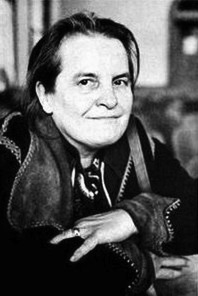

Cornelius Castoriadis (1922—1997)

Cornelius Castoriadis was an important intellectual figure in France for many decades, beginning in the late-1940s. Trained in philosophy, Castoriadis also worked as a practicing economist and psychologist while authoring over twenty major works and numerous articles spanning many traditional philosophical subjects, including politics, economics, psychology, anthropology, and ontology. His oeuvre can be understood broadly as a reflection on the concept of creativity and its implications in various fields. Perhaps most importantly he warned of the dangerous political and ethical consequences of a contemporary world that has lost sight of autonomy, i.e. of the need to set limits or laws for oneself.

Cornelius Castoriadis was an important intellectual figure in France for many decades, beginning in the late-1940s. Trained in philosophy, Castoriadis also worked as a practicing economist and psychologist while authoring over twenty major works and numerous articles spanning many traditional philosophical subjects, including politics, economics, psychology, anthropology, and ontology. His oeuvre can be understood broadly as a reflection on the concept of creativity and its implications in various fields. Perhaps most importantly he warned of the dangerous political and ethical consequences of a contemporary world that has lost sight of autonomy, i.e. of the need to set limits or laws for oneself.

Influenced by his understanding and criticism of traditional philosophical figures such as the Ancient Greeks, German Idealists, Marx, and Heidegger, Castoriadis was also influenced by thinkers as diverse as Sigmund Freud, Max Weber, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Georg Cantor. He engaged in dynamic intellectual relationships with his fellow members of Socialisme ou Barbarie (including Claude Lefort and Jean-François Lyotard, among others) and later in life with leading figures in mathematics, biology, and other fields. He is remembered largely for his initial support for and subsequent break from Marxism, for his call for Western thought to embrace the reality of creativity, and finally for his defense of an ethics and politics based on “lucid” deliberation and social and individual autonomy. For Castoriadis the central question of philosophy and the source of philosophy’s importance is its capacity to break through society’s closure and ask what the relevant questions for humans ought to be.

Table of Contents

- Beginnings

- The Break From Marxism

- Theoretical Developments

- The Project of Autonomy

- References and Further Reading

1. Beginnings

a. Youth in Greece and Arrival in France

Cornelius Castoriadis was born to an ethnically Greek family living in Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1922. The year was one of the most tumultuous in modern Greek history. Following the First World War, lands granted to Greece at the expense of the Ottoman Empire by the victorious Entente powers were being claimed militarily by Turkish nationalists. As the defeat of the Greek army in the formerly Ottoman territories seemed imminent, Castoriadis’s father relocated the family to Athens, the home of Castoriadis’s mother, when Cornelius was a few months old. As a result, Castoriadis spent his youth in Athens where he discovered philosophy at the age of twelve or thirteen. He engaged in communist youth activities while in high school and later studied economics, political science, and law while resisting the Axis occupation of Greece during Second World War. His Trotskyist opposition group distanced itself from the pro-Stalinist opposition. During this time Castoriadis published his first academic writings on Max Weber’s methodology and led seminars on philosophers including Kant and Hegel. In 1945 he won and accepted a scholarship to write a philosophy dissertation at the Sorbonne in Paris, thus starting a wholly new stage in his life.

In Paris Castoriadis planned to write his dissertation on the impossibility of a closed, rationalist philosophical system. This plan took second stage, however, to his critical-political activities. He became active in the French branch of the Trotskyist party though he quickly criticized the group’s failure to take a stronger stance against Stalin. By 1947 Castoriadis developed his own criticism of the Soviets who, he argued, had only created a new brand of exploitation in Russia, i.e. bureaucratic exploitation (Castoriadis Reader 3). Discovering he shared similar views with recent acquaintance Claude Lefort, the two began to distance themselves altogether from the Trotskyist goal of party rule.

Castoriadis began two major vocations in 1948. First, he and Lefort co-founded the journal and political group Socialisme ou Barbarie (Socialism or Barbarism). They focused on criticizing both Soviet bureaucracy and capitalism and on developing ideas for other possible organizations of society. The group’s founding statement expressed an interest in a non-dogmatic yet still Marxist social critique. On the one hand, the traditional questions Marx raised about workers and social organization would remain important, while on the other hand any commitment to specific Marxist positions would remain conditional. Despite internal dissent and membership changes, the group remained partially intact from 1948 to 1966 with a peak involvement of a few dozen members and approximately 1,000 copies produced per issue of the group’s journal. Castoriadis’s leadership and writings helped establish him as an important figure in the political-intellectual field in Paris.

Second, in 1948 Castoriadis began working as an economist with the international Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC). He would remain there until 1970, analyzing the short- and medium-term economic status of developed nations. His work with OEEC not only allowed him an income and the possibility of remaining in France until his eventual nationalization, but it also permitted him great insights into the economies of capitalist countries and into the functioning of a major bureaucratic organization. Following his employment with OEEC, Castoriadis worked during the 1970s as a psychoanalyst. He finally received an academic position at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris in 1979. He remained with EHESS until his death following heart surgery in 1997.

b. The Concept of Self-Management in the Early Writings

Reflecting on the Socialisme ou Barbarie group, Castoriadis considered one of his and the journal’s most important contributions to be the concept of workers’ self-management (Castoriadis Reader 1-17). While in his later writings the concept would develop into a theory of autonomy standing independently of the Marxist framework, during the journal years the theory of self-management served as a modification of or an alternative to Marx’s theory of class struggle.

In 1955’s “On the Content of Socialism” (Castoriadis Reader 40-105) Castoriadis, writing under a pseudonym in order to protect himself from deportation as an alien, defined the central conflict of society not in terms of the classical dichotomy between owners and workers but in terms of a conflict between directors and executants. (Notably, this distinction coincides with Aristotle’s definitions of master and slave in the Politics and with philosopher Simone Weil’s economic analysis from as early as 1933). Contemporary society, he argued, is split between a stratum of managers who direct workers, and a stratum of workers obedient to managers. Workers pass real-world information up to the managers; but they must then carry out the often nonsensical orders that are passed back down. For Castoriadis, in both Western and so-called “communist” countries (i.e. countries Castoriadis would have said embodied only a semblance of communism) managers are often uninformed about subordinate tasks, know little about interrelated fields of work, and nevertheless they still direct the immediate production process. Such a managerial apparatus, argued Castoriadis, leads to inefficiency, waste, and unnecessary conflict between aloof managers and servile workers.

The domination of society by the managerial apparatus can only be surpassed, argued Castoriadis, when workers take responsibility for organizing themselves. Workers must assume effective management of their own work situation in “full knowledge of the relevant facts.” This emphasis on the importance of knowledge implies that individuals should work cooperatively. They should form workers councils consisting of conditionally elected members. Those members, in a strict reversal of the bureaucratic managerial model, should convene frequently not in order to make decisions for workers but in order to express the decisions of the workers. They should then convey important information back to the workers for the purpose of helping workers make their own decisions. In this way, the workers’ council is not a managerial stratum. Rather, it helps convey information to workers for their purposes. While Castoriadis did support a centralized institution, or assembly of councils, capable of making rapid decisions when needed, such decisions, he argued, would be at all times reversible by the workers and their councils.

In the end, Castoriadis contrasted self-management with individualistic, negative libertarian, or anarchic ideals, i.e. the ideals idolized in capitalist countries. Such countries reject the role of workers councils but they then become heavily bureaucratized anyway. Castoriadis also contrasted self-management with the explicitly centralized, exploitative bureaucracies of the so-called communist countries. In both cases what currently blocks the emergence of self-management is the division between directors and executants. While some specialization of labor will always be necessary, what is damaging today is specifically the dominance of a class that is devoted only to the management of other people’s work.

2. The Break From Marxism

Like many anti-totalitarian leftists, Castoriadis initially tried to divorce the bad features of twentieth-century communism from the “true meaning” of Marxism. However, by the mid- to late-1950s he came to argue that a profound critique of existing communist countries also requires a critique of Marx’s philosophy. Capitalism, Marxism, and the Soviet experiment were all based in a common set of presuppositions.

Castoriadis’s analysis of the institutional structure of the Soviet Union, collected later in La Société Bureaucratique (Bureaucratic Society), suggested that the Soviet Union is dominated by a militaristic, bureaucratic institution that Castoriadis called total bureaucratic capitalism (TBC). This name implies that the principle of the social order in the USSR is truly an analogue—albeit a more centralized analogue—of the Western capitalist order, which Castoriadis called fragmented bureaucratic capitalism (FBC) (Castoriadis Reader 218-238). Castoriadis then argued that both TBC and FBC were rooted in a common “social imaginary.”

This social imaginary, common to TBC and FBC, was expressed as a desire for rational mastery over self and nature. Both capitalist thought and Marx assumed that capital has enormous, even total power over humanity. This assumption led to an excessive desire on both sides to control its supposed force. For this reason Marx’s followers aimed to create a totalitarian bureaucratic system that could theoretically gain “mastery over the master” (World in Fragments 32-43). Yet, according to Castoriadis’s analysis, the exploitation found in Western society was not solved by this system of control; it was instead rendered more total and crushing. The managerial, bureaucratic class became a unified, oppressive force in itself, pursuing its own interests against the people. Hence, Castoriadis concluded that the eventual efforts of the communist countries to gain rational mastery were not truly separable from Marx’s own, earlier philosophy. That philosophy itself had emerged from the common social imaginary that FBC and TBC share, namely the desire to gain total control of nature and history through controlling capital.

Castoriadis also developed more specific criticisms of Marx’s economic assumptions. Indeed, as early as 1959’s “Modern Capitalism and Revolution” (Political and Social Writings II 226-315) he attacked Marx’s method of treating workers as though they were cogs in the machine of capitalism. Marx, he argued, failed to consider the importance of the unplanned, contingent actions of the proletariat, actions powerful enough to save a company from mismanagement or to lead it into disaster. In other words, Marx’s analysis of capitalism was too deterministic. The creative decisions of workers are not strictly subject to capital’s laws. Rather, workers sustain or destroy capitalism itself through their own actions. As such, workers’ actions—singularly and collectively—can lead to changes in the very laws of the system.

As a result, Castoriadis found that Marx’s view of history was based in flawed assumptions. The actions of workers cannot be sufficiently explained by supposed laws of historical dialectic. Workers themselves could determine the law of history rather than being merely determined by history’s law. As such, the classical theory of capitalism’s inevitable collapse into socialism and then communism could not be sustained. While Castoriadis agreed with Marx (and praised Marx’s far-reaching analysis) that the history of capitalism is ridden with crises and so-called contradictions, he disagreed with Marx’s deduction of future historical developments from out of those events. The outcome of a capitalist crisis is in truth determined by how individuals and society take up those crises, not by any necessary, internal self-development of capitalism “itself.”

From out of this engagement with Marx, Castoriadis began to develop his own view of how autonomous society could arise. Autonomous society, he argued, is a creation of the singular individual and the collectivity. It cannot be sufficiently deduced or developed from tendencies, potentialities, impossibilities, or necessities contained within the current system. Whereas Marx interpreted the workers’ struggles for autonomy as part of the rational self-development of capitalism itself, Castoriadis, by contrast, emphasized the real contingency of the historical successes of democratic-emancipatory struggles. These struggles had preceded capitalism, were subdued within capitalism and the modern era of rational mastery, and are still present but also largely subdued in the contemporary age of FBC and TBC (World in Fragments 32-43). Castoriadis’s break with Marx is therefore his break with the desire to gain mastery over the supposedly all-powerful forces controlling humanity and history.

3. Theoretical Developments

Between the end of Socialisme ou Barbarie in 1966 and the publication of L’institution imaginaire de la société (The Imaginary Institution of Society) in 1975 the tenor and explicit subject matter of Castoriadis’s work changed noticeably. For the remainder of his life he engaged with a broader variety of disciplines, including psychoanalysis, biology, sociology, ecology, and mathematics. His specific views in each field were almost always linked to his general theory of the creative imagination—operating at both singular and collective levels—and to its implications for each discipline. Philosophy’s role, he argued, is to break through the closure of any instituted social imaginary in order to make possible a deliberative attitude about what humans ought actively to institute, i.e. about the very goals, ends, and capacities of society and individuals themselves. In this sense, Castoriadis’ ontology of creation makes possible his ethics and politics of autonomy (Section 4). In developing his theoretical concepts, Castoriadis never worked in a vacuum, as he contributed to several intellectual groups during this time, including the École Freudienne de Paris led by Jacques Lacan, the journal Textures (primarily philosophical), and the journal Libre (primarily political) with Claude Lefort.

a. The Creative Imagination

While the first division of L’institution imaginaire de la société offered a modified version of Castoriadis’ critique of Marx, the second division contained his full-scale theory of the creative imagination. He argued there that the imagination is not primarily a capacity to create visual images. Rather, it is the singular or collective capacity to create forms, i.e. the capacity to create the presentation or self-presentation of being itself. The theory of the creative imagination developed over many years through essays conversant with the Western intellectual tradition. In this section I will present his views as a dialogue with the figures to whom Castoriadis acknowledged a debt.

i. Philosophical Background: Aristotle

In 1978’s “The Discovery of the Imagination” (World in Fragments 213-245) Castoriadis distinguished what he called the radical imagination from the “traditional” view of the imagination. Aristotle’s traditional view, depicted in De Anima, treated the imagination as a faculty generating an image that accompanies sensations but typically distorts them. Since sensations themselves are always true according to Aristotle, the extra imaginary capacity (primarily serving to reproduce what the senses provided, to recombine past sensations into new images, or to supplement sensation confusingly) was treated mainly as an obfuscator of truth. Castoriadis argued that philosophy usually considered this account of imagination to reveal its basic power. Regardless of whether they attacked or praised it, philosophers tended to treat the imagination in this way as something that creates a kind of fantastical non-reality.

Despite this picture of the imagination as “negative,” Castoriadis argued that hidden deeper within the philosophical tradition was a discovery of a primary imagination that is not simply negative. Indeed, in De Anima 3.7-3.9 Aristotle argued that the primary imagination is a “condition for all thought.” For Castoriadis, this claim implies that there can be no grasp of reality without the primary imagination. It should be interpreted, Castoriadis argued, as a capacity for the very presentation of reality as such, a presentation required for any further understanding. In this way, the primary imagination precedes any re-presentation of reality.

Even so, Aristotle remained an ambiguous figure for Castoriadis. He had raised difficult problems for any account of imagination as strictly negative or re-presentational; but he also failed to draw out the full consequences of his discovery of the primary imagination. Most of his writings and most of traditional philosophy portray the imagination as mainly reproductive, negative, or obfuscatory.

ii. Philosophical Background: Kant

According to Castoriadis, Immanuel Kant rediscovered the importance of the imagination and gave philosophy a new awareness of its role (World in Fragments 246-272). In Critique of Pure Reason, Kant had allowed that the imagination is the capacity to present an object even without the presence of that object in sensible intuition. As such, he freed the imagination from the traditional role of merely following or accompanying the senses in an a posteriori function. For Kant, the imagination was already involved in the initial presentation of whatever may appear to the senses.

Like Aristotle, however, Kant was an ambiguous figure for Castoriadis. While Kant was aware of the imagination’s creativity and its vital role in presenting whatever can appear, he was also too quick to re-subordinate the imagination to the task of offering presentations that remain within the a priori, necessary, and stable structures (i.e. the categories and pure forms of intuition) inherent in the knowing mind. For example, while Kant allowed the imagination a role in a priori mathematical construction in intuition, he allowed that it works in this way only within the framework of the pre-established forms of intuitions themselves (that is, within the pre-set structures of space and of time). In short, the imagination remained bound to functioning in a pre-established field in Kant’s theoretical work (Castoriadis Reader 319-337). The same tendency, argued Castoriadis, found expression in Kant’s later work on the imagination in the Critique of Judgment (Philosophy, Politics, Autonomy 81-123).

Nevertheless, Castoriadis in some sense followed the Kantian view that an unknown X, other than the knowing subject, can “occasion” imaginary presentations. Castoriadis preferred, however, to invoke Fichte’s term Anstoß (shock) for the “encounter” with whatever occasions imaginary activity. With this shock, the imagination goes into operation generates a presentation for itself. It thereby brings something “other” into a relation with itself, forming the presentation of the other as what it is. While Fichte had suggested that the imagination in some sense gives itself this shock, Castoriadis denied that the question of the internality or externality of the shock was decidable. Thus he maintained that the imagination forms either itself or another something into a presentation by “leaning on” (Freud’s term is anaclasis) what is formable in whatever it forms. Something in what the imagination forms thus lends itself to formation by the imagination. While there can be no account of the nature of this formability without the imagination’s actual formation of the formable X, Castoriadis argued that his fact does not prove that there is nothing formable in itself, i.e. that there is nothing at all apart from the imagination’s activity.

Finally, Castoriadis took his Kant-inspired account even further. He argued that the imagination can in some cases create a presentation of reality by starting without any shock whatsoever. The imagination can create a presentation or form of reality without any conditioning shock (Castoriadis Reader 323-6). Thus, while there are inevitably some shocks for any psyche, the shock is not a necessary condition for the operation of the imagination.

Castoriadis argued that Kant had implicitly recognized the creativity of the imagination. Kant, however, tried hard to chain down the imagination to stable structures of thought and intuition. But Kant’s efforts in this direction merely indicated that he was deeply aware of a creativity that is not necessarily stable or bound to an a priori rule of operation. He recognized the primary imagination. Hence Kant, like Aristotle, is an ambiguous friend for Castoriadis.

iii. Philosophical Background: Post-Kantian Philosophy

Castoriadis’s response to Kant’s philosophy, at least in its negative aspects, is not entirely dissimilar to the responses given by post-Kantians such as the German Idealists, Nietzsche, and Heidegger. However, it differs in that it does not involve the monism implicit or explicit in modern idealism (Hegel) and materialism (Nietzsche, Marx). Indeed, perhaps more than any other thinker since Kant, and in opposition to the monistic tendencies of most of the post-Kantians, Castoriadis embraced the inevitability of the encounter with an “other.” There is no such thing as a singular substance existing radically alone; for each substance interacts with others. While Castoriadis’s views do at times overlap with the phenomenological tradition, his theory of radical creativity puts him at odds with the Heideggerian tradition. Castoriadis also diverged from the twentieth century “turn to language” in analytic philosophy (though he did develop a theory of signification in The Imaginary Institution of Society). More broadly, in contrast to prevalent cultural relativism of the twentieth century West, he instead expressed an absolute support for the project of moral and political autonomy (Section 4).

What is perhaps most vital for understanding Castoriadis’s creative imagination—what makes his project unique in contemporary philosophy—is that his analysis of creativity is not supposed to entail, by itself, a normative claim. Castoriadis does not assign a positive value to creativity as such. In fact, Castoriadis explicitly rejected the positive valuation of “the new for the sake of the new” (Post-Script on Insignificance 93-107). The endless search for the next thing or the newest idea in contemporary thought leads to a lack of understanding of the already established norms, and therefore to an unconscious redeployment of those norms. Even so, the radical creativity of the imagination does, in a different way, lead to value-theoretic considerations and, in particular, to a kind of politics. While value cannot be derived from being or creation, the very fact that being is creation leads to another question: What ought we create (or re-create), institute (or perpetuate), or set for ourselves as a project? How can we provide limits and institutions for ourselves so that we may effectively achieve and call into question what we understand to be good? As such, Castoriadis’s radical imagination might be said to “clear the way” for his politics and ethics (Section 4).

iv. Creation ex Nihilo

As the above dialogue with the philosophical tradition has already suggested, Castoriadis argued that being is creation. He described creation as an emergence of newness that, whether deliberate or unconscious, is itself not sufficiently determined by preceding historical conditions. He thus described creation as ex nihilo, or as stemming from nothing. Even so, he also insisted that creation is neither in nihilo nor cum nihilo (Castoriadis Reader 321, 404). In other words, while creation must be understood to emerge out of nothing, this creation always emerges within a set of historical or natural conditions. However, these conditions are not sufficient to account for the being of the new creation. Thus, even if there were (per impossible) a complete and exhaustive account of the conditions contextualizing any occasion of creation, neither the existence nor the specificity of the new creation could be fully understood as derived from those conditions. For example, we miss the radical, historical newness of the Greek social creation of “democracy” if we attempt to explain it simply in terms of what already existed in Athens at the time. The creation of democracy broke through the conditioning constraints of the existing social state of affairs. In this sense, Greek democracy was radically new.

Castoriadis repeatedly contrasted ex nihilo creation with production or deduction of consequences. First, production entails that a set of elements or materials is given, which givens are then molded or modified into a new product. Even notions of self-differentiation are really just notions of productivity in this sense, for they envision the new creation (call it X-prime) as emerging from the original X merely as a self-modification of that original X. Thus, the new “product” is treated not as an original itself but rather as a modified “version” of an original. This is not what Castoriadis means by a new creation. Second, in the case of deduction, he argued that a deductive theory of newness would mean only that there is some new conclusion that follows sufficiently from a set of factors as a result of there being a determinate rule or law of the deduction process itself (laws of inference, and so forth). Yet such deduction does not create or reveal something new qua new; rather, it involves an inference from premises to something different that is supposed to already exist because its existence follows from the premises. Thus, he argued, both production and deduction are beholden to theories of “difference” that really only explain the new as a derivative, a modified sameness, or an already-existing thing. Castoriadis contrasted these concepts sharply with creation ex nihilo.

Importantly, Castoriadis’s notion of creation is not equivalent to the epistemic notion of unpredictability, as he clarified in 1983’s “Time and Creation” (World in Fragments 374-401). A continuous emergence of something out of something else can still be fully unpredictable. Unpredictability might, for example, mean simply that not all of the relevant producers, factors, or laws of inference are known or knowable: An unpredictable event or phenomenon could still be determined by unknown factors. Unpredictability could be a function of the limitations of knowledge. Thus unpredictability is not equivalent to creation. While Castoriadis agreed that knowers are not, as far as we know, omniscient, he argued that with each creation there emerges something ontologically new, something that is not merely seemingly new “for us” due to some subjective lack of knowledge. Separating radical creation from the merely epistemic notion of unpredictability, Castoriadis defends the notion that creation brings about something genuinely new.

Further, Castoriadis argued that creation does not prevent deterministic accounts from, so to speak, sticking. Creation cannot be simply opposed to determinism; rather creation only excludes the idea that there could be a total inclusion of the various strata of beings (and creations) within “a single ultimate and elementary level” of determination (World in Fragments 393). Thus, Castoriadis did not deny that creations lend themselves to being understood in terms of continuous difference (production, deduction) or determination. Rather, a stratum of explicable difference always emerges as a result of the relationship of a creation to those conditions in and with (but not from) which it occurs. For example, while Greek democracy was a radically new social creation in history, this creation also at once re-instituted many of the conditions with and in which it emerged. Thus, resultant continuities and (mere) differences are evident between Greek democracy and the world existing prior to its emergence. This stratum of continuity and (mere) difference is somewhat explicable in terms of what is producible or deducible from already existing conditions or elements; but democracy is also something wholly original, something lacking complete continuity with what precedes.

Finally, Castoriadis’s terminology of the ex nihilo should not be confused with the theological sense of creation ex nihilo. Theological creation, he argued, is usually treated as “production” by God according to ideas or pre-existing potentialities, such as the nature or mind of God (Fenêtre sur le Chaos 160-164). A God who looks to ideas that always exist, whether those ideas are God’s own (Augustine) or eternal models not identical to god (Plato), is not thought of as genuinely creative in Castoriadis’s sense. Further, theology usually says the world’s creation is a completed affair. It might play itself out in interesting ways; but this “playing out” does not include the possibility of any radical newness. Thus, traditional solutions to the theodicy problem—whether they involve a God who continually creates the world according to general laws (Malebranche) or a God who creates pre-packaged monads (Leibniz)—always posit that God has a plan established in advance when he creates the world “once and for all.” At its most extreme point, therefore, theological creation is in fact coincident with the most radical necessitarianism (Spinoza). They both deny the radically new. Thus, Castoriadis joked that “spiritualists are the worst materialists” (Fenêtre sur le Chaos 161).

b. Related Theoretical Concepts

i. The Monad and the Social-Historical

In addition to the influence of philosophers, Castoriadis’s account of the imagination was most deeply influenced by his reading of Freud and his engagement with psychoanalysis. This interest became more marked during the years following the end of Socialisme ou Barbarie. At that time he became involved with the L’Ecole Freudienne de Paris (EFP) of Jacques Lacan and was also married for a time to psychoanalyst Piera Aulagnier.

In his interpretation of Freud, Castoriadis focused on the concept of Vorstellungen (representations), especially in the writings from 1915 (World in Fragments 253). He believed Freud’s search for the origins of representations led him closer to the idea of the primary imagination (Section 3.a.1) than did his explorations of the more famous concept of Phantasie (imagination). Castoriadis argued that Freud’s investigations led (implicitly but not explicitly) to the conclusion that for the human psyche there is no strictly mechanical apparatus converting bodily drives into psychical representations. In Castoriadis’s view Vorstellungen are created originally and cannot be accounted for strictly in terms of physical drives or states. Rather, there is an irreducible source of representations, which Castoriadis came to call the monad or the “monadic pole of the psyche.”

Castoriadis’s invocation of the term monad stems, first of all, from the Greek term for unity or aloneness. The term was most famously re-employed by Leibniz to describe the simple, invisible, and sole kind of metaphysical constituent of reality. Leibniz argued that nothing enters or leaves a monad, and yet monads have seemingly interactive experiences due to their pre-established coordination, created by God (i.e. the best possible world). For Leibniz, each monad reflects the state of the other monads and harmonizes with them while remaining independent. Invoking Leibniz’s metaphysics, Castoriadis retained the term but gave it a different sense and value. The monad, for Castoriadis, is not the sole kind of metaphysical constituent but neither is it unreal; rather, the monad is that aspect of the psyche that is incapable of accepting that it itself is not the sole kind of metaphysical constituent. As such, no monad actually remains entirely immanent to itself. All monads are inevitably fractured when the psyche encounters a radical otherness. Following the fragmentation the remnants of the monad desire to recover themselves into a now-impossible state of total aloneness. This “monadical” desire for aloneness has two effects. On the one hand, the monad’s desire for total self-enclosure leads the psyche to disregard the non-psychical sources of human function. The psyche begins to hate and despise the body, sometimes detrimentally. On the other hand, the monad’s desire for unity is not simply a negative thing since it leads the psyche to find unique ways to individuate itself. This individuation often occurs through the psyche’s adoption of social norms and identities. Adoption of norms or identities is not necessarily a bad thing, especially insofar as it can bring a certain measure of stability to the psyche. Castoriadis’s main point was rather that while the monadic pole of the psyche always tends toward radical aloneness, the broader psyche—of which the monad is only an aspect—is in fact capable of socialization, of adopting shared identities, and of having productive relations to others. The monadic pole, however, always fights against subsumption into social or physical norms or identities.

Ultimately Castoriadis felt a need to account for the monadic aspect of the psyche due to his experiences as an analyst interacting with patients. The monad, he suggests, is a necessary hypothesis we must posit if we are to describe the observable history of the patient subsequent to his or her fragmentation (Figures of the Thinkable 168). What follows fragmentation is a phase of life in which the psyche creates itself in relation to a specific social-historical situation and the collective conditions it faces. These collective conditions, or institutions, essentially “fabricate” the individual from out of the psyche as the psyche adopts them into its own identity.

For this reason Castoriadis’s psychoanalytic work leads directly into his political philosophy. For in the same way that psychical creativity as such is broader than, and precedes, the social-historical individuation of the psyche, so too is there a ground of any social formation. This ground, irreducible to individual psychic creativity, Castoriadis calls the anonymous collective. This trans-individual creativity yields as its effects the imaginary formations falling into our typical, narrower categories of “culture” or “society.” A psyche always forms itself through these instituted social offerings; but the social instituting power itself is what accounts in the first place for this instituted state of affairs. The instituted can always be rewritten by the instituting power, and thus a truly autonomous society explicitly acknowledges this instituting power and seeks lucidly to share in it (Section 4).

In this sense, Castoriadis insisted that various strata of creativity—for example, the psyche and the anonymous collective—are irreducible to each other and yet they are importantly interactive. He thus understood that psychoanalysis has a broader social role than is typically believed. In particular it can help the psyche break consciously and lucidly with the monadical desire for total self-enclosure. Castoriadis felt this task could help bring about a world where the singular psyche and the collectivity begin to acknowledge the duty to share in the deliberative activities of distinctively autonomous self-creation (Section 4).

ii. The Living Being and Its Proper World

In addition to his reflection on social and individual human creativity, Castoriadis’s view of “being as creation” led him to develop theories about non-human living beings. In “The State of the Subject Today” (World in Fragments 137-171) he considered in turn the living being, the psyche, the social individual, and finally human society, arguing that each is a distinct but interactive “stratum” of being. While a living being (for example, a human) is conditioned by its interaction with and dependency on other living beings such as cells, nevertheless no stratum of living beings (such as humanity) is reducible to any other stratum. Human life cannot be conceived accurately as merely an “expression” of cell life, for example. Each stratum involves a unique, original kind of living being, or “being for itself,” which leans on but is by no means determined by the other strata with which it interacts.

Beginning at the cellular level then, Castoriadis described the living being as creative of its own proper world as it leans on other beings and worlds which lend themselves. Castoriadis suggested, for example, that an individual dog is a participant in the species dog, in the sense that this dog creates for itself a world in common with other dogs. Nevertheless, while the “proper worlds” of the cells of this dog (or of other beings in its environment) are a condition of this dog and of this dog’s creation of a proper world shared with other dogs, these cells are not something out of which this dog sufficiently emerges or with which this dog’s life is always entirely consistent. Dog cells do not determine the proper world of a dog although they are conditions leaned upon by this dog as it creates its own proper world. While dog-life thus depends on cell-life, the stratum of life proper to dogs is a creation of dogs as they live with their conditioning cells. And, of course, cell life is also creative of a proper world for itself, i.e. a world only partially analogical with the life of the dog. As a result, each stratum of life is unique yet interactive.

On this level, Castoriadis conversed with Chilean biologist and proponent of the theory of autopoiesis Francisco Varela (for example, see “Life and Creation” in Post-Script on Insignificance). For Varela, and also for Humberto Maturana, auto-creation means that each living being creates for itself a world of closure. The living being is essentially dependent upon the living beings which condition it. Higher beings are expressions of the potentialities inherent in the lower constituents. Castoriadis followed Varela with respect to the self-creation of the living being and its proper world, arguing that nothing enters into the proper world of a living being without being transformed by it. However, for Castoriadis, auto-creation did not have to entail a kind of organizational closure. Some living beings are both radically creative of new, irreducible strata of life and merely lean on others for their creations; they are not simply expressions of those other strata. The creativity of a dog, for example, is thus irreducible to being the expression of the constituents of itself (e.g. cells) or the expression of its environment. Even the most basic stratum of natural life (which Castoriadis called the “first natural stratum”) is merely a condition for the emergence of other living beings; it is not something that decides, determines, or produces what those other strata are.

Thus, Castoriadis did not treat the creativity of the living being as simply a larger or smaller scale version of other living beings. The human creation of a proper world, for example, creatively breaks out of a closure relative to its supporting conditions (internal or environmental) and breaks continuity even with itself at times. Humans create a new stratum of being irreducible to the others. We are always intra- and inter-active with other strata; but the human psyche creates in ways that are not contained potentially in anterior states of other living beings or in its inherited conditions. Humans create a new, common, distinct stratum of life. Thus, Castoriadis argued from a biological standpoint that it is quite possible to affirm truly that “everything is interactive.” Yet he insisted that we cannot for that reason “simply say that everything interacts with everything […]” (Post-Script on Insignificance 67). All of what is proper to the human world interacts with some other strata, but only some of what is proper to the human world shares something in common with all other strata.

iii. Magmas and Ensembles

Castoriadis’s project has many aspects that allow it to be interpreted as a “theory of being” in the traditional sense. He developed two important theoretical concepts that underpin much of his ontological work beginning in the 1970s: magmas and ensembles. The former term was Castoriadis’s preferred name for indeterminate, or mixed, being. The latter, the French term for “sets,” is his term for determinate being (where being refers to either the singular or plural).

Castoriadis faced his greatest difficulties in describing magmas since he argued magmas exist and yet they are not comprehensible by traditional ontology because traditional ontology thinks that true being is strictly determinate. Traditional ontology says that what is indeterminate (Greek apeiron) is a more or less deficient being or a kind of non-being. That is, indeterminate being is at best conceived as existing only insofar as it is related to determinate being (Greek peras). Castoriadis’s task was to envision indeterminate being without thinking of it as merely existing relative to, or as a negation of, determinate being. As such, Castoriadis made a very cautious effort to “define” magmas (although he did not consider his task to be possible in this definitional form) in a way that did not define them as deficient modes of determinate being. In the 1983 text, “The Logic of Magmas and the Question of Autonomy” (Castoriadis Reader 290-318), he suggested several propositions:

M1: If M is a magma, one can mark, in M, an indefinite number of ensembles.

M2: If M is a magma, one can mark, in M, magmas other than M.

M3: If M is a magma, M cannot be partitioned into magmas.

M4: If M is a magma, every decomposition of M into ensembles leaves a magma as residue.

M5: What is not a magma is an ensemble or is nothing.

Here the central problem in thinking about magmas is the way that they appear as a great nexus wherein any magma is inseparable from any other magma. Magmas are thus something like mixtures of beings that involve no totally separate or discrete elements. Even so, other magmas, different from any particular magma that is being researched, can be “indicated” as existing within the magma being researched. For this reason, magmas are also not simply one sole entity. Yet they have no parts and always resist being confined to sets. In short, magmas are inherently indeterminate; while they are determinable in some ways, they are never wholly determinate.

As for his account of ensembles, or determinate being, Castoriadis argued that all traditional ontology—including Platonic forms, Aristotelian substance, Kantian categories, the Hegelian absolute, for example—assumes that being is essentially determinate. Such an ontology is, in Castoriadis’s terms, an ensemblist-identitarian, or ensidic, ontology. These ontologies always rely on certain operators of thinking, including traditional logical and mathematical principles such as the principle of identity, non-contradiction, the excluded third, and so forth. They assume that being consists of entirely discrete or separate elements neatly conforming to these principles. Ensidic thought therefore cannot grasp the notion that there would be anything genuinely other than determinate being.

As an example of ensidic thought, Castoriadis referred to set theory and its development. Cantor’s naïve set theory described a set as “any collection into a whole M of definite and separate objects m of our intuition or our thought.” He thus expressed explicitly what all later (non-naive or axiomatic) versions of set theory would maintain implicitly: the assumption that being is wholly determinate or consists of wholly determinate elements. When Cantor’s original set theory was shown to lead to paradoxes (such as Russell’s paradox), later axiomatic set theory did not call into question Cantor’s core pre-assumption that all being is determinate. Instead, it attempted to salvage Cantor’s determinacy assumption by wagering on being’s “conformability” to the determinacy assumption, all while searching for better ways to make that assumption consistent. Axiomatic set theory thus unquestioningly accepted Cantor’s original presupposition, even as it attempted to salvage set theory through axiomatics. Thus, set theory is a paradigmatic case of ensidic thought. Yet it is not unique in its assumption that being must be determinate. Everyday language, for example, already implicitly posits the separation and distinctness of beings. Set-theoretical ontology just re-confirms this bias of everyday language when it presumes that all being is determinate.

The problem with the assumption that all being must be determinate, or ensidic, Castoriadis argued, is not that there is in truth no stratum of determinate being whatsoever. Rather, there is such a stratum of wholly determinate being. The problem is that while this stratum is a condition for the emergence of other beings, it is merely a condition and not the sole constitutive principle of the other strata of being. The assumption that all being must be determinate leads ensidic logic to present some stratum of being (the first natural stratum of sheer determinacy) as if it were solely constitutive of each and every stratum of being (or each and every being). As such, a wholly ensidic ontology wrongly assumes that this de facto condition of determinacy is itself universally constitutive in principle of all possible beings. It falsely assumes that other strata simply conform to the ensidic strata (or stratum) of being. In reality, ensidic thought itself posits this stratum of being as primary, without the attendant awareness that this hypothesis is a hypothesis. Thus, traditional ontology, like everyday language, gravely mistakes the ensidic stratum itself for what being must be.

4. The Project of Autonomy

For Castoriadis, the psyche of each human is inevitably fragmented and cannot remain in a strictly monadic state. Further, as the ground of social-historical constellations of meaning, the creativity of the anonymous collective—i.e. the social instituting power—is irreducible to individual psychic creativity (Section 3.b.i). Thus, the question of genuine politics arises necessarily for humans because humans must create themselves as they exist in relation to others and in relation to society’s institutions (which often mediate relations with others). Therefore, the question of true political action is intimately linked to the question of which institutions we shall institute, internalize, and lean on in our creations. Hence, we must engage in lucid deliberation about what is good for humans and about which institutions help us achieve the good. This lucid deliberation separates genuine politics from demagoguery or cynical politics.

Importantly, genuine deliberation does not merely concern the means to achieving a goal we assume we already know (as Aristotle had supposed in Ethics that our goal of “happiness” is a given and we only need to deliberate about the means to happiness). Rather, we must deliberate about the ends themselves as well as the means. As such, political existence can never arrive at a total, final conclusion. Since no set model of action is given to us (for example, politics cannot be modeled on what is natural or ecological, in accordance with evolution, and so forth), genuine politics cannot assume that any given condition or state of life determines which laws it should lay down for itself and which practices it should support or sanction. Rather, for Castoriadis, genuine politics is a way of life in which humans give the laws to themselves as they constantly re-engage in deliberation about what is good. In short, genuine politics coincides with the question, and the ability of individuals and society to pose the question, What is a good society? Societies and individuals who can genuinely pose this question are capable of autonomy, transcending the closure of the traditions and social conditioning in which they emerge. This capacity for autonomy depends not only on the individuals and society who actually give limits and laws to themselves, but also on those institutions on which individuals and society lean when creating those laws.

a. Heteronomy and Autonomy

In 1989’s “Done and To Be Done,” (Castoriadis Reader 361-417) Castoriadis restated some of the political arguments he had developed since his tenure with Socialisme ou Barbarie. He argued that the problem of traditions covering over the reality of creation (Section 3) is not merely a theoretical error; it also immediately coincides with closure in political and moral reality. All societies are self-creative and yet most, he argued, are utterly incapable of calling into question their own established norms. In such societies, the instituted situation immediately coincides without remainder with what is good and valid in the minds of the people. Such a society, which does not or cannot question its own norms or considers its norms to be given by God, gods, nature, history, ancestors, and so forth, is heteronomous in opposition to autonomous societies.

Castoriadis argued that heteronomy results when nature, essence, or existence are understood to produce the law for the creative living being, for individuals, or for society. On the one hand, Castoriadis’s definition of heteronomy was not limited to, nor did it target, religious beliefs in any special sense. Castoriadis’s examples were at times examples of religious beliefs and at other times examples of closed, but not necessarily religious, societies. In this way, the distinction cuts across any supposed divide between sacred and secular, such that even the most seemingly enlightened and anti-religious materialism could be a dominant instituted imaginary in a largely heteronomous society. In such a society, humans are continuously regenerated in a systematic state of closure. The necessary condition for the project of autonomy is, thus, the breaking of such instituted radical closure, i.e. the rupture of heteronomy.

On the other hand, what is essential for Castoriadis’s positive account of autonomy is that there is no law of nature that is pre-set for the human. That is, there is no substance or rule determining what a human qua human must be or can be. However, this is not to say that the human is nothing at all: The creativity of the human means that humans “cannot not posit norms” (Castoriadis Reader 375). As such, humans can always pose and repose the question of norms and of what they are to be; we can always in principle break away from a heteronomous condition. The radical creativity of the psyche and collectivity is never obliterated by a society or a set of social institutions, even if autonomy is de facto absent. Nevertheless, it is possible for heteronomous societies and individuals to largely cover over this creativity of the human, to institute norms that cannot, in a de facto sense, be called into question.

As a result, Castoriadis did not identify creation (or self-creation) with the moral and political project of autonomy. Rather, even heteronomous societies create themselves and are self-constituting. Autonomy exists only when we create “the institutions which, by being internalized by individuals, must facilitate their accession to their individual autonomy and their effective participation in all forms of explicit power existing in society” (Castoriadis Reader 405). Autonomy thus means not only that tradition can be questioned—i.e. that the question of the good can be posed—but also that we continue to make it de facto possible for ourselves to continue to ask, What is good? The latter requires that we establish institutional supports for autonomy.

For Castoriadis there is therefore an exigency to embrace autonomy in a sense not limited to the liberal ideal of non-coercive, negative freedom wherein coercion as such is depicted as evil (albeit, a necessary evil). Castoriadis argued that the object of genuine politics is to build a people who are capable of positive self-limitation. This self-limitation is not limited to weak suggestiveness; rather, autonomy “can be more than and different from mere exhortation if it is embodied in the creation of free and responsible individuals” (Castoriadis Reader 405). Castoriadis argued, against the liberal ideal, that the elimination of coercion cannot be a sufficient political goal, even if it is often a good thing. Rather, autonomous societies go beyond the negative-liberty project of un-limiting people. Autonomous communities create ways of explicitly, lucidly, and deliberately limiting themselves by establishing institutions through which individuals form their own laws for themselves and will therefore be formed as critical, self-critical, and autonomous. Only such institutions can make autonomy “effective” in a de facto way.

Finally, in defining what he meant by “effective” autonomy, Castoriadis distinguished his view of autonomy from Kant’s. In the Kantian perspective, he argued, the possibility of autonomy involves the possibility of acting freely in accordance with the universal law, itself established once and for all, apart from the influence of any other heteronomous incentives. Castoriadis argued that Kantianism treats autonomy itself as a goal or as something that we want simply for itself. Echoing Hegel, Castoriadis argued that Kantian autonomy ends up as a purely formal issue or a desire for autonomy for itself alone. Castoriadis, like Kant, did not deny the importance of the pursuit of autonomy for itself, with the full knowledge that the law of one’s action is not given from elsewhere. However, he added that we do not desire autonomy only for itself but also in order to be able to make, to do, and to institute. The formal, Kantian autonomy must also be made factual. “The task of philosophy,” he argued, “is not only to raise the question quid juris; that is just the beginning. Its task is to elucidate how right becomes fact and fact right—which is the condition for its existence, and is itself one of the first manifestations thereof” (Castoriadis Reader 404). As such, effective autonomy means that the will for autonomy itself as an “end” must also be a will for the de facto “means” to autonomy, namely the will to establish the institutions on which autonomy leans.

b. Democracy in Ancient Greece

In 1983’s “The Greek Polis and the Creation of Democracy” (Philosophy, Politics, Autonomy 81-123) Castoriadis argued that institutions of autonomy have appeared twice in history: in Athens in the fifth century B.C.E. and in Western Europe during the Enlightenment. Neither example serves as a model for emulation today in institutions. If we recall that the existence of autonomous institutions is never a sufficient condition for autonomy, we realize that there can be no question of treating historical cases as models to emulate. Rather, what makes these cases important, for Castoriadis, is that they are examples where, within societies that have instituted a strict closure, the closure is nevertheless ruptured, opened, and the people reflectively and deliberatively institute a radically new nomos, or law, for themselves.

Societies, argued Castoriadis, tend to institute strict closure: “In nearly all of the cultures that we know of, it is not merely that what is valid for each one is its institutions and its own tradition, but, in addition, for each, the others are not valid” (Post-Script on Insignificance 93). However, Castoriadis argued that Greece—in grasping that other societies do not mirror a nature found everywhere, but are radically creative of their own, unique institutions—also thereby grasped themselves as self-creative of their own institutions. The Greeks broke with their own established social closure and instituted “lucid self-legislation.” The Greek discovery of social self-creation (i.e. the social instituting power) led to the partial realization (institution) of autonomy precisely because they both effectively imagined their potential universality with others as an end (formal autonomy) and yet also established some particular institutions as supports for autonomy’s effective realization. Even so, the Greek creation remained partial and its institutions were limited and narrow (for example, they excluded women). Castoriadis’s point was that the potential universality of their creation (radical criticism and self-criticism), which they understood to be their own creation, coincided with the democratic institutions established as supports for rendering autonomy effective. In the end, the Greeks inaugurated a tradition of radical criticism that is, for Castoriadis, always something with which autonomy—and philosophy—begins.

c. Public, Private, and Agora

Castoriadis did not shy from suggesting some specific institutional characteristics that autonomous societies embrace. While he cautioned that there can be no a priori or final decision about what autonomous society should be, he proposed in “Done and To Be Done” (Castoriadis Reader 361-417) a classical, three-pronged institutional arrangement of society’s strata. These strata are:

ekklésia—the public/public

oikos—the private/private

agora—the public/private

In defining these terms, Castoriadis insisted that the first necessary condition of an autonomous society is the rendering open of the public/public sphere, or ekklésia. The task is to make self-institution by individuals and society explicit through the public consideration of the works and projects that commit the collectivity and the individual. The ekklésia is not a sphere of bureaucratic management of individuals by social architects; quite the opposite, it entails the establishment of institutions for public knowledge production and lawmaking, thus making possible an intellectual space for individuals to know and question laws in an informed way. Such considerations that affect individuals cannot, however, be left to the private/private or the public/private spheres; they must be undertaken by the collectivity together in public. There seems to be no requirement that the ekklésia occupy what we commonly call a physical place; rather, the site for knowing, deliberating about, and questioning the law is any space that “belongs to all (ta koina).” What is important is that the ekklésia involves the collectivity in a public deliberation about the goals and means of society and individuals.

Second, Castoriadis argued that an autonomous society will render the private/private sphere, or oikos, inviolable and independent of the other spheres. Individuals, families, and homes create themselves with institutions. That is, private life, as it creates itself, leans on an instituted fabric of society, a fabric the very continuation of which must be the subject of deliberation in the ekklésia. This fabric includes the institutions for education, basic criminal law, and other society-wide conditions. Bureaucratic communism or socialism, insofar as they destroy individual personality and private life, are to be abolished through the ekklésia’s efforts to support the independence and distinctness of the private/private sphere.

Third, Castoriadis defended the independence of the public/private, mixed sphere, i.e. the agora. His defense of the term the Greeks used for their marketplace has nothing to do with any defense of so-called free enterprise (i.e. merely negative liberty to exploit workers). Rather, the agora is where individuals (and not a particular set of individuals, as was the case in Athens, where citizen males alone participated) can group themselves in relation to others for purposes that are not explicitly questions pertaining to the public/public sphere. The independence of the agora as a mixed sphere would eliminate the possibility of forced collectivization of goods or the need for the abolition of money forms, which are still useful in the agoric sphere. The agoric sphere provides a kind of buffer between the tyrannies of the wholly public or wholly private set of interests, thus supporting the ongoing institution of autonomy as a whole.

For Castoriadis, each of the three institutional strata should be treated as a proper sphere of its own. They should not be collapsed into one sphere. “Autonomous society,” he wrote, “can only be composed of autonomous individuals” (World in Fragments 416). The preservation of each stratum is vital. Yet, on the one hand, the statist and bureaucratic societies of the twentieth century, despite their intentions of establishing a genuine public sphere, constantly collapsed the potential universality of the public/public sphere into a massive, all-inclusive private/private stratum, i.e. into a manipulative, bureaucratic society. On the other hand, the Western liberal democracies were more properly oligarchic, totalitarian-capitalist societies that happen to exist in a somewhat more fragmented and less total form than their statist counterparts. They too tend to collapse the public/public into private, bureaucratic, capitalist corporations. They thereby generate people who do not know the law and therefore cannot question it or effectively institute new laws. Thus, autonomy—while always in principle possible for us—is nevertheless factually foreclosed across most of the world, even to this day.

5. References and Further Reading

a. Book-Length Collections of Castoriadis’s Work in English

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. A Society Adrift: Interviews and Debates, 1974–1997. Trans. Helen Arnold. New York: Fordham University Press, 2010.

- This text contains full articles of a largely political tenor as well as occasional writings and interviews.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. Crossroads in the Labyrinth. Trans. Martin H. Ryle and Kate Soper. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- This text contains several important essays; however, it includes only a few of the essays to be found in the six-volume French title.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. Figures of the Thinkable. Trans. Helen Arnold. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007.

- This text contains a variety of important articles, including important theoretical pieces, such as “Remarks on Space and Number.”

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. On Plato’s Statesman. Trans. David Ames Curtis. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002.

- Castoriadis provides a close and critical reading of the Plato dialogue while engaging with other Greek thinkers and sources. (Also, these lectures are only part of a larger collection of Castoriadis’s course materials, which are slowly being published in French).

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. Philosophy, Politics, Autonomy. Essays in Political Philosophy. Trans. and Ed. David Ames Curtis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- This text is the best single collection of Castoriadis’s political works.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. Political and Social Writings, Volume 1: 1946–1955. From the Critique of Bureaucracy to the Positive Content of Socialism. Trans. and Ed. David Ames Curtis. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

- These volumes collect many of Castoriadis’s political writings, from occasional pieces to the full-scale, multi-part articles from Socialisme ou Barbarie.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. Political and Social Writings, Volume 2: 1955–1960. From the Workers’ Struggle against Bureaucracy to Revolution in the Age of Modern Capitalism. Trans. and Ed. David Ames Curtis. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

- This text contains “Modern Capitalism and Revolution,” and, along with Vol. 3, tracks the break with Marxism.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. Political and Social Writings, Volume 3: 1961–1979. Recommencing the Revolution: From Socialism to the Autonomous Society. Trans. and Ed. David Ames Curtis. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

- This text, along with Vol. 2, tracks Castoriadis during his break with Marxism.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. Post-Script on Insignificance: Dialogues with Cornelius Castoriadis. Trans. Gabriel Rockhill and John V. Garner. New York: Continuum Press, 2011.

- This text contains dialogues with Octavio Paz, Alain Connes, Francisco Varela, and others. A helpful introduction by Rockhill clarifies many concepts and offers criticism of some of Castoriadis’s historiographical assumptions.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. The Castoriadis Reader. Trans. and Ed. David Ames Curtis. New York: Blackwell Publishing, 1997.

- This text is the most comprehensive single collection of Castoriadis’s work.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. The Imaginary Institution of Society. Trans. Kathleen Blamey. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987.

- This text is Castoriadis’s most famous single work and the second half contains Castoriadis’s most sustained single piece of writing.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. World in Fragments. Writings on Politics, Society, Psychoanalysis, and the Imagination. Trans. David Ames Curtis. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

- This text contains a helpful introduction by Curtis focusing on Castoriadis’s engagement with the history of science. It is the most comprehensive collection other than the Castoriadis Reader.

b. Secondary Readings (French and English)

- Adams, S. Castoriadis’s Ontology: Being and Creation. New York: Fordham University Press, 2011.

- In addition to this full-scale study of Castoriadis that situates his work in the context of continental philosophy and twentieth-century social thought, Adams has published several strong articles, focusing especially on Castoriadis’s notion of physis and trans-human creativity.

- Bachofen, B., Elbaz, S., and Poirier, N. Ed. Cornelius Castoriadis: Réinventer l’autonomie. Paris: Éditions du Sandre, 2008.

- This French-language text contains essays by several thinkers, including Edgar Morin, that focus on autonomy and ontology.

- Bernstein, J. Recovering the Ethical Life: Jürgen Habermas and the Future of Critical Theory. London: Psychology Press, 1995.

- Bernstein’s text includes a thoughtful chapter on Habermas’ criticism of Castoriadis.

- Busino, G. Ed. Autonomie et Autotransformation de la Société. La Philosophie Militante de Cornelius Castoriadis. Geneva: Droz, 1989.

- This text is a multilingual collection of essays on Castoriadis.

- Callinicos, A. Trotskyism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990.

- In one chapter Callinicos argues that Castoriadis initiates volunteerism in order to save revolutionary possibilities.

- Elliott, A. Critical Visions: New Directions in Social Theory. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2003.

- Elliott’s work, this text and several others, contains frequent references to Castoriadis.

- Habermas, J. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures. Trans. Thomas McCarthy. Oxford and Cambridge: Polity and Blackwell Press, 1987.

- Habermas makes a normative critique, challenging Castoriadis’s ability to value one imaginary over another. He also famously charges that Castoriadis posits a kind of self-producing social demiurge.

- Honneth, A. “Rescuing the Revolution with an Ontology: On Cornelius Castoriadis’s Theory of Society” Thesis Eleven. Trans. Gary Robinson, Vol. 14. 1986. 62-78.

- Honneth more or less follows Habermas’ criticism.

- Joas, H. “Institutionalization as a Creative Process: The Sociological Importance of Cornelius Castoriadis’ss Political Philosophy,” Pragmatism and Social Theory. Trans. Raymond Meyer. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993. 154-171.

- This article provides a helpful review of Castoriadis’s work on language and articulation.

- Kalyvas, A. “The Politics of Autonomy and the Challenge of Deliberation: Castoriadis contra Habermas.” Thesis Eleven. Vol. 64. Feb. 2001. 1-19.

- Kalyvas defends Castoriadis against Habermas-style criticism.

- Kavoulakos, K. “The Relationship of Realism and Utopianism in the Theories of Democracy of Jurgen Habermas and Cornelius Castoriadis.” Society and Nature. Vol. 6. Aug. 1994. 69-97.

- Kavoulakos has published several essays on Castoriadis’s work.

- Klooger, J., Castoriadis: Psyche, Society, Autonomy, Boston: Brill, 2009.

- Klooger provides a critical, informed, and thoughtful review of all aspects of Castoriadis’s work, focusing on the later material, including the implications of Castoriadis’s work for physics and ontology. Especially helpful is his critical discussion of Castoriadis’s too-relativistic comments on physics, which, he argues, make it seem as if Newtonian mechanics corresponds to a stratum of being that it describes better than relativity does.

- Klymis, S. and Van Eynde, L. L’Imaginaire selon Castoriadis. Thèmes et Enjeux. Brussels: Facultés Universitaire Sain-Louis et Bruxelles, 2006.

- This text is a collection of essays in French on a variety of themes in Castoriadis’s work.

- Leibowitz, M. Beyond Capital. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

- This text contains a full-scale defense of Marx, as opposed to Castoriadis-style objections, by suggesting that Capital is one side of a larger dialectical picture: Marx intended to write a companion work from the standpoint of workers, rather than merely from the perspective of capitalists.

- Poirier, N. L’ontologie Politique de Castoriadis: Création et Institution. Paris: Éditions Payot et Rivage, 2011.

- Poirier interrogates Castoriadis’s theory of democratic institutions with a view to their openness to creativity. The work also contains helpful discussions of Castoriadis in relation to Marx’s view of praxis and Lefort’s critique of totalitarianism.

- Rorty, R. “Unger, Castoriadis, and the Romance of a National Future” Critique and Construction: A Symposium on Roberto Unger’s Politics. Eds. Robin W. Lovin and Michael J. Perry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. 29-45.

- Rorty positively assesses the break with Marxism and briefly defends Castoriadis contra Habermas.

- Stavrakakis, Y. The Lacanian Left: Psychoanalysis, Theory, Politics. Albany: SUNY Press, 2007.

- Stavrakakis reads Castoriadis from a Lacanian perspective and attempts to mediate their differences.

- Thesis Eleven. “Cornelius Castoriadis” Special Issue. Vol. 49. May 1997.

- This issue of the Australian journal contains several helpful assessments of Castoriadis’s work by a variety of thinkers.

Author Information

John V. Garner

Email: jgarner@westga.edu

The University of West Georgia

U. S. A.