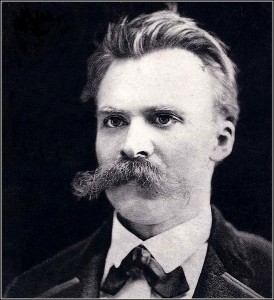

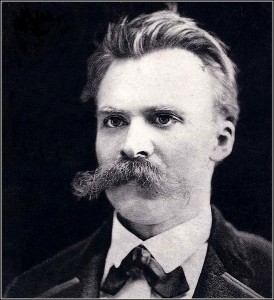

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844—1900)

Nietzsche was a German philosopher, essayist, and cultural critic. His writings on truth, morality, language, aesthetics, cultural theory, history, nihilism, power, consciousness, and the meaning of existence have exerted an enormous influence on Western philosophy and intellectual history.

Nietzsche was a German philosopher, essayist, and cultural critic. His writings on truth, morality, language, aesthetics, cultural theory, history, nihilism, power, consciousness, and the meaning of existence have exerted an enormous influence on Western philosophy and intellectual history.

Nietzsche spoke of “the death of God,” and foresaw the dissolution of traditional religion and metaphysics. Some interpreters of Nietzsche believe he embraced nihilism, rejected philosophical reasoning, and promoted a literary exploration of the human condition, while not being concerned with gaining truth and knowledge in the traditional sense of those terms. However, other interpreters of Nietzsche say that in attempting to counteract the predicted rise of nihilism, he was engaged in a positive program to reaffirm life, and so he called for a radical, naturalistic rethinking of the nature of human existence, knowledge, and morality. On either interpretation, it is agreed that he suggested a plan for “becoming what one is” through the cultivation of instincts and various cognitive faculties, a plan that requires constant struggle with one’s psychological and intellectual inheritances.

Nietzsche claimed the exemplary human being must craft his/her own identity through self-realization and do so without relying on anything transcending that life—such as God or a soul. This way of living should be affirmed even were one to adopt, most problematically, a radical vision of eternity, one suggesting the “eternal recurrence” of all events. According to some commentators, Nietzsche advanced a cosmological theory of “will to power.” But others interpret him as not being overly concerned with working out a general cosmology. Questions regarding the coherence of Nietzsche’s views–questions such as whether these views could all be taken together without contradiction, whether readers should discredit any particular view if proven incoherent or incompatible with others, and the like–continue to draw the attention of contemporary intellectual historians and philosophers.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Periodization of Writings

- Problems of Interpretation

- Nihilism and the Revaluation of Values

- The Human Exemplar

- Will to Power

- Eternal Recurrence

- Reception of Nietzsche’s Thought

- References and Further Reading

- Nietzsche’s Collected Works in German

- Nietzsche’s Major Works Available in English

- Important Works Available in English from Nietzsche’s Nachlass

- Biographies

- Commentaries and Scholarly Researches

- Academic Journals in Nietzsche Studies

1. Life

Because much of Nietzsche’s philosophical work has to do with the creation of self—or to put it in Nietzschean terms, “becoming what one is”— some scholars exhibit uncommon interest in the biographical anecdotes of Nietzsche’s life. Taking this approach, however, risks confusing aspects of the Nietzsche legend with what is important in his philosophical work, and many commentators are rightly skeptical of readings derived primarily from biographical anecdotes.

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was born October 15, 1844, the son of Karl Ludwig and Franziska Nietzsche. Karl Ludwig Nietzsche was a Lutheran Minister in the small Prussian town of Röcken, near Leipzig. When young Friedrich was not quite five, his father died of a brain hemorrhage, leaving Franziska, Friedrich, a three-year old daughter, Elisabeth, and an infant son. Friedrich’s brother died unexpectedly shortly thereafter (reportedly, the legend says, fulfilling Friedrich’s dream foretelling of the tragedy). These events left young Friedrich the only male in a household that included his mother, sister, paternal grandmother and an aunt, although Friedrich drew upon the paternal guidance of Franziska’s father. Young Friedrich also enjoyed the camaraderie of a few male playmates.

Upon the loss of Karl Ludwig, the family took up residence in the relatively urban setting of Naumburg, Saxony. Friedrich gained admittance to the prestigious Schulpforta, where he received Prussia’s finest preparatory education in the Humanities, Theology, and Classical Languages. Outside school, Nietzsche founded a literary and creative society with classmates including Paul Deussen (who was later to become a prominent scholar of Sanskrit and Indic Studies). In addition, Nietzsche played piano, composed music, and read the works of Emerson and the poet Friedrich Hölderlin, who was relatively unknown at the time.

In 1864 Nietzsche entered the University of Bonn, spending the better part of that first year unproductively, joining a fraternity and socializing with old and new acquaintances, most of whom would fall out of his life once he regained his intellectual focus. By this time he had also given up Theology, dashing his mother’s hopes of a career in the ministry for him. Instead, he choose the more humanistic study of classical languages and a career in Philology. In 1865 he followed his major professor, Friedrich Ritschl, from Bonn to the University of Leipzig and dedicated himself to the studious life, establishing an extracurricular society there devoted to the study of ancient texts. Nietzsche’s first contribution to this group was an essay on the Greek poet, Theognis, and it drew the attention of Professor Ritschl, who was so impressed that he published the essay in his academic journal, Rheinisches Museum. Other published writings by Nietzsche soon followed, and by 1868 (after a year of obligatory service in the Prussian military), young Friedrich was being promoted as something of a “phenomenon” in classical scholarship by Ritschl, whose esteem and praise landed Nietzsche a position as Professor of Greek Language and Literature at the University of Basel in Switzerland, even though the candidate had not yet begun writing his doctoral dissertation. The year was 1869 and Friedrich Nietzsche was 24 years old.

At this point in his life, however, Nietzsche was a far cry from the original thinker he would later become, since neither he nor his work had matured. Swayed by public opinion and youthful exuberance, he briefly interrupted teaching in 1870 to join the Prussian military, serving as a medical orderly at the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. His service was cut short, however, by severe bouts of dysentery and diphtheria. Back in Basel, his teaching responsibilities at the University and a nearby Gymnasium consumed much of his intellectual and physical energy. He became acquainted with the prominent cultural historian, Jacob Burkhardt, a well-established member of the university faculty. But, the person exerting the most influence on Nietzsche at this point was the artist, Richard Wagner, whom Nietzsche had met while studying in Leipzig. During the first half of the decade, Wagner and his companion, Cosima von Bülow, frequently entertained Nietzsche at Triebschen, their residence near Lake Lucerne, and then later at Bayreuth.

It is commonplace to say that at one time Nietzsche looked to Wagner with the admiration of a dutiful son. This interpretation of their relationship is supported by the fact that Wagner would have been the same age as Karl Ludwig, had the elder Nietzsche been alive. It is also commonplace to note that Nietzsche was in awe of the artist’s excessive displays of a fiery temperament, bravado, ambition, egoism, and loftiness— typical qualities demonstrating “genius” in the nineteenth century. In short, Nietzsche was overwhelmed by Wagner’s personality. A more mature Nietzsche would later look back on this relationship with some regret, although he never denied the significance of Wagner’s influence on his emotional and intellectual path, Nietzsche’s estimation of Wagner’s work would alter considerably over the course of his life. Nonetheless, in light of this relationship, one can easily detect Wagner’s presence in much of Nietzsche’s early writings, particularly in the latter chapters of The Birth of Tragedy and in the first and fourth essays of 1874’s Untimely Meditations. Also, Wagner’s supervision exerted considerable editorial control over Nietzsche’s intellectual projects, leading him to abandon, for example, 1873’s Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, which Wagner scorned because of its apparent irrelevance to his own work. Such pressures continued to bridle Nietzsche throughout the so-called early period. He broke free of Wagner’s dominance once and for all in 1877, after a series of emotionally charged episodes. Nietzsche’s fallout with Wagner, who had moved to Bayreuth by this time, led to the publication of 1878’s Human, All-Too Human, one of Nietzsche’s most pragmatic and un-romantic texts—the original title page included a dedication to Voltaire and a quote from Descartes. If Nietzsche intended to use this text as a way of alienating himself from the Wagnerian circle, he surely succeeded. Upon its arrival in Bayreuth, the text ended this personal relationship with Wagner.

It would be an exaggeration to say that Nietzsche was not developing intellectually during the period, prior to 1877. In fact, figures other than Wagner drew Nietzsche’s interest and admiration. In addition to attending Burkhardt’s lectures at Basel, Nietzsche studied Greek thought from the Pre-Socratics to Plato, and he learned much about the history of philosophy from Friedrich Albert Lange’s massive History of Materialism, which Nietzsche once called “a treasure trove” of historical and philosophical names, dates, and currents of thought. In addition, Nietzsche was taken by the persona of the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, which Nietzsche claimed to have culled from close readings of the two-volume magnum opus, The World as Will and Representation.

Nietzsche discovered Schopenhauer while studying in Leipzig. Because his training at Schulpforta had elevated him far above most of his classmates, he frequently skipped lectures at Leipzig in order to devote time to [CE1] Schopenhauer’s philosophy. For Nietzsche, the most important aspect of this philosophy was the figure from which it emanated, representing for him the heroic ideal of a man in the life of thought: a near-contemporary thinker participating in that great and noble “republic of genius,” spanning the centuries of free thinking sages and creative personalities. That Nietzsche could not countenance Schopenhauer’s “ethical pessimism” and its negation of the will was recognized by the young man quite early during this encounter. Yet, even in Nietzsche’s attempts to construct a counter-posed “pessimism of strength” affirming the will, much of Schopenhauer’s thought remained embedded in Nietzsche’s philosophy, particularly during the early period. Nietzsche’s philosophical reliance on “genius”, his cultural-political visions of rank and order through merit, and his self-described (and later self-rebuked) “metaphysics of art” all had Schopenhauerian underpinnings. Also, Birth of Tragedy’s well-known dualism between the cosmological/aesthetic principles of Dionysus and Apollo, contesting and complimenting each other in the tragic play of chaos and order, confusion and individuation, strikes a familiar chord to readers acquainted with Schopenhauer’s description of the world as “will” and “representation.”

Despite these similarities, Nietzsche’s philosophical break with Schopenhauerian pessimism was as real as his break with Wagner’s domineering presence was painful. Ultimately, however, such triumphs were necessary to the development and liberation of Nietzsche as thinker, and they proved to be instructive as Nietzsche later thematized the importance of “self-overcoming” for the project of cultivating a free spirit.

The middle and latter part of the 1870s was a time of great upheaval in Nietzsche’s personal life. In addition to the turmoil with Wagner and related troubles with friends in the artist’s circle of admirers, Nietzsche suffered digestive problems, declining eyesight, migraines, and a variety of physical aliments, rendering him unable to fulfill responsibilities at Basel for months at a time. After publication of Birth of Tragedy, and despite its perceived success in Wagnerian circles for trumpeting the master’s vision for Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (“The Art Work of the Future”) Nietzsche’s academic reputation as a philologist was effectively destroyed due in large part to the work’s apparent disregard for scholarly expectations characteristic of nineteenth-century philology. Birth of Tragedy was mocked as Zukunfts-Philologie (“Future Philology”) by Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, an up-and-coming peer destined for an illustrious career in Classicism, and even Ritschl characterized it as a work of “megalomania.” For these reasons, Nietzsche had difficulty attracting students. Even before the publication of Birth of Tragedy, he had attempted to re-position himself at Basel in the department of philosophy, but the University apparently never took such an endeavor seriously. By 1878, his circumstances at Basel deteriorated to the point that neither the University nor Nietzsche was very much interested in seeing him continue as a professor there, so both agreed that he should retire with a modest pension [CE2] . He was 34 years old and now apparently liberated, not only from his teaching duties and the professional discipline he grew to despise, but also from the emotional and intellectual ties that dominated him during his youth. His physical woes, however, would continue to plague him for the remainder of his life.

After leaving Basel, Nietzsche enjoyed a period of great productivity. And, during this time, he was never to stay in one place for long, moving with the seasons, in search of relief for his ailments, solitude for his work, and reasonable living conditions, given his very modest budget. He often spent summers in the Swiss Alps in Sils Maria, near St. Moritz, and winters in Genoa, Nice, or Rappollo on the Mediterranean coast. Occasionally, he would visit family and friends in Naumburg or Basel, and he spent a great deal of time in social discourse, exchanging letters with friends and associates.

In the latter part of the 1880s, Nietzsche’s health worsened, and in the midst of an amazing flourish of intellectual activity which produced On the Genealogy of Morality, Twilight of the Idols, The Anti-Christ, and several other works (including preparation for what was intended to be his magnum opus, a work that editors later titled Will to Power) Nietzsche suffered a complete mental and physical breakdown. The famed moment at which Nietzsche is said to have succumbed irrevocably to his ailments occurred January 3, 1889 in Turin (Torino) Italy, reportedly outside Nietzsche’s apartment in the Piazza Carlos Alberto while embracing a horse being flogged by its owner.

After spending time in psychiatric clinics in Basel and Jena, Nietzsche was first placed in the care of his mother, and then later his sister (who had spent the latter half of the 1880’s attempting to establish a “racially pure” German colony in Paraguay with her husband, the anti-Semitic political opportunist Bernhard Foerster). By the early 1890s, Elisabeth had seized control of Nietzsche’s literary remains, which included a vast amount of unpublished writings. She quickly began shaping his image and the reception of his work, which by this time had already gained momentum among academics such as Georg Brandes. Soon the Nietzsche legend would grow in spectacular fashion among popular readers. From Villa Silberblick, the Nietzsche home in Weimar, Elisabeth and her associates managed Friedrich’s estate, editing his works in accordance with her taste for a populist decorum and occasionally with an ominous political intent that (later researchers agree) corrupted the original thought[CE3] . Unfortunately, Friedrich experienced little of his fame, having never recovered from the breakdown of late 1888 and early 1889. His final years were spent at Villa Silberblick in grim mental and physical deterioration, ending mercifully August 25, 1900. He was buried in Röcken, near Leipzig. Elisabeth spent one last year in Paraguay in 1892-93 before returning to Germany, where she continued to exert influence over the perception of Nietzsche’s work and reputation, particularly among general readers, until her death in 1935. Villa Silberblick stands today as a monument, of sorts, to Friedrich and Elisabeth, while the bulk of Nietzsche’s literary remains is held in the Goethe-Schiller Archiv, also in Weimar.

2. Periodization of Writings

Nietzsche scholars commonly divide his work into periods, usually with the implication that discernable shifts in Nietzsche’s circumstances and intellectual development justify some form of periodization in the corpus. The following division is typical:

(i.) before 1869—the juvenilia

Cautious Nietzsche biographers work to separate the facts of Nietzsche’s life from myth, and while a major part of the Nietzsche legend holds that Friedrich was a precocious child, writings from his youth bear witness to that part of the story. During this time Nietzsche was admitted into the prestigious Gymnasium Schulpforta; he composed music, wrote poetry and plays, and in 1863 produced an autobiography (at the age of 19). He also produced more serious and accomplished works on themes related to philology, literature, and philosophy. By 1866 he had begun contributing articles to a major philological journal, Rheinisches Museum, edited by Nietzsche’s esteemed professor at Bonn and Leipzig, Friedrich Ritschl. With Ritschl’s recommendation, Nietzsche was appointed professor of Greek Language and Literature at the University of Basel in January 1869.

(ii.) 1869-1876–the early period

Nietzsche’s writings during this time reflect interests in philology, cultural criticism, and aesthetics. His inaugural public lecture at Basel in May 1869, “Homer and Classical Philology” brought out aesthetic and scientific aspects of his discipline, portending Nietzsche’s attitudes towards science, art, philology and philosophy. He was influenced intellectually by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and emotionally by the artist Richard Wagner. Nietzsche’s first published book, The Birth of Tragedy, appropriated Schopenhaurian categories of individuation and chaos in an elucidation of primordial aesthetic drives represented by the Greek gods Apollo and Dionysus. This text also included a Wagnerian precept for cultural flourishing: society must cultivate and promote its most elevated and creative types—the artistic genius. In the Preface to a later edition of this work, Nietzsche expresses regret for having attempted to elaborate a “metaphysics of art.” In addition to these themes, Nietzsche’s interest during this period extended to Greek philosophy, intellectual history, and the natural sciences, all of which were significant to the development of his mature thought. Nietzsche’s second book-length project, The Untimely Meditations, contains four essays written from 1873-1876. It is a work of acerbic cultural criticism, encomia to Schopenhauer and Wagner, and an unexpectedly idiosyncratic analysis of the newly developing historical consciousness. A fifth meditation on the discipline of philology is prepared but left unpublished. Plagued by poor health, Nietzsche is released from teaching duties in February 1876 (his affiliation with the university officially ends in 1878 and he is granted a small pension).

(iii.) 1877-1882—the middle period

During this time Nietzsche liberated himself from the emotional grip of Wagner and the artist’s circle of admirers, as well as from those ideas which (as he claims in Ecce Homo) “did not belong” to him in his “nature” (“Human All Too Human: With Two Supplements” 1). Reworking earlier themes such as tragedy in philosophy, art and truth, and the human exemplar, Nietzsche’s thinking now comes into sharper focus, and he sets out on a philosophical path to be followed the remainder of his productive life. In this period’s three published works Human, All-Too Human (1878-79), Dawn (1881), and The Gay Science (1882), Nietzsche takes up writing in an aphoristic style, which permits exploration of a variety of themes. Most importantly, Nietzsche lays out a plan for “becoming what one is” through the cultivation of instincts and various cognitive faculties, a plan that requires constant struggle with one’s psychological and intellectual inheritances. Nietzsche discovers that “one thing is needful” for the exemplary human being: to craft an identity from otherwise dissociated events bringing forth the horizons of one’s existence. Self-realization, as it is conceived in these texts, demands the radicalization of critical inquiry with a historical consciousness and then a “retrograde step” back (Human aphorism 20) from what is revealed in such examinations, insofar as these revelations threaten to dissolve all metaphysical realities and leave nothing but the abysmal comedy of existence. A peculiar kind of meaningfulness is thus gained by the retrograde step: it yields a purpose for existence, but in an ironic form, perhaps esoterically and without ground; it is transparently nihilistic to the man with insight, but suitable for most; susceptible to all sorts of suspicion, it is nonetheless necessary and for that reason enforced by institutional powers. Nietzsche calls the one who teaches the purpose of existence a “tragic hero” (GS 1), and the one who understands the logic of the retrograde step a “free spirit.” Nietzsche’s account of this struggle for self-realization and meaning leads him to consider problems related to metaphysics, religion, knowledge, aesthetics, and morality.

(iv.) Post-1882—the later period

Nietzsche transitions into a new period with the conclusion of The Gay Science (Book IV) and his next published work, the novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra, produced in four parts between 1883 and 1885. Also in 1885 he returns to philosophical writing with Beyond Good and Evil. In 1886 he attempts to consolidate his inquiries through self-criticism in Prefaces written for the earlier published works, and he writes a fifth book for The Gay Science. In 1887 he writes On the Genealogy of Morality. In 1888, with failing health, he produces several texts, including The Twilight of the Idols, The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, and two works concerning his prior relationship with Wagner. During this period, as with the earlier ones, Nietzsche produces an abundance of materials not published during his lifetime. These works constitute what is referred to as Nietzsche’s Nachlass. (For years this material has been published piecemeal in Germany and translated to English in various collections.) Philosophically, during this period, Nietzsche continues his explorations on morality, truth, aesthetics, history, power, language and identity. For some readers, he appears to be broadening the scope of his ideas to work out a cosmology involving the all encompassing “will to power” and the curiously related and enigmatic “eternal recurrence of the same.” Prior claims regarding the retrograde step are re-thought, apparently in favor of seeking some sort of breakthrough into the “abyss of light” (Zarathustra’s “Before Sunrise”) or in an encounter with “decadence” (“Expeditions of a Untimely Man” 43, in Twilight of the Idols). The intent here seems to be an overcoming or dissolution of metaphysics. These developments are matters of contention, however, as some commentators maintain that statements regarding Nietzsche’s “cosmological vision” are exaggerated. And, some will even deny that he achieves (nor even attempts) the overcoming described above. Despite such complaints, interpreters of Nietzsche continue to reference these ineffable concepts.

3. Problems of Interpretation

Nietzsche’s work in the beginning was heavily influenced, either positively or negatively, by the events of his young life. His early and on-going interest in the Greeks, for example, can be attributed in part to his Classical education at Schulpforta, for which he was well-prepared as a result of his family’s attempts to steer him into the ministry. Nietzsche’s intense association with Wagner no doubt enhanced his orientation towards the philosophy of Schopenhauer, and it probably promoted his work in aesthetics and cultural criticism. These biographical elements came to bear on Nietzsche’s first major works, while the middle period amounts to a confrontation with many of these influences. In Nietzsche’s later writings we find the development of concepts that seem less tangibly related to the biographical events of his life.

Let’s outline four of these concepts, but not before adding a word of caution regarding how this outline should be received. Nietzsche asserts in the opening section of Twilight of the Idols that he “mistrusts systematizers” (“Maxims and Arrows” 26), which is taken by some readers to be a declaration of his fundamental stance towards philosophical systems, with the additional inference that nothing resembling such a system must be permitted to stand in interpretations of his thought. Although it would not be illogical to say that Nietzsche mistrusted philosophical systems, while nevertheless building one of his own, some commentators point out two important qualifications. First, the meaning of Nietzsche’s stated “mistrust” in this brief aphorism can and should be treated with caution. In Beyond Good and Evil Nietzsche claims that philosophers today, after millennia of dogmatizing about absolutes, now have a “duty to mistrust” philosophy’s dogmatizing tendencies (BGE 34). Yet, earlier in that same text, Nietzsche claimed that all philosophical interpretations of nature are acts of will power (BGE 9) and that his interpretations are subject to the same critique (BGE 22). In Thus Spoke Zarathustra’s “Of Involuntary Bliss” we find Zarathustra speaking of his own “mistrust,” when he describes the happiness that has come to him in the “blissful hour” of the third part of that book. Zarathustra attempts to chase away this bliss while waiting for the arrival of his unhappiness, but his happiness draws “nearer and nearer to him,” because he does not chase after it. In the next scene we find Zarathustra dwelling in the “light abyss” of the pure open sky, “before sunrise.” What then is the meaning of this “mistrust”? At the very least, we can say that Nietzsche does not intend it to establish a strong and unmovable absolute, a negative-system, from which dogma may be drawn. Nor, possibly, is Nietzsche’s mistrust of systematizers absolutely clear. Perhaps it is a discredit to Nietzsche as a philosopher that he did not elaborate his position more carefully within this tension; or, perhaps such uncertainty has its own ground. Commentators such as Mueller-Lauter have noticed ambivalence in Nietzsche’s work on this very issue, and it seems plausible that Nietzsche mistrusted systems while nevertheless constructing something like a system countenancing this mistrust. He says something akin to this, after all, in Beyond Good and Evil, where it is claimed that even science’s truths are matters of interpretation, while admitting that this bold claim is also an interpretation and “so much the better” (aphorism 22). For a second cautionary note, many commentators will argue along with Richard Schacht that, instead of building a system, Nietzsche is concerned only with the exploration of problems, and that his kind of philosophy is limited to the interpretation and evaluation of cultural inheritances (1995). Other commentators will attempt to complement this sort of interpretation and, like Löwith, presume that the ground for Nietzsche’s explorations may also be examined. Löwith and others argue that this ground concerns Nietzsche’s encounter with historical nihilism. The following outline should be received, then, with the understanding that Nietzsche’s own iconoclastic nature, his perspectivism, and his life-long projects of genealogical critique and the revaluation of values, lend credence to those anti-foundational readings which seek to emphasize only those exploratory aspects of Nietzsche’s work while refuting even implicit submissions to an orthodox interpretation of “the one Nietzsche” and his “one system of thought.” With this caution, the following outline is offered as one way of grounding Nietzsche’s various explorations.

The four major concepts presented in this outline are:

- (i) Nihilism and the Revaluation of Values, which is embodied by a historical event, “the death of God,” and which entails, somewhat problematically, the project of transvaluation;

- (ii) The Human Exemplar, which takes many forms in Nietzsche’s thought, including the “tragic artist”, the “sage”, the “free spirit”, the “philosopher of the future”, the Übermensch (variously translated in English as “Superman,” “Overman,” “Overhuman,” and the like), and perhaps others (the case could be made, for example, that in Nietzsche’s notoriously self-indulgent and self-congratulatory Ecce Homo, the role of the human exemplar is played by “Mr. Nietzsche” himself);

- (iii) Will to Power (Wille zur Macht), from a naturalized history of morals and truth developing through subjective feelings of power to a cosmology;

- (iv) Eternal Recurrence or Eternal Return (variously in Nietzsche’s work, “die ewige Wiederkunft” or “die ewige Wiederkehr”) of the Same (des Gleich), a solution to the riddle of temporality without purpose.

4. Nihilism and the Revaluation of Values

Although Michael Gillespie makes a strong case that Nietzsche misunderstood nihilism, and in any event Nietzsche’s Dionysianism would be a better place to look for an anti-metaphysical breakthrough in Nietzsche’s corpus (1995, 178), commentators as varied in philosophical orientation as Heidegger and Danto have argued that nihilism is a central theme in Nietzsche’s philosophy. Why is this so? The constellation of Nietzsche’s fundamental concepts moves within his general understanding of modernity’s historical situation in the late nineteenth century. In this respect, Nietzsche’s thought carries out the Kantian project of “critique” by applying the nineteenth century’s developing historical awareness to problems concerning the possibilities of knowledge, truth, and human consciousness. Unlike Kant’s critiques, Nietzsche’s examinations find no transcendental ego, given that even the categories of experience are historically situated and likewise determined. Unlike Hegel’s notion of historical consciousness, however, history for Nietzsche has no inherent teleology. All beginnings and ends, for Nietzsche, are thus lost in a flood of indeterminacy. As early as 1873, Nietzsche was arguing that human reason is only one of many peculiar developments in the ebb and flow of time, and when there are no more rational animals nothing of absolute value will have transpired (“On truth and lies in a non-moral sense”). Some commentators would prefer to consider these sorts of remarks as belonging to Nietzsche’s “juvenilia.” Nevertheless, as late as 1888’s “Reason in Philosophy” from Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche derides philosophers who would make a “fetish” out of reason and retreat into the illusion of a “de-historicized” world. Such a philosopher is “decadent,” symptomatic of a “declining life”. Opposed to this type, Nietzsche valorizes the “Dionysian” artist whose sense of history affirms “all that is questionable and terrible in existence.”

Nietzsche’s philosophy contemplates the meaning of values and their significance to human existence. Given that no absolute values exist, in Nietzsche’s worldview, the evolution of values on earth must be measured by some other means. How then shall they be understood? The existence of a value presupposes a value-positing perspective, and values are created by human beings (and perhaps other value-positing agents) as aids for survival and growth. Because values are important for the well being of the human animal, because belief in them is essential to our existence, we oftentimes prefer to forget that values are our own creations and to live through them as if they were absolute. For these reasons, social institutions enforcing adherence to inherited values are permitted to create self-serving economies of power, so long as individuals living through them are thereby made more secure and their possibilities for life enhanced. Nevertheless, from time to time the values we inherit are deemed no longer suitable and the continued enforcement of them no longer stands in the service of life. To maintain allegiance to such values, even when they no longer seem practicable, turns what once served the advantage to individuals to a disadvantage, and what was once the prudent deployment of values into a life denying abuse of power. When this happens the human being must reactivate its creative, value-positing capacities and construct new values.

Commentators will differ on the question of whether nihilism for Nietzsche refers specifically to a state of affairs characterizing specific historical moments, in which inherited values have been exposed as superstition and have thus become outdated, or whether Nietzsche means something more than this. It is, at the very least, accurate to say that for Nietzsche nihilism has become a problem by the nineteenth century. The scientific, technological, and political revolutions of the previous two hundred years put an enormous amount of pressure on the old world order. In this environment, old value systems were being dismantled under the weight of newly discovered grounds for doubt. The possibility arises, then, that nihilism for Nietzsche is merely a temporary stage in the refinement of true belief. This view has the advantage of making Nietzsche’s remarks on truth and morality seem coherent from a pragmatic standpoint, in that with this view the problem of nihilism is met when false beliefs have been identified and corrected. Reason is not a value, in this reading, but rather the means by which human beings examine their metaphysical presuppositions and explore new avenues to truth.

Yet, another view will have it that by nihilism Nietzsche is pointing out something even more unruly at work, systemically, in the Western world’s axiomatic orientation. Heidegger, for example, claims that with the problem of nihilism Nietzsche is showing us the essence of Western metaphysics and its system of values (“The Word of Nietzsche: ‘God is dead’”). According to this view, Nietzsche’s philosophy of value, with its emphasis on the value-positing gesture, implies that even the concept of truth in the Western worldview leads to arbitrary determinations of value and political order and that this worldview is disintegrating under the weight of its own internal logic (or perhaps “illogic”). In this reading, the history of truth in the occidental world is the “history of an error” (Twilight of the Idols), harboring profoundly disruptive antinomies which lead, ultimately, to the undoing of the Western philosophical framework. This kind of systemic flaw is exposed by the historical consciousness of the nineteenth century, which makes the problem of nihilism seem all the more acutely related to Nietzsche’s historical situation. But to relegate nihilism to that situation, according to Heidegger, leaves our thinking of it incomplete.

Heidegger makes this stronger claim with the aid of Nietzsche’s Nachlass. Near the beginning of the aphorisms collected under the title, Will To Power (aphorism 2), we find this note from 1887: “What does nihilism mean? That the highest values devalue themselves. The aim is lacking; ‘Why?’ finds no answer.” Here, Nietzsche’s answer regarding the meaning of nihilism has three parts.

(i) The first part makes a claim about the logic of values: ultimately, given the immense breadth of time, even “the highest values devalue themselves.” What does this mean? According to Nietzsche, the conceptual framework known as Western metaphysics was first articulated by Plato, who had pieced together remnants of a declining worldview, borrowing elements from predecessors such as Anaximander, Parmenides, and especially Socrates, in order to overturn a cosmology that had been in play from the days of Homer and which found its fullest and last expression in the thought of Heraclitus. Plato’s framework was popularized by Christianity, which added egalitarian elements along with the virtue of pity. The maturation of Western metaphysics occurs during modernity’s scientific and political revolutions, wherein the effects of its inconsistencies, malfunctions, and mal-development become acute. At this point, according to Nietzsche, “the highest values devalue themselves,” as modernity’s striving for honesty, probity, and courage in the search for truth, those all-important virtues inhabiting the core of scientific progress, strike a fatal blow against the foundational idea of absolutes. Values most responsible for the scientific revolution, however, are also crucial to the metaphysical system that modern science is destroying. Such values are threatening, then, to bring about the destruction of their own foundations. Thus, the highest values are devaluing themselves at the core. Most importantly, the values of honesty, probity, and courage in the search for truth no longer seem compatible with the guarantee, the bestowal, and the bestowing agent of an absolute value. Even the truth of “truth” now falls prey to the workings of nihilism, given that Western metaphysics now appears groundless in this logic.

For some commentators, this line of interpretation leaves Nietzsche’s revaluation of values lost in contradiction. What philosophical ground, after all, could support revaluation if this interpretation were accurate? For this reason, readers such as Clark work to establish a coherent theory of truth in Nietzsche’s philosophy, which can apparently be done by emphasizing various parts of the corpus to the exclusion of others. If, indeed, a workable epistemology may be derived from reading specific passages, and good reasons can be given for prioritizing those passages, then consistent grounds may exist for Nietzsche having leveled a critique of morality. Such readings, however, seem incompatible with Nietzsche’s encounter with historical nihilism, unless nihilism is taken to represent merely a temporary stage in the refinement of Western humanity’s acquisition of knowledge.

With the stronger claim, however, Nietzsche’s critique of the modern situation implies that the “highest values [necessarily] devalue themselves.” Western metaphysics brings about its own disintegration, in working out the implications of its inner logic. Nietzsche’s name for this great and terrible event, capturing popular imagination with horror and disgust, is the “death of God.” Nietzsche acknowledges that a widespread understanding of this event, the “great noon” at which all “shadows of God” will be washed out, is still to come. In Nietzsche’s day, the God of the old metaphysics is still worshiped, of course, and would be worshiped, he predicted, for years to come. But, Nietzsche insisted, in an intellectual climate that demands honesty in the search for truth and proof as a condition for belief, the absence of foundations has already been laid bare. The dawn of a new day had broken, and shadows now cast, though long, were receding by the minute.

(ii) The second part of the answer to the question concerning nihilism states that “the aim is lacking.” What does this mean? In Beyond Good and Evil Nietzsche claims that the logic of an existence lacking inherent meaning demands, from an organizational standpoint, a value-creating response, however weak this response might initially be in comparison to how its values are then taken when enforced by social institutions (aphorisms 20-23). Surveys of various cultures show that humanity’s most indispensable creation, the affirmation of meaning and purpose, lies at the heart of all fundamental values. Nihilism stands not only for that apparently inevitable process by which the highest values devalue themselves. It also stands for that moment of recognition in which human existence appears, ultimately, to be in vain. Nietzsche’s surveys of cultures and their values, his cultural anthropologies, are typically reductive in the extreme, attempting to reach the most important sociopolitical questions as neatly and quickly as possible. Thus, when examining so-called Jewish, Oriental, Roman, or Medieval European cultures Nietzsche asks, “how was meaning and purpose proffered and secured here? How, and for how long, did the values here serve the living? What form of redemption was sought here, and was this form indicative of a healthy life? What may one learn about the creation of values by surveying such cultures?” This version of nihilism then means that absolute aims are lacking and that cultures naturally attempt to compensate for this absence with the creation of goals.

(iii) The third part of the answer to the question concerning nihilism states that “‘why?’ finds no answer.” Who is posing the question here? Emphasis is laid on the one who faces the problem of nihilism. The problem of value-positing concerns the one who posits values, and this one must be examined, along with a corresponding evaluation of relative strengths and weaknesses. When, indeed, “why?” finds no answer, nihilism is complete. The danger here is that the value-positing agent might become paralyzed, leaving the call of life’s most dreadful question unanswered. In regards to this danger, Nietzsche’s most important cultural anthropologies examined the Greeks from Homer to the age of tragedy and the “pre-Platonic” philosophers. Here was evidence, Nietzsche believed, that humanity could face the dreadful truth of existence without becoming paralyzed. At every turn, the moment in which the Greek world’s highest values devalued themselves, when an absolute aim was shown to be lacking, the question “why?” nevertheless called forth an answer. The strength of Greek culture is evident in the gods, the tragic art, and the philosophical concepts and personalities created by the Greeks themselves. Comparing the creativity of the Greeks to the intellectual work of modernity, the tragic, affirmative thought of Heraclitus to the pessimism of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche highlights a number of qualitative differences. Both types are marked by the appearance of nihilism, having been drawn into the inevitable logic of value-positing and what it would seem to indicate. The Greek type nevertheless demonstrates the characteristics of strength by activating and re-intensifying the capacity to create, by overcoming paralysis, by willing a new truth, and by affirming the will. The other type displays a pessimism of weakness, passivity, and weariness—traits typified by Schopenhauer’s life-denying ethics of the will turning against itself. In Nietzsche’s 1888 retrospection on the Birth of Tragedy in Ecce Homo, we read that “Hellenism and Pessimism” would have made a more precise title for the first work, because Nietzsche claims to have attempted to demonstrate how

the Greeks got rid of pessimism—with what they overcame it….Precisely tragedy is the proof that the Greeks were no pessimists: Schopenhauer blundered in this as he blundered in everything (“The Birth of Tragedy” in Ecce Homo section 1).

From Twilight of the Idols, also penned during that sublime year of 1888, Nietzsche writes that tragedy “has to be considered the decisive repudiation” of pessimism as Schopenhauer understood it:

affirmation of life, even in its strangest and sternest problems, the will to life rejoicing in its own inexhaustibility through the sacrifice of its highest types—that is what I called Dionysian….beyond [Aristotelian] pity and terror, to realize in oneself the eternal joy of becoming—that joy which also encompasses joy in destruction (“What I Owe the Ancients” 5).

Nietzsche concludes the above passage by claiming to be the “last disciple of the philosopher Dionysus” (which by this time in Nietzsche’s thought came to encompass the whole of that movement which formerly distinguished between Apollo and Dionysus). Simultaneously, Nietzsche declares himself, with great emphasis, to be the “teacher of the eternal recurrence.”

The work to overcome pessimism is tragic in a two-fold sense: it maintains a feeling for the absence of ground, while responding to this absence with the creation of something meaningful. This work is also unmodern, according to Nietzsche, since modernity either has yet to ask the question “why?,” in any profound sense or, in those cases where the question has been posed, it has yet to come up with a response. Hence, a pessimism of weakness and an incomplete form of nihilism prevail in the modern epoch. Redemption in this life is denied, while an uncompleted form of nihilism remains the fundamental condition of humanity. Although the logic of nihilism seems inevitable, given the absence of absolute purpose and meaning, “actively” confronting nihilism and completing our historical encounter with it will be a sign of good health and the “increased power of the spirit” (Will to Power aphorism 22). Thus far, however, modernity’s attempts to “escape nihilism” (in turning away) have only served to “make the problem more acute” (aphorism 28). Why, then, this failure? What does modernity lack?

5. The Human Exemplar

How and why do nihilism and the pessimism of weakness prevail in modernity? Again, from the notebook of 1887 (Will to Power, aphorism 27), we find two conditions for this situation:

1. the higher species is lacking, i.e., those whose inexhaustible fertility and power keep up the faith in man….[and] 2. the lower species (‘herd,’ ‘mass,’ ‘society,’) unlearns modesty and blows up its needs into cosmic and metaphysical values. In this way the whole of existence is vulgarized: insofar as the mass is dominant it bullies the exceptions, so they lose their faith in themselves and become nihilists.

With the fulfillment of “European nihilism” (which is no doubt, for Nietzsche, endemic throughout the Western world and anyplace touched by “modernity”), and the death of otherworldly hopes for redemption, Nietzsche imagines two possible responses: the easy response, the way of the “herd” and “the last man,” or the difficult response, the way of the “exception,” and the Übermensch.

Ancillary to any discussion of the exception, per se, the compatibility of the Übermensch concept with other movements in Nietzsche’s thought, and even the significance that Nietzsche himself placed upon it, has been the subject of intense debate among Nietzsche scholars. The term’s appearance in Nietzsche’s corpus is limited primarily to Thus Spoke Zarathustra and works directly related to this text. Even here, moreover, the Übermensch is only briefly and very early announced in the narrative, albeit with a tremendous amount of fanfare, before fading from explicit consideration. In addition to these problems, there are debates concerning the basic nature of the Übermensch itself, whether “Über-” refers to a transitional movement or a transmogrified state of being, and whether Nietzsche envisioned the possibility of a community of Übermenschen, as opposed to a solitary figure among lesser types. So, what should be made of Nietzsche’s so-called “overman” (or even “superman”) called upon to arrive after the “death of God”?

Whatever else may be said about the Übermensch, Nietzsche clearly had in mind an exemplary figure and an exception among humans, one “whose inexhaustible fertility and power keep up the faith in man.” For some commentators, Nietzsche’s distinction between overman and the last man has political ramifications. The hope for an overman figure to appear would seem to be permissible for one individual, many, or even a social ideal, depending on the culture within which it appears. Modernity, in Nietzsche’s view, is in such a state of decadence that it would be fortunate, indeed, to see the emergence of even one such type, given that modern sociopolitical arrangements are more conducive to creating the egalitarian “last man” who “blinks” at expectations for rank, self-overcoming, and striving for greatness. The last men are “ the most harmful to the species because they preserve their existence as much at the expense of the truth as at the expense of the future” (“Why I am a Destiny” in Ecce Homo 1). Although Nietzsche never lays out a precise political program from these ideas, it is at least clear that theoretical justifications for complacency or passivity are antithetical to his philosophy. What, then, may be said about Nietzsche as political thinker? Nietzsche’s political sympathies are definitely not democratic in any ordinary way of thinking about that sort of arrangement. Nor are they socialist or Marxist.

Nietzsche’s political sympathies have been called “aristocratic,” which is accurate enough only if one does not confuse the term with European royalty, landed gentry, old money or the like and if one keeps in mind the original Greek meaning of the term, “aristos,” which meant “the good man, the man with power.” A certain ambiguity exists, for Nietzsche, in the term “good man.” On the one hand, the modern, egalitarian “good man,” the “last man,” expresses hostility for those types willing to impose measures of rank and who would dare to want greatness and to strive for it. Such hostilities are born out of ressentiment and inherited from Judeo-Christian moral value systems. (Beyond Good and Evil 257-260 and On the Genealogy of Morals essay 1). “Good” in this sense is opposed to “evil,” and the “good man” is the one whose values support the “herd” and whose condemnations are directed at those whose thoughts and actions might disrupt the complacent normalcy of modern life. On the other hand, the kind of “good man” who might overcome the weak pessimism of “herd morality,” the man of strength, a man to confront nihilism, and thus a true benefactor to humanity, would be decidedly “unmodern” and “out of season.” Only such a figure would “keep up the faith in man.” For these reasons, some commentators have found in Nietzsche an existentialist program for the heroic individual dissociated in varying degrees from political considerations. Such readings however ignore or discount Nietzsche’s interest in historical processes and the unavoidable inference that although Nietzsche’s anti-egalitarianism might lead to questionably “unmodern” political conclusions, hierarchy nevertheless implies association.

The distinction between the good man of active power and the other type also points to ambiguity in the concept of freedom. For the hopeless, human freedom is conceived negatively in the “freedom from” restraints, from higher expectations, measures of rank, and the striving for greatness. While the higher type, on the other hand, understands freedom positively in the “freedom for” achievement, for revaluations of values, overcoming nihilism, and self-mastery.

Nietzsche frequently points to such exceptions as they have appeared throughout history—Napoleon is one of his favorite examples. In modernity, the emergence of such figures seems possible only as an isolated event, as a flash of lightening from the dark cloud of humanity. Was there ever a culture, in contrast to modernity, which saw these sorts of higher types emerge in congress as a matter of expectation and design? Nietzsche’s early philological studies on the Greeks, such as Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, The Pre-Platonic Philosophers, “Homer on Competition,” and “The Greek State,” concur that, indeed, the ancient world before Plato produced many exemplary human beings, coming forth independently of each other but “hewn from the same stone,” made possible by the fertile cultural milieu, the social expectation of greatness, and opportunities to prove individual merit in various competitive arenas. Indeed, Greek athletic contests, festivals of music and tragedy, and political life reflected, in Nietzsche’s view, a general appreciation for competition, rank, ingenuity, and the dynamic variation of formal structures of all sorts. Such institutions thereby promoted the elevation of human exemplars. Again, the point must be stressed here that the historical accuracy of Nietzsche’s interpretation of the Greeks is no more relevant to his philosophical schemata than, for example, the actual signing of a material document is to a contractarian political theory. What is important for Nietzsche, throughout his career, is the quick evaluation of social order and heirarchies, made possible for the first time in the nineteenth century by the newly developed “historical sense” (BGE 224) through which Nietzsche draws sweeping conclusions regarding, for example, the characteristics of various moral and religious epochs (BGE 32 and 55), which are themselves pre-conditioned by the material origins of consciousness, from which a pre-human animal acquires the capacity (even the “right”) to make promises and develops into the “sovereign individual” who then bears responsibility for his or her actions and thoughts (GM II.2).

Like these rather ambitious conclusions, Nietzsche’s valorization of the Greeks is partly derived from empirical evidence and partly confected in myth, a methodological concoction that Nietzsche draws from his philological training. If the Greeks, as a different interpretation would have them, bear little resemblance to Nietzsche’s reading, such a difference would have little relevance to Nietzsche’s fundamental thoughts. Later Nietzsche is also clear that his descriptions of the Greeks should not be taken programmatically as a political vision for the future (see for example GS 340).

The “Greeks” are one of Nietzsche’s best exemplars of hope against a meaningless existence, hence his emphasis on the Greek world’s response to the “wisdom of Silenus” in Birth of Tragedy. (ch. 5). If the sovereign individual represents history’s “ripest fruit”, the most recent millennia have created, through rituals of revenge and punishment, a “bad conscience.” The human animal thereby internalizes material forces into feelings of guilt and duty, while externalizing a spirit thus created with hostility towards existence itself (GM II.21). Compared to this typically Christian manner of forming human experiences, the Greeks deified “the animal in man” and thereby kept “bad conscience at bay” (GM II.23).

In addition to exemplifying the Greeks in the early works, Nietzsche lionizes the “artist-genius” and the “sage;” during the middle period he writes confidently, at first, and then longingly about the “scientist,” the “philosopher of the future,” and the “free spirit;” Zarathustra’s decidedly sententious oratory heralds the coming of the Übermensch; the periods in which “revaluation” comes to the fore finds value in the destructive influences of the “madman,” the “immoralist,” the “buffoon,” and even the “criminal.” Finally, Nietzsche’s last works reflect upon his own image, as the “breaker of human history into two,” upon “Mr. Nietzsche,” the “anti-Christian,” the self-anointed clever writer of great books, the creator of Zarathustra, the embodiment of human destiny and humanity’s greatest benefactor: “only after me,” Nietzsche claims in Ecce Homo, “is it possible to hope again” (“Why I am a Destiny” 1). It should be cautioned that important differences exist in the way Nietzsche conceives of each of these various figures, differences that reflect the development of Nietzsche’s philosophical work throughout the periods of his life. For this reason, none of these exemplars should be confused for the others. The bombastic “Mr. Nietzsche” of Ecce Homo is no more the “Übermensch” of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, for example, than the “Zarathustra” character is a “pre-Platonic philosopher” or the alienated, cool, sober, and contemptuous “scientist” is a “tragic artist,” although these figures will frequently share characteristics. Yet, a survey of these exceptions shows that Nietzsche’s philosophy, in his own estimation, needs the apotheosis of a human exemplar, perhaps to keep the search for meaning and redemption from abdicating the earth in metaphysical retreat, perhaps to avert the exhaustion of human creativity, to reawaken the instincts, to inspire the striving for greatness, to remind us that “this has happened once and is therefore a possibility,” or perhaps simply to bestow the “honey offering” of a very useful piece of folly. This need explains the meaning of the parodic fourth book of Zarathustra, which opens with the title character reflecting on the whole of his teachings: “I am he…who once bade himself, and not in vain: ‘Become what you are!’” The subtitle of Nietzsche’s autobiographical Ecce Homo, “How One Becomes What One Is,” strikes a similar chord.

6. Will to Power

The exemplar expresses hope not granted from metaphysical illusions. After sharpening the critique of art and genius during the positivistic period, Nietzsche seems more cautious about heaping praise upon specific historical figures and types, but even when he could no longer find an ideal exception, he nevertheless deemed it requisite to fabricate one in myth. Whereas exceptional humans of the past belong to an exalted “republic of genius,” those of the future, those belonging to human destiny, embody humanity’s highest hopes. As a result of this development, some commentators will emphasize the “philosophy of the future” as one of Nietzsche’s most important ideas. Work pursued in service of the future constitutes for Nietzsche an earthly form of redemption. Yet, exemplars of type, whether in the form of isolated individuals like Napoleon, or of whole cultures like the Greeks, are not caught up in petty historical politics or similar mundane endeavors. According to Nietzsche in Twilight of the Idols, their regenerative powers are necessary for the work of interpreting the meaning and sequence of historical facts.

My Conception of the genius—Great men, like great epochs, are explosive material in whom tremendous energy has been accumulated; their prerequisite has always been, historically and psychologically, that a protracted assembling, accumulating, economizing and preserving has preceded them—that there has been no explosion for a long time. If the tension in the mass has grown too great the merest accidental stimulus suffices to call the “genius,” the “deed,” the great destiny, into the world. Of what account then are circumstances, the epoch, the Zeitgeist, public opinion!…Great human beings are necessary, the epoch in which they appear is accidental… (“Expeditions of an Untimely Man,” 44).

It is with this understanding of the “great man” that Nietzsche, in Ecce Homo, proclaims even himself a great man, “dynamite,”“breaking the history of humanity in two” (“Why I am a Destiny” 1 and 8). A human exemplar, interpreted affirmatively in service of a hopeful future, is a “great event” denoting qualitative differences amidst the play of historical determinations. Thus, it belongs, in this reading, to Nietzsche’s cosmological vision of an indifferent nature marked occasionally by the boundary-stones of noble and sometimes violent uprisings.

To what extent is Nietzsche entitled to such a vision? Unlike nihilism, pessimism, and the death of God, which are historically, scientifically, and sometimes logically derived, Nietzsche’s “yes-saying” concepts seem to be derived from intuition, although Nietzsche will frequently support even these great hopes with bits of inductive reasoning. Nietzsche attempts to describe the logical structure of great events, as if a critical understanding of them pertains to their recurrence in modernity: great men have a “historical and psychological prerequisite.” Historically, there must be a time of waiting and gathering energy, as we find, for example, in the opening scene of Zarathustra. The great man and the great deed belong to a human destiny, one that emerges in situations of crisis and severe want. Psychologically, they are the effects of human energy stored and kept dormant for long periods of time in dark clouds of indifference. Primal energy gathers to a point before a cataclysmic event, like a chemical reaction with an electrical charge, unleashes some decisive, episodic force on all humanity. From here, the logic unfolds categorically: all great events, having occurred, are possibilities. All possibilities become necessities, given an infinite amount of time. Perhaps understanding this logic marks a qualitative difference in the way existence is understood. Perhaps this qualitative difference will spark the revaluation of values. When a momentous event takes place, the exception bolts from the cloud of normalcy as a point of extreme difference. In such ways, using this difference as a reference, as a “boundary-stone” on the river of eternal becoming, the meaning of the past is once again determined and the course of the future is set for a while, at least until a coming epoch unleashes the next great transvaluative event. Conditions for the occurrence of such events, and for the event of grasping this logic itself, are conceptualized, cosmologically in this reading, under the appellation “will to power.”

Before developing this reading further, it should be noted some commentators argue that the cosmological interpretation of will to power makes too strong a claim and that the extent of will to power’s domain ought to be limited to what the idea might explain as a theory of moral psychology, as the principle of an anthropology regarding the natural history of morals, or as a response to evolutionary theories placed in the service of utility. Such commentators will maintain that Nietzsche either in no way intends to construct a new meta-theory, or if he does then such intentions are mistaken and in conflict with his more prescient insights. Indeed, much evidence exists to support each of these positions. As an enthusiastic reader of the French Moralists of the eighteenth century, Nietzsche held the view that all human actions are motivated by the desire “to increase the feeling of power” (GS 13). This view seems to make Nietzsche’s insights regarding moral psychology akin to psychological egoism and would thus make doubtful the popular notion that Nietzsche advocated something like an egoistic ethic. Nevertheless, with this bit of moral psychology, a debate exists among commentators concerning whether Nietzsche intends to make dubious morality per se or whether he merely endeavors to expose those life-denying ways of moralizing inherited from the beginning of Western thought. Nietzsche, at the very least, is not concerned with divining origins. He is interested, rather, in measuring the value of what is taken as true, if such a thing can be measured. For Nietzsche, a long, murky, and thereby misunderstood history has conditioned the human animal in response to physical, psychological, and social necessities (GM II) and in ways that have created additional needs, including primarily the need to believe in a purpose for its very existence (GS 1). This ultimate need may be uncritically engaged, as happens with the incomplete nihilism of those who wish to remain in the shadow of metaphysics and with the laisser aller of the last man who overcomes dogmatism by making humanity impotent (BGE 188). On the other hand, a critical engagement with history is attempted in Nietzsche’s genealogies, which may enlighten the historical consciousness with a sort of transparency regarding the drive for truth and its consequences for determining the human condition. In the more critical engagement, Nietzsche attempts to transform the need for truth and reconstitute the truth drive in ways that are already incredulous towards the dogmatizing tendency of philosophy and thus able to withstand the new suspicions (BGE 22 and 34). Thus, the philosophical exemplar of the future stands in contrast, once again, to the uncritical man of the nineteenth century whose hidden metaphysical principles of utility and comfort fail to complete the overcoming of nihilism (Ecce Homo, “Why I am a Destiny” 4). The question of whether Nietzsche’s transformation of physical and psychological need with a doctrine of the will to power, in making an affirmative principle out of one that has dissolved the highest principles hitherto, simply replaces one metaphysical doctrine with another, or even expresses completely all that has been implicit in metaphysics per se since its inception continues to draw the interest of Nietzsche commentators today. Perhaps the radicalization of will to power in this way amounts to no more than an account of this world to the exclusion of any other. At any rate, the exemplary type, the philosophy of the future, and will to power comprise aspects of Nietzsche’s affirmative thinking. When the egoist’s “I will” becomes transparent to itself a new beginning is thereby made possible. Nietzsche thus attempts to bring forward precisely that kind of affirmation which exists in and through its own essence, insofar as will to power as a principle of affirmation is made possible by its own destructive modalities which pulls back the curtain on metaphysical illusions and dogma founded on them.

The historical situation that conditions Nietzsche’s will to power involves not only the death of God and the reappearance of pessimism, but also the nineteenth century’s increased historical awareness, and with it the return of the ancient philosophical problem of emergence. How does the exceptional, for example, begin to take shape in the ordinary, or truth in untruth, reason in un-reason, social order and law in violence, a being in becoming? The variation and formal emergence of each of these states must, according to Nietzsche, be understood as a possibility only within a presumed sphere of associated events. One could thus also speak of the “emergence,” as part of this sphere, of a given form’s disintegration. Indeed, the new cosmology must account for such a fate. Most importantly, the new cosmology must grant meaning to this eternal recurrence of emergence and disintegration without, however, taking vengeance upon it. This is to say that in the teaching of such a worldview, the “innocence of becoming” must be restored. The problem of emergence attracted Nietzsche’s interest in the earliest writings, but he apparently began to conceptualize it in published texts during the middle period, when his work freed itself from the early period’s “metaphysics of aesthetics.” The opening passage from 1878’s Human, All Too Human gives some indication of how Nietzsche’s thinking on this ancient problem begins to take shape:

Chemistry of concepts and feelings. In almost all respects, philosophical problems today are again formulated as they were two thousand years ago: how can something arise from its opposite….? Until now, metaphysical philosophy has overcome this difficulty by denying the origin of the one from the other, and by assuming for the more highly valued things some miraculous origin…. Historical philosophy, on the other hand, the very youngest of all philosophical methods, which can no longer be even conceived of as separate from the natural sciences, has determined in isolated cases (and will probably conclude in all of them) that they are not opposites, only exaggerated to be so by the metaphysical view….As historical philosophy explains it, there exists, strictly considered, neither a selfless act nor a completely disinterested observation: both are merely sublimations. In them the basic element appears to be virtually dispersed and proves to be present only to the most careful observer. (Human, All Too Human, 1)

It is telling that Human begins by alluding to the problem of “emergence” as it is brought to light again by the “historical philosophical method.” A decidedly un-scientific “metaphysical view,” by comparison, looks rather for miraculous origins in support of the highest values. Next, in an unexpected move, Nietzsche relates the general problem of emergence to two specific issues, one concerning morals (“selfless acts”) and the other, knowledge—which is taken to include judgment (“disinterested observations”): “in them the basic element appears to be virtually dispersed” and discernable “only to the most careful observer.”

The logical structure of emergence, here, appears to have been borrowed from Hegel and, to be sure, one could point to many Hegelian traces in Nietzsche’s thought. But previously in 1874’s “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life,” from Untimely Meditations, Nietzsche had steadfastly refuted the dialectical logic of a “world historical process,” the Absolute Idea, and cunning reason. What, then, is “the basic element”, dispersed in morals and knowledge? How is it dispersed so that only the careful observer can detect it? The most decisive moment in Nietzsche’s development of a cosmology seems to have occurred when Nietzsche plumbed the surface of his early studies on the pathos and social construction of truth to discover a more prevalent feeling, one animating all socially relevant acts. In Book One of the The Gay Science (certainly one of the greatest works in whole corpus) Nietzsche, in the role of “careful observer,” identifies, with a bit of moral psychology, the one motive spurring all such acts:

On the doctrine of the feeling of power. Benefiting and hurting others are ways of exercising one’s power upon others: that is all one desires in such cases…. Whether benefiting or hurting others involves sacrifices for us does not affect the ultimate value of our actions. Even if we offer our lives, as martyrs do for their church, this is a sacrifice that is offered for our desire for power or for the purpose of preserving our feeling of power. Those who feel “I possess Truth”—how many possessions would they not abandon in order to save this feeling!…Certainly the state in which we hurt others is rarely as agreeable, in an unadulterated way, as that in which we benefit others; it is a sign that we are still lacking power, or it shows a sense of frustration in the face of this poverty….(aphorism 13).

The “ultimate value” of our actions, even concerning those intended to pursue or preserve “truth,” are not measured by the goodness we bring others, notwithstanding the fact that intentionally harmful acts will be indicative of a desperate want of power. Nietzsche, here, asserts the significance of enhancing the feeling of power, and with this aphorism from 1882 we are on the way to seeing how “the feeling of power” will replace, for Nietzsche, otherworldly measures of value, as we read in finalized form in the second aphorism of 1888’s The Anti-Christ:

What is good?—All that heightens the feeling of power, the will to power, power itself in man. What is bad?—All that proceeds from weakness. What is happiness?—The feeling that power increases—that a resistance is overcome.

No otherworldly measures exist, for Nietzsche. Yet, one should not conclude from this absence of a transcendental measure that all expressions of power are qualitatively the same. Certainly, the possession of a Machiavellian virtù will find many natural advantages in this world, but Nietzsche locates the most important aspect of “overcoming resistance” in self-mastery and self-commanding. In Zarathustra’s chapter, “Of Self-Overcoming,” all living creatures are said to be obeying something, while “he who cannot obey himself will be commanded. That is the nature of living creatures.” It is important to note the disjunction: one may obey oneself or one may not. Either way, one will be commanded, but the difference is qualitative. Moreover, “commanding is more difficult than obeying” (BGE 188 repeats this theme). Hence, one will take the easier path, if unable to command, choosing instead to obey the directions of another. The exception, however, will command and obey the healthy and self-mastering demands of a willing self. But why, we might ask, are all living things beholden to such commanding and obeying? Where is the proof of necessity here? Zarathustra answers:

Listen to my teaching, you wisest men! Test in earnest whether I have crept into the heart of life itself and down to the roots of its heart! Where I found a living creature, there I found will to power; and even in the will of the servant, I found the will to be master (Z “Of the Self-Overcoming”).

Here, apparently, Nietzsche’s doctrine of the feeling of power has become more than an observation on the natural history and psychology of morals. The “teaching” reaches into the heart of life, and it says something absolute about obeying and commanding. But what is being obeyed, on the cosmological level, and what is being commanded? At this point, Zarathustra passes on a secret told to him by life itself: “behold [life says], I am that which must overcome itself again and again…And you too, enlightened man, are only a path and a footstep of my will: truly, my will to power walks with the feet of your will to truth.” We see here that a principle, will to power, is embodied by the human being’s will to truth, and we may imagine it taking other forms as well. Reflecting on this insight, for example, Zarathustra claims to have solved “the riddle of the hearts” of the creator of values: “you exert power with your values and doctrines of good and evil, you assessors of values….but a mightier power and a new overcoming grow from out of your values…” That mightier power growing in and through the embodiment and expression of human values is will to power.

It is important not to disassociate will to power, as a cosmology, from the human being’s drive to create values. To be sure, Nietzsche is still saying that the creation of values expresses a desire for power, and the first essay of 1887’s On the Genealogy of Morality returns to this simple formula. Here, Nietzsche appropriates a well-known element of Hegel’s Phenomenology, the structural movement of thought between basic types called “masters and slaves.” This appropriation has the affect of emphasizing the difference between Nietzsche’s own historical “genealogies” and that of Hegel’s “dialectic” (as is worked out in Deleuze’s study of Nietzsche). Master and slave moralities, the truths of which are confirmed independently by feelings that power has been increased, are expressions of the human being’s will to power in qualitatively different states of health. The former is a consequence of strength, cheerful optimism and naiveté, while the latter stems from impotency, pessimism, cunning and, most famously, ressentiment, the creative reaction of a “bad conscience” coming to form as it turns against itself in hatred. The venom of slave morality is thus directed outwardly in ressentiment and inwardly in bad conscience. Differing concepts of “good,” moreover, belong to master and slave value systems. Master morality complements its good with the designation, “bad,” understood to be associated with the one who is inferior, weak, and cowardly. For slave morality, on the other hand, the designation, “good” is itself the complement of “evil,” the primary understanding of value in this scheme, associated with the one possessing superior strength. Thus, the “good man” in the unalloyed form of “master morality” will be the “evil man,” the man against whom ressentiment is directed, in the purest form of “slave morality.” Nietzsche is careful to add, at least in Beyond Good and Evil, that all modern value systems are constituted by compounding, in varying degrees, these two basic elements. Only a “genealogical” study of how these modern systems came to form will uncover the qualitative strengths and weaknesses of any normative judgment.

The language and method of The Genealogy hearken back to The Gay Science’s “doctrine of the feeling of power.” But, as we have seen, in the period between 1882 and 1887, and from out of the psychological-historical description of morality, truth, and the feeling of power, Nietzsche has given agency to the willing as such that lives in and through the embrace of power, and he generalizes the willing agent in order to include “life” and “the world” and the principle therein by which entities emerge embodied. The ancient philosophical problem of emergence is resolved, in part, with the cosmology of a creative, self-grounding, self-generating, sustaining and enhancing will to power. Such willing, most importantly, commands, which at the same time is an obeying: difference emerges from out of indifference and overcomes it, at least for a while. Life, in this view, is essentially self-overcoming, a self-empowering power accomplishing more power to no other end. In a notebook entry from 1885, Will to Power’s aphorism 1067, Nietzsche’s cosmological intuitions take flight:

And do you know what “the world” is to me? Shall I show it to you in my mirror? This world: a monster of energy, without beginning, without end…as force throughout, as a play of forces and waves of forces…a sea of forces flowing and rushing together, eternally changing and eternally flooding back with tremendous years of recurrence…out of the play of contradictions back to the joy of concord, still blessing itself as that which must return eternally, as a becoming that knows no satiety, no disgust, no weariness; this my Dionysian world of the eternally self-creating, the eternally self-destroying, this mystery world of the two-fold voluptuous delight, my “beyond good and evil,” without goal, unless the joy of the circle is itself a goal….This world is the will to power—and nothing besides! And you yourselves are also this will to power—and nothing besides!

Nietzsche discovers, here, the words to articulate one of his most ambitious concepts. The will to power is now described in terms of eternal and world-encompassing creativity and destructiveness, thought over the expanse of “tremendous years” and in terms of “recurrence,” what Foucault has described as the “play of domination” (1971). In some respects Nietzsche has indeed rediscovered the temporal structure of Heraclitus’ child at play, arranging toys in fanciful constructions of what merely seems like everything great and noble, before tearing down this structure and building again on the precipice of a new mishap. To live in this manner, according to Nietzsche in The Gay Science, to affirm this kind of cosmology and its form of eternity, is to “live dangerously” and to “love fate” (amor fati).