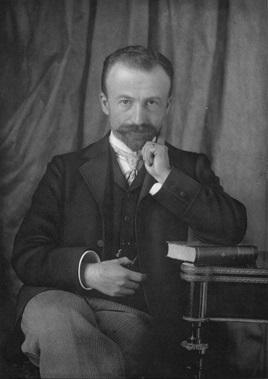

Edmund Husserl (1859—1938)

Although not the first to coin the term, it is uncontroversial to suggest that the German philosopher, Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), is the “father” of the philosophical movement known as phenomenology. Phenomenology can be roughly described as the sustained attempt to describe experiences (and the “things themselves”) without metaphysical and theoretical speculations. Husserl suggested that only by suspending or bracketing away the “natural attitude” could philosophy becomes its own distinctive and rigorous science, and he insisted that phenomenology is a science of consciousness rather than of empirical things. Indeed, in Husserl’s hands phenomenology began as a critique of both psychologism and naturalism. Naturalism is the thesis that everything belongs to the world of nature and can be studied by the methods appropriate to studying that world (that is, the methods of the hard sciences). Husserl argued that the study of consciousness must actually be very different from the study of nature. For him, phenomenology does not proceed from the collection of large amounts of data and to a general theory beyond the data itself, as in the scientific method of induction. Rather, it aims to look at particular examples without theoretical presuppositions (such as the phenomena of intentionality, of love, of two hands touching each other, and so forth), before then discerning what is essential and necessary to these experiences. Although all of the key, subsequent phenomenologists (Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Gadamer, Levinas, Derrida) have contested aspects of Husserl’s characterization of phenomenology, they have nonetheless been heavily indebted to him. As such, he is arguably one of the most important and influential philosophers of the twentieth century. The key features of his work, and his understanding of the phenomenological method, are considered in what follows.

Although not the first to coin the term, it is uncontroversial to suggest that the German philosopher, Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), is the “father” of the philosophical movement known as phenomenology. Phenomenology can be roughly described as the sustained attempt to describe experiences (and the “things themselves”) without metaphysical and theoretical speculations. Husserl suggested that only by suspending or bracketing away the “natural attitude” could philosophy becomes its own distinctive and rigorous science, and he insisted that phenomenology is a science of consciousness rather than of empirical things. Indeed, in Husserl’s hands phenomenology began as a critique of both psychologism and naturalism. Naturalism is the thesis that everything belongs to the world of nature and can be studied by the methods appropriate to studying that world (that is, the methods of the hard sciences). Husserl argued that the study of consciousness must actually be very different from the study of nature. For him, phenomenology does not proceed from the collection of large amounts of data and to a general theory beyond the data itself, as in the scientific method of induction. Rather, it aims to look at particular examples without theoretical presuppositions (such as the phenomena of intentionality, of love, of two hands touching each other, and so forth), before then discerning what is essential and necessary to these experiences. Although all of the key, subsequent phenomenologists (Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Gadamer, Levinas, Derrida) have contested aspects of Husserl’s characterization of phenomenology, they have nonetheless been heavily indebted to him. As such, he is arguably one of the most important and influential philosophers of the twentieth century. The key features of his work, and his understanding of the phenomenological method, are considered in what follows.

Table of Contents

- Biography

- How to Interpret Husserl’s Texts

- On the Concept of Number (Übert den Begriff der Zahl, 1887)

- Logical Investigations (Logische Untersuchungen, 1900-01)

- Ideas I (Ideen I, 1913)

- Ideas II (Ideen II)

- References and Further Reading

1. Biography

Edmund Husserl was born April 8, 1859, into a Jewish family in the town of Prossnitz in Moravia, then a part of the Austrian Empire. Although there was a Jewish technical school in the town, Edmund’s father, a clothing merchant, had the means and the inclination to send the boy away to Vienna at the age of 10 to begin his German classical education in the Realgymnasium of the capital. A year later, in 1870, Edmund transferred to the Staatsgymnasium in Olmütz, closer to home. He was remembered there as a mediocre student who nevertheless loved mathematics and science, “of blond and pale complexion, but of good appetite.” He graduated in 1876 and went to Leipzig for university studies.

At Leipzig Husserl studied mathematics, physics, and philosophy, and he was particularly intrigued with astronomy and optics. After two years he went to Berlin in 1878 for further studies in mathematics. He completed that work in Vienna, 1881-83, and received the doctorate with a dissertation on the theory of the calculus of variations. He was 24. Husserl briefly held an academic post in Berlin, then returned again to Vienna in 1884 and was able to attend Franz Brentano’s lectures in philosophy.

In 1886 he went to Halle, where he studied psychology and wrote his Habilitationsschrift on the concept of number. He also was baptized. The next year he became Privatdozent at Halle and married a woman from the Prossnitz Jewish community, Malvine Charlotte Steinschneider, who was baptized before the wedding. The couple had three children. They remained at Halle until 1901, and Husserl wrote his important early books there. The Habilitationsschrift was reworked into the first part of Philosophie der Arithmetik, published in 1891. The two volumes of Logische Untersuchungen came out in 1900 and 1901.

In 1901 Husserl joined the faculty at Göttingen, where he taught for 16 years and where he worked out the definitive formulations of his phenomenology that are presented in Ideen zu einer reinen Ph‰nomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie (Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy). The first volume of Ideen appeared in the first volume of Husserl’s Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung in 1913. Then the world war disrupted the circle of Husserl’s younger colleagues, and Wolfgang Husserl, his son, died at Verdun. Husserl observed a year of mourning and kept silence professionally during that time.

However Husserl accepted appointment in 1916 to a professorship at Freiburg im Breisgau, a position from which he would retire in 1928. At Freiburg Husserl continued to work on manuscripts that would be published after his death as volumes two and three of the Ideen, as well as on many other projects. His retirement from teaching in 1928 did not slow the pace of his phenomenological research. But his last years were saddened by the escalation of National Socialism’s racist policies against Jews. He died of pleurisy in 1938, on Good Friday, reportedly as a Christian.

Most commentators, therefore, recognize three periods in Husserl’s career: the work at Halle, Göttingen, and Freiburg, respectively. Some argue that one or another of these periods ought to be taken as definitive and used as the interpretive key to unlock the others. But such an approach highlights disjunctions in Husserl’s thought while neglecting the significant continuities. Important strands of Husserl’s philosophy have their beginning long before his academic career commenced.

The community into which Husserl was born, Prossnitz, was a center of talmudic learning whose yeshiva had produced or welcomed a number of famous rabbis during the two centuries before Husserl’s birth. This scholarly activity was supported by the industries of textile and clothing manufacture, through which Prossnitz’s Jews had enhanced the prosperity of the region. Jews and Germans were minorities in the town and appear to have comprised its middle class. Their interests were naturally allied against those of the Slavic majority. (For example, the census of 1900 counted 1,680 Jews among the town’s 24,000 inhabitants, according to The Jewish Encyclopedia.) In the ethnically diverse town, several dialects were spoken, and the language of the Husserl home probably was Yiddish.

The Jewish community of Prossnitz had established a technical school in 1843, and it became a public school for all the town’s children in 1869–one year before young Edmund Husserl was sent off to Vienna’s Realgymnasium. 1868 was also a year when civic authorities called for reform of Jewish education at all levels throughout Moravia. These developments reflect a movement toward modernization and integration after centuries of enforced segregation and legal restriction of Jewish life.

Prossnitz was the second-largest Jewish community in Moravia, with 328 families. Exactly 328 families; it could have no more, because of the quota established by the Bohemian Familianten Gesetz in 1787. The Jewish population was controlled through marriage licenses. Civil law set specific economic, age, and educational requirements; but in addition, the license could be granted only after a death freed up one of the allotted 328 slots. In effect, only first sons could hope to marry. Others had to emigrate if they wanted to have families of their own. This population-control policy was enforced until 1849, ten years before Edmund Husserl’s birth. The requirement that Jews obtain special marriage licenses remained in effect until late in 1859, some months after Edmund’s birth.

But Edmund Husserl’s childhood was spent during an era of liberalization for Prossnitz’s Jews. He received an elite secular education and probably made his father quite proud. At that period, gymnasia provided separate religious instruction for Christian boys and Jewish boys. Edmund’s Jewish education would have continued in that context and in the language of secular culture, High German. He could hear and read the Bible in that modern language as well, for in the nineteenth century a wave of new translations into the language of German culture was spawned by Moses Mendelssohn’s groundbreaking work. (Mendelssohn’s 1783 translation into High German was printed in Hebrew characters, phonetically, to make it easy to read.) Some of these editions were lavishly illustrated for display in bourgeois homes like Edmund’s, and most took into account the findings of recent historical and philological science. But during Edmund’s childhood, translating the Hebrew Bible was still a controversial issue. Some educational leaders in the Jewish community warned that it would undermine Hebrew learning among the young. Hebrew learning was evidently not prized by a father who would send his son to the capital to study Greek and Latin at the age when boys traditionally were sent down the street to learn Hebrew and Torah. To complicate the picture, in 1870 when Edmund was eleven, a new rabbi came to serve the Prossnitz community.

One may surmise, then, that Edmund Husserl came by his knowledge of the Bible through his classical secular education, not his religious tradition. It was of a piece with the German cultural heritage for him. It was a source of literary allusions, and in later life he could compare himself to Moses and to Sisyphus with equal ease.

Literary allusions, along with fragments of correspondence, are all that remain to us for the reconstruction of what Husserl may have felt about himself and his work. There is no autobiography per se. But there are retrospective texts. One of the most illuminating is the brief introduction that Husserl prepared for the 1931 publication in English of the first book of Ideen, originally brought out in 1913.

Now in his seventies, Husserl complains that most readers have misunderstood his life’s work. When he undertakes to reformulate what phenomenology is and what he has accomplished, however, he writes from a vantage point that he did not have some two decades earlier. Husserl becomes, in effect, a critic and interpreter of his own work, which he describes with a sustained metaphor. He portrays himself as an explorer who has opened the way into new territory so that others may conquer, map, and farm it. Of himself, Husserl writes:

“(H)e who for decades did not speculate about a new Atlantis but instead actually journeyed in the trackless wilderness of a new continent and undertook the virgin cultivation of some of its areas will not allow himself to be deterred in any way by the rejection of geographers who judge his reports according to their habitual ways of experiencing and thinking and thereby excuse themselves from the pain of undertaking travels in the new land” (422)

Here is another example of this characterization:

I can see spread out before me the endlessly open plains of true philosophy, the ‘promised land’, though its thorough cultivation will come after me” (429)

By means of this spatial, geographical metaphor of crossing over into the “new land,” Husserl conveys something of the adventure and pioneer courage that should accompany phenomenological work. This science is related to “a new field of experience, exclusively its own, the field of ‘transcendental subjectivity’,” and it offers “a method of access to the transcendental-phenomenological sphere” (408). Husserl is the “first explorer” (419) of this marvelous place.

2. How to Interpret Husserl’s Texts

Husserl had already employed the spatial metaphor in the 1913 text, although without explicit reference to himself as explorer. In chapter I-1 of Ideen I he had distinguished states of affairs (Sachverhaltnis) from essences (Wesen) by assigning them to two “spheres”: the factual or material, and the formal or eidetic, respectively. These spheres are connected only by the mind’s ability to pass between them as easily as moving around within either of them; they do not connect on their own, as it were. That is, no causality obtains between them. “Movement between” and “movement within” are of course further elaborations upon the spatial metaphor, and serve to designate the ability of consciousness to flow along, concentrate itself, linger, combine, focus, or disperse as it will. Such acts of consciousness belong to these spheres. They are worldly. They are “psychological.”

Husserl’s task is to get from those spheres into another “field” that is quite unlike them. It will be the sphere of absolute consciousness, consciousness when it isn’t going anywhere. As the title of chapter II-3 puts it, this will be “The Region of Pure Consciousness.” You can’t “go there” with consciousness; instead you have to let the worldly go away and then inhabit what’s left. This is the import of the infamous fantasy that opens paragraph 33: “(W)as kann als Sein noch setzbar sein, wenn das Weltall, das All der Realit‰t eingeklammert bleibt?” (In Kersten’s paraphrase: “What can remain, if the whole world, including ourselves with all our cogitare, is excluded?” [63])

Now, it’s quite curious that Husserl should choose the spatial metaphor to introduce and induce his phenomenological reduction. This metaphor invites confusion for anyone familiar with Descartes– who after all named spatial extension as the substantial attribute of material being. None of Husserl’s “spheres” is literally extended, in the Cartesian sense; yet all are coextensive (coincident) with material being–inasmuch as there’s literally nowhere else besides the material universe where they could be. Why then should Husserl choose such an incongruous and counterproductive metaphor? A different metaphor (such as “fabric” or “organism,” for example) could have conveyed the notions of coherence, separation, and access that Husserl intended. What is distinctive about the spatial metaphor, however, is that it connotes exploration and conquest. If transcendental consciousness is a promised land, then you need a Moses to lead you toward it. You need Husserl. When Husserl remarks, in the 1931 Introduction, that he can look down across that land that he has discovered, but that others will enter, this is a literary allusion to the figure of Moses, who led his people to Canaan, “the promised land,” but did not lead them into it (Deuteronomy 34).

If these allusions from 1931 can be taken as a thumbnail self- portrait, still one must remember that it was sketched during Husserl’s retirement. But Husserl’s thought grew and changed throughout his long career. In his maturity, the philosopher joined his readers in producing commentary upon his youthful work. The three phases of Husserl’s career–Halle, Göttingen, and Freiburg–invite facile divisions, and decisive turning points have been suggested within each of those periods. (The survival of nearly 45,000 pages of stenographic notes from Husserl’s teaching and his private researches has fueled disputes about when he might have had the first glimmer of a thought that led to a lecture comment that led to a paragraph that found its way into a book published long after the man’s papers and ashes were shelved in Louvain!)

Husserl himself insisted that the threads of continuity throughout the evolution of his thought were more significant than any false starts that later had to be repudiated. It seems well to grant him this point. Yet on two issues one must take seriously the critical discussion arising from disjunctions in Husserl’s thought: (a) the question whether to characterize Husserl as realist or idealist, and (b) the question of which stage of Husserl’s evolution–if any–should be taken as the definitive version through which all other versions are to be read. Husserl himself, writing as his own critic later in life, took a position on each of those issues. On (a), he insisted that he was and always had meant to be a transcendental idealist. On (b), he claimed competence to correct the insights of 1887, 1900, and 1913 with the insights of the 1920’s and 1930’s. Thus the mature Husserl would wish to erase the impression that his early work resolved the realism-idealism conundrum in favor of realism, and that it did so in fidelity to an insight already expressed in his earliest work on number.

Various punctuations of Husserl’s career by time, place, and predominant question have been suggested by commentators (for example, Kockelmans 1967: 17-23; Ricoeur 1967: 3-12; Biemel 1970; and Bell 1990). Husserl’s phenomenology developed gradually, but there were several relatively sudden turns and several stalls. Two examples suffice to illustrate. While at Halle shortly after the publication of Philosophie der Arithmetik, Husserl distanced himself from his recent efforts to establish mathematical and logical principles upon the psychological operations of the mind—a project that he later termed “psychologism.” Many commentators have characterized this as an abrupt turn made in response to Frege’s effective criticism of Philosophie der Arithmetik. However Mohanty (1982: 13), who examines the Frege-Husserl correspondence along with other documentary evidence, concludes to the contrary, that:

the seeds of development of Husserl’s philosophy from the Philosophie der Arithmetik to the Prolegomena [i.e., the first volume of the Logische Untersuchungen, 1900] were immanent to his own thinking, so that the hypothesis of a traumatic effect of Frege’s 1894 review of his book and a consequent reversal of his mode of thinking is not only uncalled for but also unsubstantiated by the available evidence.

Mohanty, then, provides ample warrant for a reading of Husserl that pursues threads of continuity between his early mathematical work and the breakthrough to phenomenology while at Halle.

In a second example of a supposed disjuncture in Husserl’s development, there has been discussion of whether he changed his stance from realism to idealism between Göttingen and Freiburg. On the one hand, Eugen Fink (1933) and many others see a consistent evolution of transcendental idealism from the work published in Ideen I onward. They tend either to dismiss the earlier works as if they were merely youthful failures, or forcibly to harmonize the realist passages with Husserl’s later positions. Husserl himself endorsed such a reading. On the other hand, those who studied with Husserl at Göttingen insist that his work at that time had validity and integrity in its own right. His former student Edith Stein (1932: 44-45) remarks that Husserl’s disciples were surprised at the idealistic passages in Ideen, and she calls Fink a latecomer to Husserl’s phenomenology. One of Stein’s contemporaries among Husserl students, Roman Ingarden (1962: 159), says that:

the idealistic tendencies apparent in volume I of the Ideen had been opposed by his disciples when the work was being studied during the seminars at Göttingen and . . . his disciples pointed out many passages in the Ideen which seemed to contain direct arguments against his idealism.

Subsequently Ingarden presented arguments, based on both the text of Logische Untersuchungen and his conversations with Husserl, in support of the view that Husserl originally espoused a realist standpoint but later abandoned it (Ingarden 1975: 4-8). Further discussion of the issue is to be found in Kockelmans (1967: 418-449) and in Van de Pitte (1981: 36-42)–who suggests that the discrepancy will vanish if one reads Husserl’s idealism as an epistemological or methodological approach to a metaphysically real world.

For his own part, Husserl (1931: 418-9) claimed that his transcendental idealism had advanced altogether beyond ordinary idealism, beyond realism, and beyond the very distinction between them. He denied that he ever had held a realist position:

. . . I still consider, as I did before, every form of the usual philosophical realism nonsensical in principle, no less so than that idealism which it sets itself up against in its arguments and which it “refutes.” [Phenomenological reduction] is a piece of pure self- reflection, exhibiting the most original evident facts; moreover, if it brings into view in them the outlines of idealism . .. it is still anything but a party to the usual debates bewteen idealism and realism. . . .

Husserl argued that transcendental-phenomenological idealism did not deny the actual existence of the real world, but sought instead to clarify the sense of this world (which everyone accepts) as actually existing.

Thus Husserl joins the company of those who read his work “backwards,” from the standpoint of Freiburg, interpreting the earliest work in light of the transcendental idealism of the latest. This reading grants no validity to the earlier work in its own right. It sets Husserl against Kant, and phenomenology’s thoroughgoing idealism against Kantian critical idealism. Fink, in his detailed response to neo- Kantians’ readings of Husserl’s phenomenology (1932), scolds them for even addressing arguments made in Husserl’s 1900-1 and 1913 publications–for Fink contends that those positions now must be assimilated to Husserl’s later formulations. The extreme hermeneutical implications of this stance come clear in Fink’s delineation of the threefold paradox entailed in reading Husserl’s phenomenology: (1) It is inevitably misunderstood if the reader has not first cultivated the transcendental attitude; yet that attitude arises from the reading. (2) The words necessarily miss their meaning, and fail to refer effectively to the pre-worldly realm of transcendental subjectivity, since all available words are worldly. (3) Phenomenology goes to a realm beyond logic, individuation, and determination, which ordinarily structure understanding. In this extreme form, then, the Freiburg reading of Husserl’s work is a locked door for the newcomer who is trying to get acquainted with Husserl’s phenomenology.

Fortunately, there are other hermeneutical options. A second group of commentators read Husserl “forward” from his intellectual beginnings at Vienna and Halle. The early work in mathematics and logic continues to attract the interest of Analytic philosophers. They are among those who argue that Husserl’s concern with numbers and logical reasoning, stimulated by the Kantian challenge, fructified in the prescription of eidetic and, eventually, phenomenological reductions.

Besides reading Husserl from Halle “forward” or from Freiburg “backward,” there is yet a third option. One may base one’s reading upon the Göttingen period and upon questions involving the genesis of the Ideen, as the keystone in the arch of Husserl’s development. This is the stance suggested by Ingarden, who considered Husserl’s later transcendentalism a big mistake, and by Stein, whose own subsequent works unfold the implications of the realism and personalism embraced by Husserl at that period. On this view the world, lost by Kant, is won back for science.

The problems of oneness and unity occupied Husserl throughout all the phases of his philosophical development: his earliest work on number and logic, his pre-war realist descriptive phenomenology, and his idealist transcendental phenomenology. His philosophy in some respects parallels the emergence of modern psychology, with whose tenets it should not be confused. The following are his major works.

3. On the Concept of Number (Übert den Begriff der Zahl, 1887)

Husserl’s Habilitationsschrift is subtitled “psychological analyses,” and it addresses the question how we recognize manyness within a group. Husserl remarks that the common definition of number–that number is a multiplicity of units–leaves two key questions unanswered: “What is ‘multiplicity’? And what is ‘unity’?” It is the former question, multiplicity, that occupies his attention throughout the essay. However the latter question, unity, haunts the discussion and refuses to be ignored.

Husserl locates the origin of multiplicity in the activity of combining, which he takes to be a psychological process. After much consideration he identifies this activity as synthesis, or the gathering of items into a set. He notices then that synthetic unities are of two kinds. Either the relationship through which the multiple items belong to the one set is a content of the mental representation of those items (right in there alongside them as another item that can be attended to and counted), or it is not there. In the former case, the unity is physical. Otherwise it is psychical, stemming from the unifying mental act that sets the contents into the relationship.

Having made that distinction between natural or physical unity, and arbitrary or imposed unity, Husserl then goes on to contrast these varieties of synthetic oneness with something else entirely: unsynthesized unity. His example is a rose, whose so-called parts are continuous and come apart only for the examining mind.

“In order to note the uniting relations in such a whole, analysis is necessary. If, for example, we are dealing with the representational whole which we call ‘a rose,’ we get at its various parts successively, by means of analysis: the leaves, the stem…. Each part is thrown into relief by a distinct act of noticing, and is steadily held together with those parts already segregated” (114).

Ironically, Husserl has struck gold while mining coal, and doesn’t quite recognize what he’s got hold of. His description of nonsynthesized unity comes almost as a byproduct of his attempt to differentiate physical or real collective combination from psychic combination. He writes:

“… these combining relations present themselves as, so to speak, a certain ‘more,’ in contrast to the mere totality, which appears merely to seize upon its parts, but not really to unite them [because they’re already united, independently of the mind!]…. In the totality there is a lack of any intuitive unification, as that sort of unification so clearly manifests itself in the metaphysical or continuous whole” (114).

Husserl has succeeded in distinguishing between natural and artificially synthesized wholes, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, those totalities that are known as having been accomplished neither by natural aggregation nor by mental combination. The unity of such wholes is known to be real, even though it admits of subsequent mental analysis or physical dissection.

Again ironically, in his concluding discussion of “number” Husserl neglects to notice the number one even as he employs it to illustrate how combination works. Substituting the term “and” for the term “collective combination,” Husserl remarks:

“(T)otality or multiplicity in abstracto is nothing other than ‘something or other’, and ‘something or other’, and ‘something or other’, etc.; or, more briefly, one thing, and one thing, and one thing, etc. Thus we see that the concept of the multiplicity contains, besides the concept of collective combination, only the concept something. Now this most general of all concepts is, as to its origin and content, easily analyzed” (116).

Husserl terms the concept something the most general concept. It stands for any object–real or unreal, physical or psychical–upon which we reflect. Thus he says that multiplicity as a concept arises out of the indetermination of the et-cetera that allows the series of “one and one and one and …” to go however far you like.

Yet an objection must be registered concerning what Husserl has found but not noticed. Multiplicity is but relatively undetermined; ultimately, multiplicity is in fact determined, or reined in, by one itself. This happens at three points. (a) One is the starting point of the counting series. Every number except the first number is a multiplicity; therefore the set of natural numbers is greater (by one!) than the set of multiplicities. (b) One determines the unit of counting. Only one something at a time gets counted. The and‘s must be put in between one‘s. (c) Although the series can stop anywhere, nevertheless it has to stop at one single place, not at several places. Every number is one distinct number.

Husserl, however, tries to produce the concept number by suppressing what he has taken to be the absolute indetermination of the something-series. This is how he gets determinate multiplicity, which he equates with number. In other words, the and‘s are the main ingredient for making numbers Husserl-style. This is incorrect, of course, but it is incorrect in an interesting way. For example, to make the number five, you would need four and‘s. To come up with those four and‘s, you would have to count them out; but before you could count to four, you would need three and‘s with which to make that four. But… there’s a regression back to one. The number five is four and’s, and five one’s.

The maddening difficulty of focusing upon combination eventually will have a happy outcome, which Husserl did not see in 1887. The truly interesting problem is one, the prime ingredient in numbers and the determiner whose own determination was to become Husserl’s guiding quest.

4. Logical Investigations (Logische Untersuchungen, 1900-01)

With the turn of the century, Husserl’s attention turned from and to one; that is, away from the mental activity of combining, and toward that which is reliably there to be combined. He wanted to show that mental activity is not the source of the latter. Chapter 8 of LU I exposes and refutes the three premises or “prejudices” of psychologism. In short, “psychologism” for Husserl is the error of collapsing the normative or regulative discipline of logic down onto the merely descriptive discipline of psychology. It would make mental operations (such as combination) the source of their own regulation. The “should” of logic, that utter necessity inhering in logical inference, would become no more than the “is” or facticity of our customary thinking processes, empirically described.

Husserl’s formulation and refutation of the three psychologistic premises is wickedly clever, but cannot be treated in detail here. (See # 43-49 of LU I.) One example must suffice. Psychologism, Husserl charges, would place logical inferences on the same plane with mental operations (# 44), and this would make even mathematics into a branch of psychology (# 45). Indeed, math and logic do have structures that are isomorphic to those of mental operations, such as combination and distinction. But given that similarity, how then would one distinguish the regulation of any of these processes from the description of it? Under psychologism, there’s no way. But Husserl makes the distinction in a way that also shows how regulation (that is, the laws of logic) comes from elsewhere than the plane of mental activity.

And he does this by virtue of one. In # 46 Husserl agrees with his opponents that arithmetical operations occur in patterns that refer back to mental acts for their origin and also for their meaning. However, there’s a difference between them as well. Mental acts transpire in time: they begin and end, and they can be repeated and individually counted. Numbers, in contrast, are timeless. While they can be represented in mental acts, this representation is not a fresh production of the number but rather an instantiation of its form. There is only one five. Any time we count five things, it isn’t a production of a new five but merely a deja vu for the same old five, eternal five. We can’t count numbers themselves, for there’s only one of each. (A similar argument is made in #22 of Ideas I.)

The same goes for logic, Husserl says. Concepts comprising the laws of pure logic can have no empirical range. Their range or sphere is ideal singulars, not mental generalizations from multiple instantiations. The operators of logic are other than those mental acts that happen to share the same names: “and,” “not,” “is,” “or,” “implies,” “may,” “must,” “should.” Psychologically, there can be many factual acts of combining, negating, etc. Logically, there is only one “and,” one “not,” etc. Husserl concedes here, as he did for arithmetic, that the logical operators take their origin and meaning from the mental acts. This accounts for the equivocal character of logical terms, which refer both to ideal singulars, and to mental states and acts. But if you fail to notice this equivocation, you become ensnared in psychologism, losing the possibility of pure logic and unified science.

The danger of equivocation extends over judgments as well. On the one hand, we can count multiple apperceptive events of affirmation, occurring psychologically, which proceed in time, begin and end, and recur as often as we like, in happenings that can be distinguished one from another. On the other hand, the judgment thus reached remains the same throughout each act accessing it. It seems to persist and to be called back for encore appearances; it seems even to have pre-existed its first appearance to me (# 47). In this latter sense, the judgment is not the same as the mental act that reaches it. Moreover, the truth of the judgment is neither equivalent to nor dependent upon the psychological experience of clear evidence that accompanies the mental act embracing it. Husserl easily shows this by recalling that in both logic and arithmetic, there are truths that have never been entertained in any human consciousness, and indeed could never be humanly conceived (# 50). (Cases of truth without the possibility of psychological evidence would include the computation of very large numbers, and decisions about membership in sets that are uncountably large. The arithmetical and logical operations connected with such determinations could never be “done” by a human mind or a computer. Their truth cannot be “factual.”)

The number one, then, has become Husserl’s touchstone for discriminating between psychological processes and logical laws. It is his reality detector. What is psychological (or empirical) comes on in discrete individual instances–ones–and you can examine their edges. What is logical (or ideal) comes on as a seamless oceanic unity without temporal edges, reliably persisting even when not attended to. Husserl’s sensitivity to the modes of unity, first expressed in the Habilitationsschrift and developed in LU, provides the launching pad for transcendental phenomenology.

5. Ideas I (Ideen I, 1913)

What launches transcendental phenomenology is the recognition that those modes of unity correlate with each other and with a third mode of unity, in ways that are tantalizingly asymmetrical. These three onenesses are: the factual unity of things and states of affairs, the eidetic unity of essences, and the living unity of consciousness as it flows along in a stream of experiences. Each has, and exhibits, its own distinctive kind of identity and persistence. Factual and essential unities give objects to the straightforward regard of consciousness, entering it as items of experience, each in its distinctive way; but consciousness can also deflect its regard back onto these enterings and discover its own unity, which is unlike either of theirs.

The possibility of this complex correlation is provided by the “principle of principles”: that intuitions come on to us with distinctive boundary-conditions that we can accept as sources insuring the correctness of our knowledge of them. Or in Husserl’s formulation:

“… that every originary presentive intuition is a legitimizing source of cognition, that everything originarily (so to speak, in its “personal” actuality) offered to us in ‘intuition’ is to be accepted simply as what it is presented as being, but also only within the limits in which it is presented there” (44).

The different kinds of unities have different kinds of edges, and these give away what kind of a unity each of them is going to be. But it’s easy to miss the differences. That happens in the natural attitude, Husserl says, when all the objects of consciousness are taken as if they were factual items. Husserl complains that even his Logische Untersuchungen have been misunderstood as advocating just this error of “Platonic realism,” by those who read into his use of the term “object” the implication that, through a perverse hypostatization, every thought turns into a thing (# 22). On the contrary, he says, the eidetic reduction, operative already in LU, empowers him to differentiate between how essences appear, and how cases appear.

Now with Ideen I, this distinction is sketched in beautiful detail. You can tell when the object occupying your consciousness is a physical thing, because things don’t give themselves to you all at once. What you get instead is a perspective inviting you to move around to the other side to perceive some more of the thing. All the while the thing keeps its unity to itself, as the reference point of all the angles it gives to you, and out of which you must reproduce or copy or simulate the unified thing as you conceive it. But in conceiving, you don’t have to put an “and” between two separate perceptions, the north face of a building and the south face, in order to yield the perception of the building as if it were a sum. These different views are given to you as continuous, as views of one thing.

Husserl terms this “shading off” or adumbration. (The notion of off-shading is reminiscent of a multiple-exposure photograph that captures successive phases of a movement in a single frame. Such photos were being seen for the first time at the turn of the century. Husserl also mentions new media such as the stereoscope and the cinema.) In contrast, essences give themselves to you all at once. Their boundaries are not sides, but rather laws entailing the characteristic necessities and possibilities of kinds of things (more about which below). The unity of any particular essence coheres within that determinate outermost boundary which free imaginative variations of possible cases must not exceed if they are to remain cases of this particular kind. Essential unity is centripetal, so to speak.

Then are those other unities–the ones presenting themselves as extended or factual–to be termed centrifugal, inasmuch as each spins off appearances in all directions from an inaccessible center? No, for their off-shading appears contextualized, as a foreground; and even as we focus upon the foreground it pulls its background into readiness for perception as soon as attention may shift to it. Every one is surrounded by a halo of and‘s, and beyond that are other somethings, seemingly without end. Whatever is extended is inexorably connected to whatever else is extended. (This last formulation, by the way, is an instance of an eidetic law. But the shift of attention that brings this essential rule into view is an eidetic reduction, and it wrenches us away from our naive attention to instances of things naturally appearing, under consideration here.) Every perception “motivates” another, stretching on toward expanding horizons.

The shift to the transcendental attitude–that is, the phenomenological or transcendental reduction–brings to Husserl’s notice a third kind of unity, which discloses the off-shading of things in a startling new way. We notice now that what is adumbrated is spatial, but the adumbration itself is not spatial. It arises in consciousness. “Abschattung ist Erlebnis” (95), while what is adumbrated, das Abgeschattete, has to be something spatial. The off-shading of things is at the same time the streaming of conscious life. Peculiarly, the giving off of partial perceptibilities (by the thing) coincides with the taking up of partial perceptions (by streaming consciousness). Which one is doing the shading? Agency cannot be imputed absolutely to either side.

But on the “side” of consciousness, as it were, we now recognize that we are dealing with more than a progression of life-bites strung together in series with and‘s. The stream of conscious life is not a sum or aggregate; nor is it a generalization. That is, it exhibits a unity unlike either the sachverhaltig unity of a factual case or the eidetisch unity of an essence. Husserl must account for that unity, which he calls an ego, Ich.

Moreover, and of paramount significance, with the benefit of the transcendental reduction it can now be told that these three kinds of unities themselves are not connected merely in series, with and‘s combining them, as if they were three discrete somethings. Their relationship is vastly more subtle. In order to understand it, through reduction we try to isolate unity from what accounts for unity. (We are not looking for something “prior to” unity — such as some “cause” of unity –, because we can’t have priority without having the number one, and oneness is just what is in question.)

Isolating oneness from the live experience-stream means removing the individual subject (you or me or Napoleon or whomever) from consideration. What is left, says Husserl, is transcendental subjectivity, “the pure act-process with its own essence” (“das reine Akterlebnis mit seinem eigenen Wesen“). (Paradoxically, we can see, right here in this formulation, that the reduction has not at all done away with essence, with states of affairs, or even with identity. We still have Eigenheit and Wesen, set in relation within a sentence. But these are now supposedly purified.) Husserl likens this de-individualized ego to a ray (# 92) or glance (# 101). Characteristically (or essentially) it has two poles or directions: the noematic and the noetic (from Greek terms noema and noesis, indicating what is thought and the act of thinking, respectively).

Husserl’s discussion of “noetic-noematic structures” fails in its attempt to show how the ego reaches and secures both the unity of the known object, and the unity of the knowing subject. But it fails in a spectacular starburst of insight. Husserl notices that the mental stream has its own distinctive kind of adumbrations or continuities, which are more complex than those discussed above, the relatively simple off-shaded appearings of spatial objects in perception. Beyond that simple sort of off-shading, consciousness can also turn back on itself and reflect upon its own intending acts, or on any component thereof. The stream meanders among spatial objects, but can also at whim objectify aspects of its own acts of intending, and consider them. This yields a thick layering of possible objects (# 97). For example, here are some noemata that might enter the live experience stream: pencils … writing … German verbs … the frustration of strong verbs … Ulrike … memories in general … the unreliability of memory … components of perceptions … the advisability of analyzing perceptions into their components … the smell of popcorn wafting into the study … the effort to resist distractions … and so forth.

Some of these arise directly from things, while others arise as objectifications of what was inherent a moment ago in the very act of knowing, the noesis. How can we tell the difference? Husserl answers that you can tell when the ego-beam has penetrated through to the bottom of the stack of noemata, so to speak, and has gotten ahold of a thing itself, because at that point, all the aspects of the thing are known immanently–really–in the act of perceiving as being contained in the sense of the thing (# 98). For example, you know popcorn itself when you are perceiving the taste of butter and salt. (You do not know popcorn when you read this sentence; instead, you are reflecting on what it is to know popcorn, and popcorn’s qualities are not given immanently within your object. But then while tasting popcorn, saltiness was given immanently but not objectified.)

Husserl rightly points out that we are able to slide up and down the pole of the ego-beam at will, moving now toward the thing, now away from it to consider the act of knowing and its modalities. For example, noematically I can consider a certain cat who probably exists, but then I can turn back noetically to assess the degree of certitude that characterizes my consideration of that selfsame cat as existing (# 105). Now if we were to slide down to the point where all modalities are behind us on the noetic side of the pole, and if there we were to face the object, we would get the pure sense of the object in which its unity is given.

In # 102 Husserl claims that this can happen, and that we can indeed slide far enough toward the object that the unity of the noema will be known as not having been imposed by the act of knowing. At that point, all of its qualities supposedly will be given immanently, really, contained in the perception rather than in the secondary conscious act that may grasp it a split-second later. Its sense will have been captured as something known with certainty to comprise its qualities, without the interference of a synthetic conscious act. (If this worked, it would effectively ensure the objectivity of knowledge, and would win the day for realism against idealism.) Husserl writes:

“The noematic objects … are unities transcendent to, but evidentially intended to in, the mental process. But if that is the case, then characteristics, which arise in [those unities] for consciousness and which are seized upon as their properties in focusing the regard on them, cannot possibly be regarded as really inherent moments of the mental process” (248-249).

Rather, they inhere in the object’s sense, and subsequently are lifted out for analysis in the mental process.

The ambitiousness of this claim is matched by that of another, which has to do with the opposite end of the ego-pole. In # 108 Husserl says that we can also shinny far enough up the ego-pole that we can capture the affirming noesis in its purity. All the modalities will have been loaded over onto the side of the noema, and the no_sis will be a believing affirmation, pure and simple: an unqualified yes. Thus Husserl insists that there is a crucial difference between (a) being validly negated and (b) not-being. For example, he would distinguish (a) denying correctly that my spayed cat has a kitten, from (b) affirming that the kitten of my spayed cat is a non-entity. With (a), the negativity inheres in the noesis, which has not yet been purified of all modality; but with (b), the noesis would be pure affirmation (# 104).

How correct is Husserl’s argument? We must grant that whatever makes this particular kitten impossible inheres elsewhere than in my knowing about it, for my denying something can’t make it go away. Furthermore, there’s nothing to prevent my forcing myself to think positively the thought of the kitten that my cat never had. Such a noetic posture is at least conceivable. However, its mere possibility is not enough to accomplish Husserl’s purpose. Husserl needs to show that this pure affirming belief really is done, somewhere somehow, in the toughest case, the case of an intrinsically impossible entity such as the kitten of a spayed cat. (That is, has anyone succeeded in recapturing that magic moment of purely affirming noesis with regard to an intrinsically impossible object? And if so, how would one go about certifying the accomplishment?)

Unfortunately, neither end of the ego-ray connects as Husserl had hoped. At the noetic pole, the purely affirming ego eludes the grasp of consciousness; so does the pure sense of the thing itself, at the noematic pole. These terms may remain as ideal asymptotes toward which the ego-ray continually points while continually falling short. The successful recovery of the connection between knowing and reality awaits another strategy, to be mounted by Husserl in the posthumously published second volume of Ideen.

6. Ideas II (Ideen II)

The second volume of Husserl’s Ideen (publication withheld until 1952) is the work of many hands. Husserl was dissatisfied with it and did not publish it. The first draft was written very rapidly in 1912, immediately after the manuscript of the first volume was completed. Husserl added material in 1915, and turned it over for editing to his assistant Edith Stein, who had come with him to Freiburg from Gottingen. Stein transcribed the work from Husserl’s shorthand in 1916. He gave her further material, and in 1918 she produced a collation arranged and titled as at present: the constitution of material nature, of animal nature, and of the cultural world. But Husserl’s phenomenology was evolving, and the manuscript did not suit him. Another assistant, Ludwig Landgrebe, worked on it 1923-25, and Husserl himself edited it in again 1928. It finally came out posthumously.

If the pursuit of unity had guided Husserl like a north star from his earliest writing on through the discovery and first articulation of phenomenology, then in Ideen II that star becomes obscured by “light pollution” from numerous more recent and competing insights. Without access to the manuscripts, it is impossible to know with precision how that came about. In portions of the text as we have it, the concern with unity remains a significant factor.

However, other portions seem to go against the grain of key insights from the first volume and the earlier works. For example, in LU and Ideen I, the material sphere had comprised states of affairs; that is, facts or cases such as could be expressed in logical propositions. There were indeed “things” in there, such as roses, yet the emphasis was upon the factual scenarios into which these things figured. By contrast, in Ideen II “material nature” is populated with substantial items, and the fact they are embedded in circumstances has to be additionally stipulated, almost as an afterthought (# 15c). By the same token, in the earlier work the eidetic sphere had comprised the forms of logical propositions and the rules of inference. While there were indeed “essences” entailed there, nevertheless the emphasis fell upon the lawful patterns of thinking about being. By contrast, in Ideen II “animal nature” is populated by psychic items whose unity is analogous to that of physical things yet whose active engagement with the latter can hardly be explained.

This shift matters, because judgments and perceptions reach unity in quite different ways. To certify that one selfsame proposition (e.g., that the cat is on the mat) returns to our consciousness on several occasions is quite a different task than to certify that one selfsame substantial entity (e.g., this mat-loving cat) returns to our sight every afternoon. Husserl’s early discoveries about unity had to do with judgment, and they were based upon the lived difference between synthetic judgments and analytic judgments. His ambitions then were not primarily metaphysical or epistemological. Moreover, it is relatively easy to “feel” the difference among three sorts of judgment: (a) a synthetic judgment that arbitrarily groups several items together, (b) a synthetic judgment that groups things in recognition of some characteristic that all share independently of the judgment, and (c) a judgment that the unity imputed to a thing is not owing to judgment at all. The distinction among these judgment-forms was already established in the Habilitationsschrift. However the task undertaken in Ideen II is forcibly to transpose that distinction onto perception, and so to come up with a general test for certifying when knowledge is genuinely in touch with reality.

This project is set in motion in # 9, where new terminology is introduced for the threefold distinction first made in “Begriff der Zahl.” (However, now that the transcendental reduction is presupposed, the arrow of causality should be removed. There can be only correlation or its absence.) BZ’s “psychic relation” now becomes “categorial synthesis,” in which perception serendipitously collects disparate items into one group, for no special reason intrinsic to the items. BZ’s “content relation” (or “physical relation”) becomes “aesthetic synthesis” (or “sensuous synthesis”), in which perception recognizes some intrinsic reason for grouping these items and finds itself constrained to do so by something other than mere whim. And BZ’s uncomposed unity (e.g., “that rose there”) becomes the “pure sense-object.”

In BZ, “synthesis” meant a combining judgment: a judgment that erected a set of things with many members. A set with one member–that is, a unified thing–obviously needed no synthesizing judgment to set it up. In Ideen II, however, “synthesis” means a perception that, while receiving multiple impressions (the off-shadings or Abschattungen), composes an object out of them. But this object is a unity, not a group; in fact, it is what Husserl would earlier have called an uncomposed unity. In other words aesthetic synthesis–operating now over partial views, not discrete items–finds that it has a reason for referring those multiple impressions to one object, even though the unity of the thing never gives itself directly to consciousness. What is that reason? This question is enticing, because Husserl is tantalizingly close here to describing a way in which the real unity of things is available for knowledge.

Husserl works on this question in # 15b, where “the spatial body is a synthetic unity of a manifold of strata of ‘sensuous appearances’ of different senses” (42-43). The spatially extended thing is a unity drawing together all the experiences we have had of it, and summoning us toward further experiences of it through sight and touch and our other senses. It achieves its unity as a spatial location, which seems not to depend upon whether or not it is actually perceived.

However, Husserl cautions, this unity alone is insufficient to validate itself. He writes:

“(W)e have first taken the body as independent of all causal conditioning, i.e., merely as a unity which presents itself visually or tactually, through multiplicities of sensations, as endowed with an inner content of characteristic features…. But in what we have said, it is also implied that under the presupposition referred to (namely, that we take the thing outside of the nexuses in which it is a thing) we do not find, as we carry out experiences, any possibility for deciding, in a way that exhibits, whether the experienced material thing is actual or whether we are subject to mere illusion and are experiencing a mere phantom” (43).

Thus, reality is not guaranteed for an isolated item, even when it seems to be giving us a reason to take it as the unified core attracting its manifold appearings to one hub of reference. The central location of the thing is dependent upon its real circumstances, as Husserl goes on to say in # 15c. The reality of “one” depends on “others”; i.e., on thing-connection. The thing is what it is in relation to its surroundings. This becomes apparent when things move and change, for their changes must correlate coherently with reciprocal changes in the things next to them.

Such co-variance is what certifies reality–or materiality, which Husserl seems to equate with it. In # 15c, reality means substantial causality. Within the webwork of material things, everything affects everything else. The real is the causal. Co-variance across the material realm, then, is what certifies the oneness and reality of that realm (# 15e).

Animated bodies also connect in the webwork of material things (# 13). Each of them is a center of appearings, a one, just as every other thing is. However, unlike soulless bodies, each animal is also a zero. It lives at a point of origination. The animal body bears the zero-point of orientation for the pure ego (61), as its absolute “here” (135, 166). Arithmetically, this is a stunning contrast. Every “something” whatsoever is either a one or a one-and-one-and-etc. But the animated body, in addition to being just one of those somethings, is also the one who is zero: the one from whom the counting starts, the one who chooses whether and where it is appropriate to insert the and‘s.

But any series that is initiated by/at/in the living body is counted off nonarbitrarily. Such series go in order; they are “motivated.” This is owing to the movement of the body itself within the material web. The body’s own kinesthetic sense will coordinate with the corresponding changes in sensory perceptions as it navigates among things. Thus, the zero shifts position in relation to the other unified centers to which perceptions accrue; but as it does so, the series of their appearings change in a regular way (63).

What about counting zero’s? Are they multiple; are there many human bodies? Husserl declines to pursue this avenue of approach into the problem of other minds and human community. Intersubjectivity will treated instead as an implication of the reality of the material world, not a precondition for it. The multiplicity of bodies is taken up only on page 83, where it is admitted that the foregoing analysis has been framed on the assumption that there would be only one, “solipsistic,” point-zero in reality. Belatedly, other bodies now are brought into the picture–but not because they are necessary for its unity, or because they have been apprehended among the realities presenting to consciousness. The others are brought in because they are required for the full unification of the thing in reality, whether that thing is one of the physical bodies or my very own live body. To be is to be describable (87). Reality for the thing entails a possibility of appearing to anyone at all. Being counted from one zero-point is not enough for the real thing. To count, it needs the possibility of being counted from multiple directions.

The thing is a rule of appearances. That means that the thing is a reality as a unity of a manifold of appearances connected according to rules. Moreover, this unity is an intersubjective one…. The physicalistic thing is intersubjectively common in that it has validity for all individuals who stand in possible communion with us (91-92).

To be real, the thing must count as a place or location, a center, independently of any particular point of origin. Yet what grants reality to the thing is not some consensus reached by observers. Indeed, the thing may look entirely different to different observers; however, its reality constrains all to agree that, at least, “it is there.” Oddly, then, the real thing is another kind of zero, for its barest reality consists in its being an empty place-holder (91-93).

Finally, Husserl makes unity a synonym for the philosophical term “substance” as traditionally meant. For example, he says that both the soul and the body are unities, so that an analogy obtains between psychic unity and material unity (129, 131). Oneness becomes the ontological form that determines substantial reality (133). The pure ego is one with respect to an individual stream of consciousness, that is, before the transcendental reduction has de-individuated the latter (117); however the pure ego is insubstantial and not one whenever the reduction is in effect (128).

And so Husserl’s quest for unity splinters and spends itself out by diverting into many contradictory projects pursued by the many unharmonized voices of Ideen II. Although the manuscript remained unpublished, it was made available for consultation by a number of Husserl’s younger colleagues. Among the last publication of Husserl’s lifetime was the Cartesian Meditations of 1931, in which he addressed the apparent solipsism of his transcendental phenomenology. That work itself was undergoing a comprehensive reworking in partnership with Husserl’s assistant Eugen Fink during the years before Husserl’s death in 1938.

7. References and Further Reading

Husserl’s publications and his extensive Nachlass are being brought out in a multi-volume critical edition entitled Husserliana – Edmund Husserl, Gesammelte Werke, from Nijhoff in The Hague. The major works published during Husserl’s lifetime are the following:

- Über den Begriff der Zahl. Psychologische Analysen, 1887.

- Philosophie der Arithmetik. Psychologische und logische Untersuchungen, 1891.

- Logische Untersuchungen. Erste Teil: Prolegomena zur reinen Logik, 1900; reprinted 1913.

- Logische Untersuchungen. Zweite Teil: Untersuchungen zur Phänomenologie und Theorie der Erkenntnis, 1901; second edition 1913 (for part one); second edition 1921 (for part two).

- “Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft,” Logos 1 (1911) 289-341.

- Ideen zu einer reinen Ph‰nomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie. Erstes Buch: Allgemeine Einführung in die reine Phänomenologie, 1913.

- “Vorlesungen zur Phänomenologie des inneren Zeitbewusstseins,” Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung 9 (1928), 367-498.

- “Formale und transzendentale Logik. Versuch einer Kritik der logischen Vernunft,” Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung 10 (1929) 1-298.

- Mèditations cartèsiennes, 1931.

- “Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzentale Phänomenologie: Eine Einleitung in die phänomenologische Philosophie,” Philosophia 1 (1936) 77-176.

Works translated into English by Husserl (In chronological order. Publication dates of the German originals are in brackets.)

- “Philosophy as Rigorous Science,” trans. in Q. Lauer (ed.), Phenomenology and the Crisis of Philosophy, New York: Harper [1910], 1965.

- Formal and Transcendental Logic, trans. D. Cairns. The Hague: Nijhoff [1929], 1969.

- The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Philosophy, trans. D. Carr. Evanston: Northwestern University Press

[1936/54], 1970. - Logical Investigations, trans. J. N. Findlay, London: Routledge [1900/01; 2nd, revised edition 1913], 1973.

- Experience and Judgement, trans. J. S. Churchill and K. Ameriks, London: Routledge [1939], 1973.

- Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy – Third Book: Phenomenology and the Foundations of the Sciences, trans. T. E. Klein and W. E. Pohl, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1980.

- Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy — First Book: General Introduction to a Pure Phenomenology, trans. F. Kersten. The Hague: Nijhoff (= Ideas) [1913], 1982.

- Cartesian Meditations, trans. D. Cairns, Dordrecht: Kluwer [1931], 1988.

- Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy – Second Book: Studies in the Phenomenology of Constitution, trans. R. Rojcewicz and A. Schuwer, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1989.

- On the Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time (1893-1917), trans. J. B. Brough, Dordrecht: Kluwer [1928], 1990.

- Early Writings in the Philosophy of Logic and Mathematics, trans. D. Willard, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1994.

- The Essential Husserl, ed. D. Welton, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Further Reading:

- Bell, David (1990) Husserl, London: Routledge.

- Bernet, Rudolf and Kern, Iso and Marbach, Eduard (1993) An Introduction to Husserlian Phenomenology, Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Carr, David (1987) Interpreting Husserl, Dordrecht: Nijhoff.

- Derrida, Jacques (1978) Edmund Husserl’s ‘Origin of Geometry’, trans. J.P. Leavy, New York: Harvester Press, 1978.

- Dreyfus, Hubert (ed.) (1982) Husserl, Intentionality, and Cognitive Science, Cambridge/Mass.: MIT Press.

- Drummond, John (1990) Husserlian Intentionality and Non-Foundational Realism, Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Levinas, E., (1973) The Theory of Intuition in Husserl’s Phenomenology, Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Mohanty, J. N. and McKenna, William (eds.) (1989) Husserl’s Phenomenology: A Textbook, Lanham: University Press of America.

- Smith, Barry and Smith, David Woodruff (eds.) (1995) The Cambridge Companion to Husserl, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sokolowski, Robert (ed.) (1988) Edmund Husserl and the Phenomenological Tradition, Washington: Catholic University of America Press.

- Zahavi, Dan (2003) Husserl’s Phenomenology, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Author Information

Marianne Sawicki

Email: law.sawicki@gmail.com

Huntingdon, Pennsylvania

U. S. A.

The moral philosophy of

The moral philosophy of  Wang Yangming, also known as Wang Shouren (

Wang Yangming, also known as Wang Shouren ( The Theaetetus is one of the middle to later dialogues of the ancient Greek philosopher

The Theaetetus is one of the middle to later dialogues of the ancient Greek philosopher

Aesthetics may be defined narrowly as the theory of beauty, or more broadly as that together with the philosophy of art. The traditional interest in beauty itself broadened, in the eighteenth century, to include the sublime, and since 1950 or so the number of pure aesthetic concepts discussed in the literature has expanded even more. Traditionally, the philosophy of art concentrated on its definition, but recently this has not been the focus, with careful analyses of aspects of art largely replacing it. Philosophical aesthetics is here considered to center on these latter-day developments. Thus, after a survey of ideas about beauty and related concepts, questions about the value of aesthetic experience and the variety of aesthetic attitudes will be addressed, before turning to matters which separate art from pure aesthetics, notably the presence of intention. That will lead to a survey of some of the main definitions of art which have been proposed, together with an account of the recent “de-definition” period. The concepts of expression, representation, and the nature of art objects will then be covered.

Aesthetics may be defined narrowly as the theory of beauty, or more broadly as that together with the philosophy of art. The traditional interest in beauty itself broadened, in the eighteenth century, to include the sublime, and since 1950 or so the number of pure aesthetic concepts discussed in the literature has expanded even more. Traditionally, the philosophy of art concentrated on its definition, but recently this has not been the focus, with careful analyses of aspects of art largely replacing it. Philosophical aesthetics is here considered to center on these latter-day developments. Thus, after a survey of ideas about beauty and related concepts, questions about the value of aesthetic experience and the variety of aesthetic attitudes will be addressed, before turning to matters which separate art from pure aesthetics, notably the presence of intention. That will lead to a survey of some of the main definitions of art which have been proposed, together with an account of the recent “de-definition” period. The concepts of expression, representation, and the nature of art objects will then be covered. “Neo-Confucianism” is the name commonly applied to the revival of the various strands of

“Neo-Confucianism” is the name commonly applied to the revival of the various strands of

For Bonhoeffer, the foundation of ethical behaviour lay in how the reality of the world and the reality of

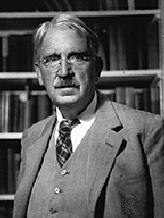

For Bonhoeffer, the foundation of ethical behaviour lay in how the reality of the world and the reality of  One can scarcely imagine a figure with a greater reputation for disapproval of philosophy than John Calvin. The French expatriate penned some of the most vitriolic diatribes against philosophy and its role in scholastic theology ever written. Thus, in one way, this reputation is rather well-earned, and an article upon Calvin in an encyclopedia of philosophy can be rather brief. However, in another way, Calvin’s consideration, knowledge, and use of philosophy in his own work refutes the obscurantist representation left by a surface-level reading. A closer reading of Calvin’s great work, the Institutes of the Christian Religion, along with his commentaries and treatises demonstrates that instead of denying the importance of philosophy, Calvin generally seeks to set philosophy in what he regards as its proper place. His vehemence stems from his belief that the rationalism of some of the scholastics had displaced God’s wisdom, most securely found in the work of the Holy Spirit in the scriptures, as the pinnacle for knowledge of the divine.

One can scarcely imagine a figure with a greater reputation for disapproval of philosophy than John Calvin. The French expatriate penned some of the most vitriolic diatribes against philosophy and its role in scholastic theology ever written. Thus, in one way, this reputation is rather well-earned, and an article upon Calvin in an encyclopedia of philosophy can be rather brief. However, in another way, Calvin’s consideration, knowledge, and use of philosophy in his own work refutes the obscurantist representation left by a surface-level reading. A closer reading of Calvin’s great work, the Institutes of the Christian Religion, along with his commentaries and treatises demonstrates that instead of denying the importance of philosophy, Calvin generally seeks to set philosophy in what he regards as its proper place. His vehemence stems from his belief that the rationalism of some of the scholastics had displaced God’s wisdom, most securely found in the work of the Holy Spirit in the scriptures, as the pinnacle for knowledge of the divine.

The Bakhtin Circle was a 20th century school of Russian thought which centered on the work of Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin (1895-1975). The circle addressed philosophically the social and cultural issues posed by the Russian Revolution and its degeneration into the Stalin dictatorship. Their work focused on the centrality of questions of significance in social life in general and artistic creation in particular, examining the way in which language registered the conflicts between social groups. The key views of the circle are that linguistic production is essentially dialogic, formed in the process of social interaction, and that this leads to the interaction of different social values being registered in terms of reaccentuation of the speech of others. While the ruling stratum tries to posit a single discourse as exemplary, the subordinate classes are inclined to subvert this monologic closure. In the sphere of literature, poetry and epics represent the centripetal forces within the cultural arena whereas the novel is the structurally elaborated expression of popular ideologiekritik, the radical criticism of society. Members of the circle included Matvei Isaevich Kagan (1889-1937); Pavel Nikolaevich Medvedev (1891-1938); Lev Vasilievich Pumpianskii (1891-1940); Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinskii (1902-1944); Valentin Nikolaevich Voloshinov (1895-1936); and others.

The Bakhtin Circle was a 20th century school of Russian thought which centered on the work of Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin (1895-1975). The circle addressed philosophically the social and cultural issues posed by the Russian Revolution and its degeneration into the Stalin dictatorship. Their work focused on the centrality of questions of significance in social life in general and artistic creation in particular, examining the way in which language registered the conflicts between social groups. The key views of the circle are that linguistic production is essentially dialogic, formed in the process of social interaction, and that this leads to the interaction of different social values being registered in terms of reaccentuation of the speech of others. While the ruling stratum tries to posit a single discourse as exemplary, the subordinate classes are inclined to subvert this monologic closure. In the sphere of literature, poetry and epics represent the centripetal forces within the cultural arena whereas the novel is the structurally elaborated expression of popular ideologiekritik, the radical criticism of society. Members of the circle included Matvei Isaevich Kagan (1889-1937); Pavel Nikolaevich Medvedev (1891-1938); Lev Vasilievich Pumpianskii (1891-1940); Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinskii (1902-1944); Valentin Nikolaevich Voloshinov (1895-1936); and others. Sir Francis Bacon (later Lord Verulam and the Viscount St. Albans) was an English lawyer, statesman, essayist, historian, intellectual reformer, philosopher, and champion of modern science. Early in his career he claimed “all knowledge as his province” and afterwards dedicated himself to a wholesale revaluation and re-structuring of traditional learning. To take the place of the established tradition (a miscellany of Scholasticism, humanism, and natural magic), he proposed an entirely new system based on empirical and inductive principles and the active development of new arts and inventions, a system whose ultimate goal would be the production of practical knowledge for “the use and benefit of men” and the relief of the human condition.

Sir Francis Bacon (later Lord Verulam and the Viscount St. Albans) was an English lawyer, statesman, essayist, historian, intellectual reformer, philosopher, and champion of modern science. Early in his career he claimed “all knowledge as his province” and afterwards dedicated himself to a wholesale revaluation and re-structuring of traditional learning. To take the place of the established tradition (a miscellany of Scholasticism, humanism, and natural magic), he proposed an entirely new system based on empirical and inductive principles and the active development of new arts and inventions, a system whose ultimate goal would be the production of practical knowledge for “the use and benefit of men” and the relief of the human condition.

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born on January 3, 106 B.C.E. and was murdered on December 7, 43 B.C.E. His life coincided with the decline and fall of the Roman Republic, and he was an important actor in many of the significant political events of his time, and his writings are now a valuable source of information to us about those events. He was, among other things, an orator, lawyer, politician, and philosopher. Making sense of his writings and understanding his philosophy requires us to keep that in mind. He placed politics above philosophical study; the latter was valuable in its own right but was even more valuable as the means to more effective political action. The only periods of his life in which he wrote philosophical works were the times he was forcibly prevented from taking part in politics.

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born on January 3, 106 B.C.E. and was murdered on December 7, 43 B.C.E. His life coincided with the decline and fall of the Roman Republic, and he was an important actor in many of the significant political events of his time, and his writings are now a valuable source of information to us about those events. He was, among other things, an orator, lawyer, politician, and philosopher. Making sense of his writings and understanding his philosophy requires us to keep that in mind. He placed politics above philosophical study; the latter was valuable in its own right but was even more valuable as the means to more effective political action. The only periods of his life in which he wrote philosophical works were the times he was forcibly prevented from taking part in politics.

Juan Donoso Cortés, parliamentary statesman, diplomat, government minister, royal counselor, theologian, and political theorist, may not be well known among modern political philosophers. However, his ideas had an enormous influence in the spheres of politics and religion in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Donoso’s theories were uniquely influential in shaping the ideological trajectory that began with the reaction against the Enlightenment and the French Revolution in the eighteenth century and culminated in the rise of fascism in the twentieth century. This Spanish Catholic and conservative thinker was the philosophical heir of Joseph de Maistre, one of the most prominent reactionary conservative thinkers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Even though his life was short and his works few in number, Donoso’s contribution to modern political philosophy and theology cannot be ignored if we wish to have a more complete understanding of the ideas and actions that have shaped Europe and the Roman Church in recent centuries. His most notable idea—the theory on dictatorship—was Donoso’s most significant and unique contribution to modern political thought.