Propositional Attitudes

Sentences such as “Galileo believes that the earth moves” and “Pia hopes that it will rain” are used to report what philosophers, psychologists, and other cognitive scientists call propositional attitudes—for example, the belief that the earth moves and the hope that it will rain. Just what propositional attitudes are is a matter of controversy. In fact, there is some controversy as to whether there are any propositional attitudes. But it is at least widely accepted that there are propositional attitudes, that they are mental phenomena of some kind, and that they figure centrally in our everyday practice of explaining, predicting, and rationalizing one another and ourselves.

For example, if you believe that Jay desires to avoid Sally and has just heard that she will be at the party this evening, you may infer that he has formed the belief that she will be at the party and so will act in light of this belief so as to satisfy his desire to avoid Sally. That is, you will predict that he will not attend the party. Similarly, if I believe that you have these beliefs and that you wish to keep tabs on Jay’s whereabouts, I may predict that you will have made the prediction that he will not attend the party. We effortlessly engage in this sort of reasoning, and we do it all the time.

If we take our social practices at face value, it is difficult to overstate the importance of the attitudes. It would seem that, without the attitudes and our capacity to recognize and ascribe them, as Daniel Dennett colorfully puts it, “we could have no interpersonal projects or relations at all; human activity would be just so much Brownian motion; we would be baffling ciphers to each other and to ourselves—we could not even conceptualize our own flailings”.

In fact, if we follow this line of thought, it seems right to say that we would not even be baffled. Nor would we have selves to call our own. So central, it seems, are the attitudes to our self-conception and so effortlessly do we recognize and ascribe them that one could be forgiven for not realizing that there are any philosophical issues here. Still, there are many. They concern not just the propositional attitudes themselves but, relatedly: propositional attitude reports, propositions, folk psychology, and the place of the propositional attitudes in the cognitive sciences. Although the main focus of this article is the propositional attitudes themselves, these other topics must also be addressed.

The article is organized as follows. Section 1 provides a general characterization of the propositional attitudes. Section 2 describes three influential views of the propositional attitudes. Section 3 describes the primary method deployed in theorizing about the propositional attitudes. Section 4 describes several views of the nature of folk psychology and the question of whether there are in fact any propositional attitudes. Section 5 briefly surveys work on a range of particular mental phenomena traditionally classified as propositional attitudes that might raise difficulties for the general characterization of propositional attitudes provided in Section 1.

Table of Contents

- General Characterization of the Propositional Attitudes

- Three Influential Views of the Propositional Attitudes

- Propositions, Propositional Attitude Reports, and the Method of Truth in Metaphysics

- Folk Psychology and the Realism/Eliminativism Debate

- More on Particular Propositional Attitudes, or on Related Phenomena

- References and Further Reading

1. General Characterization of the Propositional Attitudes

This section provides a general characterization of the propositional attitudes.

a. Intentionality and Direction of Fit

The propositional attitudes are often thought to include not only believing, hoping, desiring, predicting, and wishing, but also fearing, loving, suspecting, expecting, and many other attitudes besides. For example: fearing that you will die alone, loving that your favorite director has a new movie coming out, suspecting that foreign powers are meddling in the election, and expecting that another recession is on the horizon. Generally, these and the rest of the propositional attitudes are thought to divide into two broad camps: the belief-like and the desire-like, or the cognitive ones and the conative ones. Among the cognitive ones are included believing, suspecting, and expecting; among the conative ones are included desiring, wishing, and hoping.

It is common to distinguish these two camps by their direction of fit, whether mind-to-world or world-to-mind (Anscombe 1957[1963], Searle 1983, 2001, Humberstone 1992). If an attitude has a mind-to-world direction of fit, it is supposed to fit or conform to the world; whereas if it has a world-to-mind direction of fit, it is the world that is supposed to conform to the attitude. The distinction can be put in terms of truth conditions or satisfaction conditions. A belief is true if and only if the world is the way it is believed to be, and is otherwise false; a desire is satisfied if and only if the world comes to be the way it is desired to be, and is otherwise unsatisfied. (In this respect, beliefs are akin to assertions or declarative sentences and desires to commands or imperative sentences.) In both cases, the attitude is in some sense directed at the world.

Accordingly, the propositional attitudes are said to be intentional states, that is, mental states which are directed at or about something. Take belief. If you believe that the earth moves, you have a belief about the earth, to the effect that it moves. More generally, if you believe that a is F, you have a belief about a, to the effect that it is F. The state of affairs a being F might also be construed as what one’s belief is about. That a is F is then the content of one’s belief, to wit, the proposition that a is F. One’s belief is true if and only if a is indeed F, that is, if the state of affairs a being F obtains. On common usage, an obtaining state of affairs is a fact.

(On various deflationary theories of truth, either there cannot be or there is no need for a substantive theory of facts. However, all that is required here is a very thin sense of fact. To admit the existence of facts, in this relevant thin sense, one needs only to accept that which propositions are true depends on what the world is like. To be sure, the recognition of true modal, mathematical, and moral claims, among others, raises many vexing questions for any attempt to provide a substantive theory of facts; but we can set these aside. No particular metaphysics of facts is here required. For further discussion, see the articles on truth, truthmaker theory, and the prosentential theory of truth.)

Of course, not every proposition is about some particular object. Some are instead general: for example, the proposition that whales are mammals, or the proposition that at least one person is mortal. All the same, there are some conditions that must obtain if these general propositions are to be true. If these conditions do not obtain, the propositions are false. If one believes that whales are mammals, one’s belief is true if and only if it is a fact that whales are mammals; and if one believes that at least one person is mortal, one’s belief is true if and only if it is a fact that at least one person is mortal.

According to many theorists, it is constitutive of belief that one intends to form true beliefs and does not hold a belief unless one takes it to be true (Shah and Velleman 2005). That is, on such a view, if one’s mental state is not, so to speak, governed or regulated by the norm of truth, it is not a belief state. Indeed, the idea is sometimes put in explicitly normative terms: one ought to form true beliefs, and one ought not to hold a belief unless it is true (Wedgwood 2002). It is thus sometimes said that belief aims at truth.

Desire is often said to work similarly. If you desire, for example, that you be recognized by your teammates for your contributions to the team, this desire will go unsatisfied unless and until the world becomes such that you are recognized by your teammates for your contributions to the team. Often, if not always, one desires what one perceives or believes to be good. Thus, it is sometimes said that while belief aims at what is (believed to be) true, desire aims at what is (perceived or believed to be) good. In one form or another, this view has been held by major figures like Plato, Aristotle, and Immanuel Kant.

b. Conscious and Unconscious Attitudes

Famously, Franz Brentano characterized intentionality as the “mark of the mental,” that is, as a necessary and sufficient condition for mentality. On some views, all intentional states are propositional attitudes (Crane 2001). Putting these two views together, it would follow that all mental states are propositional attitudes (Sterelny 1990). Other philosophers hold that there are intentional states that are not propositional attitudes (see Section 5). On still other views, there are non-intentional, qualitative mental states. Candidates include sensations, bodily feels, moods, emotions, and so forth. What is distinctive of these latter mental states is that there is something it is like to be in them, a property widely considered as characteristic of phenomenally conscious states (Nagel 1974). Most theorists have written as if the propositional attitudes do not have such qualitative properties. But others claim that the attitudes, when conscious, have a qualitative character, or a phenomenology—to wit, a cognitive phenomenology.

Some theorists have claimed that there is a constitutive connection between consciousness and mentality: mental states must be at least potentially conscious (Searle 1992). Other theorists, including those working in computational psychology, allow that some mental states might never be conscious. For example, the sequences of mental states involved in processing visual information or producing sentences may not be consciously accessible, even if the end products are. Perhaps, similarly, some propositional attitudes (possessed by some subject) are—and will always be—unconscious.

For example, if linguistic competence requires knowledge of the grammar of the language in question, and knowledge is (at least) true belief, then linguistic competence involves certain propositional attitudes. (This conditional is controversial, but it will still serve as an illustration. See Chomsky 1980.) Manifestly, however, being linguistically competent does not require conscious knowledge of the grammar of one’s language; otherwise, linguistics would be much easier than it is. Consider, for another example, the kind of desires postulated by Freudian psychoanalysis. Suppose, at least for the sake of argument, that this theory is approximately correct. Then, some attitudes might never be conscious without the help of a therapist.

Other attitudes might sometimes be conscious, other times not. For example, for some period of months before acting on your desire, you might desire to propose to your partner. You have the desire during this time, even if you are not always conscious of it. Similarly, you might for most of your life believe that the thrice-great grandson of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was born in Louisville, KY, even if the circumstances in which this belief plays any role in your mental life are few and far between.

With these observations in mind, some theorists distinguish between standing or offline attitudes and occurrent or online attitudes. When, for example, your desire to propose to your partner and your belief that now is a good time to do it conspire in your decision to propose to your partner now, they are both online. Occurrent or online attitudes might often be conscious, but not always. Sometimes others are in a better position to recognize your own attitudes than you are. This seems especially likely to be the case when it would embarrass or pain us to realize what attitudes we have.

c. Reasons and Causes

Talk of combinations of beliefs and desires leading to action or behavior might suggest that propositional attitudes are causes of behavior; and this is, in fact, the dominant view in the philosophy of mind and action of the beginning of the 21st century. One common way of construing the notion of online attitudes is in causal terms: to say that an attitude is online is to say that it is constraining, controlling, directing, or in some other way exerting a causal influence on one’s behavior and other mental states. But standing attitudes might also be construed as causes of a kind. For example, Fred Dretske (1988, 1989, 1993) speaks of attitudes generally as “structuring causes”, in contrast to “triggering causes”. I might, for example, have a desire, presumably innately wired into me, to quench my thirst when thirsty. This, alongside a belief about how to go about quenching my thirst, might serve as a structuring cause which, when thirsty (a triggering cause), causes me to go about quenching my thirst.

Of course, sometimes when I am thirsty, have a desire to quench my thirst, and have a belief about how I might go about doing that, I remain fixed to the couch. In this case, barring some physical impediment, it is likely that I have some other desire stronger than the desire to quench my thirst. Just how much influence an attitude has on one’s behavior and other mental states may vary with its strength. Someone might, for another example, desire to lose weight, but not as much as they desire to eat ice cream. In this case, when presented with the opportunity to eat ice cream, they will, all else being equal, be more likely to engage in ice-cream eating than not. If we have information about the relative strengths of their desires, our predictions will reflect this. If our predictions prove correct, we have reason to think that we have in hand an explanation of their behavior—to wit, a causal explanation.

At least, this is how a causalist will put it. But belief-desire combinations are also said to constitute reasons for action, and on some views, reasons are not causes. Suppose, for example, that Mr. Xi starts to go to the fridge for a drink. We ask why. The reply: Because I am thirsty and there is just the fix in the fridge. It is generally agreed that what Xi supplies is a reason for doing what was done. He cites a desire to quench his thirst and a belief about how he might go about doing that. The causalist claims that this reason is also the cause of the behavior. But the anti-causalists deny that this reason is a cause, and for this reason they deny that rationalization is a species of causal explanation. Instead, rationalizations are for making sense of or justifying behaviors. Although this view was widely held in the first half of the 20th century, largely under the influence of Ludwig Wittgenstein and Elizabeth Anscombe, the dominant view at the beginning of the 21st century—owing largely to Donald Davidson—is that rationalizations are a species of causal explanation. Where one sides in this dispute may depend in part on the position one takes on folk psychology, which supplies the framework for rationalizations. We return to this in Section 4.

2. Three Influential Views of the Propositional Attitudes

This section describes three influential views of the propositional attitudes.

a. The Classical View

Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell did the most to put the propositional attitudes on the map in analytic philosophy. In fact, Russell is often credited with coining the term, and they both articulate what we might call the Classical View of propositional attitudes (although Russell, whose views on these matters changed many times, does not everywhere endorse it). (See, for example, Frege 1892 [1997], 1918 [1997], Russell 1903.) On this view, attitudes are mental states in which a subject is related to a proposition. They are, therefore, psychological relations between subjects and propositions. It follows from this that propositions are objects of attitudes, that is, they are what one believes, desires, and so on.

Propositions are also the contents of one’s attitudes. For example, when Galileo asserts that the earth moves, he expresses a belief (assuming, of course, that he is sincere, understands what he says, and so forth), namely the belief that the earth moves. What Galileo believes is that the earth moves. So, it is said that the content of Galileo’s belief, which may be true or false, is that the earth moves. This is precisely the proposition that the earth moves, reference to which we secure not only with the expression “the proposition that the earth moves” but also with “that the earth moves”.

Propositions, on this view, are the primary truth-bearers. If a sentence or belief is true, this is because the sentence expresses (or is used to express) a true proposition or because the belief has as its object and content a true proposition. It is in virtue of being related to a proposition that one’s belief can be true or false, as the case may be. As they may be true or false, propositions have truth conditions. They specify the conditions in which they are true, that is, the conditions or states of affairs that must obtain if the proposition is to be true—or, to put it in still another way, what the facts must be.

Propositions have their truth conditions absolutely, in the sense that their truth conditions are not relativized to the sentences used to express them. In using the sentence “the earth moves” to assert that the earth moves, we express the proposition that the earth moves and thus our belief that the earth moves. Galileo expressed this belief, too. Thus, we and Galileo believe the same thing and may therefore be said to have the same belief. Presumably, however, Galileo did not express his belief in English. He might have instead used the Italian sentence, “La terra si muove”. There are, of course, indefinitely many sentences, both within and across languages, that may be used to express one and the same proposition. (It might be said that sentences are inter-translatable if and only if they express the same proposition.) No matter which sentence is used to express a proposition, its truth conditions remain the same.

Propositions also have their truth conditions essentially, in the sense that they have them necessarily. Necessarily, the proposition that the earth moves (which can, again, be expressed with indefinitely many sentences) is true if and only if the earth moves. The proposition does not have these truth conditions contingently or accidentally; it is not the case that it might have been true if and only if, say, snow is white. (On some views, the sentence “the earth moves” might have expressed the proposition that snow is white, or some other proposition; but that is a different matter.) In the language of possible worlds, often employed in the discussion of modal notions like necessity and possibility: there is no possible world in which the proposition that the earth moves has truth conditions other than those it has in the actual world.

(Incidentally, though this is not something discussed by Frege and Russell, propositions are often said to be the primary bearers of modal properties, too. It is said, for example, that if it is necessary that 7 + 5 = 12, the proposition that 7 + 5 = 12 is necessary. It is, in other words, a necessary truth, where a truth is understood to be a true proposition. In the language of possible worlds: it is true in every possible world.)

We can, as already mentioned, share beliefs, and this means, on the going view, that one and the same proposition may be the object of our individual beliefs. This raises the question of what propositions could be, such that individuals as spatiotemporally separated as we and Galileo could be said to stand in relation to one and the same proposition. Frege’s answer, as well as Russell’s in some places, is that they must be mind- and language-independent abstract objects residing in what Frege called the “third realm”, that is, neither a psychological realm nor the physical realm (the realm of space and time). In other words, Frege (and again, Russell in some places) adopted a form of Platonism about propositions, or thoughts (Gedanken) as Frege called them.

To be sure, this view invites difficult questions about how we could come into contact with or know anything about these objects. (Being outside space, it is not even clear in what sense propositions could be objects.) It is generally assumed that whatever can have causal effects must be concrete, that is, non-abstract. It follows from this assumption that propositions, as abstract objects, are not just imperceptible but causally inefficacious. That is, they can themselves have no causal effects, whether on material objects or minds (even if minds are non-physical, as Frege thinks). Frege acknowledges this last observation but insists that, somehow, we do in some sense grasp or apprehend propositions.

In the philosophy of mathematics, serious worries have been raised about how we might gain knowledge of mathematical objects if they are as the Platonist conceives of them (see, for example, Benacerraf 1973), and the same would seem to go for propositions. The difficulty is compounded if, following Frege, we conceive of the mind as non-physical or non-concrete. The concrete is generally conceptualized as the spatiotemporally located. Thus to define the ‘abstract’ as the non-concrete is to define the abstract as the non-spatiotemporally located. On Frege’s view, the mind is not spatiotemporally located, concrete, or physical. And yet, presumably, it is not abstract. What’s more, there seem to be mental causes and effects, for one idea leads to another. In fact, as Frege acknowledges, ideas can bring about the acceleration of masses.

Frege nowhere presents a detailed view of these matters, so it is not clear that he had one. In general, it is not clear what a satisfactory view of propositions as abstract objects would look like. So perhaps it can be understood why, as early as 1918, Russell (despite his important role in developing the theory of propositions) would take the position that “obviously propositions are nothing”, adding that no one with a “vivid sense of reality” can think that there exists “these curious shadowy things going about”. Nevertheless, it is not clear that Russell manages to do without them. In fact, few have so much as attempted to do without them—the nature of propositions being a lively area of research. We return to a discussion of propositions in 3b.

b. Dispositionalism

Dispositionalism, most broadly construed, is the view that having an attitude, for example the belief that it is raining, is nothing more than having a certain disposition, or set of dispositions, or dispositional property or properties. On the simplest dispositionalist view—held by many philosophers when behaviorism was the dominant paradigm in psychology and logical positivism was the reigning philosophy of science (roughly, the first half of the 20th century)—the relevant dispositions are dispositions to overt, observable behavior (Carnap 1959). On this view, to lay stress on the point, to believe that it is raining just is to have certain behavioral dispositions, as exhibited in certain patterns of overt, observable behavior.

Dispositionalists and non-dispositionalists alike agree that patterns of behavior, being manifestations of behavioral dispositions, are evidence for particular beliefs and other attitudes an agent has. However, dispositionalists claim that there is nothing more to the phenomenon: if one were to have exhaustively specified the behavioral dispositions associated with the ascription of the belief that it is raining, one would have said everything there is to say about this belief. In this sense, dispositionalism is a superficial view: in ascribing an attitude, we do not commit ourselves to the existence of any particular internal state of the agent in possession of the attitude—whether a state of the mind or brain. Having an attitude is a surface phenomenon, a matter of how one conducts oneself in the world (Schwitzgebel 2013, Quilty-Dunn and Mandelbaum 2018).

Notoriously, it is very difficult to provide any informative general dispositional characterization of an attitude, such as the belief that it is raining. To take a stock example, we might say that if one believes that it is raining, one will be disposed to carry an umbrella when one leaves the house. Evidently, this will require not only that one has an umbrella on hand but that one desires not to get wet, remembers where the umbrella is located, believes that it will help one to stay dry, and so on. In general, as many theorists have observed, it seems that the behavioral dispositions associated with a particular attitude are not specifiable except by reference to other attitudes (Chisholm 1957, Geach 1957). This is sometimes referred to as the holism of the mental.

This is a problem for the simple dispositional accounts which seek to reduce or analyze away all mental talk into behavioral talk. Such a reductive project was pursued, or at least sketched, by the logical behaviorists, who wished—by analyzing talk of the mind into talk of behavior—to pave the way toward reducing all mental descriptions to physical descriptions. The view was thus a form of physicalism, according to which the mental is physical. Thus, it was sometimes said that mental state attributions are really but shorthand for descriptions of behavioral patterns and dispositions. According to the logical behaviorists, logical analysis was to reveal this. However, it is generally agreed that this project, articulated most influentially by Carl Hempel (1949) and Rudolph Carnap (1959), failed—and precisely on account of the holism of the mental. (There are no prominent logical behaviorists in the 21st century. Carnap and Hempel themselves abandoned the project after having rejected the verificationist criterion of meaning at the heart of logical positivism. According to this criterion, all meaningful empirical statements are verifiable by observation. In the case of psychological statements, the thought was that they should be verifiable by observation of overt behavior. For further discussion, see the articles linked to in the preceding paragraphs of this subsection.)

The holism of the mental is not, however, a problem for every simple dispositionalist account of the propositional attitudes, for not every such account has reductive ambitions. For some, it is enough that we can provide a dispositional characterization of each mental state attribution, albeit one involving reference to other mental states. For example, one might be said to remember where the umbrella is located if one is able to locate it—say, when one wants the umbrella (because, we might add, one desires not to get wet and believes that the umbrella will help one to stay dry). Similarly, one might be said to desire to stay dry if, when one believes that it is raining, one is disposed to adopt some rain-avoiding behavior: say, not leaving the house, or not leaving the house without an umbrella (if one believes that it will help one to stay dry). Despite the difficulty of providing informative general dispositional characterizations of attitudes, everyone semantically competent with the relevant stretches of language is adept at recognizing and ascribing attitudes on the basis of overt, observable behavioral patterns, including (in the case of linguistic beings) patterns of linguistic behavior. The simple dispositionalist view is again just that there is nothing more to know about the attitudes: they are but dispositions to the observed behavioral patterns.

For many dispositionalists, the appeal of dispositionalism is precisely its superficial character. Our everyday practice of ascribing attitudes, so of explaining, predicting, and rationalizing one another and ourselves with reference to the attitudes, appears to be insensitive to whatever is going on, so to speak, under the hood. In fact, many think that the practice has remained more or less unchanged for millennia, even if there have been indefinitely many changes in views of what the mind is and where it is located, if it is has a location. In historical terms, it is only quite recently that we have suspected minds to be brains and their locations to therefore be the interior of the skull. Even still, facts about the brain, specified in cognitive neuroscientific or computational psychological terms, never enter everyday considerations when ascribing attitudes.

Indeed, if an alien being or some cognitively sophisticated descendent of existing non-human animals or some future AI were to seamlessly integrate into human (or post-human) society, forming what are to all appearances nuanced beliefs about, say, the shortcomings of the American constitution, where to invest next year, and how to appease the in-laws this holiday without compromising one’s values, then most of us would be at least strongly inclined to accept this being as a true believer, as really in possession of the attitudes they seem to have—any differences in their physical makeup notwithstanding (see Schwitzgebel 2013, as well as Sehon 1997 for similar examples). Dispositionalism accords well with this.

However, it does seem that one could have an attitude without any associated overt, observable behavioral dispositions—just as one might experience pain without exhibiting or even being disposed to exhibit any pain-related behavior (yelping, wincing, cursing, stamping about, crying, and so forth) (see Putnam 1963 on “super-spartans” or “super-stoics”). A locked-in patient, for example, has beliefs, though no ability to behaviorally exhibit them. (Incidentally, this highlights the implausibility of behaviorism as applied to the mental generally, not just to the attitudes.) If they have the relevant dispositions, this is only in a very attenuated sense.

In addition, it is not clear that the affective or phenomenological should be excluded. For example, if you believe that the earth is flat, might you not be disposed to, say, feel surprised when you see a picture of the earth from space? It is not clear why this should not be among the dispositions characteristic of your belief. What is more, it seems that one might have the associated behavioral dispositions without the attitude. A sycophant to a president, for example, might be disposed to behave as if she thought the president were good and wise, even if she believes the contrary.

Recognizing the force of these and related observations but appreciating the appeal of a superficial account of belief, other more liberal dispositionalists have allowed that the relevant dispositions may include not just dispositions to overt, observable behavior but also dispositions to cognition and affect. Despite his usual mischaracterization as a logical behaviorist, Gilbert Ryle (1949) is a prime example of a dispositionalist of this latter sort. Eric Schwitzgebel (2002, 2010, 2013) is an example of a contemporary theorist who adopts a view similar to Ryle’s.

Like Ryle, Schwitzgebel does not attempt to provide a reductive account. He allows that, when providing a dispositional specification of a particular attitude, we must inevitably make reference to other attitudes. In other words, he countenances the holism of the mental. His view is also like Ryle’s in that he allows that the relevant dispositions are not just dispositions to overt, observable behavior. Unlike Ryle, however, Schwitzgebel makes it a point to emphasize this aspect of his view. He also emphasizes the fact that, when we consider whether someone’s dispositional profile matches “the dispositional stereotype for believing that P”, “what respects and degrees of match are to count as “appropriate” will vary contextually and so must be left to the ascriber’s judgment”(2002, p. 253). He emphasizes, in other words, the vagueness and context-dependency of our ascriptions. Finally, also unlike Ryle, but in line with the dominant view at the beginning of the 21st century, Schwitzgebel is at least inclined to the view that attitudes are causes and belief-desire explanations thus causal explanations.

Combining dispositionalism and a causal picture of the attitudes poses some difficulties. On most views of dispositions developed in the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, dispositions must have categorical bases. Consider, for example, a new rubber band. It has the property of elasticity, and this is a dispositional property: it is disposed to stretch when pulled and to return to its prior shape when released. We can intelligibly ask why, and the answer will tell us something about the categorical basis of this property—something about the material constitution of the rubber band. Similarly, we explain the brittleness of glass and solubility of sugar in terms of their material constitutions (perhaps, a little more specifically, their microphysical structures). In the case of attitudes, construed as dispositions, the most plausible categorical bases would be states of the brain. Now the question arises whether we should identify these dispositions with their categorical bases or not. A dispositionalist attracted to the position for its superficial character is not likely to make this identification. (That attitudes are brain states would seem to be a deep view.) However, without this identification, more work would need to be done to explain how dispositions can be causes.

c. Computational-Representationalism

On the classical picture, described in Section 2a, to believe that the earth moves, Galileo must grasp the proposition that the earth moves in the way the belief suggests it—where, as discussed, the proposition is an abstract mind- and language-independent object with essential and absolute truth-conditions, residing somewhere in the so-called third realm (neither the physical nor the mental realms, but somewhere else altogether—Plato’s Heaven perhaps). As discussed, one trouble with this view is that, if an object is in neither time nor space, there is no clear sense in which it is anywhere, let alone an object. But even supposing we can make sense of this, it remains to explain how we can grasp this object, as well as the nature of the grasping relation. Frege and Russell are not of much help here.

Many philosophers—and Jerry Fodor is the primary architect here—essentially take the classical picture and psychologize it. Thus, the proposition grasped becomes a mental representation (expressing, meaning, or having this proposition as content)—the mental representation being a physical thing, literally located in one’s head—and the grasping relation becomes a functional role or, still more exactly, a computational role. That is, according to Fodor: if Galileo believes that the earth moves, there is in Galileo’s brain a mental representation that means that the earth moves and that plays the functional (or computational) role appropriate to belief. The details are complex (see the articles just linked to), but the basic idea is simple: it is in virtue of having a certain object moving around in your head in a certain way that you bear a certain relation to it and so may be said to have the attitude you have. So put, Fodor’s computational-representational view, unlike the dispositional views discussed above, is a deep view.

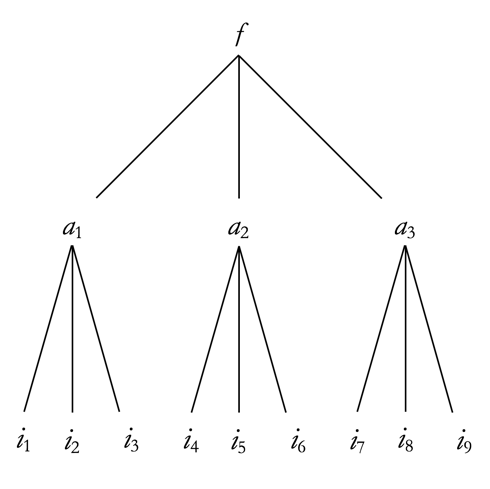

In the vocabulary of computational psychology, the object of an attitude is a computational data structure, over which attitude-appropriate computations are performed and so definable. At the level of description at which this structure is so identified, it is multiply-realizable, meaning here that algorithmic and implementation details may vary (Marr 1982). A schematic picture might help: Roughly, the top-level (the computational level) provides a formal specification of some function a mechanism might compute; the middle level (the algorithmic level) says how it is computed; and the bottom level (the implementation level) says how all this is physically realized in the brain. As depicted, there is more than one way to execute a function, and more than one way to physically realize its execution. In the end, the idea goes, we can account for the aspects of the mind thus theorized in purely physical terms (thus making the view another form of physicalism). Bridging these levels is not easy, but Fodor thinks that commonsense psychology can help in limning the computational structure of the mind-brain, or our cognitive architecture.

Roughly, the top-level (the computational level) provides a formal specification of some function a mechanism might compute; the middle level (the algorithmic level) says how it is computed; and the bottom level (the implementation level) says how all this is physically realized in the brain. As depicted, there is more than one way to execute a function, and more than one way to physically realize its execution. In the end, the idea goes, we can account for the aspects of the mind thus theorized in purely physical terms (thus making the view another form of physicalism). Bridging these levels is not easy, but Fodor thinks that commonsense psychology can help in limning the computational structure of the mind-brain, or our cognitive architecture.

On this view, again, the proposition of the classical view becomes a mental representation to which the subject stands in a particular attitude relation in virtue of the fact that the mental representation plays a certain computational role in the cognitive architecture of the subject: a belief-role or a desire-role, as the case may be. On Fodor’s view, since the content of this mental representation is propositional, and so is a proposition, the representation must have a linguistic form, that is, it must be syntactically structured—and thus, he reasons, a mental sentence, to wit, a sentence of Mentalese, our language of thought. Since he conceptualizes mental representations as objects, he speaks of their syntactic shapes (see, for example, his 1987). In fact, it is supposed to be in virtue of their shapes that mental representations and so the attitudes with which they are associated have causal powers—that is, the ability to make other things move, including the subject with the mental representation in her head.

Fodor (1987) thinks, in fact, that if you look at attitude reports and our practice of ascribing attitudes (in other words, at commonsense belief-desire psychology, or folk psychology), what you will find is that attitudes have at least the following essential properties: “(i) They are semantically evaluable. (ii) They have causal powers. (iii) The implicit generalizations of common-sense belief/desire psychology are largely true of them.” (p. 10).

As an example generalization of common-sense belief-desire psychology, Fodor (1987) provides the following:

If x wants that P, and x believes that not-P unless Q, and x believes that x can bring it about that Q, then (ceteris paribus) x tries to bring it about that Q. (p. 2)

Generalizations like this are implicit in that they need not be—and often are not—explicitly entertained or represented when they are used to explain and predict behavior with reference to beliefs and desires. Taking an example from Fodor (1978), consider the following instance of the above generalization: if John wants that it rain, and John believes that it will not rain unless he washes his car, and John believes that he can bring it about that he washes his car, then (ceteris paribus) John tries to bring it about that he washes his car. According to Fodor, such explanations are causal, and the attitude ascriptions involved individuate attitudes of a given type (belief, desire) by their contents (that it will not rain unless I wash my car, that it will rain). Moreover, such explanations are largely successful: the predictions pan out more often than not; and Fodor reasons, we therefore have grounds to think that these ascriptions are often true. If true, a scientific account of our cognitive architecture should accord with this.

These generalizations, moreover, are counterfactual-supporting: if a subject’s attitudes are different, we folk psychologists, equipped with these generalizations, will produce different predictions of their behavior. So, the generalizations have the characteristics of the laws that make up scientific theories. Granted, there are exceptions to the generalizations, and so exceptional circumstances. In other words, these generalizations hold ceteris paribus, that is, all else being equal. For example: if one wants it to rain, and believes that it will not rain unless one washes one’s car, and one believes that one can wash one’s car, then one will wash one’s car—unless it suddenly begins to rain, or one is immobilized by fear of the neighbor’s unleashed dog, or one suffers a seizure, and so forth. (As competent folk psychologists, we are very capable of recognizing the exceptions.) However, this does not mean that the generalizations or instances thereof are empty—that is, true unless false—argues Fodor (1987); for this would make the success of folk psychology miraculous. Besides, all the generalizations of the special sciences (that is, all the sciences but basic physics) have exceptions; and that is no obstacle to their having theories. So, in fact, Fodor thinks that folk psychology is or involves a bona fide theory—and that this theory is vindicated by the best cognitive science. As vindicated, the posits of folk psychology, namely beliefs, desires, and the rest, are therefore shown to be real. We return to this in Section 4.

As a bona fide theory, Fodor reasons that the referents of folk psychology’s theoretical terms are unobservable. Beliefs, desires, and the rest are therefore unobservables and thus inner as opposed to outer mental states. If the ascriptions are largely true, then—on a non-instrumentalist reading—what they refer to must exist and moreover have the properties the truth of the ascriptions requires them to have. The explanations in which these ascriptions figure are again causal, so these inner states must be causally efficacious. Since, according to Fodor (1987), “whatever has causal powers is ipso facto material” (p. x, Preface), it follows that mental states are physically realized (presumably, in the brain). Since, once more, they are individuated by their contents, they are content-bearing. Putting this together, then, the propositional attitudes are neurally-realized causally efficacious content-bearing internal states. As Fodor (1987) states the view:

For any organism O, and any attitude A toward the proposition P, there is a (‘computational’/‘functional’) relation R and a mental representation MP such that

MP means that P, and

O has A iff O bears R to MP. (p. 17)

Importantly, according to Fodor, computational-representationalism—unlike any other theoretical framework before it—allows us to explain precisely how mental states like propositional attitudes can have both contents and causal powers (so the first two essential properties noted above). Attitudes, indeed mental states more generally, do not just cause behaviors. They also causally interact with one another. For example, believing that if it rains, it will pour, and then coming to believe that it will rain (say, on the basis of a perceptual experience), will typically cause one to believe that it will pour. What is interesting about this is that this causal pattern mirrors certain content-relations: If “it pours, if it rains” and “it rains” are true, “it pours” is true. This fact may be captured formally or syntactically: P → Q, P ⊢ Q. (This indicates that Q is derivable or provable from P → Q and P. This common inference pattern is known as Modus Ponens. See the article on propositional logic.) This, in turn, permits us to build machines—computers—which exhibit this causal-inferential behavior. In fact, not only may computer programs model our cognitive processes, we also are, on this view, computers of a sort ourselves.

Among those who accept the computational-representational account of propositional attitudes, some deny that the relevant representations are sentences, and some maintain agnosticism on this question (see, for example, Fred Dretske, Tyler Burge, Ruth Millikan). Moreover, not everyone who accepts that they are sentences accepts that they are sentences of a language of thought distinct from any public language (Harman 1973). Still others deny that only language is compositional—arguing, for example, that maps, too, can be compositional (see Braddon-Mitchell and Jackson 1996, Camp 2007). Views also differ on how the relevant mental representations get their content (see the article on conceptual role semantics, as well as the article on Fodor, for some of the views in this area). In any case, Fodor’s view has been the most influential articulation, and the above theoretical identification is general enough to be accepted by any computational-representationalist.

3. Propositions, Propositional Attitude Reports, and the Method of Truth in Metaphysics

Theorizing about propositions, propositional attitudes, and propositional attitude reports have traditionally gone together. The connection is what Davidson (1977) called “the method of truth in metaphysics”, or what Robert Matthews (2007) calls the “reading off method”—that is, the method of reading off the metaphysics of the things we talk about from the sentences we use to talk about these things, provided that the logical form and interpretation of the sentences have been settled. This section discusses this method and the metaphysics of propositional attitudes and propositions arrived at by its application.

a. Reading Off the Metaphysics of Propositional Attitudes

Many valid natural language inferences involving propositional attitude reports seem to require that these reports have relational logical forms—the reports thereby reporting the obtaining of a relation between subjects and certain objects to which we seem to be ontologically committed by existential generalization:

| Galileo believes that the earth moves. | Bgp |

| ∴ Galileo believes something. | ∴ ∃xBgx |

(Ontology is the study of what there is. One’s ontological commitments are thus what one must take to exist. This notion of ontological commitment is most famously associated with Quine (1948, 1960); as he put it: “to be is to be the value of a bound variable”.) That is, if a report like

(1) Galileo believes that the earth moves.

has the logical form displayed above, then if Galileo believes that the earth moves, there is something—read: some thing, some object—Galileo believes, to wit, the proposition that the earth moves. If you believe that Galileo believes this, you are committed to the existence of this object.

Some of these inferences, moreover, appear to require that the objects to which subjects are related by such reports are truth-evaluable:

| Galileo believes that the earth moves. | Bgp |

| That the earth moves is true. | Tp |

| ∴ Galileo believes something true. | ∴ ∃x(Bgx & Tx) |

If Galileo’s belief is true, then the proposition that the earth moves is true. We thus say that the object of Galileo’s belief, the proposition, is also the content of the belief. Still other inferences appear to require that attitudes are shareable:

| Galileo believes that the earth moves. | Bgp |

| Sara believes that the earth moves. | Bsp |

| ∴ There is something they both believe. | ∴ ∃x(Bgx & Bsx) |

On the classical view owing to Frege and Russell (see Section 2a), objects and contents of belief, truth-evaluable, and shareable, not to mention the referents of that-clauses (for example “that the earth moves”) and expressible by sentences (for example “the earth moves”), are among the specs for propositions. Thus, a report like (1) appears to be true just in case Galileo stands in the belief-relation to the proposition that the earth moves, the subject and object being respectively the referents of “Galileo” and “that the earth moves”.

Of course, it is not just beliefs that we report. We also report fears and hopes and many other attitudes besides. For example:

(2) Bellarmine fears that the earth moves.

(3) Pia hopes that the earth moves.

So, we see that various attitudes may have the same proposition as their object (and content). Of course, the same type of attitude can be taken towards different propositions, referred to with different that-clauses (for example “that the earth is at the center of the universe”). Generalizing on these data, we therefore seem to be in a position to say the following:

Instances of x V that S are true if and only if x bears the relation expressed by V (the V-relation) to the referent of that S.

with (1)–(3) being instances of this schema.

This analysis is typically extended also to reports of speech acts of various kinds, which are sometimes included under the label propositional attitudes (Richard 2006). For example:

(4) Galileo {said/asserted/proclaimed/hypothesized…} that the earth moves.

In fact, replacing the attitude verb with a verb of saying, inferences like the following appear to be equally valid:

| Galileo said that the earth moves. | Sgp |

| ∴ Galileo said something. | ∴ ∃xSgx |

| Galileo said that the earth moves. | Sgp |

| That the earth moves is true. | Tp |

| ∴ Galileo said something true. | ∴ ∃x(Sgx & Tx) |

| Galileo said that the earth moves. | Sgp |

| Sara said that the earth moves. | Ssp |

| ∴ There is something they both said. | ∴ ∃x(Sgx & Ssx) |

As one can believe what is said (asserted, proclaimed, and so forth), inferences like the following likewise appear valid:

| Sara believes everything that Galileo says. | ∀x(Sgx ⊃ Bsx) |

| Galileo said that the earth moves. | Sgp |

| ∴ Sara believes that the earth moves. | ∴ Bsp |

The objects of these reports are again often thought to be propositions. These inferences thereby lend further support for the above view of the form and interpretation of reports. This view, what Stephen Schiffer (2003) calls the Face-Value Theory, has long been the received view.

b. Reading Off the Metaphysics of Propositions

One remaining question concerns the nature of these propositions, taken to be the objects and contents of the attitudes. Getting clear on this would seem crucial to getting clear on what the propositional attitudes are, if they are indeed attitudes taken towards propositions. To this end, the same method has been used.

Provided that that-clauses like “that the earth moves” are replaced by individual constants in the logical translations of reports like (1)–(4), it seems right to construe that-clauses as singular referring terms (similar to proper names) and so their referents—propositions, by the foregoing reasoning—as objects. Moreover, if it is another property of propositions to be expressed by (indicative, declarative) sentences, then provided that these sentences have parts which compose in systematic ways to form wholes, it seems natural to think that the propositions are likewise structured—with the parts of the propositions corresponding to the parts of the sentences. So, propositions are structured objects, though distinct from the sentences used to express them. Moreover, since they are shareable, even countenancing vast spatiotemporal separation between subjects (both we and Galileo can believe that the earth moves), they must be, it is reasonable to think, abstract and mind-independent. Or so Frege (1918) reasoned.

With this granted, we might then ask what the nature of the constituents of propositions is. If, for example, when we use a sentence like

(5) The earth moves.

we refer to the earth and ascribe to it the property of moving, and we express propositions with sentences, then it is natural to think that the constituents of propositions are objects, like the earth, and properties (and relations), like the property of moving. This is the so-called Russellian view of the constituents of propositions, after Russell.

If the propositional contribution of a term just is a certain object, namely the one to which the term refers, then any other term that refers to the same object will have the same propositional contribution. This seems to mirror an observation made concerning sentences like (5). If, for example, “the earth” and “Ertha” are co-referring, then if (5) is true, so is

(6) Ertha moves.

That is, if

(7) The earth is Ertha.

is true, then—holding constant the sentences in which these terms are embedded—the one term should be substitutable for the other without change in truth value of the embedding sentence. The terms are, as it is sometimes put, intersubstitutable salva veritate (saving truth).

This seems, however, not to hold generally, as Frege (1892) famously observed. For suppose that Galileo believes that the earth and Ertha are distinct. Then even if the earth is Ertha and Galileo believes that the earth moves,

(8) Galileo believes that Ertha moves.

is false, or so it might seem. (Some Russellians deny this; see, for example, Salmon 1986.) Such apparent substitution failures are widely known as Frege cases. Frege thought that they cast doubt on the Russellian view of propositional constituents. For if propositional attitudes are relations between subjects and propositions, he reasoned, then provided that the type of attitude ascribed to Galileo is the same (belief, in the running example), there must be a difference in the proposition which accounts for the difference in the truth value of these reports.

Frege cases are related to another puzzle discussed by Frege (1892), widely known as the puzzle of cognitive significance. To take a widely used example from Frege, while the Babylonians would have found

(9) Hesperus is Hesperus.

and

(10) Phosphorus is Phosphorus.

as trivial as anyone else, it would have come as a surprise to them that

(11) Hesperus is Phosphorus.

Establishing the truth of (11) was a non-trivial astronomical discovery. It turns out, contrary to what the Babylonians believed, that Hesperus, the heavenly body which shines in the evening, and Phosphorus, the heavenly body which shines in the morning, are one and the same—not distinct stars, as the Babylonians believed, but the planet Venus. Yet, if (11) is true, and “Hesperus” and “Phosphorus” are two names for one and the same object, there is a sense in which (9), (10), and (11) all say the same thing. Therefore, an explanation of the fact that (9) and (10) are trivial while (11) is cognitively significant seems to be owed.

One possible explanation for the difference in cognitive significance is that we may attach distinct senses to distinct expressions, even if they are co-referring. If propositions are what we grasp when we understand sentences, then perhaps, Frege hypothesized, propositional constituents are not individuals and relations but senses. This is the so-called Fregean view of propositions.

In the first instance, senses are whatever difference accounts for the difference in cognitive significance between (9) and (10), on the one hand, and (11) on the other. More exactly, Frege suggested that we think of senses as ways of thinking about or modes of presenting what we are talking about which are associated with the expressions we use. For example, the sense associated with “Hesperus” by the Babylonians could be at least roughly captured with the description “the star that shines in the evening” and the sense associated with “Phosphorus” by the Babylonians could be at least roughly captured with the description “the star that shines in the morning”. (For further discussion, see the articles on Frege’s philosophy of language and Frege’s Problem.)

Taking this idea on board, compatibly with accepting the idea that co-referring terms are intersubstitutable salva veritate, Frege suggested that we might then account for substitution data like the above by a systematic shift in the referents of the expressions embedded in the scope of an attitude verb like “to believe”—in particular, a shift from customary referent to sense. On this view, for example, the referent of “Hesperus”, when embedded in

(12) Bab believes that Hesperus shines in the morning.

is not Hesperus (that is, Venus) but the sense of “Hesperus”. Similarly, the semantic contribution of the predicate “shines in the morning” would be the sense of that expression, not the property of shining in the morning. Putting these senses together, we have the proposition (or thought) expressed by “Hesperus shines in the morning”, the referent of the that-clause “that Hesperus shines in the morning”. This way we can see how (12) and

(13) Bab believes that Phosphorus shines in the morning.

may have opposite truth values, even if (11) is true.

Employing his theory of descriptions, Russell (1905) offered a different solution which is compatible with accepting the Russellian view of propositions. Still other solutions have been proposed, motivated by a variety of Frege cases. Common to almost all positions in this literature is the assumption that attitudes are relations between subjects and certain objects. Not all of the proposed solutions, however, take propositions to be structured objects (see, for example, Stalnaker 1984). In fact, not all of the proposed solutions take the objects to be propositions. Some instead propose different proposition-like objects, including: natural language sentences, mental sentences, interpreted logical forms, and interpreted utterance forms (see, for example, Carnap 1947, Fodor 1975, Larson and Ludlow 1993, and Matthews 2007). On such views, the expression “propositional attitudes” turns out to be something of a misnomer, as they are not, strictly speaking, attitudes toward propositions.

c. A Challenge to the Received View of the Logical Form of Attitude Reports

It should be noted that the received view of the logical form of propositional attitude reports discussed in Section 3a has not gone unchallenged. Much recent work in this area has been motivated by a renewed attention to a puzzle known as Prior’s Substitution Puzzle (after Arthur Prior, who is often credited with introducing the puzzle in his 1971 book).

If “that the earth moves” refers to the proposition that the earth moves, then assuming (as is common) that co-referring terms are intersubstitutable salva veritate, we should expect that substituting “that the earth moves” for “the proposition that the earth moves” in (2) will not change the sentence’s truth value. But here is the result:

(14) Bellarmine fears the proposition that the earth moves.

It seems clear that one may fear that the earth moves without fearing any propositions. We could give up the commonly held substitution principle, but this would be a last resort.

A natural thought is that the problem is peculiar to fear, but the problem is seen with many other attitudes besides. Take (3), for example, and perform the substitution. The result:

(15) Sara hopes the proposition that Galileo is right.

Clearly, something has gone wrong; for (15) is not even grammatical.

At this point, one might begin to question whether propositions are in fact the objects of the attitudes. However, it appears that none of the available alternatives to propositions will do:

Bellarmine fears the {proposition/(mental) sentence/interpreted logical form…} that the earth moves.

Some proponents of the received view of the logical form of attitude reports have provided responses to this problem which are compatible with maintaining the received view (see, for example, King 2002, Schiffer 2003). Others argue that the received view must be abandoned, and on some of these alternative views, that-clauses are not singular referring terms but predicates (see, for example, Moltmann 2017).

Insofar as one accepts the reading off method, different views of the logical form of attitude reports may lead to different views of the metaphysics of the propositional attitudes. Of course, not everyone accepts this method. For some general challenges to the method, see, for example, Chomsky (1981, 1992), and for challenges to the method specifically as it applies to theorizing about propositional attitudes, see, for example, Matthews 2007.

4. Folk Psychology and the Realism/Eliminativism Debate

This section discusses how propositional attitudes figure in folk psychology and how the success or lack of success of folk psychology has figured in debates about the reality of propositional attitudes.

a. Folk Psychology as a Theory (Theory-Theory)

The term “folk psychology” is sometimes used to refer to our everyday practice of explaining, predicting, and rationalizing one another and ourselves as minded agents in terms of the attitudes (and other mental constructs, such as sensations, moods, and so forth). Sometimes, it is more specifically used to refer to a particular understanding of this practice, according to which this practice deploys a theory, also referred to (somewhat confusingly) as “folk psychology”. This theory about the practice of folk psychology is sometimes referred to as the Theory-Theory (TT). Wilfrid Sellars (1956) is often credited with providing the first articulation of TT, and Adam Morton (1980) with coining the term.

The idea that folk psychology deploys a theory immediately raises the question of what a theory is. At the time TT was introduced, the dominant view of scientific theories in the philosophy of science was that theories are bodies of laws, that is, sets of counterfactual-supporting generalizations (see Section 2c), generally codifiable in the form:

If___, then ___.

Where the first blank is filled by a description of antecedent conditions, and the second blank is filled by a description of consequent conditions. If the law is true, then if the described antecedent conditions obtain, the described consequent conditions will obtain. Thus, the law issues in a prediction and thereby gives us an explanation of the conditions described in its consequent—to wit, a causal explanation, the one condition (event, state of affairs) being the cause of the other.

This idea in turn raises the question of what the laws of folk psychology, understood as a theory (FP, for short), are supposed to be. The following example was provided in Section 2c:

If x wants that P, and x believes that not-P unless Q, and x believes that x can bring it about that Q, then (ceteris paribus) x tries to bring it about that Q.

And another example is the following (see Carruthers 1996):

If x has formed an intention to bring it about that P when R, and x believes that R, x will act so as to bring it about that P.

Additional laws take a similar form. It is acknowledged that they all admit of exceptions; but this, it is argued, does not undermine their status as laws: after all, all the laws of the special sciences have exceptions (again, see discussion in 2c).

Given our competence as folk psychologists, one might expect many more laws like this to be easily formalizable. Perhaps surprisingly, however, only a few more putative laws of FP have ever been presented (but see Porot and Mandelbaum 2021 for a report on some recent progress). Considering how rich and sophisticated folk psychology is (we are, after all, remarkably complex beings), one would expect FP to be a very detailed theory. As a result, one might think that the relative dearth of explicitly articulated laws might cast doubt on the idea that folk psychology in fact employs a theory. The line that proponents of folk psychology as a theory (FP) take is that the laws are implicitly or tacitly known and need not be explicitly entertained or represented when deploying the theory. This position is not an ad hoc one, since many domains in the cognitive sciences take a similar view—for example, in Chomskyan linguistics, which aims to provide an explicit articulation of natural language grammars. We are all competent speakers of a natural language and so must have mastered the grammar of this language. Manifestly, however, it is quite another thing to have an explicitly articulated grammar of the language in hand. We speak and comprehend our natural languages effortlessly, but coming up with an adequate grammar is devilishly difficult. The same may be true when it comes to our competence as folk psychologists.

It is generally agreed that the core of FP would comprise those laws concerning the attitudes (including, for example, the above laws). The key terms of the theory—its theoretical terms—would thus include “belief”, “desire”, “hope”, “fear”, and so forth, or their cognates. If FP is indeed a successful theory, and this is not a miraculous coincidence, then we have reason to think that its theoretical terms succeed in referring—that is, we have reason to think that there are beliefs, desires, hopes, fears, and the rest. If, however, FP is not a successful theory, then the attitudes may have to go the way of the luminiferous aether, phlogiston, and other theoretical posits of abandoned theories.

This understanding of folk psychology and the stakes at hand provide the shared background to the realism/eliminativism debate.

b. Realism vs. Eliminativism

The realist position is represented most forcefully and influentially by Fodor (whose position is described in Section 2c). Fodor takes the success of FP, considered independently of the cognitive sciences, to be obvious. Here is a typical passage from his (1987) book:

Commonsense psychology works so well it disappears… Someone I don’t know phones me at my office in New York from—as it might be—Arizona. ‘Would you like to lecture here next Tuesday?’ are the words that he utters. ‘Yes, thank you. I’ll be at your airport on the 3 p.m. flight’ are the words that I reply. That’s all that happens, but it’s more than enough; the rest of the burden of predicting behavior—of bridging the gap between utterances and actions—is routinely taken up by theory. And the theory works so well that several days later (or weeks later, or months later, or years later; you can vary the example to taste) and several thousand miles away, there I am at the airport, and there he is to meet me. Or if I don’t turn up, it’s less likely that the theory has failed than that something went wrong with the airline. It’s not possible to say, in quantitative terms, just how successfully commonsense psychology allows us to coordinate our behaviors. But I have the impression that we manage pretty well with one another; often rather better than we cope with less complex machines. (p. 3)

In fact, he adds: “If we could do that well with predicting the weather, no one would ever get his feet wet; and yet the etiology of the weather must surely be child’s play compared with the causes of behavior.” (p. 4)

What is more, he argues, signs are that the cognitive sciences—computational psychology, in particular—will vindicate FP by giving its theoretical posits pride of place (see also Fodor 1975). Eliminativists, of course, have a very different view.

Perhaps the most widely discussed and influential argument, or set of arguments, against the realist position and in favor of eliminativism is set forth by Paul Churchland in his (1981) essay “Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes.” There, the eliminativist thesis is stated as follows:

Eliminative Materialism is the thesis that our commonsense conception of psychological phenomena constitutes a radically false theory, a theory so fundamentally defective that both the principles and the ontology of that theory will eventually be displaced, rather than smoothly reduced, by completed neuroscience. (p. 67)

He continues:

Our mutual understanding and even our introspection may then be reconstituted within the conceptual framework of completed neuroscience, a theory we may expect to be more powerful by far than the common-sense psychology it displaces, and more substantially integrated within physical science generally. (ibid.)

Churchland argues not only that FP will be shown to be false, but that it will be eliminated—that is, replaced by a more exact and encompassing theory, in terms of which we may then reconceptualize ourselves.

Whereas Churchland welcomes the prospect, Fodor (1990) has this to say:

If it isn’t literally true that my wanting is causally responsible for my reaching, and my itching is causally responsible for my scratching, and my believing is causally responsible for my saying… If none of that is literally true, then practically everything I believe about anything is false and it’s the end of the world. (p. 156)

This might strike some as hyperbolic at first. However, even the eliminativist thesis seems to presuppose what it denies; for after all, is not the assertion of the thesis an expression of belief? So, does Churchland not have to believe that there are no beliefs? (See Baker 1987)

Churchland offers three main arguments for his eliminative view. The first is that FP does not explain a wide range of mental phenomena, including “the nature and dynamics of mental illness, the faculty of creative imagination…the nature and psychological function of sleep…the rich variety of perceptual illusions” (1981, p. 73), and so on. The second is that, unlike other theories, folk psychology seems resistant to change, has not shown any development, is “stagnant”. The third is that the kinds of folk psychology (belief, desire, and so on) show no promise of reducing to, or being identified with, the kinds of cognitive science—indeed, no promise of cohering with theories in the physical sciences more generally.

A number of responses have been provided by those who take FP to be a successful theory. Regarding the first argument, one might simply reply that the theory is successful when applied to phenomena within its explanatory scope. FP needs not be the theory of everything mental. Regarding the second, one might observe that a remarkably successful theory does not call for revision. The third argument is the strongest. However, at the beginning of the 21st century (and all the more so, then, in the last decades of the 20th century, when this debate was an especially hot topic) it turns on little more than an empirical bet, about which there can be reasonable disagreement. Many theorists who appeal to the cognitive sciences in advancing eliminativism appeal in particular to developments in the connectionist paradigm or to other developments in lower-level computational neuroscience (see, besides Churchland 1981, Churchland 1986, Stich 1983, Ramsey et al. 1990), the empirical adequacy of which has been a subject of debate—particularly when it comes to explaining higher-level mental capacities, such as the capacities to produce and comprehend language, which are centrally implicated in folk psychology. (For more on this, see the article on the language of thought.)

There are many other responses to eliminativist arguments besides these, including some which involve rejecting TT (see Section 4c). If folk psychology does not involve a theory, then it cannot involve a false theory; and by the same token, then, beliefs, desires, and the rest cannot be written off as empty posits of a false theory. Even among those who accept that folk psychology involves a theory though, some might reject the idea that the falsity of the theory (namely, FP) entails the nonexistence of beliefs, desires, and the rest.

Stich (1996), a one-time prominent eliminativist, came then to suggest (following Lycan 1988) that the general form of the eliminativist argument—

(1) Attitudes are posits of a theory, namely FP;

(2) FP is defective;

(3) So, attitudes do not exist.

—is enthymematic, if it is not invalid. The suppressed premise Stich identifies is an assumption about the nature of theoretical terms, according to which their meanings are fixed by their relations with other theoretical terms in the theory in which they are embedded (see Lewis 1970, 1972). In other words, a form of descriptivism, according to which the meanings of terms are fixed by associated descriptions, is assumed. On this view, for example, the meaning of “water” is fixed by such descriptions as that “water falls from the sky, fills lakes and oceans, is odorless, colorless, potable, and so forth”. Water, in other words, just is whatever uniquely satisfies these descriptions. Similarly, then, beliefs would be those mental states which are, say, semantically evaluable, have causal powers, a mind-to-world direction-of-fit, and so forth—or in brief, those states of which the laws of FP featuring the term “belief” or its cognates are true. If it turns out that nothing satisfies the relevant descriptions, there are no beliefs. This works the same for desires and the rest. However, one might well reject descriptivism and so block this implication. In fact, the dominant view at the beginning of the 21st century in the theory of reference is not descriptivism but the causal-historical theory of reference.

According to the causal-historical theory of reference (owing principally to the work of Saul Kripke and Hilary Putnam), the referent of a term is fixed by an original baptism (typically involving a causal connection to the referent), later uses of the term depending for their referential success on being linked to other successful uses of the term linking back to the original baptism. Such a view allows for the possibility that we can succeed in referring to things even when we have very mistaken views about them, as it in fact seems possible to many. For example, it seems right that the ancients succeeded in referring to the stars, despite having very mistaken views about what they are. Similarly, then, the idea goes, if the causal-historical theory is correct, it should be possible that we succeed in referring to propositional attitudes even if we have very mistaken views about their nature, so even if FP is defective.

But in fact, Stich’s (1996) skepticism about the eliminativist argument goes even deeper than this, extending to the very method of truth or reading off method in metaphysics (what Stich calls “the strategy of semantic ascent”). It is not clear, he argues, what is required of a theory of reference, or whether there might be such a thing as the correct theory of reference. After all, descriptivism might seem to better accord with cases where we do reject the posits of rejected theories—the luminiferous aether, phlogiston, and so on.

One idea might be to have a close look at historical cases where theoretical posits have been retained despite theory change and cases where theory change leads to a change in ontology and see if we can uncover implicit general principles for deciding between (a) “we were mistaken about Xs” and (b) “Xs do not exist”. But Stich (1996) despairs of the prospects:

It is entirely possible that there simply are no normative principles of ontological reasoning to be found, or at least none that are strong enough and comprehensive enough to specify what we should conclude if the [premises] of the eliminativist’s arguments are true. (p. 66-7)

Moreover, he continues:

In some cases it might turn out that the outcome was heavily influenced by the personalities of the people involved or by social and political factors in the relevant scientific community or in the wider society in which the scientific community is embedded. (p. 67)

If this is correct, then it is indeterminate whether there are propositional attitudes, and it will remain indeterminate “until the political negotiations that are central to the decision have been resolved” (ibid., p. 72).

This gives us a very different view of the stakes at hand, as the reality of the attitudes no longer appears to be a question of what is the case independently of human interests and purposes. The question is, as Stich puts it, political. But this view, which is a sort of social constructivism, is controversial—even if some of the main lines of thought leading to this view have less controversial roots in pragmatism.

c. Alternatives to Theory-Theory

As noted in Section 4b, not every theorist of folk psychology accepts TT. One of the main alternatives to TT, which was developed against the backdrop of the realism/eliminativism debate, is the simulation theory (ST). According to this view, we do not deploy a theory in explaining, predicting, and rationalizing one another (that is, in brief, in practicing folk psychology). Instead, what we do is to simulate the mental states of others, put ourselves in their mental shoes, or take on their perspective (Heal 1986, Gordon 1986, Goldman 1989, 1993, 2006). Different theorists spell out the details differently, but there is a common core, helpfully summarized by Weiskopf and Adams (2015):

In trying to decide what someone thinks, we imaginatively generate perceptual inputs corresponding to what we think their own perceptual situation is like. That is, we try to imagine how the world looks from their perspective. Then we run our attitude-generating mechanisms offline, quarantining the results in a mental workspace the contents of which are treated as if they belonged to our target. These attitudes are used to generate further intentions, which can then be treated as predictions of what the target will do in these circumstances. Finally, explaining observed actions can be treated as a sort of analysis-by-synthesis process in which we seek to imagine the right sorts of input conditions that would lead to attitudes which, in turn, produce the behavior in question. These are then hypothesized to be the explanation of the target’s action. (p. 227)

One perceived advantage of this view, insofar as folk psychology is thought not to involve a theory, is that the attitudes (and other mental constructs) appear to be immune to elimination. Of course, just what folk psychology is or involves is itself an empirical question, and in particular a question for psychology. For a sustained empirical defense of ST, pointing to paired deficits and neuroimaging, among other lines of evidence, see Goldman 2006.