring certain probabilities on the data, rather than as having deductive observational consequences. In addition, most philosophers of science now tend to think that falsifiability is not really an intrinsic property of theories themselves, but rather a feature of how scientists are disposed to behave towards their theories. Even deterministic theories normally do not entail particular observational consequences unless they are conjoined with particular auxiliary assumptions, usually leaving the scientist the option of saving the theory from refutation by tinkering with their auxiliary assumptions—a point famously emphasized by Pierre Duhem (1954). This makes it extremely difficult to maintain that simpler theories are intrinsically more falsifiable than less simple ones. Goodman (1961, p150-151) also argued that equating simplicity with falsifiability leads to counter-intuitive consequences. The hypothesis, “All maple trees are deciduous”, is intuitively simpler than the hypothesis, “All maple trees whatsoever, and all sassafras trees in Eagleville, are deciduous”, yet, according to Goodman, the latter hypothesis is clearly the easiest to falsify of the two. Kemeny’s measure inherits many of the same objections.

Both Popper and Kemeny essentially tried to link the simplicity of a theory with the degree to which it can accommodate potential future data: simpler theories are less accommodating than more complex ones. One interesting recent attempt to make sense of this notion of accommodation is due to Harman and Kulkarni (2007). Harman and Kulkarni analyze accommodation in terms of a concept drawn from statistical learning theory known as the Vapnik-Chervonenkis (VC) dimension. The VC dimension of a hypothesis can be roughly understood as a measure of the “richness” of the class of hypotheses from which it is drawn, where a class is richer if it is harder to find data that is inconsistent with some member of the class. Thus, a hypothesis drawn from a class that can fit any possible set of data will have infinite VC dimension. Though VC dimension shares some important similarities with Popper’s measure, there are important differences. Unlike Popper’s measure, it implies that accommodation is not always equivalent to the number of adjustable parameters. If we count adjustable parameters, sine curves of the form y = a sin bx, come out as relatively unaccommodating, however, such curves have an infinite VC dimension. While Harman and Kulkarni do not propose that VC dimension be taken as a general measure of simplicity (in fact, they regard it as an alternative to simplicity in some scientific contexts), ideas along these lines might perhaps hold some future promise for testability/accommodation measures of simplicity. Similar notions of accommodation in terms of “dimension” have been used to explicate the notion of the simplicity of a statistical model in the face of the fact the number of adjustable parameters a model contains is language variant (for discussion, see Forster, 1999; Sober, 2007).

d. Sober’s Measure

In his early work on simplicity, Elliott Sober (1975) proposed that the simplicity of theories be measured in terms of their question-relative informativeness. According to Sober, a theory is more informative if it requires less supplementary information from us in order for us to be able to use it to determine the answer to the particular questions that we are interested in. For instance, the hypothesis, y = 4x, is more informative and hence simpler than y = 2z + 2x with respect to the question, “what is the value of y?” This is because in order to find out the value of y one only needs to determine a value for x on the first hypothesis, whereas on the second hypothesis one also needs to determine a value for z. Similarly, Sober’s proposal can be used to capture the intuition that theories that say that a given class of things are uniform in their properties are simpler than theories that say that the class is non-uniform, because they are more informative relative to particular questions about the properties of the class. For instance, the hypothesis that “all ravens are black” is more informative and hence simpler than “70% of ravens are black” with respect to the question, “what will be the colour of the next observed raven?” This is because on the former hypothesis one needs no additional information in order to answer this question, whereas one will have to supplement the latter hypothesis with considerable extra information in order to generate a determinate answer.

By relativizing the notion of the content-fullness of theories to the question that one is interested in, Sober’s measure avoids the problem that Popper and Kemeny’s proposals faced of the most arbitrarily specific theories, or theories made up of strings of irrelevant conjunctions of claims, turning out to be the simplest. Moreover, according to Sober’s proposal, the content of the theory must be relevant to answering the question for it to count towards the theory’s simplicity. This gives rise to the most distinctive element of Sober’s proposal: different simplicity orderings of theories will be produced depending on the question one asks. For instance, if we want to know what the relationship is between values of z and given values of y and x, then y = 2z + 2x will be more informative, and hence simpler, than y = 4x. Thus, a theory can be simple relative to some questions and complex relative to others.

Critics have argued that Sober’s measure produces a number of counter-intuitive results. Firstly, the measure cannot explain why people tend to judge an equation such as y = 3x + 4x2 – 50 as more complex than an equation like y = 2x, relative to the question, “what is the value of y?” In both cases, one only needs a value of x to work out a value for y. Similarly, Sober’s measure fails to deal with Goodman’s above cited counter-example to the idea that simplicity equates to testability, since it produces the counter-intuitive outcome that there is no difference in simplicity between “all maple trees whatsoever, and all sassafras trees in Eagleville, are deciduous” and “all maple trees are deciduous” relative to questions about whether maple trees are deciduous. The interest-relativity of Sober’s measure has also generated criticism from those who prefer to see simplicity as a property that varies only with what a given theory is being compared with, not with the question that one happens to be asking.

e. Thagard’s Measure

Paul Thagard (1988) proposed that simplicity ought to be understood as a ratio of the number of facts explained by a theory to the number of auxiliary assumptions that the theory requires. Thagard defines an auxiliary assumption as a statement, not part of the original theory, which is assumed in order for the theory to be able to explain one or more of the facts to be explained. Simplicity is then measured as follows:

- Simplicity of T = (Facts explained by T – Auxiliary assumptions of T) / Facts explained by T

A value of 0 is given to a maximally complex theory that requires as many auxiliary assumptions as facts that it explains and 1 to a maximally simple theory that requires no auxiliary assumptions at all to explain. Thus, the higher the ratio of facts explained to auxiliary assumptions, the simpler the theory. The essence of Thagard’s proposal is that we want to explain as much as we can, while making the fewest assumptions about the way the world is. By balancing the paucity of auxiliary assumptions against explanatory power it prevents the unfortunate consequence of the simplest theories turning out to be those that are most anaemic.

A significant difficulty facing Thargard’s proposal lies in determining what the auxiliary assumptions of theories actually are and how to count them. It could be argued that the problem of counting auxiliary assumptions threatens to become as difficult as the original problem of measuring simplicity. What a theory must assume about the world for it to explain the evidence is frequently extremely unclear and even harder to quantify. In addition, some auxiliary assumptions are bigger and more onerous than others and it is not clear that they should be given equal weighting, as they are in Thagard’s measure. Another objection is that Thagard’s proposal struggles to make sense of things like ontological parsimony—the idea that theories are simpler because they posit fewer things—since it is not clear that parsimony per se would make any particular difference to the number of auxiliary assumptions required. In defense of this, Thagard has argued that ontological parsimony is actually less important to practicing scientists than has often been thought.

f. Information-Theoretic Measures

Over the last few decades, a number of formal measures of simplicity and complexity have been developed in mathematical information theory. Though many of these measures have been designed for addressing specific practical problems, the central ideas behind them have been claimed to have significance for addressing the philosophical problem of measuring the simplicity of scientific theories.

One of the prominent information-theoretic measures of simplicity in the current literature is Kolmogorov complexity, which is a formal measure of quantitative information content (see Li and Vitányi, 1997). The Kolmogorov complexity K(x) of an object x is the length in bits of the shortest binary program that can output a completely faithful description of x in some universal programming language, such as Java, C++, or LISP. This measure was originally formulated to measure randomness in data strings (such as sequences of numbers), and is based on the insight that non-random data strings can be “compressed” by finding the patterns that exist in them. If there are patterns in a data string, it is possible to provide a completely accurate description of it that is shorter than the string itself, in terms of the number of “bits” of information used in the description, by using the pattern as a mnemonic that eliminates redundant information that need not be encoded in the description. For instance, if the data string is an ordered sequence of 1s and 0s, where every 1 is followed by a 0, and every 0 by a 1, then it can be given a very short description that specifies the pattern, the value of the first data point and the number of data points. Any further information is redundant. Completely random data sets, however, contain no patterns, no redundancy, and hence are not compressible.