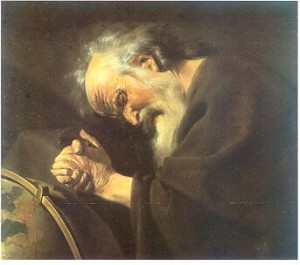

Heraclitus (fl. c. 500 B.C.E.)

A Greek philosopher of the late 6th century BCE, Heraclitus criticizes his predecessors and contemporaries for their failure to see the unity in experience. He claims to announce an everlasting Word (Logos) according to which all things are one, in some sense. Opposites are necessary for life, but they are unified in a system of balanced exchanges. The world itself consists of a law-like interchange of elements, symbolized by fire. Thus the world is not to be identified with any particular substance, but rather with an ongoing process governed by a law of change. The underlying law of nature also manifests itself as a moral law for human beings. Heraclitus is the first Western philosopher to go beyond physical theory in search of metaphysical foundations and moral applications.

A Greek philosopher of the late 6th century BCE, Heraclitus criticizes his predecessors and contemporaries for their failure to see the unity in experience. He claims to announce an everlasting Word (Logos) according to which all things are one, in some sense. Opposites are necessary for life, but they are unified in a system of balanced exchanges. The world itself consists of a law-like interchange of elements, symbolized by fire. Thus the world is not to be identified with any particular substance, but rather with an ongoing process governed by a law of change. The underlying law of nature also manifests itself as a moral law for human beings. Heraclitus is the first Western philosopher to go beyond physical theory in search of metaphysical foundations and moral applications.

Table of Contents

- Life and Times

- Theory of Knowledge

- The Doctrine of Flux and the Unity of Opposites

- Criticism of Ionian Philosophy

- Physical Theory

- Moral and Political Theory

- Accomplishments and Influence

- References and Further Reading

1. Life and Times

Heraclitus lived in Ephesus, an important city on the Ionian coast of Asia Minor, not far from Miletus, the birthplace of philosophy. We know nothing about his life other than what can be gleaned from his own statements, for all ancient biographies of him consist of nothing more than inferences or imaginary constructions based on his sayings. Although Plato thought he wrote after Parmenides, it is more likely he wrote before Parmenides. For he criticizes by name important thinkers and writers with whom he disagrees, and he does not mention Parmenides. On the other hand, Parmenides in his poem arguably echoes the words of Heraclitus. Heraclitus criticizes the mythographers Homer and Hesiod, as well as the philosophers Pythagoras and Xenophanes and the historian Hecataeus. All of these figures flourished in the 6th century BCE or earlier, suggesting a date for Heraclitus in the late 6th century. Although he does not speak in detail of his political views in the extant fragments, Heraclitus seems to reflect an aristocratic disdain for the masses and favor the rule of a few wise men, for instance when he recommends that his fellow-citizens hang themselves because they have banished their most prominent leader (DK22B121 in the Diels-Kranz collection of Presocratic sources).

2. Theory of Knowledge

Heraclitus sees the great majority of human beings as lacking understanding:

Of this Word’s being forever do men prove to be uncomprehending, both before they hear and once they have heard it. For although all things happen according to this Word they are like the unexperienced experiencing words and deeds such as I explain when I distinguish each thing according to its nature and declare how it is. Other men are unaware of what they do when they are awake just as they are forgetful of what they do when they are asleep. (DK22B1)

Most people sleep-walk through life, not understanding what is going on about them. Yet experience of words and deeds can enlighten those who are receptive to their meaning. (The opening sentence is ambiguous: does the ‘forever’ go with the preceding or the following words? Heraclitus prefigures the semantic complexity of his message.)

On the one hand, Heraclitus commends sense experience: “The things of which there is sight, hearing, experience, I prefer” (DK22B55). On the other hand, “Poor witnesses for men are their eyes and ears if they have barbarian souls” (DK22B107). A barbarian is one who does not speak the Greek language. Thus while sense experience seems necessary for understanding, if we do not know the right language, we cannot interpret the information the senses provide. Heraclitus does not give a detailed and systematic account of the respective roles of experience and reason in knowledge. But we can learn something from his manner of expression.

Describing the practice of religious prophets, Heraclitus says, “The Lord whose oracle is at Delphi neither reveals nor conceals, but gives a sign” (DK22B93). Similarly, Heraclitus does not reveal or conceal, but produces complex expressions that have encoded in them multiple messages for those who can interpret them. He uses puns, paradoxes, antitheses, parallels, and various rhetorical and literary devices to construct expressions that have meanings beyond the obvious. This practice, together with his emphasis on the Word (Logos) as an ordering principle of the world, suggests that he sees his own expressions as imitations of the world with its structural and semantic complexity. To read Heraclitus the reader must solve verbal puzzles, and to learn to solve these puzzles is to learn to read the signs of the world. Heraclitus stresses the inductive rather than the deductive method of grasping the world, a world that is rationally structured, if we can but discern its shape.

For those who can discern it, the Word has an overriding message to impart: “Listening not to me but to the Word it is wise to agree that all things are one” (DK22B50). It is perhaps Heraclitus’s chief project to explain in what sense all things are one.

3. The Doctrine of Flux and the Unity of Opposites

According to both Plato and Aristotle, Heraclitus held extreme views that led to logical incoherence. For he held that (1) everything is constantly changing and (2) opposite things are identical, so that (3) everything is and is not at the same time. In other words, Universal Flux and the Identity of Opposites entail a denial of the Law of Non-Contradiction. Plato indicates the source of the flux doctrine: “Heraclitus, I believe, says that all things go and nothing stays, and comparing existents to the flow of a river, he says you could not step twice into the same river” (Cratylus 402a = DK22A6).

What Heraclitus actually says is the following:

On those stepping into rivers staying the same other and other waters flow. (DK22B12)

There is an antithesis between ‘same’ and ‘other.’ The sentence says that different waters flow in rivers staying the same. In other words, though the waters are always changing, the rivers stay the same. Indeed, it must be precisely because the waters are always changing that there are rivers at all, rather than lakes or ponds. The message is that rivers can stay the same over time even though, or indeed because, the waters change. The point, then, is not that everything is changing, but that the fact that some things change makes possible the continued existence of other things. Perhaps more generally, the change in elements or constituents supports the constancy of higher-level structures.As for the alleged doctrine of the Identity of Opposites, Heraclitus does believe in some kind of unity of opposites. For instance, “God is day night, winter summer, war peace, satiety hunger . . .” (DK22B67). But if we look closer, we see that the unity in question is not identity:

As the same thing in us is living and dead, waking and sleeping, young and old. For these things having changed around are those, and conversely those having changed around are these. (DK22B88)

The second sentence in B88 gives the explanation for the first. If F is the same as G because F turns into G, then the two are not identical. And Heraclitus insists on the common-sense truth of change: “Cold things warm up, the hot cools off, wet becomes dry, dry becomes wet” (DK22B126). This sort of mutual change presupposes the non-identity of the terms. What Heraclitus wishes to maintain is not the identity of opposites but the fact that they replace each other in a series of transformations: they are interchangeable or transformationally equivalent.

Thus, Heraclitus does not hold Universal Flux, but recognizes a lawlike flux of elements; and he does not hold the Identity of Opposites, but the Transformational Equivalence of Opposites. The views that he does hold do not, jointly or separately, entail a denial of the Law of Non-Contradiction. Heraclitus does, to be sure, make paradoxical statements, but his views are no more self-contradictory than are the paradoxical claims of Socrates. They are, presumably, meant to wake us up from our dogmatic slumbers.

4. Criticism of Ionian Philosophy

Heraclitus’ theory can be understood as a response to the philosophy of his Ionian predecessors. The philosophers of the city of Miletus (near Ephesus), Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes, believed some original material turns into all other things. The world as we know it is the orderly articulation of different stuffs produced out of the original stuff. For the Milesians, to explain the world and its phenomena was just to show how everything came from the original stuff, such as Thales’ water or Anaximenes’ air.

Heraclitus seems to follow this pattern of explanation when he refers to the world as “everliving fire” (DK22B30, quoted in full in next section) and makes statements such as “Thunderbolt steers all things,” alluding to the directive power of fire (DK22B64). But fire is a strange stuff to make the origin of all things, for it is the most inconstant and changeable. It is, indeed, a symbol of change and process. Heraclitus observes,

All things are an exchange for fire, and fire for all things, as goods for gold and gold for goods. (DK22B90)

We can measure all things against fire as a standard; there is an equivalence between all things and gold, but all things are not identical to gold. Similarly, fire provides a standard of value for other stuffs, but it is not identical to them. Fire plays an important role in Heraclitus’ system, but it is not the unique source of all things, because all stuffs are equivalent.

Ultimately, fire may be more important as a symbol than as a stuff. Fire is constantly changing-but so is every other stuff. One thing is transformed into another in a cycle of changes. What is constant is not some stuff, but the overall process of change itself. There is a constant law of transformations, which is, perhaps, to be identified with the Logos. Heraclitus may be saying that the Milesians correctly saw that one stuff turns into another in a series, but they incorrectly inferred from this that some one stuff is the source of everything else. But if A is the source of B and B of C, and C turns back into B and then A, then B is likewise the source of A and C, and C is the source of A and B. There is no particular reason to promote one stuff at the expense of the others. What is important about the stuffs is that they change into others. The one constant in the whole process is the law of change by which there is an order and sequence to the changes. If this is what Heraclitus has in mind, he goes beyond the physical theory of his early predecessors to arrive at something like a process philosophy with a sophisticated understanding of metaphysics.

5. Physical Theory

Heraclitus’ criticisms and metaphysical speculations are grounded in a physical theory. He expresses the principles of his cosmology in a single sentence:

This world-order, the same of all, no god nor man did create, but it ever was and is and will be: everliving fire, kindling in measures and being quenched in measures. (DK22B30)

This passage contains the earliest extant philosophical use of the word kosmos, “world-order,” denoting the organized world in which we live, with earth, sea, atmosphere, and heavens. While ancient sources understand Heraclitus as saying the world comes to be and then perishes in a fiery holocaust, only to be born again (DK22A10), the present passage seems to contradict this reading: the world itself does not have a beginning or end. Parts of it are being consumed by fire at any given time, but the whole remains. Almost all other early cosmologists before and after Heraclitus explained the existence of the ordered world by recounting its origin out of elemental stuffs. Some also predicted the extinction of the world. But Heraclitus, the philosopher of flux, believes that as the stuffs turn into one another, the world itself remains stable. How can that be?

Heraclitus explains the order and proportion in which the stuffs change:

The turnings of fire: first sea, and of sea, half is earth, half firewind (prêstêr: some sort of fiery meteorological phenomenon). (DK22B31a)

Sea is liquefied and measured into the same proportion as it had before it became earth. (DK22B31b)

Fire is transformed into water (“sea”) of which half turns back into fire (“firewind”) and half into earth. Thus there is a sequence of stuffs: fire, water, earth, which are interconnected. When earth turns back into sea, it occupies the same volume as it had before it turned into earth. Thus we can recognize a primitive law of conservation-not precisely conservation of matter, at least the identity of the matter is not conserved, nor of mass, but at least an equivalence of matter is maintained. Although the fragments do not give detailed information about Heraclitus’ physics, it seems likely that the amount of water that evaporates each day is balanced by the amount of stuff that precipitates as water, and so on, so that a balance of stuffs is maintained even though portions of stuff are constantly changing their identity.

For Heraclitus, flux and opposition are necessary for life. Aristotle reports,

Heraclitus criticizes the poet who said, ‘would that strife might perish from among gods and men’ [Homer Iliad 18.107]’ for there would not be harmony without high and low notes, nor living things without female and male, which are opposites. (DK22A22)

Heraclitus views strife or conflict as maintaining the world:

We must recognize that war is common and strife is justice, and all things happen according to strife and necessity. (DK22B80)

War is the father of all and king of all, who manifested some as gods and some as men, who made some slaves and some freemen. (DK22B53)

In a tacit criticism of Anaximander, Heraclitus rejects the view that cosmic justice is designed to punish one opposite for its transgressions against another. If it were not for the constant conflict of opposites, there would be no alternations of day and night, hot and cold, summer and winter, even life and death. Indeed, if some things did not die, others would not be born. Conflict does not interfere with life, but rather is a precondition of life.

As we have seen, for Heraclitus fire changes into water and then into earth; earth changes into water and then into fire. At the level of either cosmic bodies (in which sea turns into fiery storms on the one hand and earth on the other) or domestic activities (in which, for instance, water boils out of a pot), there is constant flux among opposites. To maintain the balance of the world, we must posit an equal and opposite reaction to every change. Heraclitus observes,

The road up and down is one and the same. (DK22B60)

Here again we find a unity of opposites, but no contradiction. One road is used to pursue two different routes. Daily traffic carries some travelers out of the city, while it brings some back in. The image applies equally to physical theory: as earth changes to fire, fire changes to earth. And it may apply to psychology and other domains as well.

6. Moral and Political Theory

There has been some debate as to whether Heraclitus is chiefly a philosopher of nature (a view championed by G. S. Kirk) or a philosopher concerned with the human condition (C. H. Kahn). The opening words of Heraclitus’ book (DK22B1, quoted above) seem to indicate that he will expound the nature of things in a way that will have profound implications for human life. In other words, he seems to see the theory of nature and the human condition as intimately connected. In fact, recently discovered papyri have shown that Heraclitus is concerned with technical questions of astronomy, not only with general theory. There is no reason, then, to think of him as solely a humanist or moral philosopher. On the other hand, it would be wrong to think of him as a straightforward natural philosopher in the manner of other Ionian philosophers, for he is deeply concerned with the moral implications of physical theory.

Heraclitus views the soul as fiery in nature:

To souls it is death to become water, to water death to become earth, but from earth water is born, and from water soul. (DK22B36)

Soul is generated out of other substances just as fire is. But it has a limitless dimension:

If you went in search of it, you would not find the boundaries of the soul, though you traveled every road-so deep is its measure [logos]. (DK22B45)

Drunkenness damages the soul by causing it to be moist, while a virtuous life keeps the soul dry and intelligent. Souls seem to be able to survive death and to fare according to their character.

The laws of a city-state are an important principle of order:

The people [of a city] should fight for their laws as they would for their city wall. (DK22B44)

Speaking with sense we must rely on a common sense of all things, as a city relies on its wall, and much more reliably. For all human laws are nourished by the one divine law. For it prevails as far as it will and suffices for all and overflows. (DK22B114)

The laws provide a defense for a city and its way of life. But the laws are not merely of local interest: they derive their force from a divine law. Here we see the notion of a law of nature that informs human society as well as nature. There is a human cosmos that like the natural cosmos reflects an underlying order. The laws by which human societies are governed are not mere conventions, but are grounded in the ultimate nature of things. One cannot break a human law with impunity. The notion of a law-like order in nature has antecedents in the theory of Anaximander, and the notion of an inherent moral law influences the Stoics in the 3rd century BCE.

Heraclitus recognizes a divine unity behind the cosmos, one that is difficult to identify and perhaps impossible to separate from the processes of the cosmos:

The wise, being one thing only, would and would not take the name of Zeus [or: Life]. (DK22B32)

God is day night, winter summer, war peace, satiety hunger, and it alters just as when it is mixed with incense is named according to the aroma of each. (DK22B67)

Evidently the world either is god, or is a manifestation of the activity of god, which is somehow to be identified with the underlying order of things. God can be thought of as fire, but fire, as we have seen, is constantly changing, symbolic of transformation and process. Divinity is present in the world, but not as a conventional anthropomorphic being such as the Greeks worshiped.

7. Accomplishments and Influence

Heraclitus goes beyond the natural philosophy of the other Ionian philosophers to make profound criticisms and develop far-reaching implications of those criticisms. He suggests the first metaphysical foundation for philosophical speculation, anticipating process philosophy. And he makes human values a central concern of philosophy for the first time. His aphoristic manner of expression and his manner of propounding general truths through concrete examples remained unique.

Heraclitus’s paradoxical exposition may have spurred Parmenides’ rejection of Ionian philosophy. Empedocles and some medical writers echoed Heraclitean themes of alteration and ongoing process, while Democritus imitated his ethical observations. Influenced by the teachings of the Heraclitean Cratylus, Plato saw the sensible world as exemplifying a Heraclitean flux. Plato and Aristotle both criticized Heraclitus for a radical theory that led to a denial of the Law of Non-Contradiction. The Stoics adopted Heraclitus’s physical principles as the basis for their theories.

8. References and Further Reading

- Barnes, Jonathan. The Presocratic Philosophers. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982, vol. 1, ch. 4.

- Uses modern arguments to defend the traditional view, going back to Plato and Aristotle, that Heraclitus’ commitment to the flux doctrine and the identity of opposites results in an incoherent theory.

- Graham, Daniel W. “Heraclitus’ Criticism of Ionian Philosophy.” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 15 (1997): 1-50.

- Defends Heraclitus against the traditional view held by Barnes and others, and argues that his theory can be understood as a coherent criticism of earlier Ionian philosophy.

- Hussey, Edward. “Epistemology and Meaning in Heraclitus.” Language and Logos. Ed. M. Schofield and M. C. Nussbaum. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1982. 33-59.

- Studies Heraclitus’ theory of knowledge.

- Kahn, Charles H. The Art and Thought of Heraclitus. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1979.

- An important reassessment of Heraclitus that recognizes the literary complexity of his language as a key to interpreting his message. Focuses on Heraclitus as a philosopher of the human condition.

- Kirk, G. S. Heraclitus: The Cosmic Fragments. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1954.

- Focuses on Heraclitus as a natural philosopher.

- Marcovich, Miroslav. Heraclitus: Greek Text with a Short Commentary. Merida, Venezuela: U. of the Andes, 1967.

- A very thorough edition of Heraclitus, which effectively sorts out fragments from reports and reactions.

- Mourelatos, Alexander P. D. “Heraclitus, Parmenides, and the Naive Metaphysics of Things.” Exegesis and Argument. Ed. E. N. Lee et al. Assen: Van Gorcum, 1973. 16-48.

- Examines Heraclitus’ response to the pre-philosophical understanding of things.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. “Psychê in Heraclitus.” Phronesis 17 (1972): 1-16, 153-70.

- Good treatment of Heraclitus’ conception of soul.

- Robinson, T. M. Heraclitus: Fragments. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1987.

- Good brief edition with commentary.

- Vlastos, Gregory. “On Heraclitus.” American Journal of Philology 76 (1955): 337-68. Reprinted in G. Vlastos, Studies in Greek Philosophy, vol. 1, Princeton: Princeton U. Pr., 1995.

- Vigorous defense of the traditional interpretation of Heraclitus against Kirk and others.

Author Information

Daniel W. Graham

Email: daniel_graham@byu.edu

Brigham Young University

U. S. A.