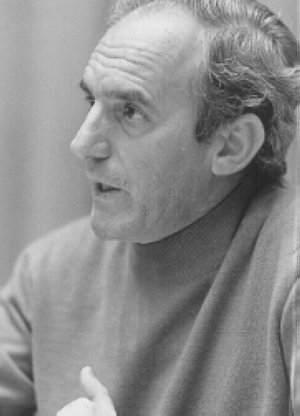

Ignacio Ellacuría (1930—1989)

Ignacio Ellacuría, a naturalized citizen of El Salvador, was born in Spain in 1930. He joined the Jesuits in 1947 and was quickly sent to El Salvador, where he lived and worked for the next forty-two years, except for periods when he was pursuing his education in Ecuador, Spain, and West Germany. He developed an important and novel contribution to Latin American Liberation Philosophy. The body of thought known as Liberation Philosophy developed in Latin America in the second half of the Twentieth Century. It grew out of the works of philosophers working in Peru (A. Salazar Bondy) and Mexico (Leopoldo Zea), and quickly spread throughout Latin America. It resulted from efforts by these philosophers to create a Latin American philosophy by looking at how the discipline could help to make sense of Latin American reality. That reality, as distinct from the European (and later North American) context in which the modern Western philosophical tradition developed, is one of dependence on economic and political (and to some extent cultural) factors that are beyond one’s control. In thematizing dependency, Latin American philosophy developed a liberation philosophy that focused on the social and personal imperative to overcome dependency as the path toward the fullness of one’s humanity, given the conditions of dependency. There are at least five different schools within Latin American liberation philosophy (see Cerutti in the Bibliography below), but all are grounded in the attempt to use philosophy to understand the Latin American reality of dependency and the need to overcome it.

Ignacio Ellacuría, a naturalized citizen of El Salvador, was born in Spain in 1930. He joined the Jesuits in 1947 and was quickly sent to El Salvador, where he lived and worked for the next forty-two years, except for periods when he was pursuing his education in Ecuador, Spain, and West Germany. He developed an important and novel contribution to Latin American Liberation Philosophy. The body of thought known as Liberation Philosophy developed in Latin America in the second half of the Twentieth Century. It grew out of the works of philosophers working in Peru (A. Salazar Bondy) and Mexico (Leopoldo Zea), and quickly spread throughout Latin America. It resulted from efforts by these philosophers to create a Latin American philosophy by looking at how the discipline could help to make sense of Latin American reality. That reality, as distinct from the European (and later North American) context in which the modern Western philosophical tradition developed, is one of dependence on economic and political (and to some extent cultural) factors that are beyond one’s control. In thematizing dependency, Latin American philosophy developed a liberation philosophy that focused on the social and personal imperative to overcome dependency as the path toward the fullness of one’s humanity, given the conditions of dependency. There are at least five different schools within Latin American liberation philosophy (see Cerutti in the Bibliography below), but all are grounded in the attempt to use philosophy to understand the Latin American reality of dependency and the need to overcome it.

Table of Contents

1. Life

Ellacuría’s initial training in philosophy was in the Neo-Scholasticism required at that time of all Jesuits. Later he studied Ortega, Bergson, Heidegger, phenomenology, and the existentialists. All of these influenced him, but the key influences in the make up of his mature philosophical thought were Hegel, Marx, and the Basque philosopher Xavier Zubiri (1898-1983). Ellacuría worked on his doctorate under Zubiri from 1962 to 1965, writing a dissertation that reached some 1100 pages on the concept of essence in Zubiri’s thought. He also studied theology with the great Heideggerian Jesuit, Karl Rahner, and had finished all the requirements for a second PhD, but did not write the dissertation (which he was also going to write under Zubiri). For the next 18 years, until Zubiri’s death in 1983, they were close collaborators, with Ellacuría returning to Spain from El Salvador for a few months each year to facilitate their work. The two worked together on most of Zubiri’s texts and talks, eventually reaching the point where Zubiri would not publish something, or even present a lecture, without first showing the material to Ellacuría.

Zubiri is a major figure in 20th century Spanish philosophy and has had a lot of influence in Latin America, largely through the efforts of Ellacuría, but his work is not well known in the countries more traditionally associated with Continental Philosophy (France and Germany) or in the Anglo-American tradition. By the age of 23, Zubiri had finished both a PhD in theology at the Gregorian University and a PhD in philosophy at the University of Madrid. At 28 he was named to the prestigious chair in the history of philosophy at the University of Madrid, and for the next few years he traveled widely in Europe to study with experts in many different fields: philosophy with Husserl and Heidegger, physics with Schrödinger and De Broglie, as well as biology and mathematics with luminaries of the day. Zubiri also taught in Paris at the Institut Catholique and at the University of Barcelona, but in 1942 he left formal academia and for the rest of his life conducted seminars on his own.

From among a large number of very important publications, his two most important are On Essence (1963) and the three-volume work, Sentient Intelligence (1980-83). Ellacuría, who knew all of Zubiri’s work, was particularly familiar with these two works: his doctoral dissertation was on the former, and he worked very closely with Zubiri to bring the latter to publication before Zubiri’s death.

Zubiri created a systematic philosophy grounded in a re-configuring and overcoming of the distinction between epistemology and metaphysics, between the knower and the known (for more, see the section below on Ellacuría’s philosophy). There are now various interpretations of Zubiri’s work (among others, phenomenological, Nietzschean, praxical) with Ellacuría heading up the historical/metaphysical interpretation. Although there is no agreement among Zubirian scholars as to which among these is the better interpretation, the fact that Zubiri adopted Ellacuría as his closest collaborator for the last 20 years of his life has to lend some weight to Ellacuría’s interpretation

Ellacuría was murdered in 1989 – along with five other Jesuits with whom he lived, their housekeeper and her daughter – at the hands of an elite, US-trained squadron of the Salvadoran army. The murders came towards the end of El Salvador’s long civil war (1980-1992) between a right-wing government and leftist guerillas. At the time of his death, Ellacuría was president of the country’s prestigious Jesuit university, the University of Central America (UCA), as well as chair of its philosophy department and editor of many of its scholarly publications. In his quarter century with the UCA, the last ten years as its president, he had played a principle role in molding it into a university whose full institutional power – that is, through its research, teaching and publications – was directed towards uncovering the causes of poverty and oppression in El Salvador. In addition, he spoke out frequently on these topics as a regular contributor to the country’s newspapers, radio and television programs. He also addressed these topics frequently in his scholarly publications on philosophy and theology. These were the reasons behind his murder.

During his lifetime Ellacuría was known, primarily, as one of the principle contributors to Latin American liberation theology. However, he also spent the last two decades of his life elaborating a liberation philosophy. The latter work was left, at the time of his murder, unfinished, unpublished, and scattered across many different writings. In the years since his death, a number of scholars have pieced together his philosophical thought, and it is now possible to argue that Ellacuría had a well-developed philosophy that represents an important contribution to Latin American liberation philosophy.

2. Ellacuría’s Philosophy of Liberation

Ellacuría argued that philosophy, in order to remain true to itself, must be a philosophy of liberation. He begins with the assertion that it is the responsibility of philosophy to help us in figuring out what reality is and in situating ourselves within reality. For Ellacuría, human reality is historical and social: the range of possibilities in which the freedom of any given individual’s life must be exercised is the result of both past human actions and the society in which the individual lives. Human actions accrete as history, and within this reality individuals and societies are able to realize some of the possibilities handed over by the past, in the process creating new possibilities to hand over to future generations. There is progress in reality, from the physical to the biological to the praxical, each of these representing a further unfolding of an ever more complex reality. In the realm of praxis (his word for human action to change reality), human beings act to realize a wider range of possibility: praxis seeks to realize a fuller praxis. Thus, praxis realizes a gradual increase in liberty: praxis gradually liberates liberty.

Human beings, as praxical beings, are responsible for the further unfolding of reality, i.e., for the realization of a reality in which all praxical beings can fully realize themselves as such. Ellacuría argues that the vantage point from which one can see most clearly what reality unfolding as history has and has not delivered, is the perspective of the marginalized. Thus, the philosophy of history must make a preferential option for the marginalized, i.e., it must be a philosophy of liberation.

Ellacuría’s liberation philosophy begins with a critique grounded in a Zubirian metaphysics that is radically critical of all forms of idealism, including most of what has passed for realism in the history of Western philosophy. This critique argues that the Western tradition made a fundamental error, from Parmenides on, in separating sensation and the intellect, an error which distorted all subsequent philosophy. This error resulted in the “logification of intelligence” and the “entification of reality.” By the former, Zubiri means that the full powers of the intellect have been reduced to a predicative logos, i.e., a logos whose function is to determine what things are, in themselves and in relation to other things. Zubiri argues that while this is a vital part of intelligence, it is not the only part and not the most fundamental part, but Western philosophy reduced intelligence to this predicative logos. In doing so, the object of logos, i.e., the being of entities, became the sum total of reality: reality became entified. These two distortions (the logification of intelligence and entification of reality) can only be overcome by the recognition that sensation and intellection are not separate, that they are two aspects of a single faculty. Zubiri called this faculty the sentient intellect. By this term he meant that, for human beings, the intellect is always sentient and sensation is always intelligent. The two faculties of sensation and intelligence are, for human beings, one and the same faculty. This new, human faculty, the “sentient intellect,” is Zubiri’s candidate for the specific difference of human beings as a species: a new type of sensation that is essentially different from the sense faculty of other animals, different by the addition of intelligence.

In what way is human sensation essentially different than the sensation of other animals? For Zubiri, part of every human sensation, but absent in animal sensation, is the awareness that the object sensed is real, i.e., that it is has the property of being something in and of itself, independent from me, that it is not a willful extension of me. This recognition of the real as real is the fundamental act of the intelligence; it is the intellectual act that is part and parcel, structurally, inextricably, of every act of human sensation. Thus, through the unitary faculty of the sentient intellect we apprehend reality as real. The consequence of this is that we are always already installed in reality. There is no question about how the mind reaches what is real, no need to build a bridge between the mind and reality.

The intellect, like the rest of the body, evolved as a response to challenges posed by the environment. Animals respond to stimuli while humans are confronted with possible realities. Animals are faced with a predetermined cast of responses to a given stimuli. But human beings in any given situation have an open spectrum of options from among which we must choose. We are, in effect, faced with the possibilities of many different realities, and our choices contribute to the determination of reality as it is realized; thus the name that Zubiri gives to human beings: the “reality animal.” The openness of the options facing us is the structural basis of our freedom. Freedom is not something mysterious but a result of the evolutionary pressures that lead to the emergence of a sentient intelligence. The evolutionary niche occupied by human beings is one in which the cast of responses to a stimulus grew to the point where there was no longer anything automatic about which possible response would be enacted. Our niche is the one where the huge number of possible responses opened up different potential realities, allowing us more fully to exploit reality’s possibilities. In other words, our niche is precisely the freedom to choose from among the huge number of possible responses, i.e., from among the huge number of possible realities. To manage this operation of choosing, animal sensation evolved into the sentient intellect.

So, according to Zubirian metaphysics, human beings are always already installed in reality as the part of reality whose actions determine future reality: humans are the part of reality that now unfolds further reality. In previous eras, the unfolding of reality took place by physical and biological forces, but now it is human forces (praxis) that unfolds reality. This is not to say that physical and biological forces are no longer present. They are present, and continue to form the foundation of praxis, but praxis outstrips them. An authentic praxis, however, must recognize its foundation in biology and physics – that is why the physical and biological needs of human beings must be met in order for the fullness of human praxis to be realizable. Thus, an authentic praxis must strive for a reality in which the physical and biological needs of all humans are met.

Ellacuría concludes from all of this that the primary question facing human beings – metaphysical and ethical at once – is: given that we are always already in reality, what is the proper way to engage it? Ellacuría characterizes Zubiri’s intellectual motto as “to come as close as possible, intellectually, to the reality of things.” Western philosophy “had not found an adequate way to shoulder responsibility for reality [hacerse cargo de la realidad].” The search for the right way to engage reality was the motivation for Ellacuría’s work. For Ellacuría, humans are now shouldered with responsibility for reality in the sense of being charged with the task of figuring out what is the proper way of exercising the fundamental freedom opened up by the advent, within evolution, of the sentient intellect. In this sense, human beings are the responsible part of reality, i.e., the part of reality whose task it is to figure out how to respond to reality thereby creating a new reality unfolded out of the previous reality. In order for humans to properly exercise this responsibility, we must discern the direction in which reality needs to be taken.

The sentient intellect evolved to enable us to act more effectively in insuring our own survival. This is not selfish, as it may at first sound, given the element of responsibility that comes along with the sentient intellect. As the reality animal, our actions decide between various possible future realities. Thus, as the responsible part of reality, we are now charged with assisting in the further realization of reality. Ellacuría gives the special name of “praxis” to this action that determines reality.

If we look at the development of reality, we can discern a progression from matter, to life, to human life. This progression has been under the control of, first, physical forces, then biological forces, and now, with the evolution of the being with sentient intelligence, the progressive unfolding of reality is subject to the force of praxis. Thus there is a gradual liberation of more developed forces. Subsequent forces do not erase the earlier ones, but rather subsume them dialectically. Thus, human praxis cannot ignore the physical and biological needs of reality: these are the imperatives that must be satisfied on the way to the full realization of praxis itself. Reality has delivered, liberated, successively more developed forces, each layered over the previous: the biological on top of the physical, and the praxical on top of the biological. The direction of this process can be seen: praxis is the most advanced force reality has developed, and praxis must now take its place as the force that most drives the further unfolding of reality (just as physical and biological forces had, successively, taken that place previously). Since the essence of praxis is freedom, human beings must now exercise our freedom such that we further the proper development of reality. To remain true to our essence, and true to the essence of reality, we must act so as to further the development, the spread, of praxis. Thus, the direction of this process of liberation is the liberation of liberty itself, a process for which the reality animal, the praxical being, is responsible. Thus the full realization of reality entails this: praxical beings acting to bring about the realization of the reality in which all praxical beings (that is, all human beings) can realize the fullness of their praxical essence. In other words, physical and biological forces brought about human beings; but the nature of human beings is such that we are now responsible for the further and fuller realization of reality, which realization is precisely the liberation of all human beings such that they can realize the fullness of their essence. Thus Ellacuría is able to argue that the metaphysics of reality demands a liberatory praxis from us: liberation, because of the essence of human beings and the nature of reality, is a metaphysical imperative.

We can begin to see the prescriptions that emerge from the foregoing analysis. Ellacuría’s liberation philosophy allows him to argue that the essence of being human demands that society be structured in such a way as to meet the physical and biological needs of human beings at an adequate level, i.e., a level that frees us to pursue our essence as praxical beings. Further, his analysis suggests that it is the duty of those of us who enjoy a wider exercise of freedom to dedicate our talents and efforts towards the construction of such a society: our essence as the leading edge of reality that is now responsible for the further unfolding of reality demands that we assist in the establishment of a reality in which praxis is more fully realized, i.e., a reality in which more people (ultimately, all people) are freed from basic wants (inflicted on them by poverty) so that they can exercise their praxis. In other words, the full self-realization of the privileged lies in their enlisting themselves in the struggles of the oppressed. This does not mean that the privileged have to become oppressed. Rather, it means that they should use the education and power delivered to them by their socially and historically conditioned privilege to further the struggles of the oppressed. Note that this is not paternalistic. The struggles of the oppressed represent the leading edge of reality’s further development. The endeavors of the privileged apart from these struggles represent dead-end dilly-dallying (no matter how important they seem to those engaged in them) that does not further the humanization of reality and, thus, will not become an enduring part of human history. Far from paternalism, what saves the privileged from the meaningless pursuits with which they are wont to fill their time, and thus from a meaningless life, is the decision to lend their efforts to further the cause of the oppressed.

Thus, with Zubirian realism and in creative dialogue with Marx, Ellacuría undertook, from the perspective of the poor of the Third World, the project of forging a philosophy that recognized the material nature of being human – and thus the need to take into account the structures of poverty and oppression – while holding open the possibility of a transcendent realm, a realm one and the same with the material realm (actually part of the material realm) in which can exist human freedom and perhaps even God. Ellacuría was constructing a liberation philosophy in the service of the concrete needs of the Latin American people and of the Third World in general. It is a project in the service of which Ellacuría took great strides, but which remained unfinished at his death.

3. References and Further Reading

There still remain a number of unpublished pieces that are important to Ellacuría’s liberation philosophy. These consist primarily of extensive notes he took for the courses he taught at the UCA. These, and all of Ellacuría’s published and unpublished writings, are located in the Ignacio Ellacuría Archives at the Universidad Centroamericana (UCA) in San Salvador, El Salvador.

- Burke, Kevin (2000). The Ground Beneath the Cross: The Theology of Ignacio Ellacuría, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- In English, this book contains good chapters (chs. 2-4) on the philosophical foundation of Ellacuría’s theological thought.

- Cerutti, Horacio (1992). La Filosofia de la Liberación Latinoamericana, Mexico City: FCE.

- The best overview of Latin American liberation philosophy, though the book was written before Ellacuría’s contributions to the topic were widely known. Thus, Cerutti charts four main currents of Latin American liberation philosophy. Ellacuría’s contributions represent a fifth current.

- Ellacuría, Ignacio (2000-2002). Escritos Teológicos [ET], four volumes, San Salvador: UCA Editores.

- Some philosophically important pieces are also collected here.

- Ellacuría, Ignacio (1996-2001). Escritos Filosóficos [EF], three volumes, San Salvador: UCA Editores.

- His scores of important philosophical essays have been collected here.

- Ellacuría, Ignacio (1999). Escritos Universitarios [EU], San Salvador: UCA Editores.

- Some philosophically important pieces are also collected here.

- Ellacuría, Ignacio (1993). Veinte Años de Historia en El Salvador: Escritos Políticos [VA], three volumes, second edition, San Salvador: UCA Editores.

- Some philosophically important pieces are also collected here.

- Ellacuría, Ignacio (1990). Filosofía de la Realidad Histórica, San Salvador: UCA Editores.

- Ellacuría’s main philosophical work. This 600-page book was written and revised a couple of times in the early 1970s. It was never finished (there are indications in his notes that he intended to write more chapters) but it is fairly polished and the best indication of the scope and force of his argument for liberation philosophy.

- Hassett, John & Hugh Lacey, eds. (1991). Towards a Society that Serves Its People: The Intellectual Contribution of El Salvador’s Murdered Jesuits [TSSP], Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- English translations of eight of his essays (philosophical, theological and political).

- Samour, Héctor (2002). Voluntad de Liberación: El Pensamiento Filosófico de Ignacio Ellacuría, San Salvador: UCA Editores.

- The most thorough presentation of Ellacuría’s philosophical thought. Samour is the scholar who has done the most to pull together, from the thousands of pages of unpublished and published material, Ellacuría’s liberation philosophy and this comprehensive book is the result of his labors.

- Whitfield, Teresa (1995). Paying the Price: Ignacio Ellacuría and the Murdered Jesuits of El Salvador, Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- The best intellectual biography on Ellacuría.

From among all of the collected essays, the most important for understanding Ellacuría’s liberation philosophy are the following:

- “Filosofía y Política” [1972], VA-1, pp. 47-62.

- “Liberación: Misión y Carisma de la Iglesia” [1973], ET-2, pp. 553-584.

- “Diez Años Después: ¿Es Posible una Universidad Distinta?” [1975], EU, pp. 49-92 (an English translation is available in TSSP, pp. 177-207).

- “Hacia una Fundamentación del Método Teológico Latinoamericana” [1975], ET-1, pp. 187-218.

- “Filosofía, ¿Para Qué?” [1976], EF-3, pp. 115-132.

- “Fundamentación Biológica de la Ética” [1979], EF-3, pp, 251-269.

- “Universidad y Política” [1980], VA-1, pp. 17-46.

- “El Objeto de la Filosofía” [1981], VA-1, pp. 63-92.

- “Función Liberadora de la Filosofía” [1985], VA-1, pp. 93-122.

- “La Superación del Reduccionismo Idealista en Zubiri” [1988], EF-3, pp. 403-430.

- “El Desafío de las Mayorías Populares” (1989), EU, pp. 297-306 (an English translation is available in TSSP, pp. 171-176).

- “En Torno al Concepto y a la Idea de Liberación” [1989], ET-1, pp. 629-657.

- “Utopía y Profetismo en América Latina” [1989], ET-2, pp. 233-294 (an English translation is available in TSSP, pp. 44-88).

Author Information

David I. Gandolfo

Email: david.gandolfo@furman.edu

Furman University

U. S. A.