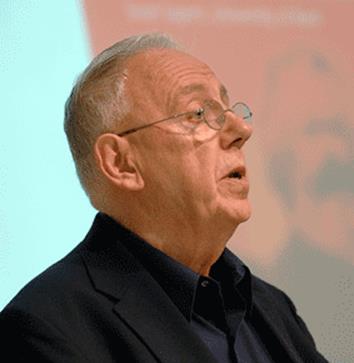

Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre (1929— )

Alasdair MacIntyre is a Scottish born, British educated, moral and political philosopher who has worked in the United States since 1970. His work in ethics and politics reaches across disciplines, drawing on sociology and philosophy of the social sciences as well as Greek and Latin classical literature.

Alasdair MacIntyre is a Scottish born, British educated, moral and political philosopher who has worked in the United States since 1970. His work in ethics and politics reaches across disciplines, drawing on sociology and philosophy of the social sciences as well as Greek and Latin classical literature.

MacIntyre began his career as a Marxist, but in the late 1950s, he started working to develop a Marxist ethics that could rationally justify the moral condemnation of Stalinism. That project eventually led him to reject Marxism along with every other form of “modern liberal individualism” and to propose Aristotle’s ethics as a more effective way to renew moral agency and practical rationality through small-scale moral formation within communities.

MacIntyre’s best known book, After Virtue (1981), is the product of this long ethical project. After Virtue diagnoses contemporary society as a “culture of emotivism” in which moral language is used pragmatically to manipulate attitudes, choices, and decisions, so that contemporary moral culture is a theater of illusions in which objective moral rhetoric masks arbitrary choices. MacIntyre followed After Virtue with two books examining the role that traditions play in judgments about truth and falsity, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988) and Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (1990). MacIntyre’s next major work, Dependent Rational Animals: Why Human Beings Need the Virtues (1999), investigates the social needs and social debts of human agents, and the role that a community plays in the formation of an independent practical reasoner. The remainder of MacIntyre’s mature work extends and supplements the arguments of these four major works.

MacIntyre’s philosophy is important to the fields of virtue ethics and communitarian politics, but MacIntyre has denied belonging to either school of thought. MacIntyre has identified himself as a Thomist since 1984, but some Thomists question his Thomism because he emphasizes Thomas Aquinas’s treatment of human agency but rejects the neo-Thomist project of a creating a Thomist moral epistemology based on the metaphysics of human nature. MacIntyre continues to point out the irrelevance of conventional business ethics, conceived as an application of modern moral theories to business decision making, but some scholars in the field of business ethics have begun to apply MacIntyre’s Aristotelian account of agency and virtue to the study of organizational systems, to develop ways of renewing moral agency and practical rationality within companies. MacIntyre has played an important role in the renewal of Aristotelian ethics and politics in the last three decades, and has made a valued contribution to the advancement of Thomistic philosophy.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Prefatory Comment on “Modern Liberal Individualism”

- Development since 1951

- Major works since 1977

- The Main Themes of MacIntyre’s Philosophy

- References and Further Reading

1. Life

Alasdair MacIntyre was born January 12, 1929 in Glasgow, Scotland. His parents, both of which were physicians, were born and raised in the West of Scotland. Though Educated in England, he learned Scots Gaelic from one of his aunts. MacIntyre grew up in and around the city of London. He earned a bachelor’s degree in classics from Queen Mary College in the University of London in the city’s East End in 1949. MacIntyre attended graduate school at Manchester University, a provincial “red brick” university in the North West of England, earning his MA in Philosophy in 1951.

MacIntyre’s family had distant ties to County Donegal, in the North of Ireland, and his knowledge of Gaelic helped MacIntyre to make connections to the people there. He has remained close to the cultural and political concerns of Ireland for many years. MacIntyre “has an intimate and extensive knowledge of Irish literature, both in English and in Irish” (O’Rourke, p. 3). An academic conference celebrating MacIntyre’s eightieth birthday, held at the University College Dublin in 2009, acknowledged and celebrated his ties to the Irish community.

Alasdair MacIntyre’s philosophy builds on an unusual foundation. His early life was shaped by two conflicting systems of values. One was “a Gaelic oral culture of farmers and fishermen, poets and storytellers.” The other was modernity, “The modern world was a culture of theories rather than stories” (MacIntyre Reader, p. 255). MacIntyre embraced both value systems, and carried those divergent worldviews into his undergraduate education.

As a classics major at Queen Mary College in the University of London (1945-1949), MacIntyre read the Greek texts of Plato and Aristotle, but his studies were not limited to the grammars of ancient languages. He also examined the ethical theories of Immanuel Kant and John Stuart Mill. He attended the lectures of analytic philosopher A. J. Ayer and of philosopher of science Karl Popper. He read Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico Philosophicus, Jean-Paul Sartre’s L’existentialisme est un humanisme, and Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Napoleon Bonaparte (What happened, pp. 17-18). MacIntyre met the sociologist Franz Steiner, who helped direct him toward approaching moralities substantively (interview with Giovanna Borradori, p. 259). MacIntyre’s mature work continues to bridge across conventional disciplinary borders.

MacIntyre’s mature writings also continue to criticize the social and economic orders of modern life. This work also began during his time at Queen Mary College, growing out of his solidarity with the poor and working classes who filled the East End of London where Queen Mary College is located. MacIntyre’s first encounter with the Marxist critiques of liberalism and capitalism (Kinesis Interview, p. 48) drew MacIntyre into two decades of participation in Marxist organizations (Alasdair MacIntyre’s Engagement with Marxism, pp. xiii-l). MacIntyre’s first encounter with the Thomist critique of English social and political life made a strong impression on MacIntyre, but he would not identify himself as a Thomist until 1984 (What happened, p. 17).

From Marxism, MacIntyre learned to see liberalism as a destructive ideology that undermines communities in the name of individual liberty and consequently undermines the moral formation of human agents (interview with Giovanna Borradori, p. 258; Kinesis Interview , p. 47). MacIntyre still acknowledges the insights of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Napoleon Bonaparte (What happened, pp. 20, 483), a book that strips the ideological pretensions from mid-nineteenth century French political rhetoric. For MacIntyre, Marx’s way of seeing through the empty justifications of arbitrary choices to consider the real goals and consequences of political actions in economic and social terms would remain the principal insight of Marxism. MacIntyre found the predictive theories of Marxist social science less convincing. His first book, Marxism: An Interpretation, (1953), criticizes Marx’s turn to social science; similar critiques appear in nearly all of MacIntyre’s major works.

MacIntyre began his teaching career at the University of Manchester as a Lecturer in the Philosophy of Religion in 1951, and held that post until 1957. In a 1956 essay, “Manchester: The Modern University and the English Tradition,” MacIntyre writes with pride about the role of the provincial universities as centers of professional education that are tied in service to the people of their cities, as places that had traditionally been homes to radical politics and non-conformist and minority (Agnostic, Roman Catholic, and Jewish) religion. Marxism: An Interpretation, is similarly an expression of radical politics and non-conformist religion directed to the service of people’s needs. After Manchester, MacIntyre became a member of Britain’s New Left (Alasdair MacIntyre’s Engagement with Marxism, pp. xxii-xxxii, 86-93) and moved through teaching, research, and administrative positions at other British universities before emigrating from Britain to the United States in 1970, where his research interests drew him to teaching posts at Brandeis, Boston University, Vanderbilt, Notre Dame, and Duke. MacIntyre returned to Notre Dame in 2000 as the Senior Research Professor in the Notre Dame Center for Ethics and Culture until his retirement in 2010.

MacIntyre began his career as a Marxist Protestant Christian philosopher of religion, basing his work on the fideism of Karl Barth and Wittgenstein’s concept of a form of life (interview with Giovanna Borradori, p. 257). By 1960 he had stopped writing on that subject, and he wrote as an atheist through the sixties and seventies. MacIntyre’s emigration from Great Britain roughly coincides with his break from organized Marxism. In 1968, MacIntyre published a heavily revised version of Marxism: An Interpretation as Marxism and Christianity, and noted in the preface to the new book that he had become skeptical of both. That skepticism remains in Against the Self-Images of the Age (1971).

During the years 1977 through 1984 MacIntyre transitioned to an Aristotelian worldview, returned to the Christian faith and turned from Aristotle to Thomas Aquinas. MacIntyre explains in the preface to The Tasks of Philosophy (2006) that the article “Epistemological Crises, Dramatic Narrative, and the Philosophy of Science” (hereafter EC, 1977) marks the beginning of this transition.

After his retirement from teaching, MacIntyre has continued his work of promoting a renewal of human agency through an examination of the virtues demanded by practices, integrated human lives, and responsible engagement with community life. He is currently affiliated with the Centre for Contemporary Aristotelian Studies in Ethics and Politics (CASEP) at London Metropolitan University.

Alasdair MacIntyre has authored 19 books and edited five others. His most important book, After Virtue (hereafter AV, 1981), has been called one of the most influential works of moral philosophy of the late 20th century. AV and his other major works, including Marxism: An Interpretation (hereafter MI, 1953), A Short History of Ethics (hereafter SHE, 1966), Marxism and Christianity (hereafter M&C, 1968), Against the Self-Images of the Age (hereafter ASIA, 1971), Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (hereafter WJWR, 1988), Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (hereafter 3RV, 1990), and Dependent Rational Animals (Hereafter DRA, 1999) have shaped academic moral philosophy for six decades. SHE served as a standard text for college courses in the history of moral philosophy for many years; AV remains a widely used ethics textbook in undergraduate and graduate education. MacIntyre has published about two hundred journal articles and roughly one hundred book reviews, addressing concerns in ethics, politics, the philosophy of the social sciences, Marxist theory, Marxist political practice, the Aristotelian notion of excellence or virtue in human agency, and the interpretation of Thomistic metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics.

MacIntyre’s mature work, initiated by the 1977 essay, “Epistemological Crises, Dramatic Narrative, and the Philosophy of Science” (hereafter EC), draws upon the study of traditions, and the examination of the narratives that inform traditions of scientific, philosophical, and social practice, as a philosophical method. AV and the whole body of work that follows it employ this philosophical method in the study of moral and political philosophy.

2. Prefatory Comment on “Modern Liberal Individualism”

AV rejects the view of “modern liberal individualism” in which autonomous individuals use abstract moral principles to determine what they ought to do. The critique of modern normative ethics in the first half of AV rejects modern moral reasoning for its failure to justify its premises, and criticizes the frequent use of the rhetoric of objective morality and scientific necessity to manipulate people to accept arbitrary decisions. The critical argument gives examples of such manipulative moral rhetoric in ordinary speech, in philosophical ethics, and in the political use of the social sciences. The second half of AV proposes a conception of practice and practical reasoning and the notion of excellence as a human agent as an alternative to modern moral philosophy, presenting what MacIntyre has called “an historicist defense of Aristotle” (AV, p. 277).

MacIntyre’s use of the term “modern liberal individualism” in philosophy is not equivalent to “liberalism” in contemporary politics. Some readers interpreted MacIntyre’s rejection of “modern liberal individualism” to mean that he is a political conservative (AV, 3rd ed., p. xv), but MacIntyre uses “modern liberal individualism” to name a much broader category that includes both liberals and conservatives in contemporary American political parlance, as well as some Marxists and anarchists (See ASIA, pp. 280-284). Conservatism, liberalism, Marxism, and anarchism all present the autonomous individual as the unit of civil society (see “The Theses on Feuerbach: A Road Not Taken.”); none of these political theories can provide a well-developed conception of the common good; and none of them can adequately explain or justify any shared pursuit of any common good.

The sources of modern liberal individualism—Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau—assert that human life is solitary by nature and social by habituation and convention. MacIntyre’s Aristotelian tradition holds, on the contrary, that human life is social by nature. Modern liberal individualism seeks to justify the moral authority of various universal, impersonal moral principles to enable autonomous individuals to make morally correct decisions. But modern moral philosophers use those principles to establish the authority of universal moral norms, and modern autonomous individuals set aside the pursuit of their own goods and goals when they obey these principles and norms in order to judge and act morally. MacIntyre rejects this modern project as incoherent. MacIntyre identifies moral excellence with effective human agency, and seeks a political environment that will help to liberate human agents to recognize and seek their own goods, as components of the common goods of their communities, more effectively. For MacIntyre therefore, ethics and politics are bound together.

3. Development since 1951

Alasdair MacIntyre’s career in moral and political philosophy has passed through many changes, but two themes have remained constant. The first is his critique of modern normative ethics. The second is his approach to moral philosophy as a study of moral formation that strengthens rational human agency and helps to develop a political community of rational agents. The critique of modern normative ethics draws on two sources, the philosophy of Karl Marx, and the emotivism of early twentieth-century logical positivists, including A. J. Ayer and C. L. Stevenson. The search for a truthful ethics and politics of agents in communities draws on action theory, sociology, the philosophy of science and the theme of “revolutionary practice” drawn from Karl Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach.

a. The influence of Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach in MacIntyre’s Moral and Political Work

MacIntyre has cited the third of Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach, throughout his career (See MI, p. 61; M&C, p. 59, AV, p. 84); he explains the significance of the Theses on Feuerbach in detail in “The Theses on Feuerbach: A Road Not Taken” (hereafter ToF:RNT), published in 1994. Macintyre reads The Theses on Feuerbach as “a genuinely transitional text” (ToF:RNT, p. 224),” marking the end of Marx’s philosophical work with Hegel and Feuerbach, but “pointing in a direction which Marx did not in fact take” (ToF:RNT, p. 226). Hegel and Feuerbach had been critics of “the standpoint of civil society”; which is effectively the standpoint of “modern liberal individualism.” Feuerbach had criticized objects of religious belief as projections of human thought. But Marx found that the theoretical objects of Feuerbach’s philosophy were susceptible to the same critique. In the Theses on Feuerbach, Marx proposed a philosophy that sets aside the contemplation of theoretical objects in order to examine and transform human activity and practice (ToF:RNT, pp. 227-8; see Marx, fourth and first theses).

In the third thesis, Marx complained that Feuerbach and other materialist social theorists invented a determinist theory of human behavior, but applied it as if it did not encompass their own free agency, as if they were superior to society (ToF:RNT, p. 229-30; see also AV, p. 84). Rejecting this implicit distinction between society and those superior to it, Marx insisted that the leaders and followers of the revolution can only act together, discovering together the ends and methods of the revolution (ToF:RNT, p. 230-1). Marx made this proposal, but did not pursue it. Later Marxist revivals of philosophy have followed two main roads of research, “the dialectical and historical materialism of Plekhanov . . . or . . . the rational voluntarism of the young Lukács” (ToF:RNT, p. 232). For MacIntyre, even at the beginning of his career, The Theses on Feuerbach offered a less traveled road for the recovery of Marxist philosophy that would become essential to MacIntyre’s contributions to moral and political philosophy.

b. Three Phases in MacIntyre’s Career

Discussing his career in an interview for the journal Cogito in 1991, MacIntyre identified three distinct phases in his development. During the first period, from 1949 to 1971, MacIntyre published in the philosophy of religion, ethics, the philosophy of the social sciences, and Marxist political and ethical theory without integrating these studies into a unified world view. During the second period, from 1971 to 1977, MacIntyre worked toward the integration of his philosophy. In the third period, from 1977 forward, MacIntyre has been working on “a single project, to which AV, WJWR and 3RV are all central” (Interview for Cogito, in The MacIntyre Reader, p. 269)

i. Early Career (1949-1971)

In his early career, MacIntyre investigated the rational justification of theories and beliefs, and published books and articles in the philosophy of religion, the philosophy of the social sciences, and moral theory. This survey of his early career will take each of these fields in turn.

1. Philosophy of Religion

In the philosophy of religion, the young MacIntyre did not try to justify religious belief rationally; rather he tried to show that religious belief should be exempted from rational examination. The theory he developed in the 1950s was a defensive structure devised to separate MacIntyre’s religious beliefs from the rest of his academic work. MacIntyre’s early fideist philosophy of religion was influenced by the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein and the theology of Karl Barth. For the fideist, religious belief is not, and cannot be rational; its only basis is the acceptance of religious authority. MacIntyre’s Barthian-Wittgensteinian philosophy of religion is nothing more than a rational compartmentalization of religious belief.

The key statement of MacIntyre’s early fideist philosophy of religion is his 1957 essay, “The Logical Status of Religious Belief,” published in the book Metaphysical Beliefs. This essay faced strong criticism from the atheist Antony Flew and the Christian theologian Basil Mitchell. In a 1958 book review, Flew pointed out that traditional Christianity had a closer connection to empirical facts than MacIntyre allowed, and that even if facts about the world could not verify religious belief, it was nonetheless possible for internal incoherence to demonstrate the falsehood of doctrine. Mitchell published a fourteen page critique of MacIntyre’s fideism in 1961 entitled, “The Justification of Religious Belief.” When Metaphysical Beliefs was republished in 1970, MacIntyre added a new preface in which he thanked Flew and Mitchell, along with his colleague Ronald Hepburn, for their criticism, and rejected the essay’s “irrationalism as both false and dangerous” (“Preface to the 1970 Edition,” pp. x–xi).

From the early 1960s through the late 1970s, MacIntyre wrote as an avowed atheist. Three publications in the 1960s, “God and the Theologians,” The Religious Significance of Atheism, and Secularization and Moral Change, express MacIntyre’s atheist convictions.

The reasoning behind MacIntyre’s rejection of his early fideism continues to inform his approach to theism. MacIntyre’s 2010 lecture, “On Being a Theistic Philosopher in a Secularized Culture” does not treat theistic belief as an isolable metaphysical doctrine about the origin and fate of human life. For the mature MacIntyre, theism plays a central role in the interpretation of the world. MacIntyre’s mature theism is not a return to his early fideism; it belongs to a rational worldview that challenges “secular fideists” on the same grounds that it challenges religious ones (WJWR, p. 5).

2. Philosophy of the Social Sciences

MacIntyre’s early work in the philosophy of the social sciences is related to the rational justification of Marxist theory, and to distinguishing the more promising elements of Marx’s early philosophical work from the more pseudoscientific elements of later Marxist and Stalinist theory. Within Marxism, which presented itself through most of the twentieth century as a social science, MacIntyre directed his critique against the crude determinism of Stalinism. More broadly, MacIntyre has questioned the rational justification of any social theory that does not give a central place to the beliefs, intentions, and choices of human agents.

In his unpublished master’s thesis, The Significance of Moral Judgements (hereafter SMJ, 1951), MacIntyre cites Steven Toulmin, “The Logical Status of Psycho-Analysis,” Antony Flew, “Psycho-Analytic Explanation,” and Richard Peters, “Cause, Cure, and Motive,” to criticize Sigmund Freud’s apparent reduction of the moral account of a person’s actions to a causal account of that person’s psychological condition.

MacIntyre remained an outspoken critic of determinist social science throughout the early period of his career. Marxism: An Interpretation criticizes Marx’s turn to determinist social science in The German Ideology (MI, pp. 68-78). M&C, revises this criticism, directing the blame toward Friedrich Engels (M&C, pp.70-74). In the article, “Determinism,” MacIntyre admitted that successful predictions about human behavior from the social sciences made it difficult to dismiss determinism, but given the kinds of interpretative choices required to defend determinism, he found “it difficult to see how determinism could ever be verified or falsified” (pp. 39-40).

3. Ethics and Politics

MacIntyre’s critique of modern normative ethics, if understood as a critique of the normative ethics characteristic of liberal modernity, is rooted partly in the work of Karl Marx. While still a student, MacIntyre had accepted much of the Marxist critique of modern liberal politics as an ideology that sets the individual against the interests of the community. Marx dismissed the notion of “natural rights” as a residue of feudal society in the book review, “On The Jewish Question.” For Marx, “rights” could arise only from laws made by governments. Marx held that “natural rights” or the “rights of man,” as used in nineteenth century liberal politics, served only to protect the individual from the society to which he belonged, and thus threatened both the society and the individual.

MacIntyre’s early Marxism led him to reject every form of modern liberal individualism, “including the liberalism of contemporary American and English conservatives, as well as that of American and European radicals, and even the liberalism of the self-proclaimed liberals.” For these ideological stances, by their constructions of civil society as a response of the individual to universal standards of reason and behavior, “impose a certain kind of unacknowledged domination, and one which in the long run tends to dissolve traditional human ties and to impoverish social and cultural relationships” (Borradori interview, p. 258)

MacIntyre’s critique of modern normative ethics is also influenced by the theory of emotivism. C. L. Stevenson and other emotivists held that moral judgments signify only the subjective interests of their authors, rather than any objective characteristic of the agents and actions they judge. SMJ takes issue with the reductivism of Stevenson’s theory of the meaning of moral judgments, but MacIntyre agrees with most points of Stevenson’s emotivist critique of modern normative ethics, and in this way MacIntyre joins Stevenson’s critique of the intuitionism of G. E. Moore.

Moore had argued in Principia Ethica (1903) that the fundamental task of philosophical ethics was to investigate “assertions about that property of things which is denoted by the term ‘good,’ and the converse property denoted by the term ‘bad’” (Principia Ethica, §23) Moore asserted that “good” must name some specific quality that all good things share, but he found it impossible to define “good” in any adequate way (Principia Ethica, §10). Moore therefore described “good” as a simple, indefinable, non-natural quality.

Logical positivists, including A. J. Ayer (Language Truth and Logic, ch. 6) and C. L. Stevenson could find nothing objective in the “good” that Moore described, and concluded that “good” and “bad” are not objective qualities. Stevenson held that valuations, like “this is a good car” or “that is a good house,” and moral valuations, like “he is a good man,” or “theft is wrong,” are not statements of fact. For Stevenson, evaluative words like “good” and “evil” carry, “emotive meaning” which Stevenson defines as “a tendency of a word, arising through the history of its usage, to produce (result from) affective responses to people” (“The Emotive Meaning of Ethical Terms” p. 23) Emotive terms are used to influence people. Thus the true meaning of any valuation, and particularly of any moral valuation—the significance of moral judgments—is either the speaker’s subjective approval and recommendation, or the speaker’s subjective rejection and proscription. In short, the emotivists held that moral judgments communicate neither facts nor beliefs; they communicate only the emotional interests of their authors.

MacIntyre criticized the reductivism of Stevenson’s conclusions in his MA thesis, but MacIntyre did not criticize Stevenson’s rejection of Moore. MacIntyre explains, “This is not to deny the emotive character of the moral judgment: it is to suggest that when we have said of moral judgments that they are emotive we have left a great deal unsaid—and even the emotive may have a logic to be mapped” (SMJ, p. 89.) MacIntyre’s 1951 assessment of emotivism accepts Stevenson’s critique of the referential meaning of moral judgments (SMJ, p. 74), and with it, the general rejection of “traditional moral philosophy” as a study that uses principles to assess facts (SMJ, p. 81).

For MacIntyre ethics is not an application of principles to facts, but a study of moral action. Moral action, free human action, involves decisions to do things in pursuit of goals, and it involves the understanding of the implications of one’s actions for the whole variety of goals that human agents seek. In this sense, “To act morally is to know how to act” (SMJ, p. 56). “Morality is not a ‘knowing that’ but a ‘knowing how’” (SMJ, p. 89). If human action is a ‘knowing how,’ then ethics must also consider how one learns ‘how.’ Like other forms of ‘knowing how,’ MacIntyre finds that one learns how to act morally within a community whose language and shared standards shape our judgment (SMJ, pp. 68-72). MacIntyre had concluded that ethics is not an abstract exercise in the assessment of facts; it is a study of free human action and of the conditions that enable rational human agency.

Human agency remains a central theme in MacIntyre’s first published book, Marxism: An Interpretation (1953). The book praises those forms of M&C that enable human agency, and criticizes those that inhibit human agency. MacIntyre traces a history from Protestant theology and practice, through the philosophies of Hegel and Feuerbach, to the work of Marx to argue that Marxism is a transformation of Christianity. MacIntyre gives Marx credit for concluding in the third of the Theses on Feuerbach, that the only way to change society is to change ourselves, and that “The coincidence of the changing of human activity or self-changing can only be comprehended and rationally understood as revolutionary practice” (Marx, Theses on Feuerbach, quoted in MI, p. 61). MacIntyre criticizes Marx’s subsequent turn to determinist social science and concludes that “Marx’s transition from prophecy to prediction” transforms Marxism into an alienating myth that divides human beings between “the good who accept Marxism, [and] the wicked who reject it” (MI, p. 89).

The book also examines some shortcomings of Protestant theology and practice, showing how the demands of the gospel inform the ideals of Feuerbach and, through Feuerbach, Marx. MacIntyre distinguishes “religion which is an opiate for the people from religion which is not” (MI, p. 83). He condemns forms of religion that justify social inequities and encourage passivity. He argues that authentic Christian teaching criticizes social structures and encourages action (MI, pp. 119-22).

The MA thesis and MI combine to chart MacIntyre’s initial reply to the emotivist critique of modern normative ethics. They also prefigure MacIntyre’s conflict with R. M. Hare’s response to emotivism. Hare sought to defend modern normative ethics from the emotivist challenge with an alternative account of the meaning of moral judgments. A central claim of Hare’s The Language of Morals (1952), renewed in Freedom and Reason (1963), is that moral judgments are descriptive—not merely emotive—because they are both universalizable and prescriptive. For Hare, universalizability stems from an agent’s commitment to use terms and judgments consistently. For example, “If a person says that a thing is red, he is committed to the view that anything which was like it in the relevant respects would likewise be red” (Freedom and Reason, I 2.2). Thus the prescriptive judgments that agents make are universalizable, insofar as those agents are committed to judging similar things similarly; and it is the universalizability of these prescriptive judgments that gives them descriptive meaning. In short, moral judgments are descriptive because they describe the values chosen by their authors.

MacIntyre rejected Hare’s defense of modern normative ethics in his 1957 essay, “What Morality Is Not.” MacIntyre focuses on Hare’s theory: “It is widely held that it is of the essence of moral valuations that they are universalizable and prescriptive. This is the contention which I wish to deny.” “What Morality is Not” explores the variety of meanings and intentions carried by moral judgments. MacIntyre lists six kinds of moral valuations that are neither universalizable nor prescriptive and concludes that the theory of universal prescriptivism is inadequate for the same reason that emotivism is inadequate; it is reductive. Universal prescriptivism simply fails to give a complete account of the meaning of moral judgments.

“What Morality is Not” also argues that the procedures of modern moral philosophy are superfluous to real moral practice. Where “moral philosophy textbooks” discuss the kinds of maxims that should guide “promise-keeping, truth-telling, and the like,” moral maxims do not guide real agents in real life at all. “They do not guide us because we do not need to be guided. We know what to do” (ASIA, p. 106). Sometimes we do this without any maxims at all, or even against all the maxims we know. MacIntyre Illustrates his point with Huckleberry Finn’s decision to help Jim, Miss Watson’s escaped slave, to make his way to freedom (ASIA, p. 107). Once again, morality is not a “knowing that” but a “knowing how,” and the use of this “knowing how” cannot be reduced to making universalizable prescriptive judgments. MacIntyre’s rejection of Hare’s universal prescriptivism renewed his critique of modern normative ethics, and carried lasting consequences for the Marxist MacIntyre’s response to the moral challenge of Stalinism.

In the late 1950s Marxists throughout the world discovered the hidden atrocities of the Stalinist regime in the Soviet Union, and witnessed the violent suppression of the Hungarian revolution of 1956 (See Virtue and Politics, pp. 134-151). The crimes of the Stalinist regime, including mass murder, mass deportation, and the execution of the intellectual, political, cultural, and ecclesial leadership of subject national communities, demanded condemnation. Yet the moral criticism of Stalinist policies presented a problem to committed Marxist atheists, including MacIntyre, who had rejected theistic notions of divine law as well as modern secular notions of “natural rights.”

MacIntyre discussed the moral condemnation of Stalinism in “Notes from the Moral Wilderness” I & II, (1958 and 59). For MacIntyre, it appeared difficult to condemn Stalinism with any real authority, because any appeal to modern secular liberal moral principle seems to be essentially arbitrary. The ex-communist, liberal critic of Stalinism “can only condemn in the name of his own choice” (The MacIntyre Reader, p. 34). MacIntyre’s description of the moral perplexity of these critics of Stalinism resembles his description of Huck Finn a year earlier (ASIA, p. 106); they judged the crimes of Stalin well, but lacked any adequate way to justify their judgments rationally. In “Notes From the Moral Wilderness II,” MacIntyre proposed a new Marxist ethics of human action. Rather than divorcing “the ‘ought’ of morality” from “the ‘is’ of desire” (The MacIntyre Reader, p. 41), MacIntyre’s Marxist ethics would look to “the fact of human solidarity which comes to light in the discovery of what we want” (The MacIntyre Reader, p. 48).

MacIntyre’s Marxist writings of the early 1960s develop his ethical project. “Communism and British Intellectuals” (1960) argues that the Communist Party of Great Britain is no longer Marxist because it has abandoned Marx’s insight from the third of the Theses on Feuerbach. “Classical Marxism . . . wants to transform the vast mass of mankind from victims and puppets into agents who are masters of their own lives,” but Stalinism had transformed Marxism into the doctrine that scientists should use “the objective and unchangeable laws of history” to manage the behavior of society (Alasdair MacIntyre’s Engagement with Marxism, p. 119). “Freedom and Revolution” (1960) discusses “human initiative” in terms of “desire, intention, and choice” (Alasdair MacIntyre’s Engagement with Marxism, p. 124), and sees the full development of human freedom to require participation in the life of a community: “The problem of freedom is not the problem of the individual against society but the problem of what sort of society we want, and what sort of individuals we want to be” (Alasdair MacIntyre’s Engagement with Marxism, p. 129). The individual should not seek liberation from society, but through society. Morality has to do with one’s participation in the life of one’s community.

MacIntyre develops the ideas that morality emerges from history, and that morality organizes the common life of a community in SHE (1966). The book concludes that the concepts of morality are neither timeless nor ahistorical, and that understanding the historical development of ethical concepts can liberate us “from any false absolutist claims” (SHE, p. 269). Yet this conclusion need not imply that morality is essentially arbitrary or that one could achieve freedom by liberating oneself from the morality of one’s society. In his comments on Plato’s Gorgias in chapter 4, MacIntyre rejects Callicles’ claims that breaking social rules can be liberating. “For a man whose behavior was not rule-governed in any way would have ceased to participate as an intelligible agent in human society” (SHE, p. 32). Elements of SHE return in the histories of AV (1981) and WJWR (1988).

ii. Interim (1971-1977)

The publication of ASIA in 1971 marks the end of the “heterogeneous, badly organized, sometimes fragmented and often frustrating and messy enquiries” (The MacIntyre Reader, p. 268) that made up the first part of MacIntyre’s career, and the beginning of “an interim period of sometimes painfully self-critical reflection” that would end with the publication of EC in 1977.

ASIA is a collection of short essays criticizing ideology, contemporary religious practice, Marxist theory and hagiography, modern moral philosophy, reductive approaches to the social sciences, and modern liberal individualism. The essays in the book address most of the issues that would appear a decade later in AV, but they are not synthesized into a single coherent narrative “because,” MacIntyre explains in the preface, “to rescue them from their form as reviews or essays written at a particular time or place would require that I should know how to tie these arguments together into a substantive whole. This I do not yet know how to do. . .” (ASIA, p. x). As MacIntyre himself reports, he spent the interim period from 1971 to 1977 working to bring unity to his philosophical writing (The MacIntyre Reader, p. 268-9). ASIA is a valuable companion to AV because some issues that are treated obscurely in the latter, for example Trotsky’s assessment of the Russian Revolution, are treated in detail in the former (AV, p. 262; ASIA, pp. 52-59).

ASIA’s final essay, “Political and Philosophical Epilogue: A View of The Poverty of Liberalism by Robert Paul Wolff,” introduces some of the most characteristic claims of AV: Various forms of modern liberalism appeal to different theories and principles for their justification. The theories that are used to justify liberal principles may serve as ideological masks that enable “those who profess the principles to deceive not only others but also themselves as to the character of their political action” (ASIA, p. 282). “American conservatism,” “American liberalism,” and “American radicalism” are all forms of modern liberalism, thus “To free ourselves from liberalism, radicalism is the wrong remedy.” Marxism cannot fulfill its promise to teach us how to transform society, but “we can at least learn from it where not to begin” (ASIA, p. 284).

In the Cogito interview, MacIntyre says that by 1971 he had begun to look to Aristotle as the right place to begin to study society in order to understand it and transform it. He “set out to rethink the problems of ethics in a systematic way, taking seriously for the first time the possibility that the history both of modern morality and of modern moral philosophy could only be written adequately from an Aristotelian point of view” (The MacIntyre Reader, p. 268).

For MacIntyre, “an Aristotelian point of view” sees teleology inherent in the natures of things, interprets deliberate human activity as voluntary action—not as caused behavior, and finds the human person to be naturally social. From this “Aristotelian point of view,” “modern morality” begins to go awry when moral norms are separated from the pursuit of human goods and moral behavior is treated as an end in itself. This separation characterizes Christian divine command ethics since the fourteenth century and has remained essential to secularized modern morality since the eighteenth century. From MacIntyre’s “Aristotelian point of view,” the autonomy granted to the human agent by modern moral philosophy breaks down natural human communities and isolates the individual from the kinds of formative relationships that are necessary to shape the agent into an independent practical reasoner.

iii. Mature Work (1977- )

In the Preface to The Tasks of Philosophy (2006), MacIntyre explains that the discontinuities of ASIA left him with the question, “How then was I to proceed philosophically?” MacIntyre’s answer came in the 1977 essay “Epistemological Crises, Dramatic Narrative, and the Philosophy of Science” (Hereafter EC). This essay, MacIntyre reports, “marks a major turning-point in my thought in the 1970s” (The Tasks of Philosophy, p. vii) EC may be described fairly as MacIntyre’s discourse on method, and as the title suggests, it presents three general points on the method for philosophy.

First, Philosophy makes progress through the resolution of problems. These problems arise when the theories, histories, doctrines and other narratives that help us to organize our experience of the world fail us, leaving us in “epistemological crises.” Epistemological crises are the aftermath of events that undermine the ways that we interpret our world. Epistemological crises may be deeply personal, triggered by unexpected betrayal or by the loss of religious faith or ideological commitment, or they may be highly speculative, brought on by the failure of trusted theories to explain our experience. To live in an epistemological crisis is to be aware that one does not know what one thought one knew about some particular subject and to be anxious to recover certainty about that subject.

To resolve an epistemological crisis it is not enough to impose some new way of interpreting our experience, we also need to understand why we were wrong before: “When an epistemological crisis is resolved, it is by the construction of a new narrative which enables the agent to understand both how he or she could intelligibly have held his or her original beliefs and how he or she could have been so drastically misled by them” (EC, in The Tasks of Philosophy, p. 5). The resolution of the crisis may lead one to recognize that human understanding is always incomplete and that progress in enquiry is therefore open ended. For MacIntyre, the resolution of an epistemological crisis cannot promise the neat clarity of a shift from a failed body of theory to a truthful one.

To illustrate his position on the open-endedness of enquiry, MacIntyre compares the title characters of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Jane Austen’s Emma. When Emma finds that she is deeply misled in her beliefs about the other characters in her story, Mr. Knightly helps her to learn the truth and the story comes to a happy ending (p. 6). Hamlet, by contrast, finds no pat answers to his questions; rival interpretations remain throughout the play, so that directors who would stage the play have to impose their own interpretations on the script (p. 5). MacIntyre notes, “Philosophers have customarily been Emmas and not Hamlets” (p. 6); that is, philosophers have treated their conclusions as accomplished truths, rather than as “more adequate narratives” (p. 7) that remain open to further improvement.

The second point of EC addresses the relationship between narratives, truth, and education. The traditional education of children begins in myth, and as children mature they learn to distinguish the lessons of these stories from the fictional events, the truths from the myths. In the course of this education, however, the student grows to respect the myths as bearers of truth. The student who grows through this kind of education to become a scholar “may become . . . a Vico or a Hamann” (p. 8. Johann Georg Hamaan (1730-1788), Giambattista Vico (1668-1744)). Another approach to education is the method of Descartes, who begins by rejecting everything that is not clearly and distinctly true as unreliable and false in order to rebuild his understanding of the world on a foundation of undeniable truth.

Ironically, in the process of rejecting myth, Descartes creates a narrative that is not only mythical but profoundly false. Rather than identifying specific areas of crisis in which he had lost confidence in his understanding of the world and situating himself within the tradition that has formed his understanding and his enquiry, Descartes presents himself as willfully rejecting everything he had believed, and ignores his obvious debts to the Scholastic tradition, even as he argues his case in French and Latin. For MacIntyre, seeking epistemological certainty through universal doubt as a precondition for enquiry is a mistake: “it is an invitation not to philosophy but to mental breakdown, or rather to philosophy as a means of mental breakdown.” David Hume’s cry of pain in his Treatise of Human Nature is the outcome of this kind of philosophical practice (EC, pp. 10-11). MacIntyre contrasts Descartes’ descent into mythical isolation with Galileo, who was able to make progress in astronomy and physics by struggling with the apparently insoluble questions of late medieval astronomy and physics, and radically reinterpreting the issues that constituted those questions.

To make progress in philosophy one must sort through the narratives that inform one’s understanding, struggle with the questions that those narratives raise, and on occasion, reject, replace, or reinterpret portions of those narratives and propose those changes to the rest of one’s community for assessment. Human enquiry is always situated within the history and life of a community. There is no alternative ahistorical, non-traditional way to make progress in human enquiry. MacIntyre returns to this theme in WJWR (chapters 17, 18, 19), in 3RV, and in his Aquinas Lecture, “First Principles, Final Ends, and Contemporary Philosophical Issues” (1990).

The third point of EC is that we can learn about progress in philosophy from the philosophy of science. In particular, “Kuhn’s work criticized provides an illuminating application for the ideas which I have been defending” (EC, p. 15) Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions had argued that scientists practice normal science according to the norms of paradigms or “disciplinary matrices.” Scientific revolutions occur when scientists abandon one paradigm for another. Kuhn’s “paradigm shifts,” however, are unlike MacIntyre’s resolutions of epistemological crises in two ways. First they are not rational responses to specific problems. Kuhn compares paradigm shifts to religious conversions (pp. 150, 151, 158), stressing that they are not guided by rational norms and he claims that the “mopping up” phase of a paradigm shift is a matter of convention in the training of new scientists and attrition among the holdouts of the previous paradigm (Kuhn, pp. 152, 159). Second, the new paradigm is treated as a closed system of belief that regulates a new period of “normal science”; Kuhn’s revolutionary scientists are Emmas, not Hamlets.

MacIntyre takes Kuhn’s position as a restatement of Michael Polyani’s theory that “reason operates only within traditions and communities,” so that transitions between traditions or reconstructions of failed traditions must be irrational (EC, p. 16). On Kuhn’s account, “scientific revolutions are epistemological crises understood in a Cartesian way. Everything is put in question simultaneously” (EC, p. 17).

MacIntyre proposes elements of Imre Lakatos’ philosophy of science as correctives to Kuhn’s. While Lakatos has his own shortcomings, his general account of the methodologies of scientific research programs recognizes the role of reason in the transitions between theories and between research programs (Lakatos’ analog to Kuhn’s paradigms or disciplinary matrices). Lakatos presents science as an open ended enquiry, in which every theory may eventually be replaced by more adequate theories. For Lakatos, unlike Kuhn, rational scientific progress occurs when a new theory can account both for the apparent promise and for the actual failure of the theory it replaces. The third conclusion of MacIntyre’s essay is that decisions to support some theories over others may be justified rationally to the extent that those theories allow us to understand our experience and our history, including the history of the failures of inadequate theories. EC answers the question that arose from ASIA of how to proceed philosophically. All of MacIntyre’s mature work uses and develops the methodology presented in this essay.

4. Major works since 1977

a. After Virtue

AV (1981, 2nd ed. 1984, 3rd ed. 2007) applies the methodology of EC to many of the same issues addressed in ASIA and in SHE, but interprets the history of ethics and the failure of modern moral philosophy in Aristotelian terms. For Aristotle, moral philosophy is a study of practical reasoning, and the excellences or virtues that Aristotle recommends in the Nicomachean Ethics are the intellectual and moral excellences that make a moral agent effective as an independent practical reasoner. AV criticizes modern liberal individualism and scientific determinism for separating practical reasoning from morality and political life; it proposes instead a return to Aristotelian ethics and politics.

i. Critical Argument of AV

The critical argument of AV, which makes up the first half of the book, begins by examining the current condition of secular moral and political discourse. MacIntyre finds contending parties defending their decisions by appealing to abstract moral principles, but he finds their appeals eclectic, inconsistent, and incoherent. MacIntyre also finds that the contending parties have little interest in the rational justification of the principles they use. The language of moral philosophy has become a kind of moral rhetoric to be used to manipulate others in defense of the arbitrary choices of its users. What Stevenson had said incorrectly about the meaning of moral judgments has come to be true of the use of moral judgments. MacIntyre reinterprets “emotivism,” Stevenson’s “false theory of meaning” as a “cogent theory of use,” and he names the culture that uses moral rhetoric pragmatically and syncretically “the culture of emotivism.”

MacIntyre traces the lineage of the culture of emotivism to the secularized Protestant cultures of northern Europe (AV, p. 37). These cultures had abandoned any connection between an agent’s natural telos, personal desires, or pursuit of goods and that same agent’s moral duties when they had adopted the divine command moralities of fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth century Christian moral theology. The secular moral philosophers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shared strong and extensive agreements about the content of morality (AV, p. 51) and believed that their moral philosophy could justify the demands of their morality rationally, free from religious authority.

Modern moral philosophy had thus set for itself an incoherent goal. It was to vindicate both the moral autonomy of the individual and the objectivity, necessity, and categorical character of the rules of morality (AV, p. 62). MacIntyre surveys the best efforts to achieve the goals of modern moral philosophy but dismisses each one as a moral fiction.

Given the failure of modern moral philosophy, MacIntyre turns to an apparent alternative, the pragmatic expertise of professional managers. Managers are expected to appeal to the facts to make their decisions on the objective basis of effectiveness, and their authority to do this is based on their knowledge of the social sciences. An examination of the social sciences reveals, however, that many of the facts to which managers appeal depend on sociological theories that lack scientific status. Thus, the predictions and demands of bureaucratic managers are no less liable to ideological manipulation than the determinations of modern moral philosophers.

If modern morality has been revealed to be “a theater of illusions,” then we must reject it, and this rejection can take two forms. Either we follow Nietzsche and defend the autonomy of the individual against the arbitrary demands of conventional moral reasoning, or we reject both moral autonomy and arbitrary conventional moral reasoning to follow Aristotle and investigate practical reason and the role of moral formation in preparing the human agent to succeed as an independent practical reasoner.

The critical argument of AV raises serious questions about the rational justification of modern moral philosophy, and it also proposes an explanation for the rational failure of modern moral philosophy: Modern moral philosophy separates moral reasoning about duties and obligations from practical reasoning about ends and practical deliberation about the means to one’s ends, and in doing so it separates morality from practice. Kant separates moral and practical reasoning explicitly in The Critique of Pure Reason (Critique of Pure Reason, A800/B828–A819/B847) and in The Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals (First Section, pp. 393-405.); Mill makes the same separation in Utilitarianism (chapter 2).

MacIntyre compares the separation of morality from practice or the separation of moral reasoning from practical reasoning in modern moral philosophy to the separation of morality from practice in Polynesian taboo. The Polynesians had lost the practical justifications for their well-established moral customs by the time they first made contact with European explorers; so when they told these visitors that certain practices were forbidden because those practices were “taboo,” they were unable to explain why these practices were forbidden or what, precisely, “taboo” meant. Many Europeans also lost the practical justifications for their moral norms as they approached modernity; for these Europeans, claiming that certain practices are “immoral,” and invoking Kant’s categorical imperative or Mill’s principle of utility to explain why those practices are immoral, seems no more adequate than the Polynesian appeal to taboo. The comparison between modern morality and taboo is a recurring theme in MacIntyre’s ethical work.

MacIntyre’s critique of the separation of morality from practice also draws on his criticism of determinist social science. Practice involves free and deliberate human action, while morality divorced from practice regulates only outward human behavior. Determinist social scientists, notably Stalinists but also behaviorists like W.V. Quine, viewed human behaviors as determined responses to various kinds of causal factors, and refused to examine the things people do in terms of “intentions, purposes, and reasons for action” (Quine, quoted in AV, p. 83). Instead, determinist social scientists sought “law-like generalizations” about the connections of these causes to their behavioral effects, which would enable them to predict human behavior, and bring scientific understanding to the work of organizational management (AV, pp. 88–91).

ii. The Constructive Argument of AV

In the second half of AV, MacIntyre explores the moral tradition that examines human judgment, human weakness, and excellence in human action. The constructive argument of the second half of the book begins with traditional accounts of the excellences or virtues of practical reasoning and practical rationality rather than virtues of moral reasoning or morality. These traditional accounts define virtue as arête, as excellence, and all of the definitions offered in the second half of AV describe the excellence of the human agent who judges well and acts effectively in pursuit of desired ends. MacIntyre sifts these definitions and then gives his own definition of virtue, as excellence in human agency, in terms of practices, whole human lives, and traditions in chapters 14 and 15 of AV.

In the most often quoted sentence of AV, MacIntyre defines a practice as (1) a complex social activity that (2) enables participants to gain goods internal to the practice. (3) Participants achieve excellence in practices by gaining the internal goods. When participants achieve excellence, (4) the social understandings of excellence in the practice, of the goods of the practice, and of the possibility of achieving excellence in the practice “are systematically extended” (AV, p. 187).

Practices, like chess, medicine, architecture, mechanical engineering, football, or politics, offer their practitioners a variety of goods both internal and external to these practices. The goods internal to practices include forms of understanding or physical abilities that can be acquired only by pursuing excellence in the associated practice. Goods external to practices include wealth, fame, prestige, and power; there are many ways to gain these external goods. They can be earned or purchased, either honestly or through deception; thus the pursuit of these external goods may conflict with the pursuit of the goods internal to practices.

MacIntyre illustrates the conflict between the pursuits of internal and external goods in the parable of the chess playing child. An intelligent child is given the opportunity to win candy by learning to play chess. As long as the child plays chess only to win candy, he has every reason to cheat if by doing so he can win more candy. If the child begins to desire and pursue the goods internal to chess, however, cheating becomes irrational, because it is impossible to gain the goods internal to chess or any other practice except through an honest pursuit of excellence. Goods external to practices may nevertheless remain tempting to the practitioner.

Practices are supported by institutions like chess clubs, hospitals, universities, industrial corporations, sports leagues, and political organizations. Practices exist in tension with these institutions, since the institutions tend to be oriented to goods external to practices. Universities, hospitals, and scholarly societies may value prestige, profitability, or relations with political interest groups above excellence in the practices they are said to support.

Personal desires and institutional pressures to pursue external goods may threaten to derail practitioners’ pursuits of the goods internal to practices. MacIntyre defines virtue initially as the quality of character that enables an agent to overcome these temptations: “A virtue is an acquired human quality the possession and exercise of which tends to enable us to achieve those goods which are internal to practices and the lack of which effectively prevents us from achieving any such goods” (AV, p. 191).

MacIntyre finds that this first level definition is inadequate to describe an excellent human agent. It is not enough to be an excellent navigator, physician, or builder; the excellent human agent lives an excellent life. Excellence as a human agent cannot be reduced to excellence in a particular practice (See AV, pp. 204–205, and Ethics and Politics, pp. 196–7). MacIntyre therefore adds a second level to his definition of virtue.

The virtues therefore are to be understood as those dispositions which will not only sustain practices and enable us to achieve the goods internal to practices, but which will also sustain us in the relevant kind of quest for the good, by enabling us to overcome the harms, dangers, temptations, and distractions which we encounter, and which will furnish us with increasing self-knowledge and increasing knowledge of the good (AV, p. 219).

The excellent human agent has the moral qualities to seek what is good and best both in practices and in life as a whole.

The second level definition is still inadequate, however, because it does not take into account the individual’s response to the life and legacy of her or his community. MacIntyre rejects individualism and insists that we view human beings as members of communities who bear specific debts and responsibilities because of our social identities. The responsibilities one may inherit as a member of a community include debts to one’s forbearers that one can only repay to people in the present and future. These responsibilities also include debts incurred by the unjust actions of ones’ predecessors.

MacIntyre acknowledges that contemporary individualism insists that “the self is detachable from its social and historical roles and statuses” (AV, p. 221), but he illustrates his counterpoint point with three national communities in which contemporary citizens continue to bear the debts of their predecessors. The enslavement and oppression of black Americans, the subjugation of Ireland, and the genocide of the Jews in Europe remained quite relevant to the responsibilities of citizens of the United States, England, and Germany in 1981, as they still do today. Thus an American who said “I never owned any slaves,” “the Englishman who says ‘I never did any wrong to Ireland,’” or “the young German who believes that being born after 1945 means that what Nazis did to Jews has no moral relevance to his relationship to his Jewish contemporaries” all exhibit a kind of intellectual and moral failure. “I am born with a past, and to cut myself off from that past in the individualist mode, is to deform my present relationships” (p. 221). For MacIntyre, there is no moral identity for the abstract individual; “The self has to find its moral identity in and through its membership in communities” (p. 221).

Since MacIntyre finds social identity necessary for the individual, MacIntyre’s definition of the excellence or virtue of the human agent needs a social dimension:

The virtues find their point and purpose not only in sustaining those relationships necessary if the variety of goods internal to practices are to be achieved and not only in sustaining the form of an individual life in which that individual may seek out his or her good as the good of his or her whole life, but also in sustaining those traditions which provide both practices and individual lives with their necessary historical context (AV, p. 223).

This third, social, level completes MacIntyre’s account of the excellence of the human agent in AV.

iii. Aristotelian Critique of Modern Ethics and Politics

The remaining chapters of AV contrast MacIntyre’s Aristotelian notion of the virtues as excellences of character from modern notions of virtue as the quality of a person who obeys moral rules. These chapters also lay out some of the practical implications of MacIntyre’s Aristotelian project for contemporary ethics and politics. The loss of teleology makes morality appear arbitrary (AV, p. 236), separates moral reason from practical and political reasoning (AV, p. 236), and removes the notion of what one deserves from modern notions of justice (AV, p. 249). MacIntyre concludes that “modern systematic politics . . . expresses in its institutional forms a systematic rejection” of the Aristotelian tradition of the virtues and therefore “has to be rejected” by those who commit themselves to the tradition of the virtues (AV, p. 255). In other words, those who approach moral and political philosophy in terms of the development of the human agent and the advancement of practical reasoning in the context of the life of a community cannot succeed in their task if they compromise their work by committing themselves to the arbitrary goals, methods, and language of modern politics.

At the end of the argument of AV, MacIntyre returns to the ultimatum of chapter 10, “Nietzsche or Aristotle.” Where Nietzsche intended his work as a critique of modern morality, Nietzsche in fact becomes the ultimate embodiment of the moral isolation and arbitrariness of modern liberal individualism. This fault remains invisible from a modern viewpoint, but when viewed from the perspective of the Aristotelian tradition of the virtues, it is quite clear (AV, pp. 258-259).

Since “goods, and with them the only grounds for the authority of laws and virtues, can only be discovered by entering into those relationships which constitute communities whose central bond is a shared vision of and understanding of goods” (AV, p. 258), any hope for the transformation and renewal of society depends on the development and maintenance of such communities. Revolution cannot be imposed (AV, p. 238), although it may be cultivated. To wait “for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict,” is to await a person who can unify communities that encourage moral formation in judgment and action.

iv. Criticism of AV

MacIntyre’s Aristotelian approach to ethics as a study of human action distinguishes him from post-Kantian moral philosophers who approach ethics as a means of determining the demands of objective, impersonal, universal morality. This modern approach may be described as moral epistemology. Modern moral philosophy pretends to free the individual to determine for her- or himself what she or he must do in a given situation, irrespective of her or his own desires; it pretends to give knowledge of universal moral laws. MacIntyre rejects modern ethical theories as deceptive and self-deceiving masks for conventional morality and for arbitrary interventions against traditions. For MacIntyre, the freedom of self-determination is the freedom to recognize and pursue one’s good, and moral philosophy liberates the agent, in part, by helping the human agent to desire what is good and best, and to choose what is good and best.

MacIntyre’s ethics of human action also distinguishes his later Thomistic work from the efforts of some twentieth-century neo-Thomists to craft a moral epistemology out of Thomas Aquinas’s metaphysics and natural law. AV argues that an Aristotelian ethics of virtue may remain possible, without appealing to Aristotle’s metaphysics of nature. This claim remains controversial for two different, but closely related reasons.

Many of those who rejected MacIntyre’s turn to Aristotle define “virtue” primarily along moral lines, as obedience to law or adherence to some kind of natural norm. For these critics, “virtuous” appears synonymous with “morally correct;” their resistance to MacIntyre’s appeal to virtue stems from their difficulties either with what they take to be the shortcomings of MacIntyre’s account of moral correctness or with the notion of moral correctness altogether. Thus one group of critics rejects MacIntyre’s Aristotelianism because they hold that any Aristotelian account of the virtues must first account for the truth about virtue in terms of Aristotle’s philosophy of nature, which MacIntyre had dismissed in AV as “metaphysical biology” (AV, pp. 162, 179). Aristotelian metaphysicians, particularly Thomists who define virtue in terms of the perfection of nature, rejected MacIntyre’s contention that an adequate Aristotelian account of virtue as excellence in practical reasoning and human action need not appeal to Aristotelian metaphysics. Another group of critics, including materialists, dismissed MacIntyre’s attempt to recover an Aristotelian account of the virtues because they took those virtues to presuppose an indefensible metaphysical doctrine of nature.

A few years after the publication of AV, MacIntyre became a Thomist and accepted that the teleology of human action flowed from a metaphysical foundation in the nature of the human person (WJWR, ch. 10; AV, 3rd ed., p. xi). Nonetheless, MacIntyre has the main points of his ethics and politics of human action have remained the same. MacIntyre continues to argue toward an Aristotelian account of practical reasoning through the investigation of practice. Even though he has accepted Thomistic metaphysics, he seldom argues from metaphysical premises, and when pressed to explain the metaphysical foundations of his ethics, he has demurred. MacIntyre continues to argue from the experience of practical reasoning to the demands of moral education. MacIntyre’s work in WJWR, DRA, The Tasks of Philosophy, Ethics and Politics, and God, Philosophy, University continue to exemplify the phenomenological approach to moral education that MacIntyre took in After Virtue.

Contemporary scholars have defended MacIntyre’s unconventional Aristotelianism by challenging the conventions that MacIntyre is said to violate. Christopher Stephen Lutz examined some of the reasons for rejecting “Aristotle’s metaphysical biology” and assessed the compatibility of MacIntyre’s philosophy with that of Thomas Aquinas in Tradition in the Ethics of Alasdair MacIntyre (2004, pp. 133-140). Kelvin Knight took a broader approach in Aristotelian Philosophy: Ethics and Politics from Aristotle to MacIntyre (2007). Knight examined the ethics and politics of human action found in Aristotle and traced the development of that project through medieval and modern thought to MacIntyre. Knight distinguishes Aristotle’s ethics of human action from his metaphysics and shows how it is possible for MacIntyre to retrieve Aristotle’s ethics of human action without first defending Aristotle’s metaphysical account of nature.

b. Two Books on Rationality: WJWR and 3RV

For MacIntyre, “rationality” comprises all the intellectual resources, both formal and substantive, that we use to judge truth and falsity in propositions, and to determine choice-worthiness in courses of action. Rationality in this sense is not universal; it differs from community to community and from person to person, and may both develop and regress over the course of a person’s life or a community’s history. MacIntyre describes this culturally relative, even subjective characteristic of rationality in the first chapter of WJWR (1988):

So rationality itself, whether theoretical or practical, is a concept with a history: indeed, since there are also a diversity of traditions of enquiry, with histories, there are, so it will turn out, rationalities rather than rationality, just as it will also turn out that there are justices rather than justice (WJWR, p. 9).

Rationality is the collection of theories, beliefs, principles, and facts that the human subject uses to judge the world, and a person’s rationality is, to a large extent, the product of that person’s education and moral formation.

To the extent that a person accepts what is handed down from the moral and intellectual traditions of her or his community in learning to judge truth and falsity, good and evil, that person’s rationality is “tradition-constituted.” Tradition-constituted rationality provides the schemata by which we interpret, understand, and judge the world we live in. The apparent reasonableness of mythical explanations, religious doctrines, scientific theories, and the conflicting demands of the world’s moral codes all depend on the tradition-constituted rationalities of those who judge them. For this reason, some of MacIntyre’s critics have argued that tradition-constituted rationality entails an absolute relativism in philosophy.

The apparent problem of relativism in MacIntyre’s theory of rationality is much like the problem of relativism in the philosophy of science. Scientific claims develop within larger theoretical frameworks, so that the apparent truth of a scientific claim depends on one’s judgment of the larger framework. The resolution of the problem of relativism therefore appears to hang on the possibility of judging frameworks or rationalities, or judging between frameworks or rationalities from a position that does not presuppose the truth of the framework or rationality, but no such theoretical standpoint is humanly possible. Nonetheless, MacIntyre finds that the world itself provides the criterion for the testing of rationalities, and he finds that there is no criterion except the world itself that can stand as the measure of the truth of any philosophical theory. So MacIntyre balances the relativity of rationality against the objectivity of the world that we investigate. As Popper and Lakatos found in the philosophy of science, MacIntyre concludes that experience can falsify theory, releasing people from the apparent authority of traditional rationalities.

MacIntyre holds that the rationality of individuals is not only tradition-constituted, it is also tradition constitutive, as individuals make their own contributions to their own rationality, and to the rationalities of their communities. Rationality is not fixed, within either the history of a community or the life of a person. Unexplainable events can occur that reveal shortcomings in a person’s rational resources, like the anomalous data that precipitate scientific revolutions in Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions or demand changes in research programmes in Imre Lakatos’ The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. Problems exposed by anomalous data or by conflicts with other traditions, other communities, or other people may prove rationally insoluble under the constraints that a given tradition places on rationality. Such events, when fully recognized, demand creative solutions, and it may happen that some person or group will discover what appears to be a more adequate response to those problems. To the extent that these new solutions are adopted by others and passed on to subsequent generations (for better or for worse), the rationality of those responsible for the new approach becomes “tradition-constitutive.”

The possibility that experience may falsify theory distinguishes MacIntyre’s theory of tradition-constituted and tradition-constitutive rationality from forms of relativism that make rationality entirely tradition-dependent or entirely subjective. Nonetheless, MacIntyre denies that such falsification is common (WJWR, chs. 18 and 19), and history shows us that individuals, communities, and even whole nations may commit themselves militantly over long periods of their histories to doctrines that their ideological adversaries find irrational. This qualified relativism of appearances has troublesome implications for anyone who believes that philosophical enquiry can easily provide certain knowledge of the world. According to MacIntyre, theories govern the ways that we interpret the world and no theory is ever more than “the best standards so far” (3RV, p. 65). Our theories always remain open to improvement, and when our theories change, the appearances of our world—the apparent truths of claims judged within those theoretical frameworks—change with them.

From the subjective standpoint of the human enquirer, MacIntyre finds that theories, concepts, and facts all have histories, and they are all liable to change—for better or for worse. MacIntyre’s philosophy offers a decisive refutation of modern epistemology, even as it maintains philosophy is a quest for truth. MacIntyre’s philosophy is indebted to the philosophy of science, which recognizes the historicism of scientific enquiry even as it seeks a truthful understanding of the world. MacIntyre’s philosophy does not offer a priori certainty about any theory or principle; it examines the ways in which reflection upon experience supports, challenges, or falsifies theories that have appeared to be the best theories so far to the people who have accepted them so far. MacIntyre’s ideal enquirers remain Hamlets, not Emmas.

i. Whose Justice? Which Rationality?

WJWR presents MacIntyre’s most thorough argument for his theory of rationality. He summarizes the main points of his theory in chapter 1. In chapters 2 through 16, MacIntyre follows the progress of the Western tradition through “three distinct traditions:” from Homer and Aristotle to Thomas Aquinas, from Augustine to Thomas Aquinas and from Augustine through Calvin to Hume (WJWR, p. 326). The inhabitants of these traditions work to deepen, correct, and extend the claims and theories of their predecessors. Chapter 17 examines the modern liberal denial of tradition, and the ironic transformation of liberalism into the fourth tradition to be treated in the book. Chapter 18 reviews MacIntyre’s claims and conclusions concerning the tradition-constituted nature and tradition-constitutive power of human rationality. Chapters 19 and 20 explore the consequences of MacIntyre’s theory for conflicts between traditions.

WJWR fulfills a promise made at the end of AV: “I promised a book in which I should attempt to say both what makes it rational to act in one way rather than another and what makes it rational to advance and defend one conception of practical rationality rather than another. Here it is” (p. 9). To fulfill this promise, MacIntyre opens the book by arguing that “the Enlightenment made us . . . blind to . . . a conception of rational enquiry as embodied in a tradition, a conception according to which the standards of rational justification themselves emerge from and are part of a history.” From the standpoint of human enquiry, no group can arrogate to itself the authority to guide everyone else toward the good. We can only struggle together in our quests for justice and truth and each community consequently frames and revises its own standards of justice and rationality. MacIntyre concludes that neither reason nor justice is universal: “since there are a diversity of traditions of enquiry, with histories, there are, so it will turn out, rationalities rather than rationality, just as it will also turn out that there are justices rather than justice” (p. 9).

The thesis that rationalities and justices arise from the histories and traditions of communities sets MacIntyre squarely at odds with all modern philosophy, and particularly with the unacknowledged imperialism of any form of metaethics that would offer a neutral, third-party forum in which to adjudicate the practical differences between contending moral traditions by the peculiar standards of modern liberal individualism. The same thesis also appears to set MacIntyre at odds with the traditions of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas—traditions he claims to accept and defend—which make unambiguous claims about the universal nature, true reason, and objective justice. The book therefore has two tasks. On the one hand, the book relates the histories of particular rationalities and justices in a way that undermines the abstract universal notions of reason and justice that provide the foundations for modern moral and political thought. On the other hand, the book provides prima facie evidence

that those who have thought their way through the topics of justice and practical rationality, from the standpoint constructed by and in the direction pointed out first by Aristotle and then by Aquinas, have every reason at least so far to hold that the rationality of their tradition has been confirmed by its encounters with other traditions (p. 403).

In short, the book offers an internal critique of modernity, arguing that it is incoherent by its own standards, and it offers an internal justification of Thomism, holding that Thomism is rationally justified, for Thomists, by Thomist standards. Contrary to initial expectations, MacIntyre’s historicist, particularist critique of modernity is compatible with the historically situated Thomist tradition.