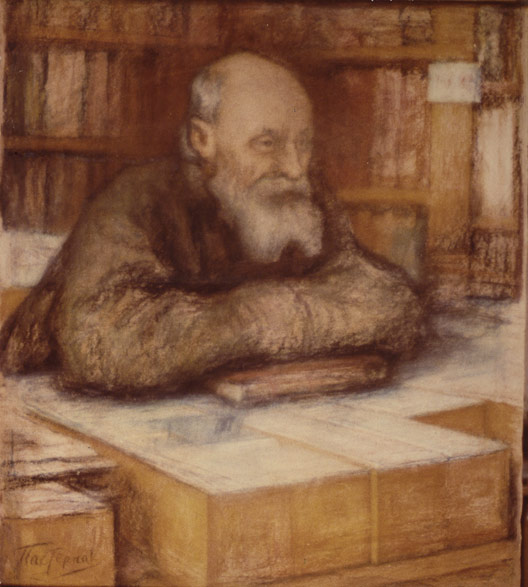

Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov (1829—1903)

Fedorov’s thoughts have been variously described as bold, culminating, curious, easily-misunderstood, extreme, hazy, idealist, naive, of-value, scientifico-magical, special, unexpected, unique, and utopian. Many of the small number of philosophers familiar with Fedorov admit his originality, his independence, his human concern, perhaps even his logic — up to a point. But his resurrection project is viewed with understandable skepticism and often dismissed as an impossible fantasy. Interestingly, the harshest criticism has come from Christian thinkers such as Florovsky and Ustryalov whose objections bear religious overtones; some materialists such as Muravyov and Setnitsky have been quite benign and favorable by comparison. Perhaps all would agree, however, on Fedorov’s single-mindedness. Looked at positively, this is simply another term for purity-of-heart, a quality of saintliness. With his strong emphasis on kinship and brotherhood demanding, ultimately, a world in which all must mutually benefit, Fedorov perhaps anticipates Rawls who says: “Thus what we are doing is to combine into one conception the totality of conditions that we are ready upon due reflection to recognize as reasonable in our conduct with regard to one another. … all persons … even … persons who are not contemporaries but who belong to many generations. Thus to see our place in society from the perspective of this position is … to regard the human situation not only from all social but also from all temporal points of view. The perspective of eternity is not a perspective from a certain place beyond the world, nor the point of view of a transcendent being; rather it is a certain form of thought and feeling that rational persons can adopt within the world. … Purity of heart, if one could attain it, would be to see clearly and to act with grace and self-command from this point of view.” Fedorov wrote: “By refusing to grant ourselves the right to set ourselves apart … we are kept from setting any goal for ourselves that is not the common task of all.” But Fedorov’s thought soars beyond the present world to a world of its own, in his insistence that we can become immortal and godlike through rational efforts, and that our moral obligation is to create a heaven to be shared by all who ever lived.

Fedorov’s thoughts have been variously described as bold, culminating, curious, easily-misunderstood, extreme, hazy, idealist, naive, of-value, scientifico-magical, special, unexpected, unique, and utopian. Many of the small number of philosophers familiar with Fedorov admit his originality, his independence, his human concern, perhaps even his logic — up to a point. But his resurrection project is viewed with understandable skepticism and often dismissed as an impossible fantasy. Interestingly, the harshest criticism has come from Christian thinkers such as Florovsky and Ustryalov whose objections bear religious overtones; some materialists such as Muravyov and Setnitsky have been quite benign and favorable by comparison. Perhaps all would agree, however, on Fedorov’s single-mindedness. Looked at positively, this is simply another term for purity-of-heart, a quality of saintliness. With his strong emphasis on kinship and brotherhood demanding, ultimately, a world in which all must mutually benefit, Fedorov perhaps anticipates Rawls who says: “Thus what we are doing is to combine into one conception the totality of conditions that we are ready upon due reflection to recognize as reasonable in our conduct with regard to one another. … all persons … even … persons who are not contemporaries but who belong to many generations. Thus to see our place in society from the perspective of this position is … to regard the human situation not only from all social but also from all temporal points of view. The perspective of eternity is not a perspective from a certain place beyond the world, nor the point of view of a transcendent being; rather it is a certain form of thought and feeling that rational persons can adopt within the world. … Purity of heart, if one could attain it, would be to see clearly and to act with grace and self-command from this point of view.” Fedorov wrote: “By refusing to grant ourselves the right to set ourselves apart … we are kept from setting any goal for ourselves that is not the common task of all.” But Fedorov’s thought soars beyond the present world to a world of its own, in his insistence that we can become immortal and godlike through rational efforts, and that our moral obligation is to create a heaven to be shared by all who ever lived.

Table of Contents

1. Life

Russian philosopher, teacher, and librarian Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov was born June 9, 1829, and died December 28, 1903. He was founder of an immortalist (anti-death) philosophy emphasizing “the common task” of resurrecting the dead through scientific means. Since the end of the Cold War, his thought has received renewed interest and advocacy in Russia and elsewhere — for example, in connection with cryonics (cryonic hibernation) and prolongevity. Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov (alternative romanized spellings are possible — for example: Nicholas Fyodorovich Fyodorov) advocated the ethical priority of a research and development project he called “the common task,” by which he meant the universal physical resurrection of the dead by future advances in science and technology. He was highly praised by such people as Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy (literature), Afanasi Fet (poetry), and Konstantin Tsiolkowsky (astronautics), yet he is not well known in the West, despite some limited interest. The illegitimate son of Prince Pavel Ivanovich Gagarin and Elisaveta Ivanova, a woman of lower-class nobility, Nikolai (with his mother and her other children) had to leave his father’s home at age four, due to the prince’s death. The family continued to be well cared for, however. Beginning in 1868, he worked for 25 years as a librarian with the Rumiantsev Museum (now the Russian State Library), Moscow; during this period, he was teacher-mentor of the young Konstantin Tsiolkowsky. After retiring, and until his death, he worked in the Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His works, published posthumously, were available (in accordance with the Christian spirit of Fedorov’s philosophy) only free of charge from the publisher, who renounced all rights.

2. Philosophy

Due to his Christian perspective, Fedorov found the widespread lack of love among people appalling. He divided these non-loving relations into two kinds. One is alienation among people: “non-kindred relations of people among themselves.” The other is isolation of the living from the dead: “nature’s non-kindred relation to men.” “[O]ne should live not for oneself nor for others but with all and for all” (Filosofiya Obshchago Dela vol. I, 118, n. 5, as quoted in Zakydalsky, 55). Fedorov is referring to all people of all time (past, present, future). He is speaking of a project to unite humankind, the colonization (“spiritualization”) of the universe, the quest for the Kingdom of God, the creation of cosmos from chaos, the death of death, even resurrection of the dead. Fedorov believed, and passionately felt, that resignation in the face of death and separation of knowledge from action was false Christianity. He cautioned against being fooled into worshipping the blind forces of Satan. Rather, one should actively participate in changing what is into what ought to be.

The division between the learned and the unlearned was, in Fedorov’s view, worse than the separation of the rich and the poor. The unlearned are more concerned with work than thought. The learned (philosophers and scientists) are less concerned with work than thought. The learned seem unaware that ideas “are not subjective, nor are they objective; they are projective.” Philosophers and scientists, because they have separated ideas from moral action, are simply slaves to the imperfect present order. It is a root dogma of the learned that paradise is not possible. The unlearned should demand that the learned (because only they have the necessary knowledge) become a temporary task force for the Kingdom of God. The learned, however, will attempt to persuade us that problems like crop failures, disease, and death are not general questions but matters for a narrow discipline, questions for only a very small (or nonexistent) minority of the learned. Separation of the learned from the masses turns them into a seemingly permanent class, producing non-lovers of humankind. The “transformation of the blind course of nature into one that is rational … is bound to appear to the learned as a disruption of order, although this order of theirs brings only disorder among men, striking them down with famine, plague, and death.”

A citizen, a comrade, or a team-member can be replaced by another. However a person loved, one’s kin, is irreplaceable. Moreover, memory of one’s dead kin is not the same as the real person. Pride in one’s forefathers is a vice, a form of egotism. On the other hand, love of one’s forefathers means sadness in their death, requiring the literal raising of the dead. Politics must be replaced by physics. The politics of egoism and altruism must be replaced by Christianity which “knows only all men.” Pride is a Tower of Babel that separates us from one another. Love is a “fusion as opposed to a confusion.” For Fedorov, “complete and universal salvation” is preferable to “incomplete or non-universal salvation in which some men — the sinners — are condemned to eternal torments and others — the righteous — to an eternal contemplation of these torments.” That is to say, Fedorov’s bold science project, “the common task,” is not the only possible route to salvation. “Salvation may also occur without the participation of men … if they do not unite in the common task”; “if we do not unite to accomplish our salvation, if we do not accept the Gospel message,” then a “purely transcendent resurrection will save only the elect; for the rest it will be an expression of God’s wrath,” “eternal punishment.” “I believe this literally.” “Christianity has not fully saved the world, because it has not been fully assimilated.” Christianity “is not simply a doctrine of redemption, but the very task of redemption.”

Fedorov’s thoughts have been variously described as bold, culminating, curious, easily-misunderstood, extreme, hazy, idealist, naive, of-value, scientifico-magical, special, unexpected, unique, and utopian. Many of the small number of philosophers familiar with Fedorov admit his originality, his independence, his human concern, perhaps even his logic — up to a point. But his resurrection project is viewed with understandable skepticism and often dismissed as an impossible fantasy. Interestingly, the harshest criticism has come from Christian thinkers such as Florovsky and Ustryalov whose objections bear religious overtones; some materialists such as Muravyov and Setnitsky have been quite benign and favorable by comparison. Perhaps all would agree, however, on Fedorov’s single-mindedness. Looked at positively, this is simply another term for purity-of-heart, a quality of saintliness. With his strong emphasis on kinship and brotherhood demanding, ultimately, a world in which all must mutually benefit, Fedorov perhaps anticipates Rawls who says: “Thus what we are doing is to combine into one conception the totality of conditions that we are ready upon due reflection to recognize as reasonable in our conduct with regard to one another. … all persons … even … persons who are not contemporaries but who belong to many generations. Thus to see our place in society from the perspective of this position is … to regard the human situation not only from all social but also from all temporal points of view. The perspective of eternity is not a perspective from a certain place beyond the world, nor the point of view of a transcendent being; rather it is a certain form of thought and feeling that rational persons can adopt within the world. … Purity of heart, if one could attain it, would be to see clearly and to act with grace and self-command from this point of view.” Fedorov wrote: “By refusing to grant ourselves the right to set ourselves apart … we are kept from setting any goal for ourselves that is not the common task of all.” But Fedorov’s thought soars beyond the present world to a world of its own, in his insistence that we can become immortal and godlike through rational efforts, and that our moral obligation is to create a heaven to be shared by all who ever lived. “[D]eath is merely the result or manifestation of our infantilism, lack of independence and self-reliance, and of our incapacity for mutual support and the restoration of life. People are still minors, half-beings, whereas the fullness of personal existence, personal perfection, is possible. However, it is possible only within general perfection. Coming of age will bring perfect health and immortality, but for the living [living contemporaries of Fedorov] immortality is impossible without the resurrection of the dead”(What Was Man Created For?, 76).

3. Further Reading

(Collected Works in Russian)

- Fedorov, N. F. Filosofiya Obshchago Dela: Stat’i, Mysli, i Pis’ma Nikolaia Fedorovicha Fedorova, ed. V. A. Kozhevnikov and N. P. Peterson, 2 vols. originally published by Fedorov’s friends and followers after his death, 1906, 1913; reprint London: Gregg Press, 1970.

- Fedorov, N. F. Sobranie Sochineniy, 4 vols. + supp. Moscow: Traditsiya, 2000.

(Works in English)

- Berdyaev, N. A. “N. F. Fyodorov.” The Russian Review 9 (1950) 124-130.

- Fedorov’s thought was not without influence on Berdyaev’s existentialism.

- Berdyaev, N. A. The Russian Idea. New York: Macmillan Co., 1948.

- Fedorov and other original Russian thinkers are discussed.

- Fedorov, N. F. “The Question of Brotherhood or Kinship, of the Reasons for the Unbrotherly, Unkindred, or Unpeaceful State of the World, and of the Means for the Restoration of Kinship” in Edie, J. M.; Scanlan, J. P.; Zeldin, M.; and Kline, G. L., eds. Russian Philosophy. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1965. 16-54.

- This is one place to begin if you want to read Fedorov directly (in English translation).

- Fedorov, N. F. What Was Man Created For? The Philosophy of the Common Task: Selected Works. Koutiassov, E.; and Minto, M., eds. Lausanne, Switzerland: Honeyglen/L’Age d’Homme, 1990.

- A good source of Fedorov in English translation; includes a list of Russian language works in the bibliography.

- Lossky, N. O. History of Russian Philosophy. New York: International Universities Press, 1951.

- Fedorov is included in this history.

- Lukashevich, S. N. F. Fedorov (1828-1903): A Study in Russian Eupsychian and Utopian Thought. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1977.

- The methodology used in this study may not insure full appreciation of Fedorov’s thought, but it does demonstrate that his thought was indeed a detailed, coherent philosophy in which the various pieces fit together.

- Schmemann, A., ed. Ultimate Questions: An Anthology of Modern Russian Religious Thought. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965; reprint Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1977.

- Selections (translations) from Russian religious thinkers, including Fedorov, concerned with eschatology or other “ultimate” questions. The Fedorov material is from vol. 1 of Filosofiya Obshchago Dela and deals with “the restoration of kinship among mankind.”

- Soloviov, M. “The ‘Russian Trace’ in the History of Cryonics,” Cryonics 16:4 (4th Quarter, 1995) 20-23.

- Closing paragraph describes author’s then-current (post-cold-war) and perhaps unprecedented efforts promoting cryonics and immortalism in the former Soviet Union; the article itself acknowledges a debt to Fedorov.

- Young, G. M. Nikolai F. Fedorov: An Introduction. Belmont, Mass.: Nordland Publishing Co., 1979.

- Not only an excellent introduction, but a mine of references and information inviting further Fedorovian research, including Russian language works, many of which are not yet translated (or not fully translated) into English.

- Zakydalsky, T. D. N. F. Fyodorov’s Philosophy of Physical Resurrection. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI, 1976.

- A Ph.D. dissertation (Bryn Mawr) of 531 pages. Bibliography has a list of Russian language works.

- Zenkovsky, V. V. A History of Russian Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press, 1953.

- Fedorov is included in this history.

Author Information

Charles Tandy

Email: cetandy@gmail.com

Ria University

U. S. A.

R. Michael Perry

Email: mike@alcor.org

U. S. A.