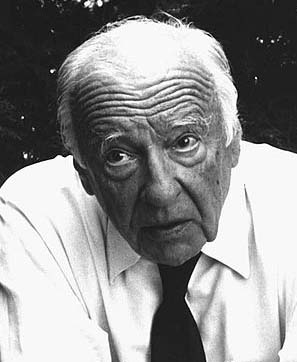

Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900—2002)

Hans-Georg Gadamer was a leading Continental philosopher of the twentieth century. His importance lies in his development of hermeneutic philosophy. Hermeneutics, “the art of interpretation,” originated in biblical and legal fields and was later extended to all texts. Martin Heidegger, Gadamer’s teacher, completed the universalizing of the scope of hermeneutics by extending it beyond texts to all forms of human understanding. Hence philosophical hermeneutics inquires into the meaning and significance of understanding for human existence in general.

Hans-Georg Gadamer was a leading Continental philosopher of the twentieth century. His importance lies in his development of hermeneutic philosophy. Hermeneutics, “the art of interpretation,” originated in biblical and legal fields and was later extended to all texts. Martin Heidegger, Gadamer’s teacher, completed the universalizing of the scope of hermeneutics by extending it beyond texts to all forms of human understanding. Hence philosophical hermeneutics inquires into the meaning and significance of understanding for human existence in general.

Gadamer was influenced by Heidegger’s interest in the “question of Being,” which aimed to draw our attention to the ubiquitous and ineffable nature of Being that underlies human existence. “Being” refers to something like a “ground” (although not in the modern sense of “foundation”) or, better, background, that precedes, conditions, and makes possible the particular forms of human knowing as found in science and the social sciences. Gadamer developed Heidegger’s commitment to the ubiquitous and fundamental nature of Being in three related ways.

First, Gadamer wanted to elucidate the historical and linguistic situatedness of human knowing and to emphasize the necessity and productivity of tradition and language for human thought. For example, when Gadamer wrote that “Being that could be understood is language,” he meant that Being underlies, exceeds, and makes possible language.

Second, Gadamer sought to contend against the hubris of twentieth century positivism by demonstrating that truth is not reducible to a set of criteria, as is suggested by promoters of there being a scientific method. Just as Heidegger set out to uncover the way in which Being makes beings possible, so Gadamer aimed to demonstrate that truths derivable from method require a deeper, more extensive Truth. In order to extend truth’s domain beyond that of method (and note that Gadamer was never against method or science—only their totalizing tendencies), Gadamer explicates truth as an event. Truth is not, fundamentally, what can be affirmed relative to a set of criteria but an event or experience in which we find ourselves engaged and changed. These first two points form the emphasis of his magnum opus, Truth and Method (Wahrheit und Methode).

A third way of understanding Gadamer’s defense of the ubiquity of Being can be seen in the practical trajectory of Gadamer’s hermeneutics that arises from his interest in Plato and Aristotle. From Plato, Gadamer discerns the centrality of dialogue as the means by which we come to understanding. Dialogue is rooted in and committed to furthering our common bond with one another to the extent that it affirms the finite nature of our human knowing and invites us to remain open to one another. It is our openness to dialogue with others that Gadamer sees as the basis for a deeper solidarity. With Aristotle, Gadamer affirms the commitment that all philosophy starts from praxis (human practice) and that hermeneutics is essentially practical philosophy. We must not allow knowing to remain only on the conceptual (that is, distanced and theoretical) level; we must remember that knowing emerges from our practical quest for meaning and significance. Gadamer’s hermeneutics elucidates how Being makes human existence meaningful, where Being refers to commonality we all share.

Gadamer’s many essays and talks on ethics, art, poetry, science, medicine, and friendship, as well as references to his work by thinkers in these fields, attest to the ubiquity and practical relevance of hermeneutic thought today.

Table of Contents

- Biography

- Hermeneutic Inceptions

- “Foundations” of Philosophical Hermeneutics: Truth and Method

- Critical Encounters

- Practical Philosophy: Hermeneutics Beyond Gadamer

- References and Further Reading

1. Biography

a. Early Years: Platonic Urges

Hans-Georg Gadamer was born on February 11, 1900 in Marburg, Germany. Two years later his family moved to Breslau where his father took up the position of professor of pharmacological chemistry. The presence of his domineering, strict Prussian father devoted to natural science, and the absence of his deeply pietistic mother (who died in 1904 from diabetes) perhaps contributed to Gadamer’s interest in poetry and the arts. In his words, poetry and the arts were the closest things an “unredeemed agnostic” had to contend with the limits of human knowing (Gadamer: A Biography, 20-23).

In 1918 Gadamer began his studies at Breslau and then moved to the University of Marburg, where his father received a teaching position and later became rector. At Marburg, Gadamer first studied with Richard Hönigswald, who introduced him to neo-Kantianism, and then with Nicolai Hartmann, whose brand of phenomenology presented challenges to the neo-Kantianism of Hönigswald. Hartmann’s critique of neo-Kantianism proved a crucial impetus for Gadamer’s own thinking, including his subsequent turn away from neo-Kantianism. Yet Gadamer eventually came to question Hartmann’s rigid epistemology due to the fact that it remained committed both to Aristotelian realism and to an impoverished form of phenomenology, which failed to take seriously the importance of the knower’s perspective. Gadamer accused Hartmann’s phenomenology of not being radical enough since it ignored the more fundamental conditions of human knowing.

In 1922 Gadamer wrote his (unpublished) thesis with Paul Natorp on “The Nature of Pleasure according to Plato’s dialogues” (despite Natorp’s initial suggestion to write on Fichte). Natorp, himself a prominent Plato scholar and neo-Kantian at the time, took over in the wake of the declining influence of the neo-Kantians at Marburg. In Gadamer’s thesis we find the seeds of his later writings on Plato and Aristotle, gleaned from Natorp, that emphasized the unity of the one and the many, the forms, and the realm of sensuality. Gadamer was not only influenced by the mysticism of Natorp but also by the esotericism of the poet Stefan George, of whose circle he was a member. While a definitive causality is impossible to prove, one can detect connections between the recurrent challenge to scientism that pervades Gadamer’s later, explicitly hermeneutic philosophy and the various “mysticisms” of Plato, Natorp, George, and Heidegger. What can be defended, however, is that what united the “mysticisms” of these thinkers, and thus inspired Gadamer, was their gesturing towards the realm beyond being that exposes the limitations of human understanding. While some used their “mysticism” to avoid the prosaic cares of daily life—cares that only blocked our access to this loftier, more radical and thus worthier realm—Gadamer rejected such an escapism and instead extolled “mysticism” for its propensity to insist on the finitude of human existence. True to his own unique interpretation of Plato that sought to refuse simplistic dualisms, Gadamer advocated acknowledging the beyond while at the same time insisting on our practical existence. In other words, human thinking always requires an acknowledgment of what cannot be fully captured in language, yet at the same time language, as that part of Being that can be understood, functions to create our human world and funds meaning. These themes of the productivity of the liminal or “horizonal”(for example, as developed by his notion “fusion of horizons”), and language’s in-between status, were born out of his early “Platonism” and served to undergird his later hermeneutic philosophy.

b. Middle Years: Under the Influence of Heidegger

Gadamer first encountered the written work of Heidegger in 1921 after reading one of Heidegger’s papers on Aristotle. Heidegger’s Aristotelian phenomenology, which refused the reductionism of Husserl’s phenomenology, provided Gadamer with the tools and impetus to deal the final blow to his earlier tendencies toward neo-Kantianism. During the summer of 1923 he pursued studies with Heidegger in Freiburg, where he also attended classes of Edmund Husserl, who although Heidegger’s teacher, stood in his shadow. When Heidegger was offered a position as chair at Marburg in October 1923, Gadamer followed him, a move that exacerbated the tension between Heidegger and Hartmann since many of Hartmann’s students ended up leaving him to study with Heidegger. Fellow students at Marburg during that period included Hannah Arendt, Hans Jonas, Jakob Klein, Karl Löwith, and Leo Strauss. Gadamer’s work with Heidegger was initially delayed due to Gadamer’s contraction of polio in 1922, which later served to exclude him from military service. It was during Gadamer’s convalescence that Hartmann worked to arrange a marriage for Gadamer to Frida Katz in 1923, with whom he had a daughter, Jutta, in 1926.

It should be noted that Gadamer’s relationship with Heidegger was an ambivalent one. Early on, Gadamer had thought he would write his Habilitation (doctoral dissertation) with Hartmann, but then he set his sights on Heidegger. However, Heidegger was initially unimpressed by Gadamer’s philosophical potential and encouraged him to pursue philology instead. Gadamer followed his advice and spent a number of years studying Plato with Paul Friedländer, from whom he learned about Plato’s dialogic and dialectic philosophy, an emphasis that would prove central to Gadamer’s later hermeneutics. In 1928, upon hearing of Gadamer’s plan to write his Habilitation with Friedländer, Heidegger reversed his earlier view of Gadamer’s incompetence as a philosopher and wrote a letter inviting Gadamer to work with him. In 1929 Gadamer took up a teaching position at Marburg and completed his Habilitation with Heidegger, published in 1931 as Plato’s Dialectical Ethics.

In 1933, while teaching courses on ethics and aesthetics at Marburg, Gadamer signed a declaration in support of Hitler and his National Socialist regime. Did this mean that like his teacher, Heidegger, he was an unabashed supporter of National Socialism? If so, as some suggest (Orozco), why would Gadamer have expressed shock months earlier when Heidegger had announced his own support for National Socialism? And why did Gadamer intentionally cultivate and maintain friendships with Jews during those years, while distancing himself from Heidegger until after the war? Gadamer’s biographer, Jean Grondin, offers details of Gadamer’s actions and inactions during this vexed period, and concludes that while Gadamer may have lacked the political savvy and courage for resistance, he was, unlike Heidegger, no Nazi. Reflecting back in later years Gadamer describes his shortsightedness: “it was a widespread conviction in intellectual circles that Hitler in coming to power would deconstruct the nonsense he had used to drum up the movement, and we counted the anti-Semitism as part of this nonsense. We were to learn differently” (Gadamer: A Biography, 75).

c. Later Years: Truth and Method and Beyond.

In 1939 Gadamer became a professor at Leipzig, where his first course was “Art and History,” which, as Grondin maintains, paved the way for his magnum opus, Truth and Method, published in 1960. In the same year, his first festschrift, which includes an essay by Heidegger, was also published. At Leipzig, Gadamer served as dean of the Philology and History Department and the Philosophy Faculty, as well as director of the Psychology Institute and in 1946 became rector. Unhappy due to political criticism launched at him, he sought a position in the west and initially taught at Frankfurt (1948) before accepting Karl Jasper’s offer to chair the philosophy department at Heidelberg (1949), where he taught until his official “retirement” in 1968. In 1950 he married again, this time to his former student and member of the resistance, Käte Lekebusch, with whom he had a daughter, Andrea, in 1956.

It was not until after his retirement that he gained status as an international thinker and a philosopher in his own right. This influence was due to several reasons. First, important debates with Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida served to distinguish philosophical hermeneutics as a serious contender against both the critique of ideology and deconstruction. Second, he spent nearly twenty years teaching and lecturing in the United States each fall semester. Finally, Truth and Method was published in English in 1975. He continued to teach and lecture internationally and in Germany into his one-hundredth year. Gadamer died on March 13, 2002 in Heidelberg, while recovering from heart surgery. Today he is recognized as the preeminent voice for philosophical hermeneutics. Four claims focus the significance and originality of his hermeneutics: 1) hermeneutic philosophy is fundamentally practical philosophy, 2) truth is not reducible to scientific method, 3) all knowing is historically situated, and 4) all understanding reflects the ubiquity of language.

2. Hermeneutic Inceptions

a. Plato

Gadamer acknowledged that Plato, far more than Hegel or any other German thinker, motivated and inspired all his hermeneutics. Gadamer, though, remains no “traditional” Platonist, for, his early work on the Ancient Greeks is devoted to an attentive and nuanced re-reading of the significance of Plato for us today. What distinguishes Gadamer’s work on Plato is his desire to understand the questions and problems that motivated Plato. This approach stands opposed to attempts, common in Ancient Greek scholarship of the early twentieth century (for example, Leo Strauss and his followers), to uncover the “hidden doctrine” of Plato. In attempting to answer why Plato wrote his dialogues and what he was arguing against, Gadamer incites us not just to put questions to Plato—which can lead to an excessively distanced criticism of Plato—but to allow Plato to question us. The radical return to Plato made Gadamer all the more receptive to and excited by the thinking of Heidegger who also sought to understand Aristotle anew and in a more radical way.

As a result of his unique approach, Gadamer’s interpretation of Plato avoids the standard dualism (entrenched in part, Gadamer tells us, by Aristotle’s literalist readings of his teacher) that pits the Good-Beyond-Being against the good-for-us. Gadamer emphasizes the productive, rather than problematic, nature of the chorismos (the separation) between the sensual world of appearances and the transcendent realm of the forms. In other words, pace Aristotle, this separation was necessary and productive and not something to be overcome. Gadamer follows Plato in insisting on the ontological nature of the Good. Far from an empty concept, as Aristotle charged, the Good serves as an assumption that makes possible all understanding. The Good symbolizes the way in which thinking always “points beyond itself” (Philosophical Apprenticeships, 186). The plethora and variety of appearances must be made sense of in light of the assumption that something lies beyond our present understanding—namely, the Idea of the Good. Plato appealed to the Good in order to criticize the ethical relativism of the Eleatics. Gadamer draws our attention to how Plato’s appeal to the Good allowed him to transform Eleatic dialectic in two important ways: 1) to direct it towards getting clear about the “subject matter” (die Sache) as opposed to having as its goal the defeat of one’s opponent with logical prowess, and 2) to ground it in Socratic dialogue. Gadamer himself sought to recover the emphasis on the early Platonic dialectic, while refusing its later Hegelian instantiation, in order to return philosophy to Plato’s original intention as a dialectic defined primarily as the “art of carrying on a conversation” (Philosophical Apprenticeships, 186). The key to Gadamer’s later hermeneutics is grasping the significance of how Gadamer understands the connection between Platonic dialectic and Socratic dialogue.

b. Aristotle

Gadamer also returns anew to Aristotle. By stressing the import of Aristotle’s practical philosophy as that which emphasizes the background, that is, the conditions, for knowing, Gadamer challenged one of the leading Aristotelians of his day, Werner Jaeger. All knowing always starts from practical human concerns and must not lose its way in abstraction (a charge Gadamer later made against the Critique of Ideology). Gadamer’s interest in practical philosophy and its basis in human experience motivated hermeneutics’ ethical sensibilities, for instance, as witnessed in Gadamer’s esteem of phronesis as a key hermeneutic principle. What Gadamer wants to draw out from phronesis is the way in which knowledge is for the sake of acting, in other words, for the sake of living. An excessively theoretical or scientific knowledge forgets that knowledge stems out of and must return to praxis. But what sort of knowledge is sufficient for action conditioned by the variability of human life? The knowledge appropriate for the task is what Aristotle names as “phronesis.” Such a knowledge requires application but not in the way that modern science understands application: namely, the secondary and discrete step that follows from a prior theoretical knowledge. Neither is it adequately expressed by “judgment” (as in its later Kantian instanciation that subsumes a particular under a universal). Phronesis rejects the theory-practice dualism of both of these models of knowledge and instead entails the ability to transform a prior communal knowledge, that is, sensus communis, into a know-how relevant for a new situation. It is this requirement for human judgment emerging forth from a specific human community that Gadamer describes as reflective of hermeneutic understanding. The ethical overtone of phronesis as a hermeneutic concept suggests the way in which this knowledge is directed toward right action based on a “universal” (that is, communal rather than transcendent) knowledge. As Gadamer explains in Truth and Method, while “hermeneutical consciousness is involved neither with technical nor moral knowledge” (315) there is an overlap with the latter to the extent to which it entails right action based primarily on the ability to make one’s own that which comes to one out of a community. Such knowledge emerges out from and returns to praxis. Accordingly, one of Gadamer’s key contributions to philosophy, and one that took him beyond his teacher, Heidegger, was to insist that hermeneutics is practical philosophy. Gadamer clarifies that practical philosophy is rooted in human existence, which is never solipsistic but always communal. Rejecting the absolutism of modernity, Gadamer’s philosophy emphasized experience, but not the isolated existence of much 19th and 20th century existentialism. Rather, for Gadamer, existence means existing with others, which requires dialogue born of humility and an openness for inquiry: “hermeneutic philosophy understands itself not as an absolute position but as a way of experience. It insists that there is no higher principle than holding oneself open in a conversation” (Philosophical Hermeneutics, 189).

3. “Foundations” of Philosophical Hermeneutics: Truth and Method

a. Truth Beyond Science

Heidegger referred to his own early work as “hermeneutical philosophy,” and after his “turn” quipped that he wanted to leave the business of hermeneutics to Gadamer. Gadamer himself was never sure whether this was a compliment or a criticism! Nonetheless, Gadamer did develop hermeneutics beyond Heidegger’s use of that term, which can be seen foremost in Gadamer’s unique concept of truth, as developed most fully in Truth and Method.

Originally titled by Gadamer as Foundations of a Philosophical Hermeneutics, Truth and Method is just that. Following Heidegger’s initiative to increase the scope of hermeneutics beyond that of texts, Gadamer endorses the insight that humans are fundamentally beings who are given to understanding. Our task, if we are to truly know ourselves, is to figure out what such understanding entails, taking into account both its possibilities and limitations. Gadamer, however, goes further than Heidegger and asks if this is the case, what specifically does this mean for the humanities (Geisteswissenschaften)? Gadamer’s answer has both negative and positive components. Negatively, Truth and Method is critical of not only the methodologism and scientism underlying the hermeneutics of Dilthey and the phenomenology of Husserl, but also the twentieth century proclivity for positivism and/or naturalism. Yet in his move to put science “in its place,” so to speak, one finds a positive attempt to reinvigorate our appreciation of art, showing not only how it speaks truth but also how it serves as the paragon of truth. He argues not only that meaningful knowledge sought by the humanities is irreducible to that of the natural sciences, but that there is deeper, richer truth that exceeds scientific method. However, this commitment does not mean, as Jürgen Habermas and Paul Ricoeur maintained, that Gadamer opposes truth to method. For such a conclusion misses the crucial point that for Gadamer all forms of methodological truth are dependent on this deeper sense of hermeneutic truth. What sort of truth is it that underlies yet is not limited to natural scientific truth?

Over and against traditional conceptions of truth, Gadamer argues that truth is fundamentally an event, a happening, in which one encounters something that is larger than and beyond oneself. Truth is not the result of the application of a set of criteria requiring the subject’s distanced judgment of adequacy or inadequacy. Truth exceeds the criteria-based judgment of the individual (although we could say it makes possible such a judgment). Gadamer explains in the last lines of Truth and Method that “In understanding we are drawn into an event of truth and arrive, as it were, too late, if we want to know what we are supposed to believe” (490). Truth is not, fundamentally, the result of an objective epistemic relation to the world (as put forth by correspondence or coherence theories of truth). An objective model of truth assumes that we can set ourselves at a distant from and thus make a judgment about truth using a set of criteria that is fully discernible, separable, and manipulable by us. Gadamer’s point is that there is a more fundamental happening of truth that is irreducible to such methodological applications, which perhaps we could call verisimilitudinous in regards to the deeper, hermeneutic, sense. Gadamer aims not to negate scientific method but to elucidate 1) what makes it possible and 2) the limitations of its scope. Gadamer is interested in dispelling the hubris of science (that is, scientism born of positivism) and not denigrating the practice of science per se. Furthermore, Gadamer took pains to clarify in his foreword to the second edition of Truth and Method that he is not offering a new method for hermeneutics or the social sciences. His work is not prescriptive. But neither is it descriptive of human behavior. He tells us: “My real concern was and is philosophic: not what we do or what we ought to do, but what happens to us over and above our wanting and doing” (xxviii). This statement also reveals the influence that Heidegger’s retrieval of the question of Being had on Gadamer’s thought in general, and his account of truth in particular. Gadamer’s critique of a scientific or modern theory of truth was, like much of Heidegger’s thought, a critique of subjectivism. Specifically, Gadamer maintained that the knower is never able to fully conceptualize and judge his or her own belief structure. Yet Gadamer’s account of truth went further than Heidegger’s and entailed a second claim, namely, that truth is fundamentally practical. Let us take a closer look at each of these two claims.

Regarding his anti-subjectivism, Gadamer describes the event of truth as an experience in which one is drawn away from oneself into something beyond oneself. To experience truth requires losing oneself in something greater and more extensive than oneself. The paradigmatic example of such an anti-subjective experience is play, to which Gadamer devotes quite a bit of space in Truth and Method. In order to appreciate the anti-subjective emphasis of play, it is helpful to understand its “medial” (Truth and Method, 103, 105) nature: players do not direct or control the play but are caught up in it. Play has “primacy over the consciousness of the player” (104), follows its own course, and plays itself, so to speak. Play is not played by a subject but rather absorbs the player into itself. Gadamer’s primary concern is to elucidate what it means to be caught up in the game in a way that diminishes the subjectivity of the player. In fact, the subject of the game is not the player but the game itself. However, this emphasis does not mean that the player relinquishes all power or consciousness and dons a zombie-like state—in which case there would be no mediality. Rather, Gadamer’s point is that play is effortless, without strain, and spontaneous (105), always enticing one into more play. The fact that in play one experiences oneself as in-between oneself and the play, that is, one neither exerts full control nor is passively swept along, reflects its mediality.

The constant back-and-forth movement of play eludes the grasp and guidance of an agent’s will, and yet, at the same time, is seemingly full of initiative. Play succeeds when the player engages in it with ease and where the player is never awkward or removed. But neither is the play excessively competitive. Gadamer’s insistence on the “contested” nature of such movement emphasizes the fact that one always plays with something or someone else. By “contest” Gadamer means to suggest only that play is never the act of a lone individual—not that it is necessarily agonistic. The negative component of competition that some (Lugones) read into Gadamer is difficult to defend given Gadamer’s insistence that the goal of play is not to end the game by winning but to keep on playing. While there is an initial assertive and intentional choice of entering into a game, once the game has gotten underway, being caught up in the game replaces any prior intentionality. To play, as Gadamer suggests, is to choose to give up our choice. In play, one substitutes one’s “free, individual choice,” so to speak, for the experience of a new sort of freedom which entails losing oneself in reciprocal play with someone or something else. The alleged “freedom” to remain isolated, in control, and able to choose is replaced by the freedom found in relinquishing oneself to the play of the game.

In addition to its medial nature, Gadamer highlights a second feature of play, namely “presentation,” which is what ultimately allows Gadamer to explain how play becomes transformed into art. Gadamer insists that human play is always marked by self-presentation: in play we present ourselves as something/someone else. While there is self-presentation in nature, according to Gadamer, human play-as-self-presentation is different:

The self-presentation of human play depends on the player’s conduct being tied to the make-believe goals of the game, but the “meaning” of these does not in fact depend on their being achieved. Rather, in spending oneself on the task of the game, one is in fact playing oneself out. The self-presentation of the game involves the player’s achieving, as it were, his own self-presentation by playing—that is, presenting—something. Only because play is always presentation is human play able to make representation itself the task of the game. (Truth and Method, 108)

What Gadamer is getting at here is that the purpose of play is not a presentation of a final, completed product for a third-party observer. Rather, he clarifies how in play our only goal is to figure out how to represent ourselves so that the game continues, thus recalling the contestial nature of play that requires two and aspires to keep playing. In other words, in true play the goal is not to achieve the prize but to present oneself as something in such a way that furthers the play.

Gadamer describes how play becomes “art” when the presentation is aimed at the absence of the “fourth wall”—that is, the viewer. Whereas in games the presentation is self-contained, in art, play-as-presentation does aim at something beyond itself. The playful self-presentation characterizing mediality gets transformed into pure presentation in art, signifying a potential for truth not found in the anti-subjective dimension of play. However, Gadamer warns, “when we speak of play in reference to the experience of art, this means neither the orientation nor even the state of mind of the creator or of those enjoying the work of art, nor the freedom of subjectivity engaged in play, but the mode of being of the work of art itself” (Truth and Method, 101). To grasp exactly what Gadamer means by “the mode of being of the work of art itself” we can now attend to the second claim Gadamer raises about truth, namely, its practical importance. Art exemplifies how truth is a matter of being spoken to, being claimed, and being changed. The truth emerging from art is an existential, practical one, rather than a purely theoretical one.

For Gadamer, truth is inextricably tied to our ability to recognize “something and oneself” (Truth and Method, 114). Unlike previous theories, however, that tied recognition to the ability to recognize the original presented by art, Gadamer emphasizes the future, rather than the past, as defining recognition. Recognition aimed at the truth of art stems not from its ability to mimic (or correspond to) an original but from its ability to bring to presence that which is truer than the original. To encounter the truth in art is not to look back to an original; art serves not as the mirror to the world-that-is-really-there, but as a means to opening one’s eyes to new ways of seeing and future possibilities. It is new visions not past ones that can count as true, and for this reason Gadamer insists that what is presented in art is actually more true than the alleged original it purports to imitate. But what does this mean and how does it reflect truth’s practical bent? Recognition thus requires more than objective seeing where one brackets one’s subjectivity and remains at an existential distance from the art. Recognition means being played by, drawn into, the work of art in such a way that one’s own being is altered. As Gadamer puts it, our encounter with art that produces truth occurs when we hear the art speaking as if directly to us: “it is not only the ‘This art thou!’ disclosed in a joyous and frightening shock; it also says to us; ‘Thou must alter thy life!’” (Philosophical Hermeneutics, 104). The neutral gaze of aesthetic consciousness affords no truth, for nothing is at stake, nothing is disturbed, and everything is left as it was before. For Gadamer, the truth of art refers to its practical ability to speak to, that is, change, the viewer. Art’s “mode,” then, is “presentation” (Truth and Method, 115) to the extent to which it presents an “essential” truth, where “essence” refers not to a stable, a priori, but to the relation established by our encounter with the art. To lose oneself in the play of art that then leads to a finding and a recognition of oneself—one that activates an envisioning of oneself in the future and not the past—is to experience truth. Gadamer writes, “In being played the play speaks to the spectator through its presentation; and it does so in such a way that, despite the distance between [the play and the spectator], the spectator still belongs to play” (116). The belongingness is not one that suggests a “deep, hidden truth,” as Dreyfus and Rabinow maintain, but rather one in which we experience ourselves made present with the art—which is possible only as we look ahead, envisioning ourselves anew.

To maintain the evential character of truth is to expose the dynamic nature of understanding, specifically in terms of a “double movement” (Barthold). Gadamer’s account of truth requires not only that one be drawn away from oneself and caught up in something larger than oneself, one must also “return to oneself.” Here, the “return to self” means the ability to grasp the meaning for oneself in a way that changes one. As we have seen, Gadamer does not just offer a critique of modern subjectivism, he also argues for the practical moment in which one feels compelled to change one’s life. The anti-subjective implication of Gadamer’s account of truth, to the extent it is a move away from oneself, is suggestive of the Platonic motion of ascendance. And the subsequent impetus for practical application, the return to oneself, reflects the descendance also reminiscent of Plato. If we do not engage in such a dynamic experience, one both in which one is caught up and from which one emerges changed, then one has not experienced truth. This hermeneutic account of truth refrains from explicating the method or the criteria required to arrive at a correct judgment. Instead it attempts to elucidate the more primordial sense of truth that underlies, but does not oppose, traditional accounts of truth like the correspondence and coherence theories.

b. Prejudice, Tradition, Authority, Horizon

In part II of Truth and Method Gadamer develops four key concepts central to his hermeneutics: prejudice, tradition, authority, and horizon. Prejudice (Vorurteil) literally means a fore-judgment, indicating all the assumptions required to make a claim of knowledge. Behind every claim and belief lie many other tacit beliefs; it is the work of understanding to expose and subsequently affirm or negate them. Unlike our everyday use of the word, which always implies that which is damning and unfounded, Gadamer’s use of “prejudice” is neutral: we do not know in advance which prejudices are worth preserving and which should be rejected. Furthermore, prejudice-free knowledge is neither desirable nor possible. Neither the hermeneutic circle nor prejudices are necessarily vicious. Against the enlightenment’s “prejudice against prejudice” (272) Gadamer argues that prejudices are the very source of our knowledge. To dream with Descartes of razing to the ground all beliefs that are not clear and distinct is a move of deception that would entail ridding oneself of the very language that allows one to formulate doubt in the first place. To further understand the vital role of prejudices, we must examine the role Gadamer assigns to tradition.

“Tradition,” like “prejudice,” is a term Gadamer develops beyond its everyday meaning. To affirm, as Gadamer does, that one can never escape from one’s tradition, does not mean he is insisting we endorse all traditions writ large. Gadamer is not espousing a conservative approach to tradition that blindly affirms the whole of a tradition and leaves one without recourse to critique it. Critics like Habermas and Ricoeur have faulted Gadamer for failing to insist on a critical response to tradition. These criticisms miss the mark for two reasons. First, accepting the fact that we can never entirely reflect oneself out of tradition does not mean that one cannot change and question one’s tradition. His point is that in as much as tradition serves as the condition of one’s knowledge, the background that instigates all inquiry, one can never start from a tradition-free place. A tradition is what gives one a question or interest to begin with. Second, all successful efforts to enliven a tradition require changing it so as to make it relevant for the current context. To embrace a tradition is to make it one’s own by altering it. A passive acknowledgment of a tradition does not allow one to live within it. One must apply the tradition as one’s own. In other words, the importance of the terms, “prejudice” and “tradition,” for Gadamer’s hermeneutics lies in the way they indicate the active nature of understanding that produces something new. Tradition hands down certain interests, prejudices, questions, and problems, that incite knowledge. Tradition is less a conserving force than a provocative one. Even a revolution, Gadamer notes, is a response to the tradition that nonetheless makes use of that very same tradition. Here we can also perceive the Hegelian influences on Gadamer to the extent that even a rejection of some elements of the tradition relies on the preservation of other elements, which are then understood (that is, taken up) in new ways. Gadamer desires not to affirm a blind and passive imitation of tradition, but to show how making tradition our own means a critical and creative application of it.

Similarly, true authority always requires an active acknowledgment by others. Without such an acknowledgment, one finds not true authority but passive submission resulting in tyranny. For, acknowledgment requires an active implementation of and reflection on the meaning of that authority for oneself—one based in knowledge not ignorance. Hence, understanding always has a built-in possibility for critique as we strive to make something our own and do not simply passively mimic it. Memorizing a text, for example, is no indication that one understands it; one has understood only when one can put the text into one’s own words, enlivening the text and allowing it to speak in new ways. That Gadamer’s point is not a conservative one is seen by the fact that change resulting in a new creation is the necessary result of all understanding.

Gadamer’s attention to the historical nature of understanding is captured by what he terms, “historically effected/effective consciousness” (Wirkungsgeschichtliches Bewusstein). But against historicism’s objectifying tendencies, Gadamer contends that historical situatedness does not result in restrictive limitations. For, limits are precisely what allow one to be open to what is new. It is in this context that one of Gadamer’s most misunderstood terms, namely, the “fusion of horizons,” is discussed. “Horizon” suggests the limits that make perspective possible and is marked by two main features. First, the concept of horizon suggests the situated and perspectival nature of knowing. Just as the visual (that is, literal) horizon provides the boundaries that allow one to see, so the epistemic horizon provides boundaries that make knowledge possible. Just as the literal horizon delimits one’s visual field, the epistemic horizon frames one’s situation in terms of what lies behind (that is, tradition, history), around (that is, present culture and society), and before (that is, expectations directed at the future) one. The concept of horizon thus connotes the way in which a located, perspectival knowing is yet a fecund one: without the limitation of a horizon there would be no seeing. The back- and fore-grounds requisite for knowledge are not hindrances to be overcome. For, the “view from nowhere” sees not; it is blinded by its own solipsism. A horizon, as Gadamer tells us, bespeaks the productively mediated relation between what is distant and near; it enables us to discern both what is close up and what is far away without excluding either of these positions (Truth and Method, 302). We could say that the concept of horizon meaningfully integrates the interpreter’s immediate environs and the more distant world-at-large.

Second, Gadamer stresses the open and dynamic nature of horizons. This point has been neglected in some of the secondary literature devoted to Gadamer’s conception of horizon and for this reason it is important to note that when Gadamer speaks of the horizon it is in a context in which he is trying to explain how we can have an intellectually vital relation with tradition or, as he puts it later, between “text and present” (306). Against historicism, Gadamer argues that the ability of a contemporary interpreter to understand a text of the past does not presuppose two entirely distinct, reified horizons. It is the work of understanding to expose the unity to what at first glance is taken to be two distinct horizons, that is, past and present. Hence the “fusion” of horizons that signifies understanding. Rather than delineating a fixed and impenetrable space, Gadamer wants to highlight the capaciousness and expansiveness of a horizon: “horizon is. . . something into which we move and that moves with us. Horizons change for a person who is moving” (304). To defend horizons as distinct and fixed affirms the closed (304), incommensurable nature of horizons, where understanding, and thus truth, remains thwarted (303).

Since Gadamer denies the original diremption (separation) of discrete horizons, he rejects the assumption that understanding requires us to transpose ourselves into another, alien horizon. Horizons are not self-contained locations that can be entered into or departed from at will; they are not “objective” locations distinct from us as “subjects.” It is not the case, then, that understanding requires an act of will by which we transpose ourselves into the horizon of the other. The Hegelian themes are clear when Gadamer tells us that the transposition that occurs in the attempt to understand

always involves rising to a higher universality that overcomes not only our own particularity but also that of the other. The concept of “horizon” suggests itself because it expresses the superior breadth of vision that the person who is trying to understand must have. To acquire a horizon means that one learns to look beyond what is close at hand—not in order to look away from it but to see it better, within a larger whole and in truer proportion. (305)

The Hegelian aufhebung (sublation) underlying horizontal fusions means that whenever we are tempted to say that there are two completely distinct and incommensurate horizons we should confess the superficiality and incompleteness of such a description. That is to say, our initial efforts at trying to interpret an ancient text might make it seem as if the text does belong to an entirely different world, and Gadamer does not deny that the foreignness of the text sometimes seems to suggest its complete otherness. Misunderstanding can exacerbate the otherness of the other. But, accepting the initial challenge of difference as entailing ontologically real differences precludes change, and thus understanding. Instead, Gadamer invites us to conceive of difference as a means to transformation, which Gadamer terms “fusion of horizons.” The temptation to treat difference as an impossibility reflects a superficial response and affirms a rigid, reified notion of horizon. Noting the difference of temporally or spatially distant worlds, is, as Gadamer puts it, “only one phase in the process of understanding,” and we must take care not to “solidify” the “self-alienation of past consciousness” (306, 307). If we do so, then we will prevent the “real fusing of horizons. . . which means that as the historical horizon is projected, it is simultaneously superseded” (307). Refusing to reify difference means acknowledging that the process of understanding requires the ability to allow one’s own horizon to shift and change in light of the acknowledgment of the other, and vice versa. True understanding not only begins with difference but also requires all horizons to change; neither one’s own horizon nor that of the other is left intact (306-307). Fusion of horizons is not a war in which the dominant horizon swallows up the weaker one. In keeping with Gadamer’s anti-subjectivism, it is crucial to note that the “fusion of horizons” happens beyond our willing; the expanding of our horizon is not something we can fully control or bring about. Rather, it is through our effort to understand that a new horizon emerges.

But if there are not two reified horizons, neither is there a single, bounded horizon that occludes difference. Fusion refers to the active and the on-going nature of understanding—not a static, hegemonic unity. Any unity wrought by understanding is its effect—not its cause. Furthermore, such unity will never be total: understanding refers to a process not a final end. To defend a mono-culture is akin to positing a single, definite horizon and is thus to deny the very difference that initiates understanding in the first place. The productivity of such difference is attested to by Gadamer’s statement in his “Afterword” to Truth and Method: “what I described as a fusion of horizons was the form in which this unity [of the meaning of a work and its effect] actualizes itself, which does not allow the interpreter to speak of an original meaning of the work without acknowledging that, in understanding it, the interpreter’s own meaning enters in as well. . . Working out the historical horizon of a text is always already a fusion of horizons” (576, 577). Acknowledging that one can only access the viewpoint of another from within one’s own horizon is not a totalitarian effort to defend a mono-culture but a humble admission that one never can access directly the other’s perspective. Neither an imposed nor feigned sameness is the starting place; if they were there would be no work for understanding to do. Ascriptions of a mono-horizon belong to historicist positions that fail to note the complex nature of horizons that always, at least potentially, grant provisions for us moving beyond them. Gadamer’s account of horizon emphatically maintains that only where one is open to new horizons emerging—and hence difference—can one claim to understand. It falls to the work of the historical consciousness, which Gadamer seeks to undermine, to defend such a mono-cultural and reified picture of history and tradition. Hence, Gadamer’s theory is not forced to assume either a mono-cultural view of tradition or to posit mono-culture as the telos of understanding. Putting it in a slightly different way: difference is the occasion for—not an impediment to—understanding.

c. Dialectic, Dialogue, Language

Part II of Truth and Method closes with an analysis of Plato’s dialectic and the significance of dialogue for Gadamer’s hermeneutics. Gadamer’s understanding of these terms as well as how they are related bears comment. As we have seen, Gadamer distinguishes between early Platonic, later Platonic, and Hegelian dialectic and relies most heavily on the early Platonic dialectic due to its reliance on Socratic dialogue. The later Platonic and Hegelian dialectic he faults for their propositional and sentential reductionism. For Gadamer, dialectic instructs his own hermeneutics in so far as it suggests a productive tension that, contrary to Hegel’s view, is never resolved. The lack of resolution suggests the fecundity of the “chorismos” (the separation between the sensual and transcendent realms) marking human existence and affirms our human status as “in-between.” If Gadamer’s hermeneutics can be called “dialectic” it is in the sense that Gadamer affirms that understanding is inseparable from dialogue and is marked by a constant and productive “chorismatic” tension between these two realms (Barthold).

For Gadamer, as for Plato, dialectic is inseparable from (although not reducible to) dialogue. One can point to four main components of dialogue in Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics. First, a dialogue is focused on die Sache, the subject matter. The aim of dialogue is not to win the other over to one’s side—it is not a debate. Nor does it aim at a subjective understanding of the other. Rather, both parties open themselves to coming to an agreement about the matter itself. Secondly, a dialogue requires that each party possesses a “good-will” to understand, that is, an openness to hear something anew in such a way as to forge a connection with another. Thus one could say that dialogic openness aims at solidarity. Third, a good dialogue entails a willingness to offer reasons and justifications for one’s views. One must be open not only to the voice of the other, but to make the effort to explain oneself to another. Finally, a good dialogue requires a commitment that one “knows one doesn’t know.” Dialogue requires a humble playfulness in which we get caught up and lose ourselves in the connection with another. A good dialogue is one that, like engaging play, is one we want to keep going. Thus we could see that the play of dialogue indicates the central motif of Gadamer’s notion of truth: “To reach an understanding in a dialogue is not merely a matter of putting oneself forward and successfully asserting one’s own point of view, but being transformed into a communion in which we do not remain what we were” (379). The intertwined nature of dialectic and dialogue, combined with dialogue’s connection to solidarity, reflects what Gadamer meant when he referred to his philosophical hermeneutics as “dialectical ethics” (“Gadamer on Gadamer”, 15).

Part III of Truth and Method turns to an analysis of language where Gadamer draws on his early fascination with Socratic dialogue in order to defend the importance of the linguistic nature of human existence. Referencing Augustine and Nicholas of Cusa, he goes on to stress the speculative nature of language in order to contend against those who would reduce language to propositions. Gadamer shows us how meaning comes through linguistic expression that relies on a whole (that is, Being) that is greater than its part (what is expressed in language, for example, propositions). This “totality” makes language possible and functions “not [as] an object but the world horizon that embraces us.” But it is crucial to emphasize that the sense of the speculative and the totality Gadamer insists upon here refuses the Hegelian finality: understanding does not aim at having the final word.

But neither is there the worry that we are somehow trapped inside language. Instead, Gadamer stresses the open and on-going nature of understanding that manifests itself in two ways. First, as we have seen, one is to remain open toward the other in order to keep the conversation going. Second, Gadamer stresses the openness on the part of language, which is never a restrictive, non-porous boundary, but a productive limit that makes possible the continual creation of new words and worlds. The first of these, that is, our openness to the on-going conversation we have with others is made possible by the second, that is, our shared pre-linguistic world of being. Thus when it comes to language, Gadamer refuses to reduce language to propositions—that is, tools that we use objectively. Instead he summons poetry as that which embodies what is essential to all language, namely, its status as “a medium where I and world meet, or, rather, manifest their original belonging together” (Truth and Method, 474). In this section, Gadamer proclaims his famous utterance, “Being that can be understood is language” (474). This claim means neither that everything is language nor that all Being is reducible to language. Language, Gadamer tells us towards the end of this section, is a type of presentation, a coming-into-being, that reveals the unity of beauty (that is, what we desire) and truth (what speaks to and changes us). Language, in other words, makes visible both truth and beauty. In this way, language reflects the hermeneutic experience in terms of being captivated by beauty and changed by truth, a truth that is irreducible to scientific method.

4. Critical Encounters

a. E.D. Hirsch

Two years prior to his 1967 book, Validity and Interpretation, E.D. Hirsch wrote a journal article criticizing Gadamer’s hermeneutics. Against Gadamer, Hirsch argued that meaning can only be found in the author’s intention and thus a good interpretation is one that successfully reconstructs and reproduces this original meaning. He accused Gadamer’s hermeneutics of substituting this sort of reconstruction of authorial intention with the interpreter’s own subjective construction. Essentially, Hirsch rejected Gadamer’s move to replace mimesis with application. Hirsch also attacked Gadamer’s reliance on prejudice, tradition, historicity and his notion of fusion of horizons. None of these notions, according to Hirsch, gives adequate emphasis to the importance of the interpreter suspending and bracketing her own subjective consciousness and taking on that of the author. (Thus Hirsch followed Dilthey’s and Schleiermacher’s emphasis on divining the intention of the author as the method of interpretation.) As a result, Gadamer’s hermeneutics is thought to lose its ability to claim objective status and remains unable to defend itself against charges of relativism. What this criticism overlooks, however, is that Gadamer insists his work is not a prescriptive or normative call to endorse prejudice, tradition or authority. It does not defend the passivity of the interpreter but the active and creative force at play in all interpretation. Neither did Gadamer intend “to offer a general theory of interpretation and a differential account of its methods. . .” Instead, Gadamer maintains that the insights of Truth and Method aim “to discover what is common to all modes of understanding and to show that understanding is never a subjective relation to a given ‘object’ but to the history of its effect; in other words, understanding belongs to the being of that which is understood” (Truth and Method, xxxi). Gadamer nowhere denies the importance of striving to be objective when interpreting a text; what he denies is the sufficiency and primacy of such “objectivity.”

b. Jürgen Habermas

In the nineteen-sixties Gadamer had been a supporter of Jürgen Habermas, urging against Max Horkheimer that Habermas be offered a job at Heidelberg before he had completed his Habilitation. While Habermas and Gadamer were united in their attack on the hubris of positivism, during the seventies an important philosophical disagreement between them took place that served to expand the sphere of Gadamer’s philosophical influence. While there were many fundamental points of agreement between Habermas and Gadamer, such as their starting place in the hermeneutic tradition that attempts a critique of the dominance of natural scientific method as well as their desire to return to the Greek notion of practical philosophy, Habermas argued that Gadamer’s emphasis on tradition, prejudice, and the universal nature of hermeneutics blinded him to ideological operations of power. Habermas interpreted Gadamer as calling for the elimination of method altogether and went on to argue that Gadamer’s hermeneutics thus leaves one without the ability to reflect critically upon the sources of ideology at play in the theoretical and material levels of society. Habermas asserted, “Hermeneutical consciousness is incomplete so long as it has not incorporated into itself reflection on the limit of hermeneutical understanding” (The Hermeneutic Claim to Universality, 302). Essentially, he accused Gadamer of failing to recognize the need to critique tradition, inferring that Gadamer disallows such a critique and endorses a dogmatic stand toward tradition. How do we know that the understanding we arrive at is distortion-free? Gadamer’s appeal to tradition, prejudice, and authority would seem to thwart any such critique. Gadamer, in turn, argued, that to refuse the universal nature of hermeneutics is itself the more dogmatic stance, for in so doing we affirm modernity’s deception that the subject can free itself from the past.

c. Jacques Derrida

While both Gadamer and Derrida were attentive to the role of language in life and philosophy, and both were followers of Heidegger, the content as well as the style of their philosophy differ greatly. For Gadamer, the very possibility of understanding requires a devotion to die Sache, the subject matter. Derrida’s deconstructionist claim is that to assume a subject matter, a singular point unifying the attention of understanding, is to endorse and remain ensnared by a metaphysics of presence. According to Derrida there is no subject matter, no “Truth,” only multiple perspectives and their deferral. In 1981, a “meeting” or “conversation” was arranged between Gadamer and Derrida at the Goethe Institute in Paris. However, what occurred fell far short of anything that could be called a philosophical dialogue. Why? Gadamer’s initial presentation aimed to defend Heidegger against Derrida’s charge that Heidegger fails to achieve the more radical philosophy of Nietzsche who insists that there is not truth, no single correct interpretation or agreement over a singular subject matter. Derrida’s “reply,” however, ignored the main trajectory of Gadamer’s points and instead attacked Gadamer for relying on a Kantian notion of the good will. Since Gadamer had mentioned only once (and in passing) the importance of being open to the other in a dialogue, Derrida seemed to overreach with his charge that Gadamer was therefore defending a Kantian notion of good will. Then, even more puzzlingly, in Derrida’s subsequent presentation, he addressed himself only to Heidegger and Nietzsche and made no mention at all of Gadamer’s hermeneutics. Yet if we characterize Gadamer’s hermeneutics as the elucidation of how understanding can succeed, and if we generalize Derrida’s deconstruction as the exposure of the misunderstandings, ruptures, and deviances that always present themselves when we try to understand, then perhaps, to the extent to which each philosopher embodied his own philosophy, a certain encounter (albeit not a dialogue) between philosophies did in fact occur.

5. Practical Philosophy: Hermeneutics Beyond Gadamer

a. Hermeneutics as Dialogue: Ethical and Political Interventions

Tracing the trajectory of Gadamer’s philosophical career, one might question whether Truth and Method deserves to be called his magnum opus or whether it is not one moment in his more important quest to recover the spirit of Plato. If we are to take him at his word that Truth and Method offered us the foundations of hermeneutics, then we must ask, what is the magnum opus such a foundation undergirds? It would seem as if practical philosophy is the work, the edifice, Gadamer hoped would be sustained by his “foundations.” This fact can be substantiated by his 1996 claim: “By hermeneutics I understand the ability to listen to the other in the belief that he could be right” (quoted in Gadamer: A Biography, 250). In other words, Gadamer realizes more fully the universalizing tendency in the history of hermeneutics: the event of understanding occurs not just in the realm of texts, and certainly not just in philosophy, but in the myriad ways we interact with and seek to connect with others.

The eagerness to conceive of the dialogical impetus of hermeneutics as a possible resource for resolving certain contemporary social and political crises in our world is found in much of the secondary literature on Gadamer. Gadamer’s work proves relevant for contemporary issues to the extent to which it neither appeals to prior, transcendent, eternal truths nor devolves into incommensurability. The desire to forge a third way “beyond objectivism and relativism” (Bernstein) captures the move by some thinkers to find social and political relevance in Gadamer’s hermeneutics (Warnke, Sullivan, Dallmayr). Political theorist and philosopher Fred Dallmayr, for instance, drawing on Gadamer, stresses “integral pluralism” as a way to avoid the isolated pluralism resulting from incommensurability. To what extent is it possible to interact rationally and dialogically in order to listen to the other and to advance human understanding that values the whole (that is, community) over the part (individual)? And feminist philosophers Georgia Warnke and Linda Martín Acloff have relied on Gadamer’s hermeneutics in their writings about justice, contemporary social issues, and gender.

b. Twentieth Century Anglo-American Appropriations

While Gadamer’s thought has been primarily formed by his interaction with German and Greek thinkers, it has been taken up by three of the most influential American philosophers of the later twentieth century, namely, the pragmatist Richard Rorty, and the philosophers of language, Robert Brandom and John McDowell. While coming from a very different philosophical tradition than Gadamer, both Brandom and McDowell have argued for the usefulness of Gadamer’s thought for contemporary discussions in philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. Richard Rorty, in his 1979 work, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, was one of the first Anglo-American philosophers explicitly to attest to the import of Gadamer’s hermeneutics. And while the term “hermeneutics” drops out of use in Rorty’s later work, evidence of Gadamer’s continued influence remains. In fact, one can find increasing connections among pragmatism and Gadamer. For example, contemporary American pragmatist Richard Bernstein finds Gadamer’s conception of the fluidity of horizons more promising than that of static paradigms for forging our way through contemporary multiculturalism and globalization. For, Gadamer’s rich and nuanced conception of dialogue avoids promoting either incommensurability or facile dialogue that denies the workings of power in language.

c. Applied Hermeneutics

That Gadamer’s work has also found application in psychology (Chessick), education (Gallagher), ethics (Foster, Smith, Vilhauer), political theory (Dallmayr, Kögler, Sullivan, Warnke), sports (Hyland), and theology (Ringma, Thiselton) affirms Gadamer’s claim that “a good test of the idea of hermeneutics itself” is its ability to find translation in other fields (The Philosophy of Hans-Georg Gadamer, 17). How to make the questions of our history, of our tradition, speak again to us—not solely within the halls of the academy with its “scholarshipism” (as Gadamer terms it) but to the practical concerns of our age? This is the task Gadamer’s hermeneutic philosophy calls us to. Thus the continued relevance of Gadamer’s thought for contemporary philosophy, particularly of a social and political bent, serves to endorse Gadamer’s own claim about the practical relevance of his hermeneutics: “The hermeneutic task of integrating the monologic of the sciences into the communicative consciousness includes the task of exercising practical, social, and political reasonability. This has become all the more urgent” (Philosophical Apprenticeships, 182).

In closing, we can concur with Robert Dostal who clarifies that although Gadamer himself wrote no ethics or political philosophy per se, there is in his hermeneutics a “basic posture” oriented toward just these concerns, to the extent that he urges us to listen, truly listen, to what the other says in trust that she or he may be right. And that this is a posture that extends beyond the realm of academic philosophy can be seen in Gadamer’s own life. Dostal reflects, “The ethic of this hermeneutic is an ethic of respect and trust that calls for solidarity. Gadamer himself embodies this ethic, not only in his work, but also in his life. All those who have encountered him, whether they find themselves in agreement with him or not, have found him, like the Socrates he so much admired, always ready for conversation” (32). And like Socrates’ death, Gadamer’s death did not put an end to our conversation with him.

6. References and Further Reading

a. Collected Works in German

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Gesammelte Werke. Tübigen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck).

b. Main Books by Gadamer in English

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Hegel’s Dialectic: Five Hermeneutical Studies. Trans. P. Christopher Smith. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Philosophical Hermeneutics. Trans. and ed. David E. Linge. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Dialogue and Dialectic. Trans. P. Christopher Smith. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Philosophical Apprenticeships. Trans. Robert R. Sullivan. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1985.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. The Idea of the Good in Platonic-Aristotelian Philosophy. Trans. and with an introduction and annotation by P. Christopher Smith. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Dialogue and Deconstruction. Ed. Diane P. Michelfelder and Richard E. Palmer. Albany: SUNY Press, 1989.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. “Gadamer on Gadamer.” In Gadamer and Hermeneutics, ed. Hugh Silverman. New York: Routledge Press, 1991a.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Plato’s Dialectical Ethics. Trans. Robert M. Wallace. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991b.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Hans-Georg Gadamer on Education, Poetry, and History. Ed. Dieter Misgeld and Graeme Nicholson. Trans. Lawrence Schmidt and Monica Reuss. Albany: SUNY Press, 1992.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Truth and Method. 2nd ed. Trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall. N.Y.: Crossroad, 1992.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Reason in the Age of Science. Trans. Frederick G. Lawrence. Mass.: MIT Press, 1992.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Heidegger’s Ways. Trans. John W. Stanley. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. The Enigma of Health. Trans. Jason Gaiger and Nicholas Walker. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. The Relevance of the Beautiful. Ed. Robert Bernasconi. Trans. Nicholas Walker. N.Y.: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. The Beginning of Philosophy. Trans. Rod Coltman. N.Y.: Continuum, 1998.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg.. Praise of Theory. Trans. Chris Dawson. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Hermeneutics, Religion, and Ethics. Trans. Joel Weinsheimer. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Gadamer in Conversation. Ed. and trans. Richard E. Palmer. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. The Beginning of Knowledge. Trans. Rod Coltman. N.Y.: Continuum, 2002.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. A Century of Philosophy. Trans. Rod Coltman with Sigrid Koepke. N.Y.: Continuum, 2004.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. The Gadamer Reader: A Bouquet of the Later Writings. Ed. Richard E. Palmer. Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2007.

c. Selected Secondary Literature

- Alcoff, Linda Martín. Visible Identities. New York: Oxford, 2006.

- Barthold, Lauren Swayne. Gadamer’s Dialectical Hermeneutics. Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2010.

- Bernstein, Richard. Beyond Objectivism and Relativism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1983.

- Brandom, Robert. Tales of the Mighty Dead. Massachusetts: Harvard University, 2002.

- Chessick, Richard. “Hermeneutics of Psychotherapists,” American Journal of Psychotherapy 44 (1990), 256-73.

- Dallmayr, Fred. Integral Pluralism: Beyond Culture Wars. Kentucky: University of Kentucky, 2010.

- Dostal, Robert J. ed. The Cambridge Companion to Gadamer. New York: Cambridge, 2002.

- Foster, Matthew. Gadamer and Practical Philosophy. Atlanta: Scholars, 1991.

- Gallagher, Shaun. Hermeneutics and Education. Albany: SUNY, 1994.

- Grondin, Jean. Gadamer: A Biography, trans. Joel Weinsheimer. New Haven: Yale University, 2003.

- Grondin, Jean. Introduction to Philosophical Hermeneutics. New Haven: Yale University, 1994.

- Habermas, Jürgen. “The Hermeneutic Claim to Universality.” The Hermeneutic Tradition. Gayle Ormiston and Alan Schrift, ed. Albany: SUNY, 1990.

- Habermas, Jürgen. “A Review of Gadamer’s Truth and Method.” The Hermeneutic Tradition. Gayle Ormiston and Alan Schrift, ed. Albany: SUNY, 1990.

- Hahn, Lewis Edwin, ed. The Philosophy of Hans-Georg Gadamer. Chicago: Open Court, 1997.

- Hirsch, E.D. “Truth and Method in Interpretation.” Review of Metaphysics 18 (1965), 488-507.

- Hirsch, E.D. Validity in Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University, 1967.

- Hollinger, Robert, ed. Hermeneutics and Praxis. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, 1985.

- Hyland, Drew. Philosophy of Sport. St. Paul, Minn.: Paragon House, 1990.

- Kögler, Hans Herbert. The Power of Dialogue: Critical Hermeneutics after Gadamer and Foucault. Translated by Paul Hendrickson. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 1996.

- Krajewski, Bruce, ed. Gadamer’s Repercussions. Berkeley: University of California, 2004.

- Lugones, Maria. “Playfulness, “World”-Traveling, and Loving Perception,” Hypatia 2 (1987), 3-19.

- McDowell, John. Mind and World. Cambridge, Mass.,: Harvard, 1996.

- Michelfelder, Diane P. and Richard E. Palmer. Dialogue and Deconstruction: The Gadamer-Derrida Encounter. Albany: SUNY, 1989.

- Orozco, Theresa. “The Art of Allusion: Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Philosophical Interventions Under National Socialism,” Radical Philosophy 78 (1996), 17 26.

- Ringma, Charles Richard. Gadamer’s Dialogical Hermeneutics. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 1999.

- Rorty, Richard. Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. New Jersey: Princeton, 1979.

- Rorty, Richard. “Being That Can Be Understood Is Language.” Gadamer’s Repercussions. Ed., Bruce Krajewski. Berkeley: University of California, 2004.

- Smith, P. Christopher. The Ethical Dimension of Gadamer’s Hermeneutical Theory. Research in Phenomenology 18 (1988), 75-91.

- Sullivan, Robert. Political Hermeneutics. Pa.: Pennsylvania State University, 1989.

- Thiselton, Anthony C. The Two Horizons. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, 1980.

- Vilhauer, Monica. Gadamer’s Ethics of Play. Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2010.

- Warnke, Georgia. Gadamer: Hermeneutics, Tradition and Reason. Stanford: Stanford University, 1987.

- Warnke, Georgia.Walzer, Rawls, and Gadamer: Hermeneutics and Political Theory. In Festivals of Interpretation, ed. Kathleen Wright. Albany: SUNY, 1990.

- Warnke, Georgia. Justice and Interpretation. Mass.: MIT, 1993.

- Warnke, Georgia. Legitimate Differences. Berkeley: University of California, 1999.

- Weinsheimer, Joel C. Gadamer’s Hermeneutics. New Haven: Yale University, 1999.

Author Information

Lauren Swayne Barthold

Email: lsbarthold@gmail.com

Endicott College

U. S. A.