Sartre’s Political Philosophy

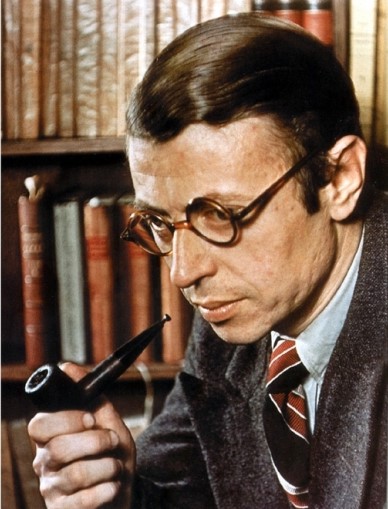

French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), the best known European public intellectual of the twentieth century, developed a highly original political philosophy, influenced in part by the work of Hegel and Marx. Although he wrote little on ethics or politics prior to World War II, political themes dominated his writings from 1945 onwards. Sartre co-founded the journal Les Temps Modernes, which would publish many seminal essays on political theory and world affairs. The most famous example is Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew, a blistering criticism of French complicity in the Holocaust which also put forth the general thesis that oppression is a distortion of interpersonal recognition. In the 1950’s Sartre moved towards Marxism and eventually released Critique of Dialectical Reason, Vol. 1 (1960), a massive, systematic account of history and group struggle. In addition to presenting a new critical theory of society based on a synthesis of psychology and sociology, Critique qualified Sartre’s earlier, more radical view of existential freedom. His last systematic work, The Family Idiot (1971), would express his final and most nuanced views on the relation between individuals and social wholes. Sartre’s pioneering combination of Existentialism and Marxism yielded a political philosophy uniquely sensitive to the tension between individual freedom and the forces of history. As a Marxist he believed that societies were best understood as arenas of struggle between powerful and powerless groups. But as an Existentialist he held individuals personally responsible for vast and apparently authorless social ills. The chief existential virtue—authenticity—would require a person to lucidly examine his or her social situation and accept personal culpability for the choices made in this situation. Unlike competing versions of Marxism, Sartre’s Existentialist-Marxism was based on a striking theory of individual agency and moral responsibility.

French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), the best known European public intellectual of the twentieth century, developed a highly original political philosophy, influenced in part by the work of Hegel and Marx. Although he wrote little on ethics or politics prior to World War II, political themes dominated his writings from 1945 onwards. Sartre co-founded the journal Les Temps Modernes, which would publish many seminal essays on political theory and world affairs. The most famous example is Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew, a blistering criticism of French complicity in the Holocaust which also put forth the general thesis that oppression is a distortion of interpersonal recognition. In the 1950’s Sartre moved towards Marxism and eventually released Critique of Dialectical Reason, Vol. 1 (1960), a massive, systematic account of history and group struggle. In addition to presenting a new critical theory of society based on a synthesis of psychology and sociology, Critique qualified Sartre’s earlier, more radical view of existential freedom. His last systematic work, The Family Idiot (1971), would express his final and most nuanced views on the relation between individuals and social wholes. Sartre’s pioneering combination of Existentialism and Marxism yielded a political philosophy uniquely sensitive to the tension between individual freedom and the forces of history. As a Marxist he believed that societies were best understood as arenas of struggle between powerful and powerless groups. But as an Existentialist he held individuals personally responsible for vast and apparently authorless social ills. The chief existential virtue—authenticity—would require a person to lucidly examine his or her social situation and accept personal culpability for the choices made in this situation. Unlike competing versions of Marxism, Sartre’s Existentialist-Marxism was based on a striking theory of individual agency and moral responsibility.

In addition to class analysis, Sartre offered critiques of anti-Semitism, racism, violence and colonialism. His theoretical account of oppression re-worked Hegel’s master/slave dialectic, arguing that oppression is a concrete, historical instance of mastery. To oppress another is to attempt to validate one’s sense of self by denying the freedom of another. The self-contradictory nature of oppression led him to the optimistic conclusion that oppression is not an inevitable, ontological condition, but a historical reality that should be contested, through both self-assertion and collective action. As a social-political thinker, Sartre defended a large number of innovative methodological and substantive theses. He steered a middle path between reductive individualism and ontological holism. He answered the perennial question “What defines a social group?” with an ingenious re-working of Hegelian recognition. His account of the fusion and disillusion of social groups remains unique to this day. Both broad and original, Sartre’s social-political theory is one of the great contributions to twentieth century philosophy.

Table of Contents

- Texts

- Hegelian-Marxism

- Freedom

- Oppression

- Engagement

- Ideal Society

- Conclusion

- References and Further Reading

1. Texts

Sartre’s prolific writings span multiple genres and have variously been divided into two or three major phases (early and late; or early, middle and late). Sartre’s political writings began in earnest after World War II. In prewar works like Nausea (La Nausée, 1938) and Being and Nothingness (L’Etre et le Néant, 1943) Sartre wrote almost exclusively about individual psychology, imagination and consciousness. Sartre’s primary goal in these works was to discredit determinism and defend the creativity, contingency and freedom of human action. While Sartre’s prewar works are apolitical and inward, his postwar works are politically engaged and historical. The political shift in Sartre’s thinking is reflected by his adoption of the term “praxis” rather than “consciousness” as the active term in his analysis. Turning away from pure psychology, Sartre’s central concerns in the postwar period become group struggle, oppression and the nature of history.

The main theoretical texts of Sartre’s post-war period are Critique of Dialectical Reason (Critique de la raison dialectique Vol.1, 1960, and Vol. 2, 1985) and The Family Idiot (L’Idiot de la famille, 1971). In addition to these theoretical tomes (both over 1,000 pages), Sartre wrote a large number of political essays, most of which were first published in Modern Times (Les Temps modernes), the journal founded by Sartre and others in 1945. The significant essays have been collected in a ten volume set by Gallimard entitled Situations. Of the four novels and nine major plays Sartre published, many have political content.

While writing frequently and passionately about politics and ethics, Sartre never published a systematic philosophical treatise outlining his political or ethical views. There is no Sartrean equivalent to Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Rousseau’s On the Social Contract, or Mill’s On Liberty. His political philosophy emerges from his situational pieces, which were reactions to contemporary political issues, such as the Algerian and Vietnam Wars, French Anti-Semitism and Soviet communism. Critique of Dialectical Reason is the major work of Sartre’s political phase, and is the closest approximation to a work of traditional political philosophy in his corpus. The main themes of Critique include the nature of social groups, history, and dialectical reason. Critique only briefly addresses the canonical themes of political philosophy, such as the theory of the state, political obligation, citizenship, justice and rights.

2. Hegelian-Marxism

Sartre’s contributions to political philosophy are best understood from within the historical context of Hegelianism and Marxism. His political views were influenced heavily by Hegel. In Being and Nothingness he shows some familiarity with the work of Hegel, but this knowledge was indirect and piecemeal. Sartre did not begin a serious study of Hegel until the late 1940s. Between 1947 and 1948 he composed a series of notebooks outlining his plans for a major work in ethical theory. The surviving notebooks, published posthumously as Notebooks for an Ethics (Cahiers pour une morale, 1982), reveal that he developed his own political views through a dialogue with Hegel and Marx. Above all, Sartre was concerned to rethink the master/slave dialectic of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. In Being and Nothingness he agreed with Hegel that humans struggle against one another to win recognition, but rejected the possibility of transcending struggle through relations of reciprocal, mutual recognition. Sartre thought that all human relations were variations of the master/slave relation (see Being and Nothingness,pp. 471-534). However, in the Notebooks, and in the works published beginning in the late 1940s, he dramatically altered his thinking on master/slave relations. First, he accepted the possibility that struggle could be transcended through mutual, reciprocal recognition. His best example was the collaboration between artists and their audience. Second, he located the struggle for recognition in society and history, not in ontology. Third, Sartre’s historical view of the struggle for recognition allowed him to analyze oppression as a type of domination. Finally, he came to agree that social solidarity was not, as claimed in Being and Nothingness, a mere psychological projection, but an ontological reality, based on ties of recognition. In short, Sartre’s main contributions in social and political philosophy were in large part due to his original adaptation and expansion on the Hegelian ideal of intersubjective recognition.

Some scholars contend that Sartre’s normative ethical assumptions (including, by extension, his political views) were derived from Kant. It is true that his best known work, “Existentialism is a Humanism” (“L’Existentialisme est un humanisme,” 1945), presented a universalization argument similar to Kant’s categorical imperative. However, the majority of his works speak critically of Kant. The influence of Hegel vastly outweighs that of Kant. In the autobiographical film Sartre by Himself (Sartre par lui-même, 1976), Sartre admits a deep dissatisfaction with the popularity of Existentialism is a Humanism, a short lecture that was subsequently turned into a widely-distributed essay. In Notebooks, where Sartre reflects on ethics for an extended period, he rejects Kantian ethics, calling it a form of “slave morality” and an “ethics of demands” (pp. 237-274). While he speaks favorably of a “kingdom of ends,” this phrase refers to a socialist society, not a community governed by Kant’s categorical imperative.

Marx’s influence on Sartre is undeniable. While he identified with the French Left prior to the war, experiences during the war politicized him and motivated the turn to Marxism. Sartre’s Marxism was always accompanied by his existentialism. Overwhelmingly devoted to ontological and phenomenological explanations, he would powerfully describe social reality using Marxist structural analysis. The result was a highly original political theory that, while recognizably Marxist, did not resemble the work of structuralist contemporaries such as Louis Althusser. Sartre described himself as rescuing Marxism from lazy dogmatism (Search for a Method, pp. 21 and 27). Like his contemporaries in Germany at the Frankfurt School for Social Research, he sought to develop a general critical theory of society. While accepting the reality of economic class, he strongly criticized those who reduced all social conflicts and all personal motivations to class. In his political period, Sartre deepened his psychological explanations of human behavior by contextualizing individual action within wide social structures (class, family, nation, and so on). He held that economic class was only one of many important structural factors that explained human action. Vehemently criticizing all forms of social scientific reductionism, he claimed that the human situation includes birth, death, family, nationality, gender, race and body, to name only the most relevant (Anti-Semite and Jew, pp. 59-60). Like later analytic Marxists, he would claim that “objective interests” are insufficient to explain the intentions of individual agents. Class analysis must be combined with personal history.

The massive Critique of Dialectical Reason is Sartre’s defense of the unity of Existentialism and Marxism. He showed that functionalist explanations of social phenomena could be grounded in the intentional states of individual agents. Search for a Method (Question de méthode, 1967), the preface to the French Critique, formulates the “progressive-regressive” method, which melds psychological and sociological explanations of human action. The two major components of the method are a regressive analysis of static social structures such as class, family and era, and a second progressive analysis where complex permutations of structures are explained from the lived perspective of individuals and groups. In his existential biographies, such as those on G. Flaubert, S. Mallarmé, and J. Genet, Sartre applies the progressive-regressive method, arguing that individuals “incarnate” (internalize and express) the major social events, movements and values of their era. His view should not be confused with deterministic Marxism, which holds that individuals are mere pawns in a historical game that would be the same with or without them. Individuals have the power to change history, especially through group struggle.

In addition to its methodological contributions, Critique offers a broad account of history, social groups and mass phenomenon. Sartre’s dialectical theory of society, written in the spirit of Hegel and Marx, holds that group struggle is the animating principle of human history. Pace Hegel, Sartre rejects group minds, arguing that there is a basic ontological distinction between the action of persons (individual praxis) and the action of groups (group praxis) (Critique, pp. 345-8). While groups exhibit collective intentionality, no group is a literal organism. Individuals are ontologically prior to the groups they create. Sartre would label his unique approach to social reality “dialectical nominalism” (Critique, p. 37).

In Critique, social groups are divided into four main types: fusing groups, pledge groups, organizations, and institutions (see “Book II: From Groups to History”). Distinct from genuine groups, social “collectives” are semi-unified gatherings of individuals where collective action and mutual recognition are absent (Critique, p. 254). Under Sartre’s pen these distinctions come to life. His analysis of the Bastille is a case in point. Rioting citizens were transformed from a disorganized collective into a group by internalizing the perspective of government officials who thought the rioters were a coherent movement with a single aim (Critique, pp. 351-5). Throughout Critique Sartre develops his foundational claim that social groups are unified when they internalize threatening features of their environment. A “fraternity-terror” dynamic (Critique, p. 430) exists not only in spontaneous groups, but also in oath-based groups and highly bureaucratic institutions.

The social theory of Critique is a far cry from Being and Nothingness, which had asserted that social groups were mere psychological projections (Being and Nothingness, p.536). Critique introduces a new technical concept, that of “mediating third parties,” to explain the nature of groups above and beyond I-thou relations (pp. 100-9). Mediating third parties are members of groups who temporarily act as external threats (for example, when giving orders) but who subsequently re-enter the group (Critique, p.373). The concept of the mediating third party allows Sartre to extend his theory of interpersonal recognition beyond the fictionalized, abstract encounter between self and other, and better explain the fundamentals of group solidarity.

The direct political implications of Critique’s group theory are ambiguous. One popular, plausible interpretation holds that spontaneous groups (for example, fusing and pledge groups) promote human freedom, while bureaucratic groups (such as organizations and institutions) engender alienation. Characteristically, Sartre uses moral terminology to describe groups, but subsequently distances himself from moral conclusions. Institutions, for example, are “degraded forms of community” where “freedom . . . becomes alienated and hidden from its own eyes.” (Critique, pp. 615 and 591). Nonetheless, any politics consistent with Critique would have to favor spontaneous, decentralized social groups.

The concept of alienation also plays an important role in Sartre’s thinking. In Notebooks he defines alienation as being an “other” to oneself (p. 382). In Critique he uses the terms “serialized” and “atomized” to describe persons who are alienated from one another. Unlike Being and Nothingness, where alienation is depicted as an unavoidable ontological condition, in the later political works alienation is rooted in material scarcity. If material scarcity can be eliminated, then we might enjoy “a margin of real freedom, beyond the production of life” (Search for a Method, p. 34).

For most of his life, Sartre remained at a distance from party politics and articulated his political principles without reference to any existing parties. In 1948, however, he co-founded a short-lived non-Communist leftist party, the Rassemblement Démocratique Révolutionnaire. From 1952 to 1956 Sartre supported but did not join the French Communist Party. Later he became disillusioned by the soviet invasion of Hungary and distanced his vision of socialism from Soviet-style communism. In the last years of his life, Sartre associated himself with Maoist groups and took as a personal secretary the young Jewish-Egyptian Maoist Benny Lévy.

On the whole, Sartre’s contributions to Hegelian-Marxism are substantial. He forcefully argued against deterministic, structuralist versions of Marxism, inserting human subjectivity back into the equation. With a keen eye towards interpersonal relations, he showed that social struggle, whether among classes, races or interest groups, must be understood simultaneously at the psychological and the systemic level. Sartre, more than any Marxist of his generation, exposed the limits of classical Marxism and paved the way for a general critical theory of society.

3. Freedom

The concept of freedom, central to Sartre’s system as a whole, is a dominant theme in his political works. Sartre’s view of freedom changed substantially throughout his lifetime. Scholars disagree whether there is a fundamental continuity or a radical break between Sartre’s early view of freedom and his late view of freedom. There is a strong consensus, though, that after World War II Sartre shifted to a material view of freedom, in contrast to the ontological view of his early period. According to the arguments of Being and Nothingness human freedom consists in the ability of consciousness to transcend its material situation (p. 563). Later, especially in Critique of Dialectical Reason, Sartre shifts to the view that humans are only free if their basic needs as practical organisms are met (p. 327). Let us look at these two different notions of freedom in more depth.

Early Sartre views freedom as synonymous with human consciousness. Consciousness (“being-for-itself”) is marked by its non-coincidence with itself. In simple terms, consciousness escapes itself both because it is intentional (consciousness always targets an object other than itself) and temporal (consciousness is necessarily future oriented) (Being and Nothingness, pp. 573-4 and 568). Sartre’s view that human freedom consists in consciousness’ ability to escape the present is “ontological” in the sense that no normal human being can fail to be free. The subtitle of Being and Nothingness, “An Essay in Phenomenological Ontology,” reveals Sartre’s aim of describing the fundamental structures of human existence and answering the question “What does it mean to be human?” His answer is that humans, unlike inert matter, are conscious and therefore free.

The notion of ontological freedom is controversial and has often been rejected because it implies that humans are free in all situations. In his early work Sartre embraced this implication unflinchingly. Famously, Sartre claimed the French public was as free as ever during the Nazi occupation. In Being and Nothingness, he passionately argued that even prisoners are free because they have the power of consciousness (p. 622). A prisoner, though coerced, can choose how to react to his imprisonment. The prisoner is free because he controls his reaction to imprisonment: he may resist or acquiesce. Since there are no objective barriers to the will, the prison bars restrain me only if I form the will to escape. In a similar example, Sartre notes that a mountain is only a barrier if the individual wants to get on the other side but cannot (Being and Nothingness, p. 628).

Sartre’s ontological notion of freedom has been widely criticized, from both political and ontological standpoints. An important contemporary critic of Sartre’s work was his colleague Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose essay “Sartre and Ultrabolshevism” directly attacked Sartre’s Cartesianism and his ontological conception of freedom (Merleau-Ponty, Adventures of the Dialectic, 1955).

While Sartre never renounced the ontological view of freedom, in later works he became critical of what he then called the “stoical” and “Cartesian” view that freedom consists in the ability to change one’s attitude no matter what the situation (Notebooks, pp. 331 and 387; Critique, pp. 332 and 578 fn). It is an open question whether and how to reconcile the early, ontological conception of freedom with the late, material conception of freedom. However, it is undeniable that in his political phase Sartre adopted a new, material view of freedom. Several points stand out in particular. In later works he never again used the notion of consciousness to characterize human existence, preferring instead the Marxist notion of praxis. Further, he came to emphasize the “situation” (i.e. structural influences) in explaining individual choice and psychology (Anti-Semite and Jew, pp. 59-60). Finally, he criticized all “inward” notions of freedom, claiming that a change of attitude is insufficient for real freedom.

Sartre’s shift to a material conception of freedom was motivated directly by the holocaust and World War II. Anti-Semite and Jew (Réflexions sur la question juive, 1946), published just after the war, was the first of many works analyzing moral responsibility for oppression. The fact that Sartre’s view in Being and Nothingness seemed to leave little room for diagnosing oppression did not stop him from articulating a forceful normative critique of Anti-Semitism. His analysis of oppression would, in fact, use the same dialectical tools as those in the section on “concrete relations with others” in Being and Nothingness. Anti-Semite and Jew argues that oppression is a master/slave relationship, where the master denies the freedom of the slave and yet becomes dependent on the slave (pp. 27, 39 and 135). Sartre modified his notion of “the look” by arguing that only some, not all, interpersonal relations result in alienation and loss of freedom.

Sartre’s new appreciation of oppression as a concrete loss of human freedom forced him to alter his view that humans are free in any situation. He did not explicitly discuss such alterations, though clearly abandoning the view that humans are free in all situations. “[I]t is important not to conclude that one can be free in chains,” and “It would be quite wrong to interpret me as saying that man is free in all situations as the Stoics claimed” (Critique, pp. 578 and 332). Sartre’s basic assumption in his political writings is that oppression is a loss of freedom (Critique, p. 332). Since humans can never lose their ontological freedom, the loss of freedom in question must be of a different sort: oppression must compromise material freedom.

Take the case of the prisoner. The prisoner is ontologically free because she controls whether to attempt escape. On this view, freedom is synonymous with choice. But there is no qualitative distinction between types of choices. If freedom is the existence of choice, then even a bad choice is freedom promoting. As he will put it later, an attacker who gives me the choice of “what sauce to be eaten in” could hardly be said to meaningfully promote my freedom (Notebooks, p. 331). The early view is subject to the charge that if there are no qualitative distinctions between types of choices, then the phenomena of oppression and coercion cannot be recognized.

In Anti-Semite and Jew and Notebooks Sartre implicitly addresses the above criticism, arguing that oppression consists not in the absence of choice, but in being forced to choose between bad, inhumane options (Notebooks, pp. 334-5). Jews in anti-Semitic societies, for example, are forced to choose between self-effacement or caricatured self-identities (Anti-Semite and Jew, pp. 135 and 148). In Critique Sartre uses the example of a labor contract to illustrate the claim that choice is not synonymous with freedom (Critique, pp. 721-2). An impoverished person who accepts a degrading, low wage job for the sake of meeting her basic needs has a choice—she may starve or accept a degrading job—but her choice is inhumane. He does not claim that diffuse social structures like poverty have the literal agency of individual human beings, but that class structure is a “destiny” and we can speak cogently of social forces which exert causality and turn us into “slaves” (Critique, p. 332).

In the political period as a whole Sartre developed his material view of freedom by contrasting the free person with the slave. Though his notion of slavery is derived from Hegel, Sartre, unlike Hegel, diagnosed literal cases like American chattel slavery. Sartre follows Hegel in portraying slavery as a form of “non-mutual recognition” where one person dominates the other psychologically and physically. A slave, he argues, is un-free because he is dominated by a master (Notebooks pp. 325-411). Material freedom requires, therefore, non-domination, or freedom from coercion. He adds that in master/slave relations, the self-conception of the victim and perpetrator are intertwined and distorted; both parties are in “bad faith”; both fail to fully understand their own freedom. Though both perpetrator and victim are in bad faith, only the slave is coerced physically (Notebooks, p. 331).

Sartre’s view of material freedom is independent of any notion of human nature. He consistently rejects the existence of a pre-social human essence or a set of natural human desires (“Existentialism is a Humanism”; Anti-Semite and Jew, p. 49; Search for a Method, pp. 167-181). The material view of freedom assumes a thin set of universal human goods, including positive human goods (food, water, shelter and education) and negative goods (freedom from all of the following: slavery, poverty, discrimination, domination and persecution). While Critique elaborates an economic understanding of human goods (the essential needs are those of the physical organism), elsewhere Sartre defends a wider spectrum of human needs including cultural goods and access to shared values (Notebooks pp. 329-331). In sum, we can say that a person is materially free in Sartre’s sense if (a) she enjoys basic material security; (b) she is un-coerced; and (c) she has access to cultural and social goods necessary for pursuing her chosen projects.

The foregoing definition casts Sartre as an ally of political liberalism, and suggests that material freedom is a version of liberal autonomy. Liberals who defend the primacy of autonomy typically claim that positive notions of freedom assume substantive, controversial conceptions of the good life. Indeed, Sartre’s rejection of human nature and his thin conception of universal human goods are consistent with liberalism. However, Sartre criticizes classical liberalism, especially in Critique, arguing against asocial, atomistic notions of selfhood (p. 311). Further, like civic republican philosophers (such as Aristotle and Rousseau), Sartre contends that controlling the social forces to which one is subject is a valuable type of human freedom. Republican philosophers variously call such freedom “self-government” or “non-domination.” Whether Sartre’s view of freedom is a better fit with contemporary liberalism or civic republicanism is a matter of speculation. Sartre’s discussion of freedom in Critique is highly abstract and does not translate simply into one public policy or another. However, his preference for mass movements and bottom-up social organization suggest that he would favor radical participatory democracy. After the student revolts of May 1968 Sartre told an interviewer: “For me the movement in May was the first large-scale social movement which temporarily brought about something akin to freedom and which then tried to conceive of what freedom in action is” (Life/Situations, p. 52).

4. Oppression

The analysis of oppression is one of Sartre’s most original contributions to political philosophy. Adapting the master/slave dialectic of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, Sartre developed a general theory of oppression that yielded moral critiques of anti-Semitism, colonialism, class bigotry and anti-black racism.

Consistent with his general methodology, Sartre denied that oppression reduces to either individual attitudes or impersonal social structures. Oppression is simultaneously “praxis” (the result of intentional acts) and “process” (a supra-individual phenomenon, irreducible to intentional states of individuals) (Critique,pp. 716-735). Oppression is defined by Sartre as the “exploitation of man by man . . . characterized by the fact that one class deprives the members of another class of their freedom” (Notebooks, p. 562). On the interpersonal level, oppression is a master/slave relationship; the oppressor tries to gain a robust sense of selfhood by dominating others. Sartre, like Hegel, showed that domination is a self-defeating practical attitude. The dominator tries to force others to recognize him as superior; but ironically, the dominator receives little confirmation of his superiority as he has ruled out in advance the weight of others’ judgments (Anti-Semite and Jew, p. 27; see also Simone de Beauvoir’s Ethics of Ambiguity, 1947, especially pp. 60-63). Sartre’s analysis works particularly well at diagnosing attitudes of racial superiority. An anti-Semite bases his self-image on the fact that he is not-a-Jew, but in so doing, he becomes depended upon the Jewish other from whom he claims total independence. Ultimately, the racist receives no satisfaction from domination because he solicits recognition from someone he denigrates.

The concept of bad faith also plays an important role in Sartre’s analysis of oppression. Bad faith is an original notion developed by Sartre, first in Being and Nothingness, and subsequently in Anti-Semite and Jew, Saint Genet and Situations. Despite his quip that bad faith does not imply moral blame, Sartre’s discussions of bad faith are heavily moralistic. Bad faith is a deep confusion about one’s own basic projects, attitudes, desires and actions. Bad faith is self-deception (See Being and Nothingness, pp. 86-119). And just as freedom is the chief value of existentialism, bad faith—misrecognizing one’s freedom—is the chief existential vice. In particular, racists are in bad faith if they believe humans have racial “essences” or “natures” (Anti-Semite and Jew, pp. 17, 20, 27 and 53). Race, Sartre claims, is socially constructed. The biological view of race, which says there are innate racial character traits, causes a host of distortions and misinterpretations of human action. Most fundamentally, the appeal to essences causes us to abdicate responsibility and blame our freely chosen actions on fictitious inner drives and motives. In Notebooks Sartre expanded his analysis of racist bad faith by arguing that all oppression, not just racist oppression, requires bad faith: “One oppresses only if one oppresses himself” (Notebooks, p.325).

Controversially, Sartre claimed that both perpetrators and victims of oppression exhibit bad faith. In Anti-Semite and Jew Sartre distinguished “authentic” from “non-authentic” Jews, arguing that inauthentic Jews (those who either ignore racism or internalize negative stereotypes) are in bad faith (pp. 44, 93, 96, 109 and 136). Existential authenticity, the ethical virtue that opposes bad faith, does not amount to embracing one’s biology or heritage. Rather, authenticity consists in properly affirming one’s own freedom through clarified reflection and responsible action. In Anti-Semite and Jew Sartre defines authenticity as follows:

If it is agreed that man may be defined as a being having freedom within the limits of a situation, then it is easy to see that the exercise of this freedom may be considered as authentic or inauthentic according to the choices made in the situation. Authenticity, it is almost needless to say, consists in having a true and lucid consciousness of the situation, in assuming the responsibilities and risks that it involves, in accepting it in pride or humiliation, sometimes in horror and hate. (p. 90)

While Sartre emphasized the lonely, individualistic aspect of affirming one’s freedom, (especially in early fiction like The Flies [Les Mouches, 1943]), he also explored the intersubjective conditions of authenticity. At times Sartre endorsed the view, held by fellow existentialist Simone de Beauvoir, that a proper relation to one’s own freedom requires affirming the freedom of others (de Beauvoir, The Ethics of Ambiguity, p. 67; Sartre Notebooks, pp. 475–79). In “Existentialism is a Humanism,” Sartre gestured towards the interconnection of human freedoms, claiming that to will one’s own freedom required willing the freedom of others. But only later, in his unpublished writings on ethics did he fully explain his view: “If I grasp my freedom in a fulfilled intuition as both the source of all my projects and requiring universal freedom, I cannot think of destroying the freedom of others” (Notebooks, p. 328). His belief that each person’s freedom is connected to the freedom of others pervades his discussion of oppression in Notebooks.

Critique of Dialectical Reason offers a macro-social phenomenology of oppression. Oppression “serializes” (i.e. disperses and alienates) members of underprivileged collectives (Critique, pp. 721–3). Sartre’s view, while indebted to Marx’s notion of alienation, reflects his own unique blend of Marxism and Existentialism. “By alienation we mean a certain type of relations that man has with himself, with others and with the world, where he posits the ontological priority of the Other” (Notebooks, p. 382). The architecture of Critique as a whole depends on the distinction between alienating (“serial”) and non-alienating (“group praxis”) social relationships. Social relations range from utterly non-unified social “collectives” to groups that exhibit various levels of awareness and reciprocity. Written during the Algerian war, Critique frequently cites French colonialism in Africa as an example of serial, alienating action. Colonialism creates a climate of hostility where each person is alien to himself and alien to other members of his collective (Critique, pp. 716-721). Serialized collectives tend not to organize themselves into resistance groups and tend to lack awareness of their potential group power. For example, desperately impoverished Algerians compete against each other for low wage jobs and unintentionally harm the entire collective by driving down wages for everyone.

Sartre shows, then, that oppression is both an interpersonal dynamic and a social-institutional phenomenon. Adopting Hegel’s master/slave dialectic, he claims that oppressors attempt to validate their own sense of superiority by dominating others. Like Hegel, Sartre sees domination as ultimately self-defeating. To oppress requires implicitly acknowledging the victim’s humanity in order to subsequently revoke it. On the psychological level, the oppressor lives in bad faith, misunderstanding his own freedom and the freedom of his victim. In later works, especially Critique, the psychological portrait of oppression is mapped onto a macro-social analysis of group struggle. Institutionalized racism is seen as a special case of bureaucratic dehumanization. Victims of racist oppression become alienated, both from themselves and from one another, making organized resistance unlikely. Sartre’s lasting contribution to the politics of oppression consists in persuasively combining interpersonal and institutional explanations of oppression.

5. Engagement

Engagement is a specialized term in the Sartrean vocabulary and refers to the process of accepting responsibility for the political consequences of one’s actions. Sartre, more than any other philosopher of the period, defended the notion of socially responsible writing (littérature engagée). Like Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, Sartre argued that intellectuals, as well as ordinary citizens, are responsible for taking a stand on the major political conflicts of their era (What is Literature? p. 38). Somewhat idealistically, he hoped that literature might be a vehicle through which oppressed minorities could gain group consciousness, and through which members of the elite would be provoked into action.

Sartre was famous for writing scathing essays condemning French policies. While he intervened in most major French political issues in his lifetime, his critique of French colonialism in Algeria is the most striking instance of Sartrean engagement. He wrote dozens of essays attacking French colonialism in Algeria, and introduced to the French public works of lesser known political writers. Sartre wrote prefaces for F. Fanon’s study of psychic pathologies caused under French colonialism, Wretched of the Earth (Les damnés de la terre, 1961), H. Alleg’s book on torture in Algeria, The Question (La question, 1958), and A. Memmi’s Colonized and Colonizer (Portrait du colonisé, 1957). His preface to an anthology of black, anti-colonialist poets, A. Césaire and L. Senghor’s “Black Orpheus” (“Orphée Noir,” 1948), extended his theory of engaged literature and contributed to the Negritude movement.

The inaugural issue of Les Temps modernes (October, 1945) first articulated the vision of social responsibility which would become the hallmark of political existentialism. A socially responsible writer must address the major events of the era, take a stance against injustice and work to alleviate oppression. What is Literature? (Qu’est-ce que la literature?, 1947) bases the argument for responsible writing on a phenomenological description of the relationship between reader and writer. Writing is necessarily a dialogical, intersubjective process, where author and reader mutually recognize each other (What is Literature?, p. 58). Mutual respect, Sartre claims, is inherent in the relationship between artist and audience. What is Literature? is a landmark essay because it provides the social-ontological basis for Sartre’s view of mutual recognition and grounds his claim that authentic, engaged action must respect the needs of others.

Sartre’s claim that engagement is an ethical and political virtue begins with the premise that humans are necessarily situated in particular places and times. It is impossible to be politically neutral, he insists (What is Literature?, p. 38). The only honest course is to openly admit and defend one’s political commitments. Engagement is the political version of existential authenticity, which requires affirming one’s freedom within a social context. Authenticity is a wider notion than engagement, since authenticity requires awareness and responsibility with respect to the totality of one’s being, and overcoming bad faith globally. Existential engagement, on the other hand, requires political awareness and responsibility, and overcoming bad faith with respect to political issues.

Sartrean engagement can be usefully compared to common conceptions of moral responsibility. Sartre accepts the notion that a person should be held morally responsible for an action that she intentionally causes. The distinguishing mark of Sartre’s view is his broad extension of the notion of causal responsibility. Sartre holds an extremely demanding view of negative responsibility (responsibility for omissions). Passivity, Sartre claims, is equivalent to activity (Being and Nothingness, p. 707; What is Literature?, pp. 38, 232 and 234; Notebooks, p. 490). Any omitted action is an action for which an agent is culpable. In a variety of works, Sartre uses the case of war to illustrate his view. If I am the citizen of a nation at war then the war is “mine” and I bear a direct, personal responsibility for the action of my government. Sartre’s essay “We Are All Assassins” (“Nous sommes tous des assassins,” 1958) epitomizes his view: average French citizens are all equally culpable for the French government’s action of enforcing the death penalty.

In late works like Critique Sartre combines a demanding account of personal responsibility with the functionalist view that individuals incarnate their environment. The result is a portrait of social responsibility that holds average citizens responsible for diffuse social ills like racism, poverty, colonialism and sexism. Despite the fact that Sartre fell short of offering a detailed analysis of negative responsibility which would vindicate his sometimes exaggerated ascription of individual moral liability for collective harms, his portrait of political responsibility remains one of the most powerful of the twentieth century.

6. Ideal Society

While never presenting a complete portrait of his ideal society (whether in fiction or non-fiction), Sartre was a lifelong advocate of socialism. In interviews late in life Sartre allowed himself to be called an “anarchist” and a “libertarian socialist” (See “Interview with Jean-Paul Sartre” in The Philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre, ed. P.A. Schilpp, p. 21.). Sartre hoped for a society based on two principles: individual freedom and the elimination of material scarcity.

In Notebooks Sartre described himself as developing a “concrete ethics” which would combine normative ethics and political theory (p. 104). The closest equivalent is Hegel’s notion of Sittlichkeit (ethical life), as described in Philosophy of Right. Like Hegel, Sartre claimed that ethics is more a matter of social convention than abstract rule following. Ethics must be lived in the everyday institutions of average citizens. The natural law approach to ethics, Kantianism in particular, is of limited value because of its universal, abstract character. Sartre accepted the Kantian injunction “always treat others as ends” but he vehemently rejected the existence of a single set of inflexible moral commandments governing all ethical situations (Notebooks, p. 258).

By contrast, Sartre wrote favorably of Hegelian ethics. Mirroring Hegel in Philosophy of Right, Sartre claimed that genuinely ethical relations arise from mutual recognition (Notebooks, pp. 274-279). Kant’s formulaic humanism, Sartre claimed, would strip individuals of their particularity. The real source of ethical injunctions—namely, other people—would be obscured behind notions of transcendental human nature and natural law.

In the late 1940’s Sartre coined the term “concrete liberalism” to describe the type of society he favored (Anti-Semite and Jew, p. 147). The main feature of concrete liberalism is that the fundamental regulative ideal of society—mutual respect—would be based on an individual’s particular projects, not on her abstract human nature (Notebooks, p. 140). Rights, for example, would be guaranteed because of a person’s “active participation in the life of society” not by appealing to a “problematical and abstract ‘human nature’” (Anti-Semite and Jew, p. 146). Sartre’s view anticipates the postmodern critique of Enlightenment values such as universal respect.

In Critique Sartre developed a group theory that is consistent with anarchistic-socialism, although he did not explicitly endorse anarchy in that work. The state, Sartre claimed, cannot represent the people because the people are a collective not a group (Critique, pp. 635-42). Only genuine groups can be represented. (Think, for example, of a labor union which has explicit mechanisms for forming policies and collective views). Modern industrialized societies consist of alienated, serially dispersed citizens. In Critique Sartre recommended, implicitly at least, a loose federation of democratically self-organized groups.

In short, ideal society for Sartre would likely consist of an anarchistic-socialist order where individuals would have the resources to pursue their own authentically chosen projects, with little interference from the state or other entrenched powers. Special emphasis would be placed on local, democratic groups which would support the freely chosen projects of authentic individuals.

7. Conclusion

Sartre’s contributions to twentieth century political philosophy are substantial. Sartre developed a unique political vocabulary that combined the personal redemption of existential authenticity with a call for systematic social change. Like Hegel, Sartre argued that freedom is the most central normative value and sought to reconcile the pursuit of individual freedom with the need for social institutions. Sartre’s analysis of colonialism, racism and anti-Semitism eloquently bridged the gap between theory and practice, and significantly enriched the categories of traditional Marxism. Justifiably, Sartre will be long remembered as both a systematic political philosopher and a trenchant social critic.

8. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

The following is a shortlist of Sartre’s most important political works which have been translated into English.

- Anti-Semite and Jew. New York: Schocken, 1988.

- Sartre’s classic analysis of anti-Semitism and his longest discussion of existential authenticity.

- Between Existentialism and Marxism. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1974.

- Includes several pivotal political essays including “A Plea for Intellectuals.”

- Colonialism and Neocolonialism. London: Routledge, 2001.

- A collection of anti-Colonial writings. Includes Sartre’s preface to F. Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth.

- Communists and the Peace. New York: George Braziller, 1968.

- Statement of Sartre’s brief alignment with the French Communist Party.

- “The Condemned of Altona.” New York: Knopf, 1961.

- Explores collective responsibility for the holocaust.

- Critique of Dialectical Reason, Volume 1. London: Verso, 2004.

- The principle theoretical text of Sartrean Existentialist-Marxism. Articulates Sartre’s theory of groups and history.

- Critique of Dialectical Reason, Volume 2. London: Verso, 1991.

- Unfinished volume devoted to the question of whether history can be understood as the result of group struggle.

- “Existentialism is a Humanism” in Existentialism. New York: Philosophical Library, 1947.

- Famous speech in which Sartre suggests that existentialism has an ethics, not unlike Kant’s categorical imperative.

- Ghost of Stalin. New York: George Braziller, 1968.

- Published in 1956, announces Sartre’s break with the French Communist Party over the Soviet invasion of Hungary.

- Hope Now: The 1980 Interviews. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1996.

- Interviews conducted by young Maoist Beny Lévy in the last year of Sartre’s life, suggesting a new Sartrean ethics.

- Life/Situations: Essays Written and Spoken. New York: Pantheon, 1977.

- Contains several important political essays including “Elections: A Trap for Fools.”

- “Materialism and Revolution” in Literary and Philosophical Essays. New York: Crowell-Collier, 1962.

- Describes the liberating potential of human work.

- Notebooks for an Ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1992.

- Posthumously published set of notebooks exploring existential ethics and politics. Includes long discussions of oppression, slavery, Hegel’s master/slave dialectic and Marxism.

- No Exit and Three Other Plays. New York: Vintage Books, 1946.

- Contains “The Flies,” which is a parable about freedom, and “Dirty Hands,” which deals with the ethics of revolutionary violence.

- On Genocide. Boston: Beacon Press, 1968.

- Short article on the American war in Vietnam and the legacy of French colonialism.

- Saint Genet: Actor and Martyr. New York: George Braziller, 1971.

- Sartre’s existential biography of French writer and thief Jean Genet.

- Sartre On Cuba. New York: Ballantine Books, 1961.

- Report of Sartre’s visit to post-revolution Cuba.

- Search for a Method. New York: Vintage Books, 1963.

- Introduction to the longer Critique. Best succinct statement of Sartrean Existentialist-Marxism.

- What Is Literature? and Other Essays. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988.

- The canonical statement of Sartrean engaged literature. Contains “Black Orpheus,” a defense of the “negritude” poetry of Césaire and Senghor, as well as the inaugural essay for Sartre’s journal Les Temps modernes.

b. Secondary Sources

The following secondary sources on Sartre’s political and ethical thinking are also recommended.

- Anderson, Thomas C., 1993, Sartre’s Two Ethics: From Authenticity to Integral Humanity, Chicago: Open Court.

- Anderson, Thomas C., 1979, The Foundation and Structure of Sartrean Ethics, Lawrence: Regents Press of Kansas.

- Aron, Raymond, 1975, History and The Dialectic of Violence: An Analysis of Sartre’s Critique de la Raison Dialectique, New York: Harper and Row.

- Aronson, Ronald, 1987, Sartre’s Second Critique, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bell, Linda A., 1989, Sartre’s Ethics of Authenticity, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Catalano, Joseph, 1986, A Commentary on Jean-Paul Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reason, vol. 1, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Charmé, Stuart Zane, 1991, Vulgarity and Authenticity: Dimensions of Otherness in the World of Jean-Paul Sartre, Amherst: University of Mass Press.

- Chiodi, Pietro, 1978, Sartre and Marxism, Sussex: Harvester.

- Detmer, David, 1988, Freedom as a Value: A Critique of the Ethical Theory of Jean-Paul Sartre, La Salle: Open Court.

- Dobson, Andrew, 1993, Jean-Paul Sartre and the Politics of Reason, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Flynn, Thomas R., 1984, Sartre and Marxist Existentialism: The Test Case of Collective Responsibility, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Flynn, Thomas R., 1997, Sartre, Foucault and Historical Reason, vol. 1: Toward an Existentialist Theory of History, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Heter, T. Storm, 2006, Sartre’s Ethics of Engagement: Authenticity and Civic Virtue, London: Continuum.

- Jeanson, Francis, 1981, Sartre and the Problem of Morality, tr. Robert Stone, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Martin, Thomas, 2002, Oppression and the Human Condition: An Introduction to Sartrean Existentialism, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

- McBride, William Leon, 1991, Sartre’s Political Theory, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, 1973, Adventures of the Dialectic, trans. Joseph Bien, Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Murphy, Julien S. (ed), 1999, Feminist Interpretations of Jean-Paul Sartre, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Santoni, Ronald E., 2003, Sartre on Violence: Curiously Ambivalent, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Stone, Robert and Elizabeth Bowman, 1986, “Dialectical Ethics: A First Look at Sartre’s unpublished 1964 Rome Lecture Notes,” Social Text nos. 13-14 (Winter-Spring, 1986), 195-215.

- Stone, Robert and Elizabeth Bowman, 1991, “Sartre’s ‘Morality and History’: A First Look at the Notes for the unpublished 1965 Cornell Lectures” in Sartre Alive, ed. Ronald Aronson and Adrian van den Hoven, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 53-82.

Author Information

Storm Heter

Email: sheter@po-box.esu.edu

East Stroudsburg University

U. S. A.