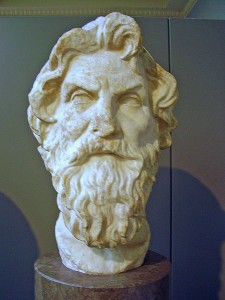

Antisthenes (c. 446—366 B.C.E.)

Known in antiquity as an accomplished orator, a companion of Socrates, and a philosopher, Antisthenes presently gains renown from his status as either a founder or a forerunner of Cynicism. He was the teacher to Diogenes of Sinope, and he is regarded by Diogenes Laertius as the first Cynic philosopher. He is credited with the authorship of over sixty titles, appears as one of the primary interlocutors in Xenophon’s Memorabilia and Symposium, and is mentioned as one of those present at Socrates’ death by Plato, with whom it seems he had a falling out. Antisthenes’ philosophical interests engage ethics rather than metaphysics or epistemology, and he advocates the practice of virtue through an ascetic life and the cultivation of wisdom. Like Socrates before him, Antisthenes adheres to ethical intellectualism, and like the Stoics who follow the Cynics, he claims that virtue is sufficient for happiness.

Known in antiquity as an accomplished orator, a companion of Socrates, and a philosopher, Antisthenes presently gains renown from his status as either a founder or a forerunner of Cynicism. He was the teacher to Diogenes of Sinope, and he is regarded by Diogenes Laertius as the first Cynic philosopher. He is credited with the authorship of over sixty titles, appears as one of the primary interlocutors in Xenophon’s Memorabilia and Symposium, and is mentioned as one of those present at Socrates’ death by Plato, with whom it seems he had a falling out. Antisthenes’ philosophical interests engage ethics rather than metaphysics or epistemology, and he advocates the practice of virtue through an ascetic life and the cultivation of wisdom. Like Socrates before him, Antisthenes adheres to ethical intellectualism, and like the Stoics who follow the Cynics, he claims that virtue is sufficient for happiness.

Table of Contents

1. Life and Works

It is primarily through Xenophon’s dialogues and Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of Eminent Philosophers that certain aspects of Antisthenes’ life and thought are known. These sources are not, however, without problems: Xenophon is portraying Antisthenes as an interlocutor, which leads some scholars to question whether this character is in fact representative of the historical Antisthenes; Diogenes Laertius is thought of as a dubious source due to his penchant for recounting contradictory stories from multiple sources. Though each source is questionable independently, when they are treated in conjunction they provide a sketch of Antisthenes as both a Socratic and a Cynic thinker.

Born probably in either 446 or 445 B.C.E. of an Athenian father, also named Antisthenes, and a Thracian mother, Antisthenes was a nothos, which means literally someone born of an illegitimate union (due to being born from a slave, foreigner, or prostitute, or because one’s parents were citizens but not legally married) and therefore was not an Athenian citizen. Initially he was a pupil of Gorgias the rhetorician, and the rhetorical sounding titles that are ascribed to him by Diogenes Laertius almost certainly derive from this first phase of his career. In fact, of his prolific literary corpus, only his Ajax and Odysseus are extant, and both offer a demonstration of his rhetorical training under Gorgias.

After meeting Socrates and deriving great benefit from him, Antisthenes abandoned his study of rhetoric for philosophy and even encouraged his own pupils to join him under Socrates’ tutelage. His close friendship with Socrates is well documented in Xenophon’s dialogues, and his importance would have been aided by his position as an older and esteemed member of Socrates’ circle. In the years immediately following Socrates’ death, then, it is likely that Antisthenes was regarded as Socrates’ most important follower (see Kahn 4-5).

What little is known about Antisthenes’ life is marked by both his asceticism and humor. It is claimed that he was the first to double his cloak in order to sleep in it, and recommended this to Diogenes of Sinope (though Diogenes of Sinope is also claimed to be the first to do so) and that, in addition, he was equipped with those elements that would later be distinctive of the Cynics: the wallet and the staff. He chose to live in poverty, and more than one of the surviving anecdotes surrounds the ragged state of his cloak, usually involving those areas where the cloak is torn. In addition to eschewing luxuries so many of his fellow Athenians sought, he demonstrated an ad hoc and improvisational sense of humor which allowed him to ridicule commonly held beliefs and the mores of Athenian culture, a practice which would be perfected by Diogenes of Sinope.

2. Basic Tenets

Xenophon’s treatment of Antisthenes combines well with the details Diogenes Laertius provides of his philosophical position at 6.10-12. Though the list of his “favorite themes” is lengthy, it represents the central aspects of his ethical thought. In sum, the basic tenets are:

- Virtue can be taught.

- Only the virtuous are noble.

- Virtue is itself sufficient for happiness, since it requires “nothing else except the strength of a Socrates” (D.L. 6.11).

- Virtue is tied to deeds and actions, and does not require a great deal of words or learning.

- The wise person is self-sufficient.

- Having a poor reputation is something good, and is like physical hardship.

- The law of virtue rather than the laws established by the polis will determine the public acts of one who is wise.

- The wise person will marry in order to have children with the best women.

- The wise person knows who are worthy of love, and so does not disdain to love.

These themes, revolving as they do around virtue and the activity of the wise man, bear an unmistakable resemblance to Socrates’ convictions. The teachability of virtue, the emphasis on deeds over words, and the prominence of erōs are all explicitly found in Socratic literature. Furthermore, according to Diocles, Antisthenes held virtue to be the same for men as for women, a position that is echoed, if in a more inchoate form, in Socratic thought.

Antisthenes’ ethical views also, however, represent an innovation, and do not merely repeat those held by Socrates. First, the unambiguous statement of virtue as sufficient for happiness is a shift from Socrates’ hedging on this matter. Virtue and happiness are completely coincident and open to all. Second, he begins to separate morality and legality in a way that Socrates apparently did not. In Plato’s Crito, Socrates is clear that one is morally obliged to abide by the laws of one’s state, unless one can convince the state to change the laws. The Cynics show no such regard for nomos, a term which means both law and convention, whether it is in relation to cultural codes or legal regulations. By loosening law and virtue Antisthenes sets the stage for the more radical positions of Diogenes of Sinope and Crates.

Antisthenes takes a stronger position than did Socrates on the abstention from physical pleasures, claiming, he says, to prefer madness to pleasure (D.L. 6.3). The pursuit of pleasure is dangerous insofar as it can recommend precarious activities (as is recounted in the story of an adulterer fleeing for his life who Antisthenes claims could have escaped peril “at the price of an obol,” but more importantly, its effect on self-sufficiency is ruinous. One can become enslaved to pleasure and so lose all hope of being truly free. For this reason “When someone extolled luxury his reply was, ‘May the sons of your enemies live in luxury’” (D.L. 6.8).

Finally, he is much more obviously anti-theoretical than Socrates. Whereas Socrates claims to know nothing of theoretical philosophy, Antisthenes suggests that it is useless. Though the terms are not yet coined, the distinction is between metaphysics and ethics, and Antisthenes focuses upon the latter only. His privileging of practice over learning, or deeds over words, is clearly anti-theoretical, but it should not be viewed as opposed to reason. Reason, for Antisthenes, is the foundation of virtue. “Wisdom is a most sure stronghold which never crumbles away nor is betrayed. Walls of defense must be constructed in our own impregnable reasonings” (D.L. 6.13). Antisthenes’ caution against pleasure, his praise of poverty, and his privileging of reason will be palpable in the Cynics who follow him and Stoic cultivation of indifference.

3. Philosophical Influence

Antisthenes’ influence is primarily upon the “school” of Cynicism, both as a precursor and originator. Antisthenes’ life and thought provide a connection between Socrates and the Cynics. Diogenes Laertius makes just this point: “From Socrates he learned his hardihood, emulating his disregard of feeling, and thus he inaugurated the Cynic way of life”(D.L. 6.2). Some scholars are more dubious. Dudley, for example, claims that Antisthenes was a follower of Socrates, and nothing more. The attribution of “first Cynic” to Antisthenes is, on Dudley’s account, merely an invention of the Alexandrian writers of Successions meant to give the Stoic school the proper Socratic pedigree.

Branham and Goulet-Cazé propose that Antisthenes be considered a “forerunner” (The Cynics 7), and Navia claims that “in both Antisthenes and Diogenes we come upon one reaction to the problem of human existence, and one radical solution… for Cynicism emerged among the Greeks from both, as if from twin sources” (Classical Cynicism 67). The subtler approaches of Branham, Goulet-Cazé, and Navia grasp the impossibility of resolving the debate. The sources of antiquity have combined the tradition of Diogenes with that of Antisthenes. Thus, the Cynic movement is viewed as having begun with the Socratic ethical practices of Antisthenes, practices which receive their more robust instantiations through the life of Diogenes of Sinope.

The claim that Antisthenes had no connection to the Cynics is, given Antisthenes’ unique ethical position, tenuous. Antisthenes endorses the Socratic position, but contributes his own understanding of virtue and his insistence upon the importance of askēsis. His asceticism is comparable to that of Socrates, but his animosity toward pleasure and his pride in his poverty resembles better the position of later Cynics. Finally, the privileging of virtue and the claim that virtue is itself sufficient for happiness will be central to Stoic ethics. “Antisthenes gave the impulse to the indifference of Diogenes, the continence of Crates, and the hardihood of Zeno, himself laying the foundations of their state” (D.L. 6.15).

4. References and Further Reading

- Billerbeck, Margarethe. Die Kyniker in der modernen Forschung. Amsterdam: B.R. Grüner, 1991.

- Branham, Bracht and Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé, eds. The Cynics: The Cynic Movement in Antiquity and Its Legacy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

- Dudley, D. R. A History of Cynicism from Diogenes to the 6th Century A.D. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1937.

- Goulet-Cazé, Marie-Odile and Richard Goulet, eds. Le Cynisme ancien et ses prolongements. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1993.

- Kahn, Charles H. Plato and the Socratic Dialogue: The Philosophical Use of a Literary Form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Diogenes Laertius. Lives of Eminent Philosophers Vol. I-II. Trans. R.D. Hicks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- Long, A.A. and David N. Sedley, eds. The Hellenistic Philosophers, Volume 1and Volume 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Malherbe, Abraham J., ed. and trans. The Cynic Epistles. Missoula, Montana: Scholars Press, 1977.

- Navia, Luis E. Classical Cynicism: A Critical Study. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1996.

- Navia, Luis E. Antisthenes of Athens. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2001.

- Paquet, Léonce. Les Cyniques grecs: fragments et témoignages. Ottawa: Presses de l’Universitaire d’Ottawa, 1988.

Author Information

Julie Piering

Email: japiering@ualr.edu

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

U. S. A.