Karl Popper: Political Philosophy

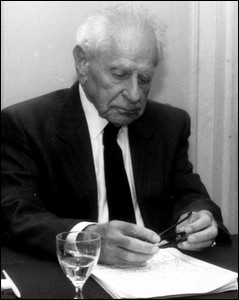

Among philosophers, Karl Popper (1902-1994) is best known for his contributions to the philosophy of science and epistemology. Most of his published work addressed philosophical problems in the natural sciences, especially physics; and Popper himself acknowledged that his primary interest was nature and not politics. However, his political thought has arguably had as great an impact as has his philosophy of science. This is certainly the case outside of the academy. Among the educated general public, Popper is best known for his critique of totalitarianism and his defense of freedom, individualism, democracy and an “open society.” His political thought resides squarely within the camp of Enlightenment rationalism and humanism. He was a dogged opponent of totalitarianism, nationalism, fascism, romanticism, collectivism, and other kinds of (in Popper’s view) reactionary and irrational ideas.

Among philosophers, Karl Popper (1902-1994) is best known for his contributions to the philosophy of science and epistemology. Most of his published work addressed philosophical problems in the natural sciences, especially physics; and Popper himself acknowledged that his primary interest was nature and not politics. However, his political thought has arguably had as great an impact as has his philosophy of science. This is certainly the case outside of the academy. Among the educated general public, Popper is best known for his critique of totalitarianism and his defense of freedom, individualism, democracy and an “open society.” His political thought resides squarely within the camp of Enlightenment rationalism and humanism. He was a dogged opponent of totalitarianism, nationalism, fascism, romanticism, collectivism, and other kinds of (in Popper’s view) reactionary and irrational ideas.

Popper’s rejection of these ideas was anchored in a critique of the philosophical beliefs that, he argued, underpinned them, especially a flawed understanding of the scientific method. This approach is what gives Popper’s political thought its particular philosophical interest and originality—and its controversy, given that he locates the roots of totalitarianism in the ideas of some of the West’s most esteemed philosophers, ancient as well as modern. His defense of a freed and democratic society stems in large measure from his views on the scientific method and how it should be applied to politics, history and social science. Indeed, his most important political texts—The Poverty of Historicism (1944) and The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945)—offer a kind of unified vision of science and politics. As explained below, the people and institutions of the open society that Popper envisioned would be imbued with the same critical spirit that marks natural science, an attitude which Popper called critical rationalism. This openness to analysis and questioning was expected to foster social and political progress as well as to provide a political context that would allow the sciences to flourish.

Table of Contents

- The Critique of the Closed Society

- Freedom, Democracy and the Open Society

- References and Further Reading

1. The Critique of the Closed Society

A central aim of The Open Society and Its Enemies as well as The Poverty of Historicism was to explain the origin and nature of totalitarianism. In particular, the rise of fascism, including in Popper’s native Austria, and the ensuing Second World War prompted Popper to begin writing these two essays in the late 1930s and early 1940s, while he was teaching in New Zealand. He described these works as his “war effort” (Unended Quest, 115).

The arguments in the two essays overlap a great deal. (In fact, The Open Society began as a chapter for Poverty.) Yet there is a difference in emphasis. The Poverty of Historicism is concerned principally with the methodology of the social sciences, and, in particular, how a flawed idea, which Popper dubbed “historicism,” had led historians and social scientists astray methodologically and which also served as a handmaiden to tyranny. The Open Society, a much longer and, according to Popper, a more important work, included in-depth discussion of historicism and the methods of the social sciences. But it also featured an inquiry into the psychological and historical origins of totalitarianism, which he located in the nexus of a set of appealing but, he argued, false ideas. These included not only historicism but also what he labeled “holism” and “essentialism.” Together they formed the philosophical substrate of what Popper called the “closed society.” The “closed society” is what leads to totalitarianism.

a. Open versus Closed Societies

According to Popper, totalitarianism was not unique to the 20th century. Rather, it “belongs to a tradition which is just as old or just as young as our civilization itself” (Open Society, Vol. I, 1). In The Open Society, Popper’s search for the roots of totalitarianism took him back to ancient Greece. There he detected the emergence of what he called the first “open society” in democratic Athens of the 5th century B.C.E., Athenians, he argued, were the first to subject their own values, beliefs, institutions and traditions to critical scrutiny and Socrates and the city’s democratic politics exemplified this new attitude. But reactionary forces were unnerved by the instability and rapid social change that an open society had unleashed. (Socrates was indicted on charges of corrupting the youth and introducing new gods.) They sought to turn back the clock and return Athens to a society marked by rigid class hierarchy, conformity to the customs of the tribe, and uncritical deference to authority and tradition—a “closed society.” This move back to tribalism was motivated by a widely and deeply felt uneasiness that Popper called the “strain of civilization.” The structured and organic character of closed societies helps to satisfy a deep human need for regularity and a shared common life, Popper said. In contrast, the individualism, freedom and personal responsibility that open societies necessarily engender leave many feeling isolated and anxious, but this anxiety, Popper said, must be born if we are to enjoy the greater benefits of living in an open society: freedom, social progress, growing knowledge, and enhanced cooperation. “It is the price we have to pay for being human” (Open Society Vol. 1, 176).

Popper charged that Plato emerged as the philosophical champion of the closed society and in the process laid the groundwork for totalitarianism. Betraying the open and critical temper of his mentor Socrates, in his Republic Plato devised an elaborate system that would arrest all political and social change and turn philosophy into an enforcer, rather than a challenger, of authority. It would also reverse the tide of individualism and egalitarianism that had emerged in democratic Athens, establishing a hierarchical system in which the freedom and rights of the individual would be sacrificed to the collective needs of society.

Popper noted that Plato’s utopian vision in the Republic was in part inspired by Sparta, Athen’s enemy in the Peloponnesian War and, for Popper, an exemplar of the closed society. Spartan society focused almost exclusively on two goals: internal stability and military prowess. Toward these ends, the Spartan constitution sought to create a hive-like, martial society that always favored the needs of the collective over the individual and required a near total control over its citizenry. This included a primitive eugenics, in which newborn infants deemed insufficiently vigorous were tossed into a pit of water. Spartan males judged healthy enough to merit life were separated from their families at a young age and provided an education consisting mainly of military training. The training produced fearsome warriors who were indifferent to suffering, submissive to authority, and unwaveringly loyal to the city. Fighting for the city was an honor granted solely to the male citizenry, while the degrading toil of cultivating the land was the lot reserved to an enslaved tribe of fellow Greeks, the helots. Rigid censorship was imposed on the citizenry, as well as laws that strictly limited contact with foreigners. Under this system, Sparta became a dominant military power in ancient Greece, but, unsurprisingly, made no significant contributions to the arts and sciences. Popper described Sparta as an “arrested tribalism” that sought to stymie “equalitarian, democratic and individualistic ideologies,” such as found in Athens (Open Society Vol. 1, 182). It was no coincidence, he said, that the Nazis and other modern-day totalitarians were also inspired by the Spartans.

b. Holism, Essentialism and Historicism

Popper charged that three deep philosophical predispositions underpinned Plato’s defense of the closed society and, indeed, subsequent defenses of the closed society during the next two-and-a-half millennia. These ideas were holism, essentialism, and historicism.

Holism may be defined as the view that adequate understanding of certain kinds of entities requires understanding them as a whole. This is often held to be true for biological and social systems, for example, an organism, an ecosystem, an economy, or a culture. A corollary that is typically held to follow from this view is that such entities have properties that cannot be reduced to the entities’ constituent parts. For instance, some philosophers argue that human consciousness is an emergent phenomenon whose properties cannot be explained solely by the properties of the physical components (nerve cells, neurotransmitters, and so forth) that comprise the human brain. Similarly, those who advocate a holistic approach to social inquiry argue that social entities cannot be reduced to the properties of the individuals that comprise them. That is, they reject methodological individualism and support methodological holism, as Popper called it.

Plato’s holism, Popper argued, was reflected in his view that the city—the Greek polis—was prior to and, in a sense, more real than the individuals who resided in it. For Plato “[o]nly a stable whole, the permanent collective, has reality, not the passing individuals” (Open Society Vol. 1, 80). This view in turn implied that the city has real needs that supersede those of individuals and was thus the source of Plato’s ethical collectivism. According to Popper, Plato believed that a just society required individuals to sacrifice their needs to the interests of the state. “Justice for [Plato],” he wrote, “is nothing but health, unity and stability of the collective body” (OSE I, 106). Popper saw this as profoundly dangerous. In fact, he said, the view that some collective social entity—be it, for example, a city, a state, society, a nation, or a race—has needs that are prior and superior to the needs of actual living persons is a central ethical tenet of all totalitarian systems, whether ancient or modern. Nazis, for instance, emphasized the needs of the Aryan race to justify their brutal policies, whereas communists in the Soviet Union spoke of class aims and interests as the motor of history to which the individual must bend. The needs of the race or class superseded the needs of individuals. In contrast, Popper held, members of an open society see the state and other social institutions as human designed, subject to rational scrutiny, and always serving the interests of individuals—and never the other way around. True justice entails equal treatment of individuals rather than Plato’s organistic view, in which justice is identified as a well functioning state.

Also abetting Plato’s support for a closed society was a doctrine that Popper named “methodological essentialism”. Adherents of this view claim “that it is the task of pure knowledge or ‘science’ to discover and to describe the true nature of things, i.e., their hidden reality or essence” (Open Society Vol. 1, 31). Plato’s theory of the Forms exemplified this approach. According to Plato, understanding of any kind of thing—for example, a bed, a triangle, a human being, or a city—requires understanding what Plato called its Form. The Forms are timeless, unchanging and perfect exemplars of sensible things found in our world. Coming to understand a Form, Plato believed, requires rational examination of its essence. Such understanding is governed by a kind of intuition rather than empirical inquiry. For instance, mathematical intuition provides the route to understanding the essential nature of triangles—that is, their Form—as opposed to attempting to understand the nature of triangles by measuring and comparing actual sensible triangles found in our world.

Although Forms are eternal and unchanging, Plato held that the imperfect copies of them that we encounter in the sensible world invariably undergo decay. Extending this theory presented a political problem for Plato. In fact, according to Popper, the disposition to decay was the core political problem that Plato’s philosophy sought to remedy. The very nature of the world is such that human beings and the institutions that they create tend to degrade over time. For Plato, this included cities, which he believed were imperfect copies of the Form of the city. This view of the city, informed by Plato’s methodological essentialism, produced a peculiar political science, Popper argued. It required, first, understanding the true and best nature of the city, that is, its Form. Second, in order to determine how to arrest (or at least slow) the city’s decay from its ideal nature, the study of politics must seek to uncover the laws or principles that govern the city’s natural tendency towards decay and thereby to halt the degradation. Thus Plato’s essentialism led him to seek a theory of historical change—a theory that brings order and intelligibility to the constant flux of our world. That is, Plato’s essentialism led to what Popper labeled “historicism.”

Historicism is the view that history is governed by historical laws or principles and, further, that history has a necessary direction and end-point. This being so, historicists believe that the aim of philosophy—and, later, history and social science—must be to predict the future course of society by uncovering the laws or principles that govern history. Historicism is a very old view, Popper said, predating Athens of the 5th century B.C.E. Early Greek versions of historicism held that the development of cities naturally and necessarily moves in cycles: a golden age followed by inevitable decay and collapse, which in some versions paves the way for rebirth and a new golden age. In Plato’s version of this “law of decay,” the ideal city by turns degenerates from timarchy (rule by a military class) to oligarchy to democracy and then, finally, dictatorship. But Plato did not merely describe the gradual degeneration of the city; he offered a philosophical explanation of it, which relied upon his theory of the Forms and thus methodological essentialism. Going further, Plato sought to provide a way to arrest this natural tendency toward decay. This, Popper argued, was the deep aim of the utopian society developed in the Republic—a newly fabricated closed society as the solution to natural tendency toward moral and political decline. It required creation of a rigid and hierarchical class society governed by philosopher kings, whose knowledge of the Forms would stave off decay as well as ensure the rulers’ incorruptibility. Tumultuous democratic Athens would be replaced with a stable and unchanging society. Plato saw this as justice, but Popper argued that it had all the hallmarks of totalitarianism, including rigid hierarchy, censorship, collectivism, central planning—all of which would be reinforced through propaganda and deception, or, as Plato called them, “noble lies.”

Plato’s deep mistrust of democracy was no doubt in part a product of experience. As a young man he saw the citizens of Athens, under the influence of demagogues, back ill-advised military campaigns that ultimately led to the Spartan victory over the city in 404 B.C.E. After democracy was reestablished following the Spartan occupiers’ departure in 403 B.C.E., he witnessed the Athenian people’s vote to execute its wisest citizen, Socrates. Popper as a young man had also witnessed the collapse of democracy, in his native Austria and throughout Europe. But he drew very different lessons from that experience. For him, democracy remained a bulwark against tyranny, not its handmaiden. For reasons explained in the next section, Popper held that by rejecting democracy Plato’s system destroyed not only individual freedom but also the conditions for social, political, scientific and moral progress.

Popper’s criticism of Plato sparked a lively and contentious debate. Prior to publication of The Open Society, Plato was widely regarded as the wellspring of enlightened humanism in the Western tradition. Popper’s recasting of Plato as a proto-fascist was scandalous. Classists rose to Plato’s defense and accused Popper of reading Plato ahistorically, using dubious or tendentious translations of his words, and failing to appreciate the ironic and literary elements in Plato’s dialogues. These criticisms exposed errors in Popper’s scholarship. But Popper was nonetheless successful in drawing attention to potential totalitarian dangers of Plato’s utopianism. Subsequent scholarship could not avoid addressing his arguments.

Although Plato was the principle target of Popper’s criticisms in the Open Society, he also detected dangerous tendencies in other ancient Greek philosophers’ ideas, most notably Aristotle’s. Plato’s greatest student, Popper argued, had inherited his teacher’s essentialism but had given it a teleological twist. Like Plato, Aristotle believed that knowledge of an entity required grasping its essence. However, Plato and Aristotle differed in their understanding of the relationship between an entity’s essence and how that essence was manifested in the sensible world. Plato held that the entities found in the sensible world were imperfect, decaying representation of the Forms. Thus his understanding of history, Popper argued, was ultimately pessimistic: the world degrades over time. Plato’s politics was an attempt to arrest or at least slow this degradation. In contrast, Aristotle understood an entity’s essence as a bundle of potentialities that become manifest as the entity develops through time. An entity’s essence acts as a kind of internal motor that impels the entity toward its fullest development, or what Aristotle called its final cause. The oak tree, for example, is the final cause of an acorn, the end towards which it strives.

Herein Popper detected an implicit historicism in Aristotle’s epistemology. Though Aristotle himself produced no theory of history, his essentialism wedded to his teleology naturally lent itself to the notion that a person’s or a state’s true nature can only be understood as it is revealed through time. “Only if a person or a state develops, and only by way of its history, can we get to know anything about its ‘hidden undeveloped essence’” (Open Society Vol. 1I, 7). Further, Popper argued that Aristotle’s essentialism naturally aligned with the notion of historical destiny: a state’s or a nation’s development is predetermined by its “hidden undeveloped essence.”

Popper believed that he had revealed deep links between ancient Greek philosophy and hostility toward the open society. In Plato’s essentialism, collectivism, holism and historicism, Popper detected the philosophical underpinning for Plato’s ancient totalitarian project. As we shall see in the next section, Popper argued that these very same ideas were at the heart of modern totalitarianism, too. Though for Popper Plato was the most important ancient enemy of the open society, in Aristotle’s teleological essentialism Popper found a key link connecting ancient and modern historicism. In fact, the idea of historical destiny that Aristotle’s thought generated was at the core of the thought of two 19th century philosophers, G.W.F. Hegel and Karl Marx, whom Popper charged with facilitating the emergence of modern closed societies. The “far-reaching historicist consequences” of Aristotle’s essentialism “were slumbering for more than twenty centuries, ‘hidden and undeveloped’,” until the advent of Hegel’s philosophical system (Open Society Vol. 1, 8).

c. Hegel, Marx and Modern Historicism

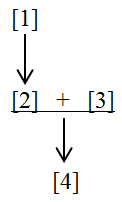

History was central to both Hegel’s and Marx’s philosophy, and for Popper their ideas exemplified historicist thinking and the political dangers that it entailed. Hegel’s historicism was reflected in his view that the dialectal interaction of ideas was the motor of history. The evolution and gradual improvement of philosophical, ethical, political and religious ideas determines the march of history, Hegel argued. History, which Hegel sometimes described as the gradual unfolding of “Reason,” comes to an end when all the internal contradictions in human ideas are finally resolved.

Marx’s historical materialism famously inverted Hegel’s philosophy. For Marx, history was a succession of economic and political systems, or “modes of production” in Marx’s language. As technological innovations and new ways of organizing production led to improvements in a society’s capacity to meet human material needs, new modes of production would emerge. In each new mode of production, the political and legal system, as well as the dominant moral and religious values and practices, would reflect the interests of those who controlled the new productive system. Marx believed that the capitalist mode of production was the penultimate stage of human history. The productive power unleashed by new technologies and factory production under capitalism was ultimately incompatible with capitalism as an economic and political system, which was marked by inefficiency, instability and injustice. Marx predicted that these flaws would inevitably lead to revolution followed by establishment of communist society. This final stage of human development would be one of material abundance and true freedom and equality for all.

According to Popper, though they disagreed on the mechanism that directed human social evolution, both Hegel and Marx, like Plato, were historicists because they believed that trans-historical laws governed human history. This was the key point for Popper, as well as the key error and danger.

The deep methodological flaw of historicism, according to Popper, is that historicists wrongly see the goal of social science as historical forecast—to predict the general course of history. But such prediction is not possible, Popper said. He provided two arguments that he said demonstrated its impossibility. The first was a succinct logical argument: Human knowledge grows and changes overtime, and knowledge in turn affects social events. (That knowledge might be, for example, a scientific theory, a social theory, or an ethical or religious idea.) We cannot predict what we will know in the future (otherwise we would already know it), therefore we cannot predict the future. As long as it is granted that knowledge affects social behavior and that knowledge changes overtime—two premises that Popper considered incontestable—then the view that we can predict the future cannot be true and historicism must be rejected. This argument, it should be noted, also reflected Popper’s judgment that the universe is nondeterministic: that is, he believed that prior conditions and the laws of nature do not completely causally determine the future, including human ideas and actions. Our universe is an “open” universe, he said.

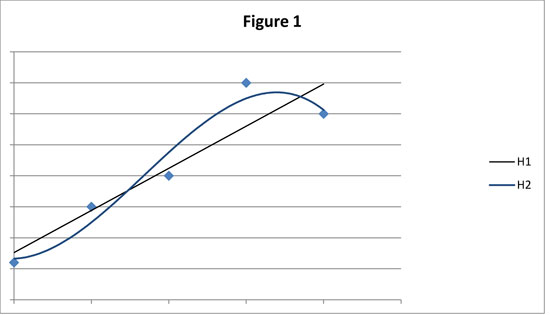

Popper’s second argument against the possibility of historical forecasting focused on the role of laws in social explanations. According to Popper, historicists wrongly believe that genuine social science must be a kind of “theoretical history” in which the aim is to uncover laws of historical development that explain and predict the course of history (Poverty of Historicism, 39). But Popper contended that this represents a fundamental misunderstanding of scientific laws. In fact, Popper argued, there is no such thing as a law of historical development. That is, there are no trans-historical laws that determine the transition from one historical period to the next. Failure to understand why this is so represented a deep philosophical error. There may be sociological laws that govern human behavior within particular social systems or institutions, Popper said. For instance, the laws of supply and demand are kinds of social laws governing market economies. But the future course of history cannot be predicted and, in particular, laws that govern the general trajectory of history do not exist. Popper does not deny that there can be historical trends—a tendency towards greater freedom and equality, more wealth or better technology, for instance, but unlike genuine laws, trends are always dependent upon conditions. Change the conditions and the trends may alter or disappear. A trend towards greater freedom or knowledge could be disrupted by, say, the outbreak of a pandemic disease or the emergence of a new technology that facilitates authoritarian regimes. Popper acknowledges that in certain cases natural scientists can predict the future—even the distance future—with some confidence, as is the case with astronomy, for instance. But this type of successful long-range forecasting can occur only in physical systems that are “well-isolated, stationary and recurrent,” such as the solar system (Conjectures and Refutations, 339). Social systems can never be isolated and stationary, however.

d. Utopian Social Engineering

So historicism as social science is deeply defective, according to Popper. But he also argued that it was politically dangerous and that this danger stemmed from historicism’s natural and close allegiance with what Popper called “utopian social engineering.” Such social planning “aims at remodeling the ‘whole of society’ in accordance with a definite plan or blueprint,” as opposed to social planning that aims at gradual and limited adjustments. Popper admitted that the alliance between historicism and utopian engineering was “somewhat strange” (Poverty of Historicism, 73). Because historicists believe that laws determine the course of history, from their vantage it is ultimately pointless to try to engineer social change. Just as a meteorologist can forecast the weather, but not alter it, the same holds for social scientists, historicists believe. They can predict future social developments, but not cause or alter them. Thus “out-and-out historicism” is against utopian planning—or even against social planning altogether (Open Society Vol. 1, 157). For this reason Marx rejected attempts to design a socialist system; in fact he derided such projects as “utopian.” Nonetheless, the connection between historicism and utopian planning remains strong, Popper insisted. Why?

First, historicism and utopian engineering share a connection to utopianism. Utopians seek to establish an ideal state of some kind, one in which all conflicts in social life are resolved and ultimate human ends—for example, freedom, equality, true happiness—are somehow reconciled and fully realized. Attaining this final goal requires radical overhaul of the existing social world and thus naturally suggests the need for utopian social engineering. Many versions of historicism are thus inclined towards utopianism. As noted above, both Marx’s and Hegel’s theory of history, for instance, predict an end to history in which all social contradictions will be permanently resolved. Second, historicism and utopian social engineering both tend to embrace holism. Popper said that historicists, like utopian engineers, typically believe that “society as a whole” is the proper object of scientific inquiry. For the historicist, society must be understood in terms of social wholes, and to understand the deep forces that move the social wholes, you must understand the laws of history. Thus the historicists’ anticipation of the coming utopia, and their knowledge of the historical tendencies that will bring it about, may tempt them to try to intervene in the historical process and therefore, as Marx said, “lessen the birth pangs” associated with the arrival of the new social order. So while a philosophically consistent historicism might seem to lead to political quiescence, the fact is that historicists often cannot resist political engagement. In addition, Popper noted that even less radical versions of historicism, such as Plato’s, permit human intervention.

Popper argued that utopian engineering, though superficially attractive, is fatally flawed: it invariably leads to multitudinous unintended and usually unwelcome consequences. The social world is so complex, and our understanding of it so incomplete, that the full impact of any imposed change to it, especially grand scale change, can never be foreseen. But, because of their unwarranted faith in their historical prophesies, the utopian engineers will be methodologically ill equipped to deal with this reality. The unintended consequences will be unanticipated, and he or she will be forced to respond to them in a haphazard and ill-informed manner: “[T]he greater the holistic changes attempted, the greater are their unintended and largely unexpected repercussions, forcing on the holistic engineer the expedient of piecemeal improvisation” or the “notorious phenomenon of unplanned planning” (Poverty of Historicism, 68-69). One particularly important cause of unintended consequences that utopian engineers are generally blind to is what Popper called the “human factor” in all institutional design. Institutions can never wholly govern individuals’ behavior, he said, as human choice and human idiosyncrasies will ensure this. Thus no matter how thoroughly and carefully an institution is designed, the fact that institutions are filled with human beings results in a certain degree of unpredictability in their operation. But the historicists’ holism leads them to believe that individuals are merely pawns in the social system, dragged along by larger social forces outside their control. The effect of the human factor is that utopian social engineers inevitably are forced, despite themselves, to try to alter human nature itself in their bid to transform society. Their social plan “substitutes for [the social engineers’] demand that we build a new society, fit for men and women to live in, the demand that we ‘mould’ these men and women to fit into this new society” (Poverty of Historicism, 70).

Achieving such molding requires awesome and total power and thus in this way utopian engineering naturally tends toward the most severe authoritarian dictatorship. But this is not the only reason that utopian engineering and tyranny are allied. The central planning that it requires invariably concentrates power in the hands of the few, or even the one. This is why even utopian projects that officially embrace democracy tend towards authoritarianism. Authoritarian societies are in turn hostile to any public criticism, which deprives the planners of needed feedback about the impact of their policies, which further undermines the effectiveness of utopian engineering. In addition, Popper argued that the utopian planners’ historicism makes them indifferent to the misery that their plans cause. Having uncovered what they believe is inevitable en route to utopia, they all too easily countenance any suffering as a necessary part of that process, and, moreover, they will be inclined to see such suffering as outweighed by the benefits that will flow to all once utopia is reached.

Popper’s discussion of utopian engineering and its link to historicism is highly abstract. His criticisms are generally aimed at “typical” historicists and utopian planners, rather than actual historical or contemporary figures. This reluctance to name names is somewhat surprising, given that Popper himself later stated that the political disasters of the 1930s and 40s were the impetus for his foray into political philosophy. Exactly whom did Popper think was guilty of social science malpractice? A contemporary reader with a passing familiarity with 20th-century history is bound to suppose that Popper had in mind the horrors of the Soviet Union when he discussed utopian planning. Indeed, the attempts to transform the Soviet Union into a modern society—the “five year plans,” rapid industrialization, collectivization of agriculture, and so forth—would seem to feature all the elements of utopian engineering. They were fueled by Marxist historicism and utopianism, centrally planned, aimed at wholesale remodeling of Russian society, and even sought to create a new type of person—“New Soviet Man”—through indoctrination and propaganda. Moreover, the utopian planning had precisely the pernicious effects that Popper predicted. The Soviet Union soon morphed into a brutal dictatorship under Stalin, criticism of the leadership and their programs was ruthlessly suppressed, and the various ambitious social projects were bedeviled by massive unintended consequences. The collectivization of agriculture, for instance, led to a precipitous drop in agricultural production and some 10 million deaths, partly from the unintended consequence of mass starvation and partly from the Soviet leaders’ piecemeal improvisation of murdering incorrigible peasants. However, when writing Poverty and The Open Society, Popper regarded the Soviet experiments, at least the early ones, as examples of piecemeal social planning rather than the utopian kind. His optimistic assessment is no doubt explained partly by his belief at the time that the Russian revolution was a progressive event, and he was thus reluctant to criticize the Soviet Union (Hacohen, 396-397). In any event, the full horrors of the Soviet social experiments were not yet known to the wider world. In addition, the Soviets during the Second World War were part of the alliance against fascism, which Popper saw as a much greater threat to humanity. In fact, initially Popper viewed totalitarianism as an exclusively right-wing phenomenon. However, he later became a unambiguous opponent of Soviet-style communism, and he dedicated the 1957 publication in book form of The Poverty of Historicism to the “memory of the countless men, women and children of all creeds or nations or races who fell victims to the fascist and communist belief in Inexorable Laws of Historical Destiny.”

2. Freedom, Democracy and the Open Society

Having uncovered what he believed were the underlying psychological forces abetting totalitarianism (the strain of civilization) as well as the flawed philosophical ideas (historicism, holism and essentialism), Popper provided his own account of the values and institutions needed to sustain an open society in the contemporary world. He viewed modern Western liberal democracies as open societies and defended them as “the best of all political worlds of whose existence we have any historical knowledge” (All Life Is Problem Solving, 90). For Popper, their value resided principally in the individual freedom that they permitted and their ability to self-correct peacefully over time. That they were democratic and generated great prosperity was merely an added benefit. What gives the concept of an open society its interest is not so much the originality of the political system that Popper advocated, but rather the novel grounds on which he developed and defended this political vision. Popper’s argument for a free and democratic society is anchored in a particular epistemology and understanding of the scientific method. He held that all knowledge, including knowledge of the social world, was conjectural and that freedom and social progress ultimately depended upon the scientific method, which is merely a refined and institutionalized process of trial and error. Liberal democracies in a sense both embodied and fostered this understanding of knowledge and science.

a. Minimalist Democracy

Popper’s view of democracy was simple, though not simplistic, and minimalist. Rejecting the question Who should rule? as the fundamental question of political theory, Popper proposed a new question: “How can we so organize political institutions that bad or incompetent rulers can be prevented from doing too much damage?” (Open Society Vol. 1, 121). This is fundamentally a question of institutional design, Popper said. Democracy happens to be the best type of political system because it goes a long way toward solving this problem by providing a nonviolent, institutionalized and regular way to get rid of bad rulers—namely by voting them out of office. For Popper, the value of democracy did not reside in the fact that the people are sovereign. (And, in any event, he said, “the people do not rule anywhere, it is always governments that rule” [All Life Is Problem Solving, 93]). Rather, Popper defended democracy principally on pragmatic or empirical grounds, not on the “essentialist” view that democracy by definition is rule by the people or on the view that there is something intrinsically valuable about democratic participation. With this move, Popper is able to sidestep altogether a host of traditional questions of democratic theory, e.g.. On what grounds are the people sovereign? Who, exactly, shall count as “the people”? How shall they be represented? The role of the people is simply to provide a regular and nonviolent way to get rid of incompetent, corrupt or abusive leaders.

Popper devoted relatively little thought toward the design of the democratic institutions that permit people to remove their leaders or otherwise prevent them from doing too much harm. But he did emphasize the importance of instituting checks and balances into the political system. Democracies must seek “institutional control of the rulers by balancing their power against other powers” (Ibid.) This idea, which was a key component of the “new science” of politics in the 18th century, was expressed most famously by James Madison in Federalist Paper #51. “A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government,” Madison wrote, “but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.” That is, government must be designed such that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” Popper also argued that two-party systems, such as found in the United States and Great Britain, are superior to proportional representation systems; he reasoned that in a two-party system voters are more easily able to assign failure or credit to a particular political party, that is, the one in power at the time of an election. This in turn fosters self-criticism in the defeated party: “Under such a system … parties are from time to time forced to learn from their mistakes” (All Life Is Problem Solving, 97). For these reasons, government in a two-party system better mirrors the trial-and-error process found in science, leading to better public policy. In contrast, Popper argued that proportional representation systems typically produce multiple parties and coalitional governments in which no single party has control of the government. This makes it difficult for voters to assign responsibility for public policy and thus elections are less meaningful and government less responsive. (It should be noted that Popper ignored that divided government is a typical outcome in the U.S. system. It is relevantly infrequent for one party to control the presidency along with both chambers of the U.S. congress, thus making it difficult for voters to determine responsibility for public policy successes and failures.)

Importantly, Popper’s theory of democracy did not rely upon a well-informed and judicious public. It did not even require that the public, though ill-informed, nonetheless exercises a kind of collective wisdom. In fact, Popper explicitly rejected vox populi vox dei as a “classical myth”. “We are democrats,” Popper wrote, “not because the majority is always right, but because democratic traditions are the least evil ones of which we know” (Conjectures and Refutations, 351). Better than any other system, democracies permit the change of government without bloodshed. Nonetheless Popper expressed the hope that public opinion and the institutions that influence it (universities, the press, political parties, cinema, television, and so forth) could become more rational overtime by embracing the scientific tradition of critical discussion—that is, the willingness to submit one’s ideas to public criticism and habit of listening to another person’s point of view.

b. Piecemeal Social Engineering

So the chief role of the citizen in Popper’s democracy is the small but important one of removing bad leaders. How then is public policy to be forged and implemented? Who forges it? What are its goals? Here Popper introduced the concept of “piecemeal social engineering,” which he offered as a superior approach to the utopian engineering described above. Unlike utopian engineering, piecemeal social engineering must be “small scale,” Popper said, meaning that social reform should focus on changing one institution at a time. Also, whereas utopian engineering aims for lofty and abstract goals (for example, perfect justice, true equality, a higher kind of happiness), piecemeal social engineering seeks to address concrete social problems (for example, poverty, violence, unemployment, environmental degradation, income inequality). It does so through the creation of new social institutions or the redesign of existing ones. These new or reconfigured institutions are then tested through implementation and altered accordingly and continually in light of their effects. Institutions thus may undergo gradual improvement overtime and social ills gradually reduced. Popper compared piecemeal social engineering to physical engineering. Just as physical engineers refine machines through a series of small adjustments to existing models, social engineers gradually improve social institutions through “piecemeal tinkering.” In this way, “[t]he piecemeal method permits repeated experiments and continuous readjustments” (Open Society Vol 1., 163). Only such social experiments, Popper said, can yield reliable feedback for social planners. In contrast, as discussed above, social reform that is wide ranging, highly complex and involves multiple institutions will produce social experiments in which it is too difficult to untangle causes and effects. The utopian planners suffer from a kind of hubris, falsely and tragically believing that they possess reliable experimental knowledge about how the social world operates. But the “piecemeal engineer knows, like Socrates, how little he knows. He knows that we can learn only from our mistakes” (Poverty of Historicism, 67).

Thus, as with his defense of elections in a democracy, Popper’s argument for piecemeal social engineering rests principally on its compatibility with the trial-and-error method of the natural sciences: a theory is proposed and tested, errors in the theory are detected and eliminated, and a new, improved theory emerges, starting the cycle over. Via piecemeal engineering, the process of social progress thus parallels scientific progress. Indeed, Popper says that piecemeal social engineering is the only approach to public policy that can be genuinely scientific: “This—and no Utopian planning or historical prophecy—would mean the introduction of scientific method into politics, since the whole secret of scientific method is a readiness to learn from mistakes” (Open Society Vol 1., 163).

c. Negative Utilitarianism

If piecemeal social engineers should target specific social problems, what criteria should they use to determine which problems are most urgent? Here Popper introduced a concept that he dubbed “negative utilitarianism,” which holds that the principal aim of politics should be to reduce suffering rather than to increase happiness. “[I]t is my thesis,” he wrote, “that human misery is the most urgent problem of a rational public policy” (Conjectures and Refutations, 361). He made several arguments in favor of this view.

First, he claimed that there is no moral symmetry between suffering and happiness: “In my opinion … human suffering makes a direct moral appeal, namely, an appeal for help, while there is no similar call to increase the happiness of a man who is doing well anyway” (Open Society Vol. 1, 284). He added:

A further criticism of the Utilitarian formula ‘Maximize pleasure’ is that it assumes, in principle, a continuous pleasure-pain scale which allows us to treat degrees of pain as negative degrees of pleasure. But, from a moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure, and especially not one man’s pain by another man’s pleasure (Ibid.).

In arguing against what we might call “positive utilitarianism,” Popper stressed the dangers of utopianism. Attempts to increase happiness, especially when guided by some ideal of complete or perfect happiness, are bound to lead to perilous utopian political projects. “It leads invariably to the attempt to impose our scale of ‘higher’ values upon others, in order to make them realize what seems to us of greatest importance for their happiness; in order, as it were to save their souls. It leads to Utopianism and Romanticism” (Open Society Vol 11., 237). In addition, such projects are dangerous because they tend to justify extreme measures, including severe human suffering in the present, as necessary measures to secure a much greater human happiness in the future. “[W]e must not argue that the misery of one generation may be considered as a mere means to the end of securing the lasting happiness of some later generation or generations” (Conjectures and Refutations, 362). Moreover, such projects are doomed to fail anyway, owing to the unintended consequences of social planning and the irreconcilability of the ultimate humans ends of freedom, equality, and happiness. Thus Popper’s rejection of positive utilitarianism becomes part of his broader critique of utopian social engineering, while his advocacy of negative utilitarianism is tied to his support for piecemeal social engineering. It is piecemeal engineering that provides the proper approach to tackling the identifiable, concrete sources of suffering in our world.

Finally, Popper offered the pragmatic argument that negative utilitarianism approach “adds to clarify the field of ethics” by requiring that “we formulate our demands negatively” (Open Society Vol. 1, 285.). Properly understood, Popper says, the aim of science is “the elimination of false theories … rather than the attainment of established truths” (Ibid.). Similarly, ethical public policy may benefit by aiming at “the elimination of suffering rather than the promotion of happiness” (Ibid.). Popper thought that reducing suffering provides a clearer target for public policy than chasing after the will-o’-the-wisp, never-ending goal of increasing happiness. In addition, he argued, it easier to reach political agreement to combat suffering than to increase happiness, thus making effective public policy more likely. “For new ways of happiness are theoretical, unreal things, about which it may be difficult to form an opinion. But misery is with us, here and now, and it will be with us for a long time to come. We all know it from experience” (Conjectures and Refutations, 346). Popper thus calls for a public policy that aims at reducing and, hopefully, eliminating such readily identifiable and universally agreed upon sources of suffering as “poverty, unemployment, national oppression, war, and disease” (Conjectures and Refutations, 361).

d. Libertarian, Conservative or Social Democrat?

Popper’s political thought would seem to fit most comfortably within the liberal camp, broadly understood. Reason, toleration, nonviolence and individual freedom formed the core of his political values, and, as we have seen, he identified modern liberal democracies as the best-to-date embodiment of an open society. But where, precisely, did he reside within liberalism? Here Popper’s thought is difficult to categorize, as it includes elements of libertarianism, conservatism, and socialism—and, indeed, representatives from each of these schools have claimed him for their side.

The case for Popper’s libertarianism rests mainly on his emphasis on freedom and his hostility to large-scale central planning. He insisted that freedom—understood as individual freedom—is the most important political value and that efforts to impose equality can lead to tyranny. “Freedom is more important than equality,” he wrote, and “the attempt to realize equality endangers freedom” (Unended Quest, 36.) Popper also had great admiration for Friedrich Hayek, the libertarian economist from the so-called Austrian school, and he drew heavily upon his ideas in his critique of central planning. However, Popper also espoused many views that would be anathema to libertarians. Although he acknowledged “the tremendous benefit to be derived from the mechanism of free markets,” he seemed to regard economic freedom as important mainly for its instrumental role in producing wealth rather than as an important end in itself (Open Society Vol 11., 124). Further, he warned of the dangers of unbridled capitalism, even declaring that “the injustice and inhumanity of the unrestrained ‘capitalist system’ described by Marx cannot be questioned” (Ibid.). The state therefore must serve as a counteracting force against the predations of concentrated economic power: “We must construct social institutions, enforced by the power of the state, for the protection of the economically weak from the economically strong” (Open Society Vol 11., 125). This meant that the “principle of non-intervention, of an unrestrained economic system, has to be given up” and replaced by “economic interventionism” (Ibid.) Such interventionism, which he also called “protectionism,” would be implemented via the piecemeal social engineering described above. This top-down and technocratic vision of politics is hard to reconcile with libertarianism, whose adherents, following Hayek, tend to believe that such social engineering is generally counterproductive, enlarges the power and thus the danger of the state, and violates individual freedom.

It is in this interventionist role for the state where the socialistic elements of Popper’s political theory are most evident. In his intellectual autobiography Unended Quest, Popper says that he was briefly a Marxist in his youth, but soon rejected the doctrine for what he saw as its adherents’ dogmatism and embrace of violence. Socialism nonetheless remained appealing to him, and he remained a socialist for “several years” after abandoning Marxism (Unended Quest, 36). “For nothing could be better,” he wrote, “than living a modest, simple, and free life in an egalitarian society” (Ibid.). However, eventually he concluded that socialism was “no more than a beautiful dream,” and the dream is undone by the conflict between freedom and equality (Ibid.).

But though Popper saw utopian efforts to create true social and economic equality as dangerous and doomed to fail anyway, he continued to support efforts by the state to reduce and even eliminate the worst effects of capitalism. As we saw above, he advocated the use of piecemeal social engineering to tackle the problems of poverty, unemployment, disease and “rigid class differences.” And it is clear that for Popper the solutions to these problems need not be market-oriented solutions. For instance, he voiced support for establishing a minimum income for all citizens as a means to eliminate poverty. It seems then that his politics put into practice would produce a society more closely resembling the so-called social democracies of northern Europe, with their more generous social welfare programs and greater regulation of industry, than the United States, with its more laissez-faire capitalism and comparatively paltry social welfare programs. That said, it should be noted that in later editions of The Open Society, Popper grew somewhat more leery of direct state intervention to tackle social problems, preferring tinkering with the state’s legal framework, if possible, to address them. He reasoned that direct intervention by the state always empowers the state, which endangers freedom.

Evidence of Popper’s conservatism can be found in his opposition to radical change. His critique of utopian engineering at times seems to echo Edmund Burke’s critique of the French Revolution. Burke depicted the bloodletting of the Terror as an object lesson in the dangers of sweeping aside all institutions and traditions overnight and replacing them with an abstract and untested social blueprint. Also like Burke and other traditional conservatives, Popper emphasized the importance of tradition for ensuring order, stability and well-functioning institutions. People have an inherent need for regularity and thus predictability in their social environment, Popper argued, which tradition is crucial for providing. However, there are important differences between Popper’s and Burke’s understanding of tradition. Popper included Burke, as well as the influential 20th-century conservative Michael Oakeshott, in the camp of the “anti-rationalists.” This is because “their attitude is to accept tradition as something just given”; that is, they “accept tradition uncritically” (Conjectures and Refutations, 120, 122, Popper’s emphasis). Such an attitude treats the values, beliefs and practices of a particular tradition as “taboo.” Popper, in contrast, advocated a “critical attitude” toward tradition (Ibid., Popper’s emphasis). “We free ourselves from the taboo if we think about it, and if we ask ourselves whether we should accept it or reject” (Ibid.). Popper emphasized that a critical attitude does not require stepping outside of all traditions, something Popper denied was possible. Just as criticism in the sciences always targets particular theories and also always takes place from the standpoint of some theory, so to for social criticism with respect to tradition. Social criticism necessarily focuses on particular traditions and does so from the standpoint of a tradition. In fact, the critical attitude toward tradition is itself a tradition — namely the scientific tradition — that dates back to the ancient Greeks of the 5th and 6th century B.C.E.

Popper’s theory of democracy also arguably contained conservative elements insofar as it required only a limited role for the average citizen in governing. As we saw above, the primary role of the public in Popper’s democracy is to render a verdict on the success or failure of a government’s policies. For Popper public policy is not to be created through the kind of inclusive public deliberation envisioned by advocates of radical or participatory democracy. Much less is it to be implemented by ordinary citizens. Popper summed up his view by quoting Pericles, the celebrated statesman of Athenian democracy in 5th-century B.C.E.: “’Even if only a few of us are capable of devising a policy or putting it into practice, all of us are capable of judging it’.” Popper added, “Please note that [this view] discounts the notion of rule by the people, and even of popular initiative. Both are replaced with the very different idea of judgement by the people” (Lessons of This Century, 72, Popper’s emphasis). This view in some ways mirrors traditional conservatives’ support for rule by “natural aristocrats,” as Burke called them, in a democratic society. Ideally, elected officials would be drawn from the class of educated gentlemen, who would be best fit to hold positions of leadership owing to their superior character, judgment and experience. However, in Popper’s system, good public policy in a democracy would result not so much from the superior wisdom or character of its leadership but rather from their commitment to the scientific method. As discussed above, this entailed implementing policy changes in a piecemeal fashion and testing them through the process of trial and error. Popper’s open society is technocratic rather than aristocratic.

3. References and Further Reading

The key texts for Popper’s political thought are The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) and The Poverty of Historicism (1944/45). Popper continued to write and speak about politics until his death in 1994, but his later work was mostly refinement of the ideas that he developed in those two seminal essays. Much of that refinement is contained in Conjectures and Refutations (1963), a collection of essays and addresses from the 1940s and 50s that includes in-depth discussions of public opinion, tradition and liberalism. These and other books and essay collections by Popper that include sustained engagement with political theory are listed below:

a. Primary Literature

- Popper, Karl. 1945/1966. The Open Society and Its Enemies, Vol. 1, Fifth Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Popper, Karl. 1945/1966. The Open Society and Its Enemies, Vol. I1, Fifth Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Popper, Karl.1957. The Poverty of Historicism. London: Routledge.

- A revised version of “The Poverty of Historicism,” first published in the journal Economica in three parts in 1944 and 1945.

- Popper, Karl. 1963/1989. Conjectures and Refutations. Fifth Edition. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Popper, Karl. 1976. Unended Quest. London: Open Court.

- Popper’s intellectual autobiography.

- Popper, Karl.1985. Popper Selections. David Miller (ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Contains excerpts from The Open Society and The Poverty of Historicism, as well as a few other essays on politics and history.

- Popper, Karl. 1994. In Search of a Better World. London: Routledge.

- Parts II and III contain, respectively, essays on the role of culture clash in the emergence of open societies and the responsibility of intellectuals.

- Popper, Karl. 1999. All Life Is Problem Solving. London: Routledge.

- Part II of this volume contains essays and speeches on history and politics, mostly from the 1980s and 90s.

- Popper, Karl. 2000. The Lessons of This Century. London: Routledge.

- A collection of interviews with Popper, dating from 1991 and 1993, on politics, plus two addresses from late1980s on democracy, freedom and intellectual responsibility.

b. Secondary Literature

- Bambrough, Renford. (ed.). 1967. Plato, Popper, and Politics: Some Contributions to a Modern Controversy. New York: Barnes and Noble

- Contains essays addressing Popper’s controversial interpretation of Plato.

- Corvi, Roberta. 1997. An Introduction to the Thought of Karl Popper. London: Routledge.

- Emphasizes connections between Popper’s epistemological, metaphysical and political works.

- Currie, Gregory, and Alan Musgrave (eds.). 1985. Popper and the Human Sciences. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Plublishers.

- Essays on Popper’s contribution to the philosophy of social science.

- Frederic, Raphael. 1999. Popper. New York: Routledge.

- This short monograph offers a lively, sympathetic but critical tour through Popper’s critique of historicism and utopian planning.

- Hacohen, Malachi Haim. 2000. Karl Popper: The Formative Years, 1902-1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- This definitive and exhaustive biography of the young Popper unveils the historical origins of his thought.

- Jarvie, Ian and Sandra Pralong (eds.). 1999. Popper’s Open Society after 50 Years. London: Routledge.

- A collection of essays exploring and critiquing key ideas of The Open Society and applying them to contemporary political problems.

- Magee, Brian. 1973. Popper. London: Fontana/Collins.

- A brief and accessible introduction to Popper’s philosophy.

- Notturno, Mark. 2000. Science and Open Society. New York: Central European University Press.

- Examines connections between Popper’s anti-inductivism and anti-positivism and his social and political values, including opposition to institutionalized science, intellectual authority and communism.

- Schilp, P.A. (ed.) 1974. The Philosophy of Karl Popper. 2 vols. La Salle, IL: Open Court.

- Essays by various authors that explore and critique his philosophy, including his political thought. Popper’s replies to the essays are included.

- Shearmur, Jeremey. 1995. The Political Thought of Karl Popper. London: Routledge.

- Argues that the logic of Popper’s own ideas should have made him more leery of state intervention and more receptive to classical liberalism.

- Stokes, Geoffrey. 1998. Popper: Philosophy, Politics and Scientific Method. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Argues that we need to consider Popper’s political values to understand the unity of his philosophy.

Author Information

William Gorton

Email: bill_gorton@msn.com

Alma College

U. S. A.

J. L. Austin was one of the more influential British philosophers of his time, due to his rigorous thought, extraordinary personality, and innovative philosophical method. According to John Searle, he was both passionately loved and hated by his contemporaries. Like Socrates, he seemed to destroy all philosophical orthodoxy without presenting an alternative, equally comforting, orthodoxy.

J. L. Austin was one of the more influential British philosophers of his time, due to his rigorous thought, extraordinary personality, and innovative philosophical method. According to John Searle, he was both passionately loved and hated by his contemporaries. Like Socrates, he seemed to destroy all philosophical orthodoxy without presenting an alternative, equally comforting, orthodoxy.

In two works, a paper in The Journal of Symbolic Logic in 1946 and the book Meaning and Necessity in 1947,

In two works, a paper in The Journal of Symbolic Logic in 1946 and the book Meaning and Necessity in 1947,